(Virtual Motor City)

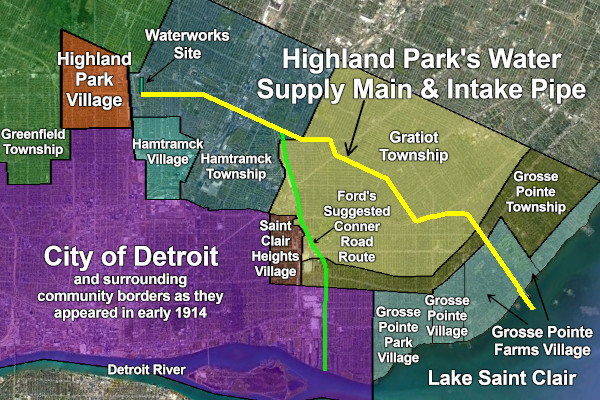

The City of Highland Park once operated its own independent municipal water supply, from June 1915 through December 2012. Toward the end of that period, while the city was under emergency state financial oversight, inspections had found that the facility had suffered from years of deferred maintenance and was therefore "temporarily" shut down as a precautionary measure. Switching the city over to Detroit's water system has resulted in an ongoing logistical, legal and financial nightmare, with residents of Michigan's poorest city receiving questionable water bills, some totaling thousands of dollars. In a recent setback, Highland Park was ordered to pay $21 million in unpaid water and sewerage bills by a Michigan appellate court in August 2021.

This situation has given rise to certain questions. Would this have happened if Highland Park never built a separate water facility? Why exactly did the city want an independent waterworks to begin with? Answering these questions may shed some light on the position Highland Park finds itself in today.

How Highland Park Obtained its Own Water

Highland Park's shuttered water treatment facility in 2022.

Highland Park first began receiving Detroit municipal water back in 1897, when it was still just a village. The village council had paid Detroit' Board of Water Commissioners to lay water mains in the streets and then supply the village with water at 6 cents per 1,000 gallons—the normal rate for outside villages at the time, which was double the amount Detroit residents paid. Detroit placed a water meter at the city border and charged Highland Park as a customer; village was responsible for billing individual customers.

This arrangement appeared to be satisfactory to everyone until around 1913, when complaints of low water pressure began to mount. The village council hired an experienced hydraulic engineer who happened to live in Highland Park to consult on the feasibility of building an independent waterworks. In October 1913 the engineer reported that such a project was indeed possible, and should even provide cheaper water. The village also approached Detroit the following month to see if the city could simply supply additional water pressure. However, Detroit claimed that this could not be done, pointing out that western parts of Detroit had it even worse than Highland Park.

The village administration decided to ask voters to approve of the $450,000 waterworks project, to be financed by issuing interest-bearing municipal bonds. Although most voters approved (440 votes in favor, 378 against), a 60% majority was required, so the proposition failed.

Increasing Pressure

What was the cause of the low water pressure? It should noted that factories in and around Highland Park were all drawing from Detroit's municipal water system at the time. Industries consumed water largely for generating steam to power their factories. The Ford Motor Company was both the largest automaker and water consumer, its demands were continually growing. Globally, Ford produced about 35,000 vehicles in 1911 and 69,000 in 1912. By the end of 1913, the company would manufacture more than 170,000 vehicles—mere drops in the bucket compared to what was coming. If Ford was going to continue to grow, it was going to get more water one way or another.

Two months after the first waterworks bond failed, the village council placed basically the same proposal on the ballot again, for the January 24, 1914 election. The Ford Motor Company did not stand idly by this time, but was actively engaged in garnering support for the project, as seen in the following article from the January 17, 1914 edition of the Detroit Free Press:

FORD FAVORS WATER PLANT IN HIGHLAND PARK

Auto Manufacturer Asks His Employes to Vote in Favor of Bond Issue.

Henry Ford favors the proposed installation of a waterworks for Highland Park, and will lend his aid in the efforts of the villagers to carry the bond proposition at the special election, January 24.

The motor car manufacturer made public his views on the question, which is the subject of bitter contest in the village, when he issued a statement to the business men of Highland Park Friday morning, Mr. Ford told the business men that he would ask his employes to vote for the proposition, and that he thought about 400 votes would be gathered from his plant.

The action of Mr. Ford, it is believed by supporters of the proposed waterworks, will tend to influence the rest of the village in its vote on the question.

("Ford favors water plant in Highland Park." Detroit Free Press, Jan. 17, 1914.)

