(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

This is the fourth installment in an ongoing series covering the development history of Highland Park:

- Part I: Before Ford explores the early origins of the Village of Highland Park as an upper-class suburb which had to borrow heavily in order to provide basic services.

- Part II: The Road to Cityhood covers the effects of Henry Ford's arrival on the village and influence afterward. Included is a detailed history of the city's original waterworks.

- Part III: Ford Gave and Ford Hath Taken Away shows how the city engaged in a building program culminating with the McGregor Library, right before Ford abruptly terminated Model T production in 1927, triggering Highland Park's nearly 100-year population decline.

The subject of today's post is the Davison Freeway—the original, which was open from 1942 until 1996, when it was rebuilt completely. This is the history of how a residential street in Highland Park came to be among the first modern urban expressways in the nation, and how planners at the time came to favor freeway construction within densely populated cities.

Davison Avenue

Davison Avenue in Highland Park, July 1941, facing east toward Woodward.

(Virtual Motor City)

Because the Village of Highland Park was originally intended to be a residential suburb, the subdivisions within it were designed so that residents could walk to streetcar lines on the major north-south streets that led to Detroit. Early developers didn't foresee a time when Highland Park would be engulfed by Detroit's street grid, bringing with it traffic which required east-west crosstown routes. Davison Avenue was the only street in Highland Park to cross Woodward without a jog, and one of only three streets that originally crossed the city's eastern border with Detroit (the others being Six Mile Road and Connecticut Street). Being the only usable crosstown thoroughfare between Grand Boulevard and Six Mile Road, as vehicular traffic increased, the narrow residential street became intolerably congested. A 1940 traffic study found that Davison Avenue carried more than 15,000 vehicles in one 14-hour period, 90% of which was non-local traffic, only passing through Highland Park because it was the only option. The entire street would reportedly jam at every rush hour, which would often impede the flow of traffic on the busy north-south avenues.

Davison Avenue at Woodward in 1932.

(Virtual Motor City)

Plans for widening Davison Avenue date back at least to the early 1920s. On Detroit's side of the border, one such project was cancelled in the spring of 1921 because a simple repaving job was more urgently needed. The Detroit Free Press reported that "the street is now in a deplorable condition, and in parts it is practically impossible for automobiles to get through." ("Council drops plan for widening Davison." DFP, Apr. 19, 1921.) As Detroit was planning to widen the part of East Davison Avenue adjacent to Highland Park's waterworks, it was necessary for Highland Park to grant a road easement on this property. ("Suburban." DFP, Dec. 27, 1922) To this day, the sidewalk in front of the Highland Park filtration plant lies partially over the underground filtered water reservoir.

Facing east on Davison, east of Woodward, July 1941.

(Virtual Motor City)

The desire to transform Davison Avenue into a wider traffic artery is reflected in Detroit's 1925 Master Plan of Superhighways and Major Thoroughfares, on which multiple government agencies collaborated, including the Wayne County Road Commission. The plan called for widening Davison's right-of-way to 120 feet, about double what it was at the time.

Detail from Master Plan, Super-Highways and Major Thoroughfares for Detroit and Environs, January 1925. (Highlight added.)

(Hathi Trust)

The prospect of Davison becoming a new major traffic artery attracted the attention of candy maker Fred Sanders, founder of Sanders Confectionery. He purchased land on Woodward Avenue one block south of Davison for his eleventh store, being his first in Highland Park. When announcing the new location, Sanders said, "In addition to the accessibility of this section for all residents of Highland Park, the widening of Davison avenue both east and west of Woodward avenue, makes this location equally as accessible to residents of the northeast and northwest sections of the entire metropolitan area." ("Firm proves faith in city." DFP, Nov. 24, 1929.) The store, which opened to the public in April 1930, was designed by Detroit architects Pollmar and Ropes. ("New chain started in Highland Park." DFP, Jan. 20, 1930.) It would be at least another decade before Davison in this part of Highland Park saw any transformation.

Sanders Confectionary (1930), 13319 Woodward Avenue.

Image from the April 8, 1930 edition of the Detroit Free Press

(freep.newspapers.com)

Widening Davison Avenue in Detroit entailed an extremely lengthy and expensive condemnation process during the 1920s. A lack of funding pushed the project back until the early 1930s. Money was so tight that Detroit had to borrow to cover property condemnation awards and even attempted (unsuccessfully) to persuade the Wayne County Road Commission to reimburse some of the costs. Detroit and Highland Park had both maxed out their debt by the late 1920s, and each struggled to pay for the ever-increasing demands for automotive infrastructure. Hoping that the county might be able to offer some relief, the Highland Park city council in July 1932 granted the county road commission authority to maintain and improve Davison Avenue within its borders. ("Police budget boost delayed." DFP, Jul. 12, 1932.) Highland Park began condemning land along Davison the following month, but only for two blocks at the western end of the city, between Thompson and Lincoln streets. Between July and August of 1933, workers were pouring concrete for this portion of wider Davison. "Welfare labor recruited from Highland Park was used on the grading and construction work," it was reported. ("Around the town." DFP, Jul. 28, 1933.)

