The last of Detroit's radial avenues to be established was Fort Street. In addition to being the youngest and shortest of the radials, it is also the only one never to have served as a US military highway.

The Military Reserve

As its name implies, Fort Street has a connection to Fort Shelby, built by the British as Fort Lernoult in 1779, just north of the original French settlement. When the United States took command of Detroit in 1796, the federal government became the owner of this fortress and all other public land. When the original town of Detroit burned in 1805, the new city was laid out on the public grounds according to Augustus Woodward's plan, and the US government distributed town lots to Detroit's citizens. However, the federal government retained ownership of the fort and the adjacent grounds. This "Military Reserve," as it was called, was exempt from the Woodward Plan.

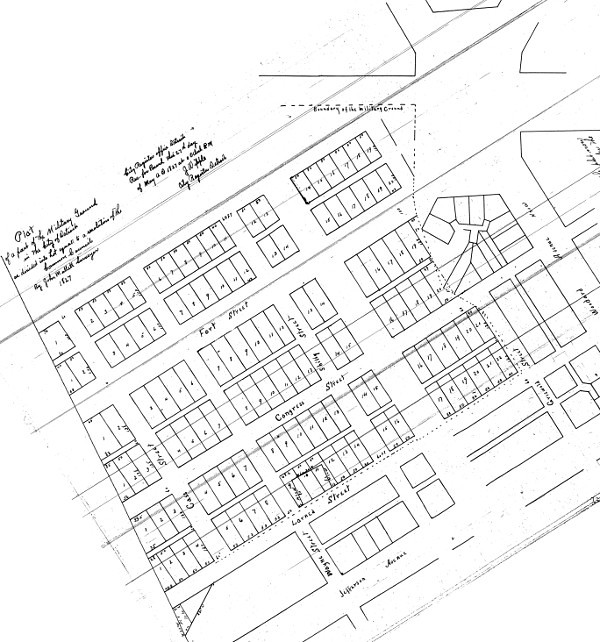

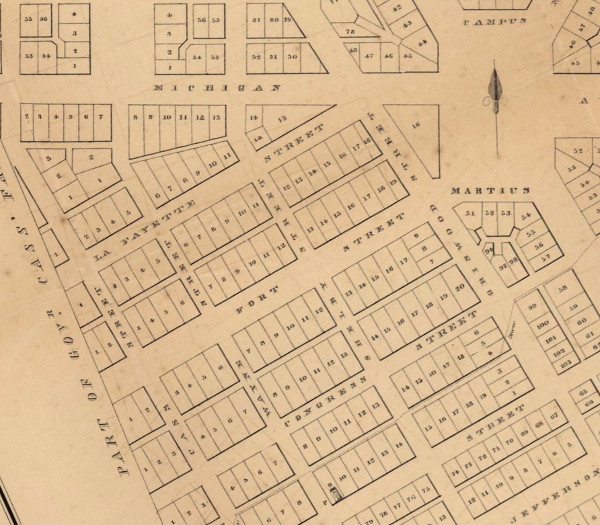

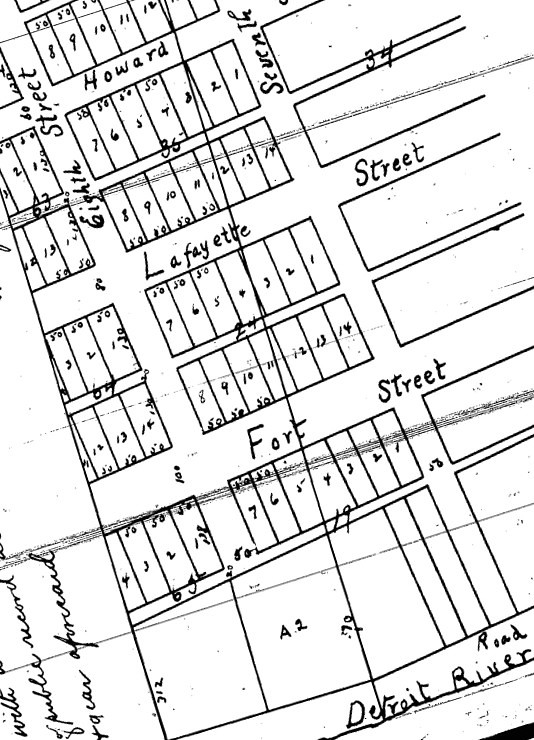

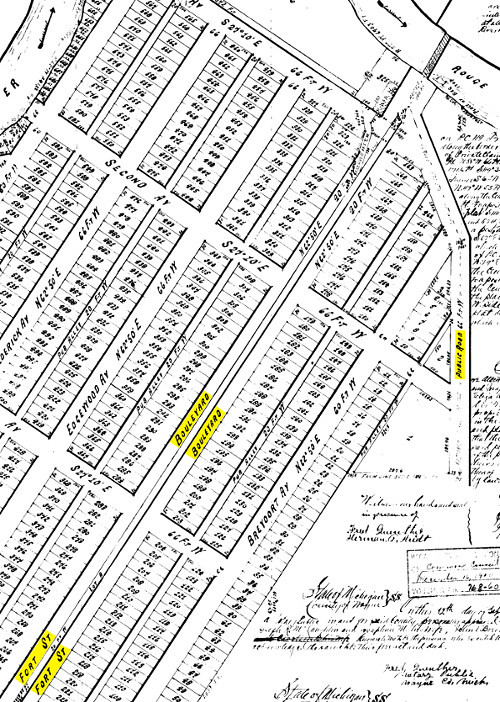

In January 1826, the City of Detroit petitioned Congress to move military operations farther away from the populace, and to inquire how ownership of the military grounds might be obtained by the city. On May 20, 1826, President John Quincy Adams signed "An Act granting certain grounds in the city of Detroit to the Mayor, Recorder, Altermen, and freemen of that city," which gave essentially all of the Military Reserve to the local government on the condition that it fund the construction of a new powder magazine. The transfer was completed on September 11, 1826. Not wanting to subdivide this land according to the Woodward Plan, the Detroit City Council petitioned the Michigan Territorial Legislature for permission to alter the Plan of Detroit. This authority was granted in section 13 of "An act relative to the City of Detroit," passed April 4, 1827. The City Surveyor, John Mullett, immediately drew up the following plat, which was received by the City Register on May 27, 1827. It was here that Fort Street was born.

Although Mullett's plan of conventional rectangular blocks was a rejection of Augustus Woodward's system of interlocking triangles, it was designed to be aligned with Woodward Avenue. Mullett cleverly marked the location of Fort Shelby, dismantled between 1826-1827, by the intersection of Fort and Shelby Streets.