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

The company's CEO even wrote a personal letter of support to Highland Park Village President Donald Thomson:

Mr. Donald Thompson: [sic]

I take this opportunity of expressing my appreciation of the efforts of the village council to procure an adequate supply of water for Highland Park. In my opinion, the establishment of an independent waterworks that will furnish an abundance of good pure water direct from Lake St. Clair for domestic and manufacturing purposes will be a great thing for Highland Park now, and in its future growth and development.

Wishing you success, I am,

Yours truly,

HENRY FORD

("Propose $450,000 water bond issue." Detroit Free Press, Jan. 18, 1914.)

Village President Thomson was an ardent supporter of the waterworks project. "Highland Park is suffering from a shortage of water throughout the year, and especially in hot weather," Thomson said, as quoted in the Free Press. "Water pressure in our village is so low that it is frequently impossible to get water in the second story. What has done more than anything to awaken our people, however, is the fact that recently complaints from various quarters as to water shortage were more and more frequent. Among those complaining are such large users of water as the Ford Motor company, the Maxwell Motor company and the Gray Motor company." ("Predicts victory of water project." DFP, Jan. 23, 1914.)

More than 70% of voters (1,151 to 442) approved the bond issue at the election on January 24, 1914. But the Ford Motor Company's role was not over. The corporation's secretary-treasurer, Frank L. Klingensmith, and attorney, Alfred Lucking, met several times with Detroit Mayor Oscar Marx after the city offered to extend an additional water main to the village after all, in May 1914. The Free Press reported, "Mr. Klingensmith would not state whether [Detroit's offer] will end the squabble. The Ford Motor company is hard hit by the present lack of water pressure." ("Detroit offers to extend main to Highland Park." Detroit Free Press, May 30, 1914.) Detroit was evidently unable to ensure enough water, as Highland Park continued to pursue its own supply. Ford officials were at it again when Grosse Pointe Farms was attempting to block the construction of a pumphouse on the shore of Lake Saint Clair. Klingensmith and Lucking tried to circumvent the Board of Water Commissioners by getting permission from the city council committee on streets to lay pipe down an alternate route along Conner Avenue, but the plan failed. ("Solon blocks Highland Park's water scheme." The Detroit Times, Jun. 9, 1914.)

After many delays and an additional $40,000 appropriation to finish the job, the waterworks was officially put into operation on June 28, 1915. Technically, this system was never 100% independent of Detroit's. Emergency connections have always remained in place, which have been opened in the past when Highland Park experienced unexpected drops in water pressure. (Unfortunately, it appears that the city's water pipes have been supplied solely through these emergency connections since 2012 according to the Highland Park Human Rights Coalition, resulting in hazardously low water pressure.)

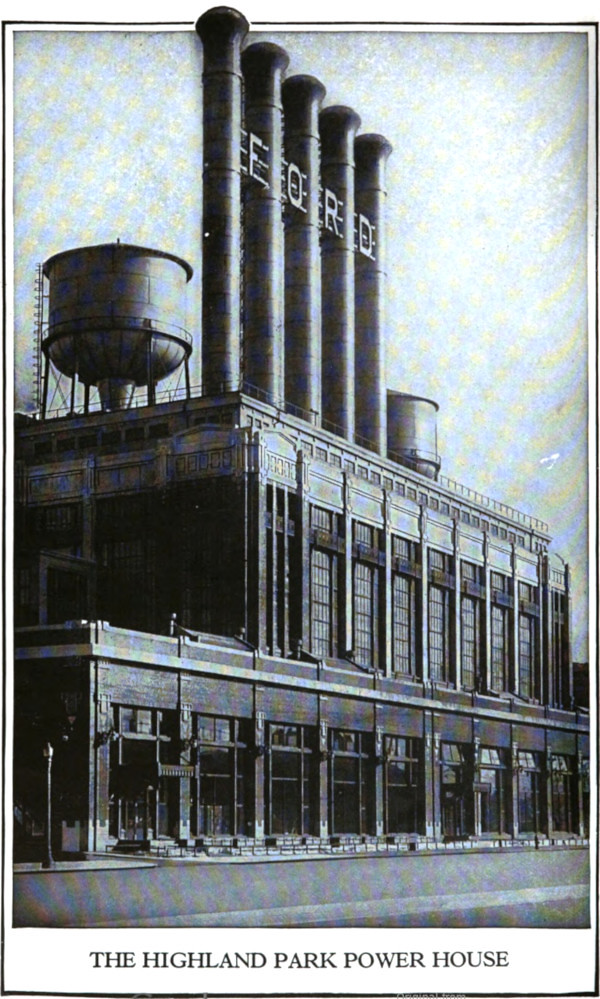

Just 35 days into service, Highland Park City Engineer Lawrence Whitsit reported that the brand new 13,000,000 gallon-per-day waterworks was already insufficient. He cited two reasons: 1) the system was temporarily servicing some Detroit water customers just north of the village; and 2) the Ford Motor Company was building a new powerhouse which just by itself would require more than twice the entire waterworks' maximum output. ("Highland Park's new water works is not adequate." Detroit Free Press, Aug. 3, 1915.) The Detroit Free Press reported:

Highland Park must increase the capacity of its water plant almost four fold in order to provide the future demands of the Ford Motor company.