This August 1932 photograph shows progress on widening Davison at Highland Park's western border. Building removal had begun, and the new road would be constructed the following summer, but only west of Lincoln.

(Virtual Motor City)

This was how Davison remained for the remainder of the decade: the street had been widened in Detroit and for two blocks at Highland Park's west end, but remained a narrow bottleneck through most of the city. Highland Park took no further steps to widen this 1.3-mile stretch for several years, never having recovered financially from the Ford Motor Company's abrupt departure.

Detail from a 1935 Wayne County road map. Davison was one of just a few crosstown routes in the vicinity of Highland Park.

(Dearborn Historical Museum)

Promoting the Urban Expressway

Highland Park happened to be seeking a solution to its Davison Avenue congestion problem at a unique moment in American history: the automobile industry was about to convince urban planners that the solution to automobiles crowding city streets was not to divert passenger vehicles away from densely populated urban areas, but rather to construct new expressways carrying as many vehicles as possible directly through them.

Image of the "City of Progress" with an urban expressway, from GM's Parade of Progress, launched in 1936.

(Semantic Scholar)

At the close of the 1933-1934 "Century of Progress" World's Fair at Chicago, General Motors Vice President Charles F. Kettering had an idea to create a touring roadshow version of his company's exhibits, along with whole new displays. The result was GM's "Parade of Progress," a quasi-educational traveling carnival intended to show Depression-weary Americans the fantastic wonders which the corporation was making a reality through the power of science. The show was transported by a motor caravan, originally headed by a line of eight streamlined vans (later replaced by a fleet of twelve gleaming "Futurliners)." This "circus of science" left Detroit for its first tour of towns across North America in January 1936. ("G.M. caravan off for Florida." DFP, Jan. 30, 1936.)

(carzhunt.blogspot.com)

The Parade of Progress dazzled audiences with examples of technological progress, ranging from induction cooktops to the miracle of leaded gasoline, one of Kettering's own patented inventions. There was also an exhibit on urban planning, which one local newspaper described when the caravan stopped in York, Pennsylvania: "Transportation is represented by what is said to be the largest moving diorama ever built, the 'City of Progress' showing elevated highways upon which 200 hand-carved automobiles and trucks are in constant motion. Below the highway, are depressed tracks for Diesel streamlined trains. Opposite the modern scene is a diorama of 'Main Street in the '90's' with delapidated [sic] trolley and 'horseless carriage', both in motion." ("Prepare for exposition opening here." The Gazette and Daily (York, Pa.), Jul. 14, 1936.) Another paper noted the "elevated highway without intersections, designed for maximum safety in the movement of cars, trucks and buses" in the "City of Progress." ("Progress Parade coming to Biloxi." Sun Herald (Gulfport, Miss.), Dec. 15, 1936.) Within four years, the Parade of Progress had educated and entertained eight million Americans in more than 200 towns and cities.

The "City of Progress" model from General Motors' Parade of Progress.

From the Oct. 4, 1939 edition of the Akron Beacon Journal.

(newspapers.com)

Writing about GM's Parade of Progress in 2016, architectural historian Nathaniel Walker observed, "At the heart of this campaign was a desire—publicly articulated by [Kettering]—to remake the North American landscape so that the automobile was elevated to a required necessity of daily life, alongside housing, clothing, and food." ("American crossroads." Buildings & Landscapes, Fall 2016.) This is no exaggeration—click here to read Kettering's own writing on "the new necessity."

Charles F. Kettering, August 1936.

(Scharchburg Archives, Kettering University)

General Motors would not be alone in the futuristic miniature model making business for long. While the Parade of Progress was still in its first year, Shell Oil had contracted with industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes to collaborate on an advertising campaign with a futuristic theme. Geddes, a former theatrical set designer, convinced Shell to finance the construction of a model city and countryside displaying traffic solutions twenty years in the future. To give the project scientific credibility, Shell Oil hired the best consultant on the future of road design they could find, an individual once referred to as "the first man ever awarded a doctorate in traffic." ("Highways cannot do job now." The Windsor Star, Aug. 8, 1936.)