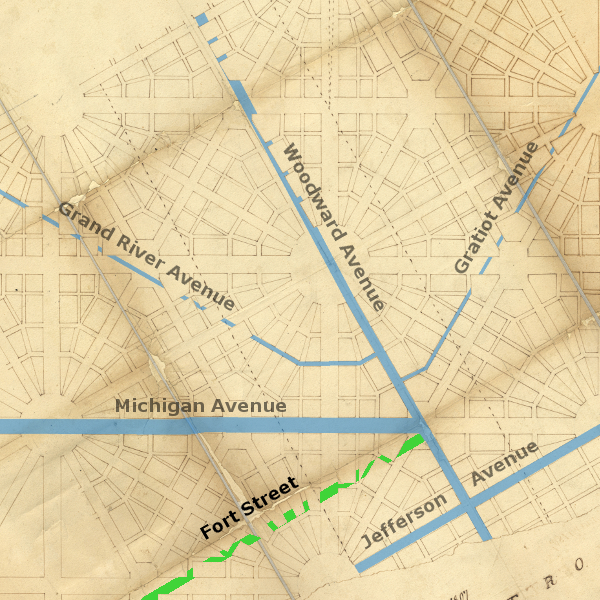

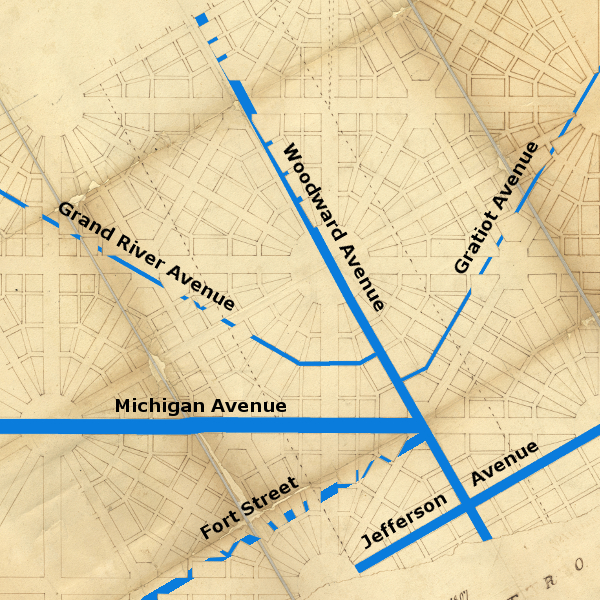

As illustrated in the image at the top of this article, Fort Street was not part of the Woodward Plan. The closest "true" radial avenues that head in the same direction as Fort Street (S 60° W) are Jefferson and Adams Avenues. There should have been a radial avenue beginning at the same point where Fort Street begins (the southwest corner of Campus Martius), but it would have been a continuation of Monroe Avenue, which is built at an entirely different angle. Fort Street is only 100 feet wide, whereas avenues and grand avenues on the Woodward Plan are supposed to be 120 feet and 200 feet wide, respectively. This road was not Augustus Woodward's handiwork.

In September 1827, the Detroit City Council officially opened Fort Street from Campus Martius to the eastern border of the Cass Farm, which is now Cass Avenue.

A Road through Springwells

Extending Fort Street beyond the former Military Reserve became a contentious issue for decades. Citizens of Detroit and Springwells (the township that ran from about Fifth Street to the Rouge River) petitioned the Legislative Council of the Michigan Territory both for and against continuing the street westward. In January 1833, Representative Moran delivered a remonstrance against the road from farmers who lived along the river west of Detroit, claiming that extending Fort Street "will injure many orchards, barns, fences, &c.—besides, they contend that the road along the river is good enough, and better than can be made on the new route."

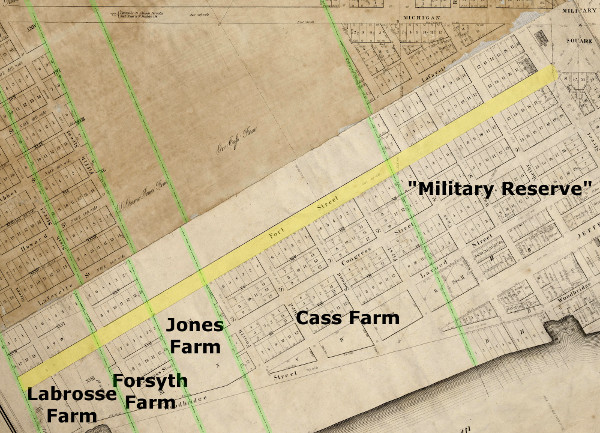

Attempts to continue the road by an act of the legislature in 1833, 1834, and 1835 were unsuccessful. However, the landowners closest to the city were eager to subdivide their farms into building lots, which were in high demand, and the county government had the final say regarding how the land could be platted. In 1835, District Surveyor John Farmer drew up a subdivision plan for the Cass and Jones farms, which were in the City of Detroit; as well as the Forsyth and Labrosse farms, located in Springwells Township. The plat, which was officially recorded by Wayne County in December 1835 with the consent of the landowners, included a continuation of Fort Street through all four farms. This brought the road just past Seventh Street (now called Brooklyn Street).

Fort Street extended about another block when Daniel Baker, owner of the next Springwells property west of the Labrosse Farm, submitted a subdivision plat of his land on October 19, 1836.

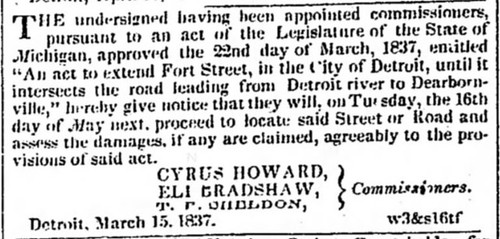

Just after Michigan achieved statehood in January 1837, the nascent legislature passed a law extending Fort Street--at least on paper. On March 22, 1837 Governor Stevens T. Mason signed "An Act to extend Fort Street, in the City of Detroit, until it intersects the road leading from the Detroit river to Dearbornville." The road to "Dearbornville" is today's Dearborn Street in Detroit's Delray neighborhood.