Frank L. Klingensmith, secretary of the Ford company, has told the village officials that in the near future the Ford factory will need approximately 30,000,000 gallons of water daily. The present daily capacity of the village water works is approximately 13,000,000 gallons.

According to Don Thomson, Highland Park president, the Ford company's wants for water in the future can readily be supplied, Mr. Thomson said Tuesday.

"We intend to increase the size of the water works equipment to a capacity of 50,000,000 gallons daily. This will provide 20,000,000 gallons for other consumption and ample protection of the village from fire."

("Requires greater supply of water." Jan. 26, 1916)

(Hathi Trust)

Completed in 1916, the Ford Motor Company's powerhouse was an engineering wonder. Consuming 30 tons of coal per hour, it produced up to 60,000 horse power, making it possibly the largest generator of direct current in the world at the time. According to the company, the facility had the capacity to power a city of 500,000 people.

Interior view of the Ford's powerhouse and its massive gas-steam engines.

(Image via Facebook, originally from Facts from Ford (1920).)

Highland Park had some time to catch up while construction progressed on the powerhouse. The village hired engineers from the University of Michigan to draw up plans for a vastly improved system. This involved building a filtration plant, converting the old 2 million gallon reservoir into a covered coagulation basin, and constructing a new 45 million gallon reinforced concrete reservoir, believed then to be the largest structure of its kind in the western hemisphere. Voters approved taking on an additional $450,000 in bonded debt for the undertaking on July 10, 1916. The reservoir was put into use on April 4, 1918, coincidentally the same day that Highland Park became a city. The filtration plant, delayed by World War I, finally had a "soft opening" on November 13, 1920, followed by a formal dedication on December 4.

Highland Park's 45-million-gallon reservoir circa 1920.

(Virtual Motor City)

The Ford Motor Company's output took off after 1920, and the Highland Park Waterworks was one essential part of making that happen. In May 1921, the company produced its five millionth Model T, thirteen years into production. In just six more years, the company would produce another 10 million. Final assembly occurred in Ford factories around the world, but most essential components (engines, chassis, etc.) were manufactured in Highland Park, the center of Ford's worldwide empire. The sheer motive power required would not be available without 30 million gallons of water per day being converted into steam inside the Ford Motor Company's powerhouse.

Note 1: These are global production figures, minus Canada (Source). | Note 2: The jog in the graph at 1920 is due to the change from fiscal to calendar year reporting. The "1920" in this graph includes totals from mid-1919 through the end of 1920. If all figures were reported by calendar year, the transition between 1918-1921 would appear smoother.

After ten years in operation, Ford's powerhouse became practically idle when the factory began receiving electricity from the even larger and more efficient powerhouse at Ford's River Rouge complex. The waterworks for which the people of Highland Park indebted themselves was no longer necessary. The following year, on May 26, 1927, Ford Motor abruptly ceased Model T production forever. The company relocated its assembly line and corporate offices the following January, reducing Highland Park's tax base by a whopping 33%. The city's population has been declining ever since.

As the years went by, the Ford Motor Company's connection to Highland Park's waterworks faded from public memory. Like other grand public works projects of the era in Detroit and Highland Park, it came to be regarded as a symbol of the community's past "wealth," rather than a costly public liability built on borrowed money.

The Ford Motor Company in Local Politics

The Ford Motor Company had a dominating influence over the local government of Highland Park. Besides the waterworks, there are other instances when Ford exerting undue political influence over local elections. For example, when Woodward Avenue was in need of repaving in 1910, the village council put a $89,000 paving bond issue on the ballot, which won by a landslide. The Detroit Free Press reported:

The Ford Automobile Co. figured considerably in the large majority. It had addressed circulars to its workmen the day before, calling their attention to the condition of the street and the need of paving. It also loaned the use of a number of automobiles yesterday which carried voters from the middle of the city and as far north as the Six Mile road to the voting booths.

("Highland Park bonds are voted." Detroit Free Press, Apr. 23, 1910.)