Miller McClintock gained credibility as a traffic expert for a 1923 Los Angeles traffic study, which became the basis of his doctoral thesis. After Harvard University granted him a PhD in 1924, the Los Angeles Traffic Commission hired him as an advisor on the revision the city's traffic code and road design. "McClintock's job was to work out efficient traffic flow downtown by regulatory means," writes historian Peter D. Norton, in Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. "His ordinance included strict pedestrian control measures, with fines for jaywalkers," (p. 164) methods justified by a reduction in fatalities and increase in traffic flow. The president of the traffic commission happened to be Paul G. Hoffman, a Studebaker employee since 1911. After Hoffman's 1925 promotion to vice president of sales at the company, he convinced president Albert Russel Erskine to financially support McClintock's work, creating the Albert Russel Erskine Bureau for Street Traffic Research. "In 1926, however, Studebaker moved the Bureau and its director to Harvard University. There it presented itself as a Harvard University research institute...." (Norton, p. 165) And that is how the Studebaker Corporation helped remake a former reporter and college professor, whose master's degree was in English literature, into Dr. Miller McClintock, Director of the Harvard University Traffic Research Bureau.

Dr. Miller McClintock

(Stanford Historical Photograph Collection)

As the public became increasingly alarmed at the growing number of deaths resulting from motor-vehicle crashes, the automotive industry desired a "scientific approach to a solution of the traffic problem, believing that the same methods which have given America safe cars will protect their safe use," as stated in the Automobile Manufacturers' Association's Highway Safety Policies. In rural areas, where cars were increasing mobility, this included common-sense reforms such as separating opposing lanes of traffic and illuminating highways at night. But in cities, where automobiles jammed streets and killed pedestrians, finding a "solution to the traffic problem" which shifted all culpability away from automobiles and their operators—not to mention their manufacturers—would require the unquestioned authority of a scientific expert.

From the 1936 edition of Automobile Facts and Figures.

(Hathi Trust)

Automakers increased their financial support for Dr. McClintock in December 1935, when the Automobile Manufacturers' Association donated $54,250 to the Harvard University Bureau for Street Traffic Research. This allowed Dr. McClintock to continue his traffic studies while expanding the department, creating and graduating additional traffic experts like himself. The donation was just the beginning of "a long range program to reduce traffic's toll in death and injury, yet facilitate its movement on the streets of American cities." ("Add to traffic study." The Kansas City Star, Dec. 18, 1935.) With the goal of moving as many motorized vehicles through a city as possible, it is perhaps no surprise that Dr. McClintocks' research invariably blamed congestion and fatal collisions on outdated street design and poor pedestrian behavior. Automakers presented themselves as beacons of scientific progress, while cities and their primitive streets were dangerously outdated and required immediate modernization. According to the Harvard University Bureau for Street Traffic Research, cities needed to catch up to the auto industry's level of progress by building what Dr. McClintock called "limited ways"—limited-access freeways built above or below street level designed to eliminate intersections.

Examples of "limited ways" in New York, both "depressed" and "elevated," from Dr. McClintock's 1933 report for the City of Chicago.

(Hathi Trust)

In January 1936, the month following the Automobile Manufacturers' Association's donation to Dr. McClintock, the organization launched a major nationwide safety campaign just before GM's inaugural Parade of Progress tour. Claiming that they had already done all they could to improve car safety (more than a decade before seatbelts were offered as a factory option), automakers blamed the government for traffic fatalities, claiming that what was needed was investments in new infrastructure, including the construction of "limited ways" through densely populated areas. "The primary responsibility for highway safety belongs with the public officials, who are charged with the duty of building and maintaining the facilities and controlling their use," said the AMA's chairman and Studebaker Vice President Paul G. Hoffman, when announcing the campaign. ("Industry plans a safety drive." DFP, Jan. 22, 1936.)

The Beaver Crossing Times, Mar. 3, 1938.

(newspapers.com)

The year after the AMA launched its safety drive, Detroit hosted the 1937 National Planning Conference, held between May 31 and June 3 at the Statler Hotel, attracting more than 200 city planning professionals from across the country. The closing presentation of the morning session the first day was delivered by Dr. McClintock. His speech, "Of Things to Come," opened by addressing problems associated with the "automotive revolution," wondering whether the automobile "will develop into a partially malignant growth or a pearl of great price." Acknowledging that the nation's annual automobile fatalities had surpassed 36,000, he cautioned "nor can we, in this mechanized age, look with tolerance upon the shackles which fetter this newest servant of mankind."