This law empowered the governor to appoint three commissioners to survey the continuation of the road. The commissioners were also to assess damages to property caused by the road's construction. Damages were to be paid for by Wayne County. The men selected for the job were Cyrus Howard, a Wayne County circuit judge from Dearborn; Timothy F. Sheldon, Canton Township Supervisor; and Eli Bradshaw, Surveyor of Wayne County.

For reasons that are unclear, Fort Street was not extended beyond the Baker farm at this time. The survey appears to have been done, but perhaps the legislature withheld funding of the road due to protests from Springwells residents.

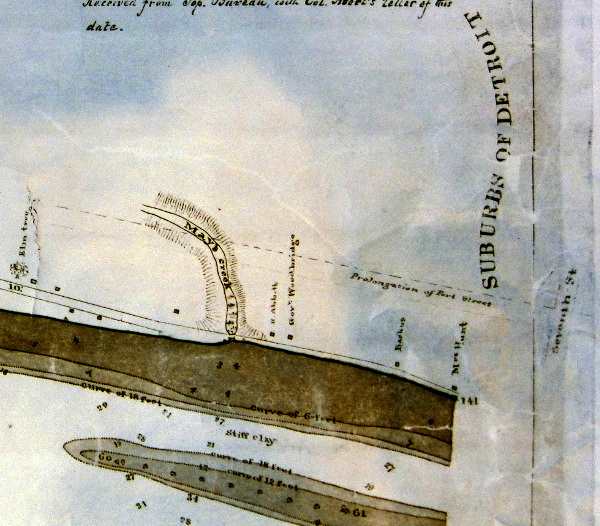

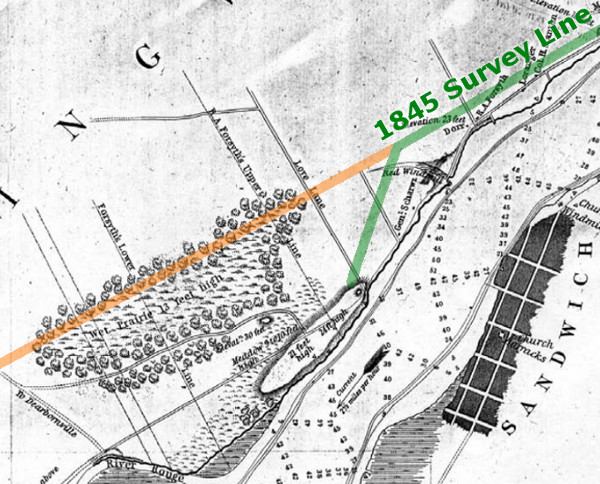

It would be another eight years before the state government succeeded in extending Fort Street, when Governor John S. Barry signed "An Act to revive and extend an act entitled 'an act to extend Fort Street, in the city of Detroit, until it intersects the road leading from the Detroit river to Dearbornville'" on March 19, 1845. John Owen, John Palmer, and James Hanmer were appointed the new commissioners to re-survey the road. However, they did not run a line straight through to Dearborn Street. Instead, they continued the street at the prescribed angle (S 60° W) up to the western edge of Bela Hubbard's farm (about where Hubbard Street is today), then turned to continue at a bearing of S 19° W toward the sand hill where Fort Wayne was under construction. This was probably done to avoid the swampland that lay north of the new fort.

The Detroit Free Press praised the Fort Street extension in an editorial, published September 9, 1845:

We learn that the committee appointed by the act of last winter, to re-locate the line for the extension of this street to the Fort at Springwells, have performed that duty. Several owners of property who formerly made strenuous objections, seem now to be satisfied that the value of their farms is to be greatly enhanced by the projected improvement. This street is already second to none in the city for the airiness and beauty of its site, and its elegant and substantial residences. It is designed to extend the street 100 feet in width, in its present course as near as may be, to the Fort. But a single angle is made, and for almost the whole distance, which is three miles, the road follows a ridge which affords a commanding view of the river.Governor Barry issued a proclamation on December 31, 1845 announcing that the commissioners' report has been accepted, and that he has "proclaim[ed] and declare[d], that said Fort street, as opened and laid out by said Commissioners (as hereinbefore recited and described), has become, and is, and shall remain, a public highway." This state road now extended well into Springwells Township, at least in theory. To bring the road into corporeal existence was another matter.