When it came time for voters to select which paving material to use on Woodward, the Ford Motor Company had an opinion on that, too:

"The biggest taxpayers in the village do not want either asphalt block or brick," said James Couzens, general manager of the Ford Motor company. "What we want is creosote block [the most expensive option] and although the low bid for that material is $145,000, we are willing to pay for it [through taxes], and this concern alone pays one-half of all the village taxes. If we are willing to pay half it seems as though the villagers out to be willing to pay the other half."

("Village paving row gets warm." Detroit Free Press, May 19, 1910.)

Ford workers voted early, the Free Press reported, and "every one of them wore a streamer in the button-hole of his coat with the legend 'Creosote' upon it." ("Highland Park votes creosote." DFP, May 20, 1910.) Ford's chosen paving material won the most votes at that election, and Woodward was repaved with creosote-treated pine blocks later that year.

Workers outside the Ford Motor Company on Manchester Street in 1914.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

The Ford Motor Company became particularly interested in the local elections of 1918, two years after the vote to expand the waterworks. The company was dissatisfied with the village president and two councilmen who faced criticism from certain quarters for establishing a municipal coal yard, where needy Highland Park residents could purchase coal at-cost during a particularly severe fuel shortage. ("A deficit on the balance sheet." Detroit Free Press, Mar. 15, 1917.) Four days before the election, the Ford Motor Company released a statement which began, "Heretofore, the Ford Motor company has taken no part in the political issues before the village, and is not interested therein so long as its affairs are properly managed, its business conducted along efficient lines, and public funds expended in a judicious manner." After mentioning that the company paid 58% of the village's tax revenue, the statement details several financial irregularities that deemed investigation, including the mounting costs of the new concrete reservoir. ("Ford company warns voters." DFP, Mar. 29, 1918.) All candidates endorsed by Ford won at that election. ("283 votes give Ford victory." DFP, Apr. 3, 1918.) A two-week grand jury investigation ultimately exonerated the candidates whom Ford attacked. ("No indictments in suburb probe." DFP, Apr. 18, 1918.)

To Keep the Government "American and Christian"

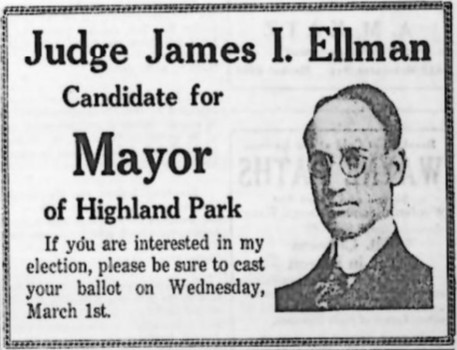

An even more egregious example of Ford Motor Company election interference occurred four years later, during the 1922 mayoral contest. A Highland Park municipal judge named James Isaac Ellmann announced his intention to run for mayor of the city in February of that year. Ellmann, a practicing attorney, served a wide clientele in the immigrant community, himself a Jewish Romanian immigrant and speaker of six languages. In 1916, Ellmann had been involved in a scandal with Highland Park's police chief, whom Ellmann accused of excessive force, unlawful arrests, and "indulging in the use of epithets involving race prejudice." However, a three-member village council committee dismissed the accusations at the time. He was elected as an associate municipal judge two years later. Now running for mayor, Ellmann offered his record of four years of service without any of his rulings being reversed by a higher court as proof that he was "free from prejudice, political, racial or religious." ("Ellmann opens spring campaign." DFP, Feb. 8, 1922) He did not engage in any fundraising activities, but told the media, "I intend to manage my own campaign, prepare my own publicity, and bear my own expenses." ("Judge J.I. Ellmann is candidate for mayoralty of H.P. The Detroit Jewish Chronicle, Feb. 24, 1922.) In the three-way mayoral primary on March 1, Ellmann placed second, behind incumbent Edgar F. Down. The two would advance to the general election on April 3.

Advertisement from The Detroit Jewish Chronicle, Feb. 24, 1922.

(Detroit Jewish News Digital Archives)

In mid-January 1922, less than a month before Ellmann announced his candidacy, The Dearborn Independent—a newspaper published on Ford Motor Company property and owned by the company's founder—included an article on what it called "the Jewish problem," which stated in part:

The Jewish Question will be solved, and its solution will begin in the United States [...] To keep American and Christian, the school, the church, the legislature, the jury room and the Government, is the most potent resistance that can be made to the evil influences which have been upon us and which this series of articles has partly uncovered.

("An address to 'Gentiles' on the Jewish problem." The Dearborn Independent, Jan. 14, 1922.)