(National Safety Council)

Dr. McClintock's speech dismissed measures such as installing speed limiters on cars, or addressing antisocial driver behavior. Instead, "the street and highway systems of the nation must be rebuilt ... [O]ur urban areas must be provided with rapid transit facilities for automotive traffic just as, in the past, the major cities have been provided with rapid transit for mass carriers." "The city of tomorrow," he said, "will be an automotive city." After touching upon some of the types of traffic remedies he had in mind, Dr. McClintock revealed, through projected photographic slides, Geddes' Metropolis City of 1960 to the public for the very first time, dramatically illustrating the industry's solution to the problem of urban traffic.

Detail from Metropolis of 1960.

(Wikipedia)

The Detroit Free Press reproduced one of the model city photos on display at the Statler, noting the "high speed express highways that eliminate intersections and make all parts of the City accessible." Later that year, Geddes' model appeared in Shell Oil advertisements printed in Saturday Evening Post, Life, and Collier's magazines. The physical model itself was transported to Milwaukee for the auto show there that autumn, where it was "one of the most popular features," according to one paper, remarking that Geddes "has portrayed his idea of the Milwaukee of 1960, when traffic problems will be a thing of the past." ("Auto show draws capacity crowds; features 'city of tomorrow' display." The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, Nov. 19, 1937.)

(Wikipedia)

Later that summer, Detroit hosted another major national conference: the 67th annual convention of the American Society of Civil Engineers, held July 21-24, 1937, also at the Statler. Kettering of General Motors addressed the roughly 1,000 delegates on the opening day, briefly covering the subject of urban expressways in his speech on future trends in civil engineering:

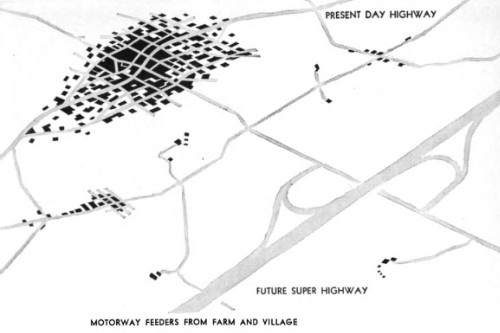

[Some] believe that faster means of transportation from outside into the center of large cities is coming. Workmen could live as much as 50 miles from their work. Homes would be located on large plots in the open country. The city would be for work, business, and commerce. To accomplish this would require high speed, limited access trunk highways to the city limits. The city would have many elevated or depressed highways crossing it in every direction. Present level streets would be used for local travel. Local conditions will govern whether we built underground or overhead. [...] The best road for the automobile will have the least obstructions to the steady flow of traffic. Whether this means limited access "freeways" such as Germany is building in their Reichsautobahn, I don't know.

("Motor Vehicles and Highways of the Future," National Petroleum News, Aug. 4, 1937.)

Norman Bel Geddes and Charles F. Kettering, circa 1940.

(New York Public Library Digital Collections)

That summer, the Michigan State Highway Department and the Detroit Police collaborated on a thorough study of Detroit street traffic. Their report recommended widening Vernor Highway and creating two new crosstown routes by enlarging and connecting preexisting streets, highlighted in the image below. But these were just wider, ordinary roads, not the "limited ways" described by Dr. McClintock, who did not consult on this report.

Michigan State Highway Department, "Major Street Improvements Recommended for Immediate Construction," Street Traffic, City of Detroit, 1936-1937. (Highlights added.)

(Hathi Trust)

Had McClintock participated in Detroit's traffic study, he might have proposed something like the $100 million, 160-mile network of elevated expressways which he unsuccessfully recommended for Chicago in 1933. San Francisco likewise received similar advice from Dr. McClintock, who "recommended the city spend $26,120,000 in girdling and piercing itself with a system of elevated and depressed high-speed roadways to ease its aching traffic pains," a plan which was also rejected. ("Report on S.F. traffic 'cure' stirs dispute." San Francisco Examiner, Aug. 4, 1937.) Although there were some limited-access roads seen in a few US cities, the public by and large hadn't quite warmed up to auto manufacturers' vision of the future. At least not yet.

In anticipation of the 1939 New York's World Fair, Norman Bel Geddes planned an even larger model city with urban highways as part of an exhibit for Goodyear Rubber, who abruptly pulled out of the fair in February 1938. Undeterred, Geddes approached General Motors and talked them into building what would become one of the most ambitious world's fair attractions of all time. (Marchland, Roland. "The Designers Go the Fair II," Design Issues, Spring 1992.) This new, multi-million dollar, fully-immersive city of tomorrow covered nearly an acre, containing 50,000 tiny cars, 500,000 model buildings, and one million miniature trees. Although GM executives were initially reluctant to fund the exhibit, Futurama turned out to be one of the most popular attractions in the history of world fairs. By the closing of the event in October 1940, approximately five million visitors witnessed how wonderful their future might be if only their rebuilt their cities around the automobile.