The Obstructionist

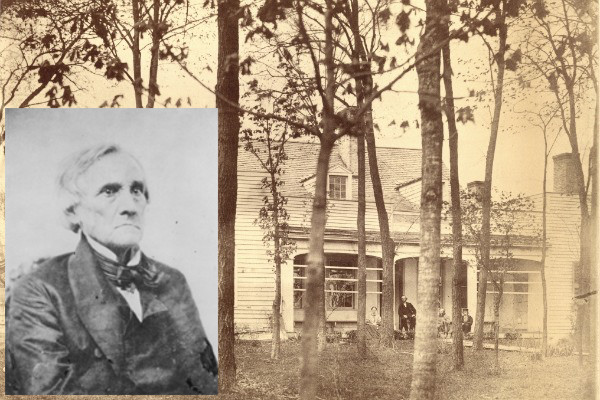

Despite the state's success in legally extending Fort Street, some Springwells residents refused to accept the decision. One of its fiercest opponents was William Woodbridge, former governor and senator from Michigan. The Woodbridge farm was roughly between Eighth and Eleventh Streets, and was the next farm west of the Baker farm, where Fort Street had ended since 1836. Thomas Palmer described the Woodbridge homestead in Early Days in Detroit:

The family residence was a quaint cottage of the villa style...set back quite a distance from the River road, nearly as far back as the present Fort Street. A fine farm the governor had... Beyond and in the rear of the house was a fine orchard, full of apple, pear, peach and plum trees that, it seemed to me, were always in a full bearing mood during the season. I have been in it often, though it had in the front and rear a high board fence to keep out intruders. I got in the regular way.

In 1852, the Springwells Township Board decided to clear and open its portion of Fort Street, which meant destroying part of Governor Woodbridge's valuable orchard. An 1885 obituary for Samuel Ludlow, former township board member, recounts the feud between Ludlow and the ex-governor, who "regularly fenced [Fort Street] across with rails every night for a long time, and Ludlow, as Highway Commissioner, as regularly threw the fences down."

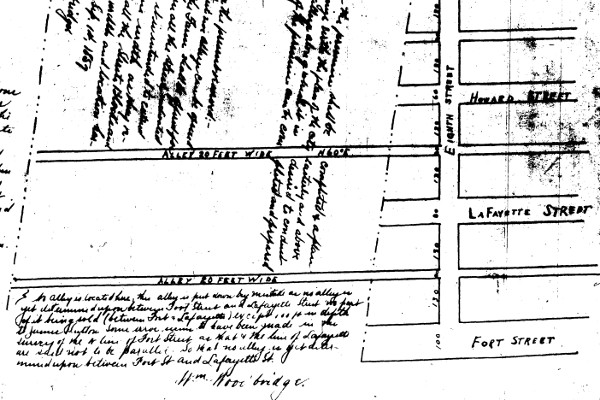

Under instructions from the Township Board he [Ludlow] resolutely chopped down the apple trees that stood upon the line of the street in Gov. Woodbridge's orchard. The latter warned him off and threatened him with personal injury, as well as suit for trespass, but Ludlow was a man of courage and not easily to be intimidated. Gov. Woodbridge sued him, the township backed Ludlow up and at last triumphed. All opposition was withdrawn and Fort street is as you see to-day. Samuel Ludlow, beyond any other man, was instrumental in the opening of that street.And yet this wasn't quite the end of it. By the mid-1850s, the two farms just beyond the Woodbridge estate (the Lognon and Thompson farms) were subdivided. And yet the old governor declined to subdivide his land. On February 5, 1857, the City of Detroit annexed a large swath of Springwells Township, including the Woodbridge farm, extending the city's western border to what is now Twenty-fifth Street. That September, the ex-governor finally submitted a partial subdivision plat, expressly restricted to the opening of four alleys across his farm, and only for the purpose of building water and sewerage infrastructure. Noticeably absent from this plat was any acknowledgement of the existence of Fort Street on his property.