The front page of the January 14, 1922 edition of The Dearborn Independent.

(Hathi Trust)

In his book, The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and the Rise of the Third Reich, author Max Wallace observes, "in February 1922 [The Dearborn Independent's anti-Semitic] campaign came to an abrupt halt. Like much in Henry Ford's history, there are conflicting explanations for the sudden retreat." (p. 26) Could Ellmann's candidacy be what initiated this change?

Less than two weeks before the April 3 general election, the Ford Motor Company published a prominent advertisement in The Highland Parker strongly endorsing Ellmann's opponent. Some critics suggested this was motivated by a $24 million reduction in the Ford Motor Company's tax assessment under Mayor Down's administration, while residential property taxes actually increased. ("Ford co. gets into H.P. fight." DFP, Mar. 24, 1922.) The Highland Park League of Women Voters issued a circular in support of the incumbent mayor. "This campaign is not waged against the creed or nationality of either candidate," the League stated, "but on their personal records, which are open to every citizen of Highland Park." Ford's advertisement in The Highland Parker, however, remained "the center of the campaign," according to the Detroit Free Press. ("4 Wayne cities elect Monday." DFP, Apr. 2, 1922.) Unfortunately a copy of the actual advertisement is currently unavailable. However, the event made national news, as seen in the New York Times article below.

The New York Times, March 24, 1922.

(newspapers.com)

Ellmann lost the election, with 3,082 votes to Down's 4,206. An article in the April 14, 1922 edition of The Detroit Jewish Chronicle relates the story:

Judge James I. Ellmann, defeated candidate for mayor of Highland Park, in a post-election statement, says that he was defeated by the Ford Motor Company, and states that if a racial issue had not been made of his candidacy he would have been elected.

Judge Ellmann tells of the methods followed by the Ford people in seeking his defeat. He says that workers at Ford's were threatened with explusion from their jobs if they voted for Ellman [sic]. For days the company distributed cards among the workers telling them to vote for Down, the opponent of the Jewish candidate.

In answering the Ford Motor interests to their paid advertisement against his candidacy, Judge Ellmann said among others:

"How do you reconcile your present course with the American tradition of a free and untrammeled expression of the ballot box from every man and woman, irrespective of the wishes of their employers? Do you question the intelligence, the patriotism and the independence of thought and action of every person other than yourself?

"For several years Senator Newberry has been hounded because of claimed excessive expenditures in gaining public office. What can my fellow citizens do to answer to a corporation that abuses its tremendous prestige and power to injure a candidate fighting alone and unassisted financially by any person or group? I am sure the people of Highland Park will know how to resent in a decisive manner this attempt at domination."

(Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University)

Closing Reflections

When the automobile market was new, the Ford Motor Company had one shot, one opportunity to seize everything it ever wanted. By building the largest factory complex on the planet and flooding the market with as many automotive products as possible, Ford Motor gained a permanent foothold in the industry. Two-thirds of all Model Ts ever built were manufactured between 1921-1927. By the end of that period, half of all vehicles on the road were Fords, and the company's founder had become the first proven dollar billionaire in the world.

The history of the Ford Motor Company would have turned out very differently if its colossal Highland Park complex powerhouse had been forced to rely solely on Detroit municipal water. Fortunately for Ford, the people of Highland Park chose essentially to invest in company by constructing a waterworks system which turned out to be every bit as vital to Ford's operations as any part of the factory proper. In addition to ensuring more reliable water pressure, Highland Park's waterworks also lowered the rate which the company paid for water. When Ford increased its water demands to 30 million gallons per day, the people of Highland Park hardly balked, multiplying the waterworks' output fivefold at great expense to themselves. Ford Motor repaid their good faith by leaving town long before those bonds were paid off, taking one-third of the city's tax base with them.

In conclusion, I offer the following questions for your consideration:

- Would the Ford Motor Company be a top automobile manufacturer today if the people of Highland Park had not supplied the water required by the company's powerhouse?

- Could the waterworks project have been opposed anyway, given the Ford Motor Company's domination of local politics?

- Would the city be experiencing a water affordability crisis had it simply remained a Detroit water customer like other suburbs (e.g. Hamtramck)?

- Do you know of anybody possessing the financial and engineering resources necessary to assist the people of Highland Park in ensuring a safe and affordable supply of drinking water in a manner of their choosing?

Paul, I request the honor of meeting you for a tea, lunch, or bruch 20 minute collaboration. Thank you!

ReplyDeleteHi TriuneCitay: Please email me at my first and last name in all lower case letters without spaces or punctuation, at Gmail dot com. Thanks!

Delete