(Source)

"Every effort should be made to push Detroit to the front in modernizing its traffic facilities, because of its position in the automotive industry. ... The automobile manufacturing industry is convinced that the sale of more cars depends in part on having good roads and streets. The General Motors exhibit of the city of the future at the New York World's Fair is an indication that they are traffic conscious."

—Murray D. Van Wagoner, Michigan State Highway Commissioner

("Progress cited in state roads." DFP, Jun. 3, 1939.)

In the same year that the fair opened, the US Bureau of Public Roads released a report which would be influential in the establishment of the Interstate Highway System. Written by highway engineer Herbert S. Fairbank, Toll Roads and Free Roads states that remedies such as road widenings are insufficient to address city congestion. "In larger cities generally only a major operation will suffice—nothing less than the creation of a depressed or an elevated artery (the former usually to be preferred) that will convey the massed movement pressing into, and through, the heart of the city, under or over the local cross streets without interruption by their conflicting traffic." (p. 93)

Below-grade urban expressway illustration from Toll Roads and Free Roads (1939).

(Hathi Trust)

The Creation of the Davison Freeway

(archive.org)

After taking no action on Davison Avenue for several years, the Highland Park City Council appointed a 14-member committee in November 1938 to investigate several proposed city street widening projects, including Davison. In January 1939 the committee reported back with the following plan for Davison: that the city ask the Wayne County Road Commission to pay all construction costs, pay all condemnation awards, build the road, and then pay the city $20,000 each year for ten years "to offset the lower assessed value of the property." Highland Park approached the county with this offer, but it was ultimately declined. ("Highland Park's proposal for widening is rejected." DFP, May 2, 1939.)

Facing east from the northwest corner of Davison and Woodward, July 1941.

(Virtual Motor City)

Highland Park had to resort to such bold moves because the city simply didn't have the money that it used to. Wayne County, however, was about to receive an $8 million chunk of state highway construction funds. Michigan collected $48 million in gasoline and vehicle weight taxes in the fiscal year 1938-1939, which funded the State Highway Department, which dispersed the money to the various county road commissions across the state. ("Are you aware?" DFP, Mar. 16, 1940.)

A political controversy unfolded over how to spend Wayne County's $8 million, which centered around an upcoming vacancy on the Wayne County Road Commission, whose job it was to spend that money. Detroit officials complained that the commission was spending more on suburban projects, even though most of the tax revenue was coming from Detroit, so they supported challenger Philip Neudeck. The suburbs, of course, wanted to keep incumbent John F. Breining. The choice was up to the Wayne County Board of Supervisors, then composed of 152 members from every municipality in the county, including both Detroit and Highland Park. The board deadlocked on the issue in April 1940, but planned to reconvene for another vote the following June.

Facing west down Davison from east of Woodward, July 1941.

(Virtual Motor City)

That May, Highland Park City Engineer Lawrence C. Whitsit announced that the city had reached a tentative agreement with the Road Commission, wherein Highland Park would contribute just $100,000 to widen Davison Avenue, and the county would cover all the remaining costs, then estimated at $1.5 million. ("County board reopens issue." DFP, May 15, 1940.) Some were suspicious of political dealings. Hamtramck delegates on the Board of Supervisors were accused of favoring Breining in exchange for a new city park, according to one news report at the time. "Highland Park, too, will swing for Breining if rumors are true," the article stated. ("County board to vote again." DFP, Jun. 24, 1940.) That is at least what one anonymous source told Detroit Free Press reporter Leo Donovan: "The City of Highland Park will have Davison widened through the County Road Commission's good graces at a cost of only $100,000 payable in five years without interest, according to the informer," Donovan wrote. "Yet the widening of Davison in Detroit was not accomplished with County Road Commission funds, he pointed out." (Donovan, Leo. "Will Neudeck unseat Breining?" DFP, Jun. 23, 1940.) The suburban faction ultimately prevailed, reelecting Breining to the road commission that June.

Members of the Board of Wayne County Road Commissioners at the future site of the Davison Freeway. From left to right, commissioners John F. Breining, Charles L. Wilson, and (possibly) Michael J. O'Brien; far right: Leroy C. Smith, director and engineer.

(Virtual Motor City)

The timing was perfect for government officials to favor converting Davison Avenue into a limited-access highway rather than just a wider surface street. Urban expressways had by now gained legitimacy among highway engineers, not that the idea needed the hard sell in Michigan. State Highway Department Commissioner Murray D. Van Wagoner announced in 1939 that the new crosstown route along McGraw and Harper avenues—today's I-94—would not be just another arterial road, but a modern limited-access highway. The Detroit Free Press reported that the highway "might be an elevated structure." ("Federal funds sought for city superhighway." DFP, Jul. 28, 1939.)

Professionals were recommending limited-access highways for the Detroit area by 1941, when the Michigan State Highway Department published A Comprehensive Plan of Motorways for Detroit.

Professionals were recommending limited-access highways for the Detroit area by 1941, when the Michigan State Highway Department published A Comprehensive Plan of Motorways for Detroit.(Hathi Trust)

Although construction on the McGraw-Harper highway would be delayed until after World War II, the Davison project progressed rapidly from this point. Several months after Breining's reelection, the Wayne County Road Commission included the Davison project in its 1941 construction budget. ("County road budget for '41 is estimated at $8,505,224." DFP, Sep. 22, 1940.) The Highland Park City Council officially consented to the Wayne County Road Commission beginning the project on March 17, 1941, and work began immediately. ("Sunken highway begun at Davison bottleneck." DFP, Mar. 18, 1941.) The Road Commission's annual report, released in April 1941, explained that the Davison Limited Highway was necessary in order to remedy traffic congestion, which in part was affecting Detroit's ability to manufacture munitions for the war effort. The report urged the construction of additional limited access highways like the Davison in and around Detroit. ("Auto, gas taxes add 5 millions to city income." Detroit Evening Times, Apr. 16, 1941.)

Facing east down Davison from Hamilton with ruined house foundations in the foreground. The water tower on the horizon is part of the Highland Park waterworks, at Davison and Dequindre in Detroit.

(Virtual Motor City)

Advertisement from the April 25, 1941 edition of the Detroit Free Press.

(freep.newspapers.com)

The first work to be done upon groundbreaking on March 17, 1941 was initial removal of the 132 structures which stood in the freeway's path, although not all properties had been obtained by that date. In order to acquire the 204-foot-wide swath of land necessary, planners condemned all properties on the south side of Davison up to the back alley. Workers demolished 69 homes and businesses structures, in addition to moving 63 residences intact to other sites. The County Road Commission used one particular house—65 West Davison, seen in the photo below—as a field office temporarily.

Looking west down Davison from the southeast corner of Woodward, July 17, 1942. The building in the foreground was built by Fred Sanders in 1930.

(Detroit Historical Society)

Engineers Harry A. Shuptrine and Julian C. Mead of the Wayne County Road Commission wrote an informative two-part article about the "Davison Limited Highway" in the December 1942 and January 1943 editions of Civil Engineering. They explained that a costly overhead viaduct was considered for Davison but rejected, and making the road wider simply would not have been sufficient:

[I]t was quite clear that under the existing conditions no advantage could accrue to traffic, commensurate with the cost involved, through a purely surface development of wider right of way and pavement for Davison Avenue from Hamilton to Oakland. To reap any material advantage, it was necessary that the grades be separated at each of the seven crossings and that local traffic on Davison be segregated from through traffic. Since these crossings are from 700 to 900 ft apart, a continuous limited highway was obviously indicated.

(archive.org)

According to the project's design, the old Davison Avenue would more or less became the north service drive for the new freeway. The first concrete poured on the project was on the south service drive, starting September 1941, by the Weird Construction Company. Excavation for four of the freeway's seven overpasses began in November, after the William J. Storen Company's successful bid for the job. Completed in July 1942, these four identical, single-span, reinforced-concrete bridges carried traffic for Third, Second, John R, and Brush streets.

Facing south down Third Avenue from the north side of Davison, November 21, 1941.

(Virtual Motor City)

Had engineers attempted to build a raised viaduct over Davison Avenue, the job would have been delayed until after World War II, if not cancelled, due to the demands for steel at the time. Years before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the US had been ramping up munitions production, both for domestic rearmament and to supply arms to Great Britain. War production was lifting Detroit's economy to highs not seen since 1929. With US steel mills running at capacity, the government imposed limitations on the use of steel in construction. But because Detroit was heavily involved in arms production, and traffic congestion slowed down the movement of workers and materials, the federal government concluded that the Davison Freeway was beneficial to the war effort and was a worthy use of resources. According to an article by historian Charles K. Hyde in the Michigan Historical Review:

In August 1941, at the start of construction, the federal Office of Production Management (OPM) recognized the Davison Limited Highway's importance to defense production by granting the project a favorable priority preference rating of A-10, which allowed scarce materials, particularly steel, to be used in construction. The OPM upgraded the rating in November 1941. The Davison design, featuring reinforced concrete pavements ten inches thick and rigid-framed reinforced-concrete bridges (versus steel-girder design), kept steel requirements to a minimum.

Here, 29-foot steel rebar is being bent into the required shape using a template, due to the problems involved in shipping pre-bent bars through city streets.

(Detroit Historical Society)

The three remaining bridges—Woodward, Hamilton, and Oakland avenues—required greater capacity due to the heavy streetcars which they would carry, and were therefore designed as double-spans. The William J. Storen Company constructed these bridges as well, beginning in March 1942. One-half of each bridge was built at a time in order not to disrupt streetcar service.

The Woodward Avenue overpass, from the September 13, 1942 edition of the Detroit Free Press.

(freep.newspapers.com)

The original intention of the highway was to separate local from express traffic. Earlier studies had shown that 90% of the vehicles jamming Davison were not local traffic, but only passing through Highland Park because few other routes were available. Therefore, the below-grade express lanes were only accessible at either end of the project. Local traffic within Highland Park would primarily use the service drives, while "through" traffic from Detroit moved unimpeded along the express lanes below. This separation was so distinct in its original design that it didn't even contain entrance or exit ramps at Woodward Avenue. There were, however, accommodations for bus passengers at Woodward and Davison, consisting of a bus stop in the freeway (seen in the photo below) and stairs for the passengers.

A group of bus passengers appear to have disembarked from a Davison bus and are approaching the stairs leading up to Woodward, circa 1949.

(Hathi Trust)

The general excavation contract for the project was awarded to Charles J. Rogers Inc., who bid $327,374.50 for the job. The company's removal of 320,000 cubic yards of earth began in April 1942.

Excavation east of Hamilton, early 1942.

(Virtual Motor City)

The Woodward Avenue overpass as the expressway nears completion in late 1942.

(Virtual Motor City)

The "Davison Limited Highway" opened to traffic without fanfare at 5:00 P.M. on Wednesday, November 25, 1942, reportedly ahead of schedule. "The highway is needed so badly that we want to open it as soon as the workmen can complete their job and get out of the way," Leroy C. Smith explained. "Landscaping and other finishing touches will continue for some weeks." ("New Davison road to be open today." DFP, Nov. 25, 1942.). The finished highway measured 1.3 miles long, containing three, 11-foot wide concrete travel lanes running in each direction, between 12 to 17 feet below ground level, conveying traffic below seven reinforced-concrete bridges. Project costs totaled approximately $3.2 million, of which $1 million was for obtaining the right-of-way. A drive across Highland Park, which used to take up to 30 minutes at peak congestion times, was reduced to just three.

Overlooking the barely-finished highway from Hamilton, upon opening in November 1942.

Overlooking the barely-finished highway from Hamilton, upon opening in November 1942.(Virtual Motor City)

Although innovative at the time, the original freeway would feel cramped to drivers today. The 204-foot right-of-way did not allow room for a shoulder at the side of the road. One of the project's engineers, Harry Shuptrine, even admitted that the sodded embankments were too steep. (Haswell, James M. "Auto capital displays roads of future." DFP, Jul. 30, 1944.) Initial plans called for the six-foot-wide curbed dividing strip to be simply landscaped with barberry hedges, but some wise engineers decided to erect a more substantial barrier later on.

(Virtual Motor City)

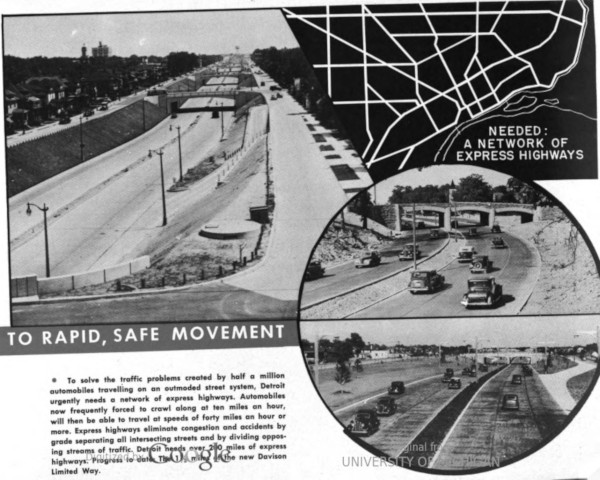

The Detroit Free Press hailed the new Davison Freeway as a "creditable engineering feat ... that is only a beginning of cracking serious bottlenecks in our street system. Others must be remedied as soon as possible." ("A good start." DFP, Nov. 27, 1942.) One trade publication declared that the Davison "takes its place among the pioneer roads of the world and points prophetically to the highways of the post-war period." ("New Urban Highway A Symbol of Future," Contractors and Engineers Monthly, Mar. 1943.) In a mid-1940s informational brochure about an anticipated capital improvement program in Detroit, the City Plan Commission claimed, "Detroit urgently needs a network of express highways" similar to the Davison. With such a system, "automobiles now frequently forced to crawl along at ten miles an hour, will then be able to travel at speeds of forty miles an hour or more. Express highways eliminate congestion and accidents by grade separating all intersecting streets and by dividing opposing streams of traffic. Detroit needs over 200 miles of express highways." Four pages earlier, this booklet had included photographs of Norman Bel Geddes' Futurama exhibit, apparently suggesting it as a model for "the rebuilding of Detroit."

Detroit City Plan Commission, Toward a Greater Detroit (c. 1944)

The images on the lower right show the Willow Run Expressway, west of the city.

(Hathi Trust)

Not everybody was enamored with America's most modern expressway. After the Wayne County Road Commission released a tentative plan of similar sunken freeways crisscrossing Detroit in 1944, real estate analyst Herman J. Brachman waged an unsuccessful fight against building additional city expressways. Brachman suggested limited-access parkways as a more attractive solution, claiming that expressways like the Davison were prohibitively expensive and depressed property values. ("City asked to abandon depressed highway idea." DFP, Jul. 29, 1947.) Writing about Brachman's campaign, Free Press columnist Mark Beltaire remarked, "Judging from the Davison blight, he has something." ("Town crier." DFP, Sep. 8, 1945.)

Facing east down Davison from Hamilton, during and after freeway construction.

(Virtual Motor City, Burton Historical Collection)

The Age of Speed

The Davison was not the first urban expressway in the US, although it was the oldest surviving one by the time it was rebuilt in 1996. There had been limited-access highways in urban locations in the form of parkways and viaducts before, such as Los Angeles' Pasadena Freeway and New York's West Side Elevated Highway. The first depressed or below-grade urban expressway actually opened in Saint Louis on July 19, 1937. But unlike the Davison, the Saint Louis Express Highway was curved, narrowly encased between concrete walls, and lacked sodded embankments and even a center divider. The Davison Freeway was considered to be a far superior design, and a model for future urban expressways.

Pages from a promotional brochure printed by the Portland Cement Association circa 1953.

(Hathi Trust)

Despite the way the Futurama exhibit showcased urban expressways, Norman Bel Geddes later revised some aspects of his vision. "The express motorway of the future will not enter towns or even go from town to town," he wrote in Magic Motorways (1940). "It will pass near to and serve the town." (p. 199) Geddes, himself a resident of Manhattan, added later, "A great motorway has no business cutting a wide swath right through a town or city and destroying the values there; its place is in the country, where there is ample room for it and where its landscaping is designed to harmonize with the land around it." (p. 211)

Illustration from Magic Motorways (1940) by Norman Bel Geddes.

(Hathi Trust)

Herbert S. Fairbank, however, dismissed reasoning like Geddes' in Interregional Highways, Fairbank's 1943 follow-up to Toll Roads and Free Roads which was more or less a blueprint for todays' Interstate Highway System. "On main highways at the approaches to any city," Fairbank wrote, "a very large part of the traffic originates in or is destined to the city itself." (p. 58) Additionally, because city centers often contain the most important government and cultural institutions in the area, "the interregional routes, carrying a substantial part of this traffic, should penetrate within close proximity to the central business area." (p. 61) Incidentally, Fairbank himself daily commuted by automobile 40 miles each way between Baltimore and Washington, DC for most of his career.

Illustration from Interregional Highways (1944) by Herbert S. Fairbank.

(Hathi Trust)

Fairbank's report was influential in the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944, which enabled the federal government to fund the construction of the Interstate Highway System. This was the first time that federal funds were reserved for the construction of highways within cities. The urban expressway had arrived as the legitimate, safe and scientific solution to the problem of city traffic.

To be continued...

Coming soon: Highland Park Part 5: Urban Renewal

So Highland Park was essential the guinea pig for expressways and suburban sprawl. IT hasn't recovered since

ReplyDeleteI agree. HP and Detroit were designed to be serviced by street cars, and both were very much experimented on and disrupted to force them to accommodate excessive automobile traffic. And then the class of people who made those decisions left anyway.

DeleteExcellent article, excellent research. Really enjoyed how the whole process was brought to life.

ReplyDelete