It wasn't until September of 1858, twenty-two years after the neighboring farm was divided into town lots, that Governor Woodbridge finally submitted a subdivision plat showing Fort Street crossing his property, and dedicating the street to the use of the general public.

A Fashionable Residential District

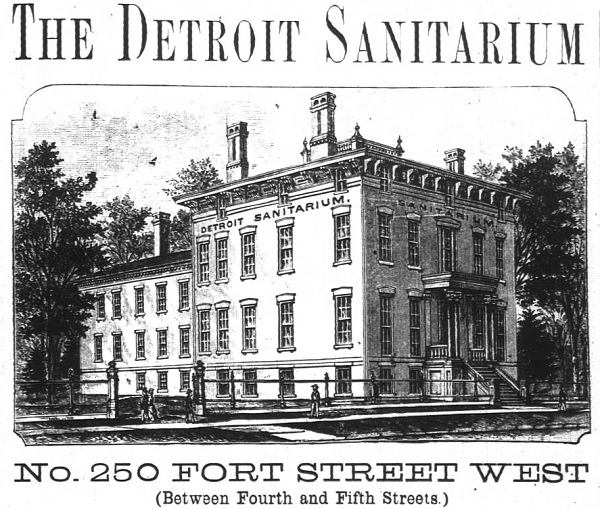

In the days when American cities were cramped and dirty, and before commuting to the suburbs was possible, Detroit's wealthiest citizens built their homes on streets that afforded spaciousness and prominence. East Jefferson Avenue was the first thoroughfare to attract the city's elite in large numbers, but with the growth of the city, commercial buildings came to displace residences there. In the mid-nineteenth century, Fort Street found itself well-suited to become one of the city's most upscale neighborhoods. Only a new, broad and commanding avenue was appropriately scaled for the mansions to be constructed by Detroit's leading politicians and businessmen. A travel guide of the "western" states, published in New York in 1871, noted in its section on Detroit: "West Fort Street is a broad and beautiful street, lined with elegant residences, among which are those of Senator Z[achariah] Chandler, governor Baldwin, James F. Joy, the railroad magnate, and other prominent men."

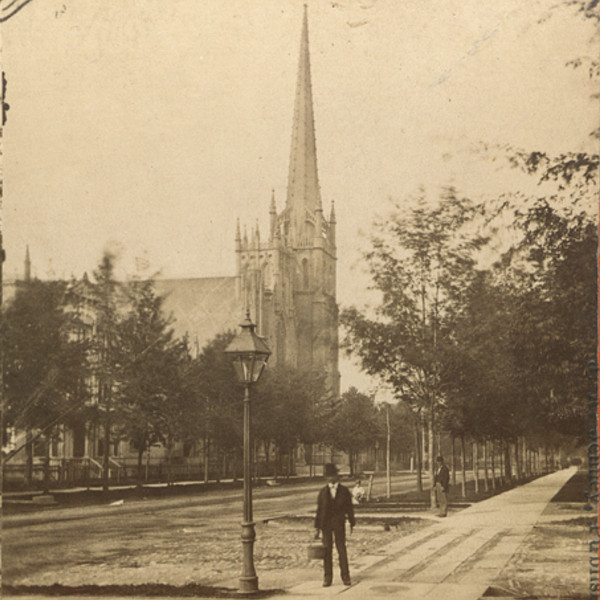

In addition to homes, Fort Street became home to several ornate houses of worship, including the Fort Street Presbyterian Church, completed in 1855, which is still standing today.

Fort Street's status as an exclusive neighborhood was relatively short-lived. By the late 1890s, the city's rapidly expanding business and industrial districts began to encroach on the formerly upscale avenue. Mansions that weren't demolished to make room for commercial buildings were converted to other uses. A story in the December 13, 1896 edition of the Detroit Free Press remarked, "Down Fort street west are many notable old mansions, once the pride of the city; broad, large, hospitable houses, which now are converted into boarding houses, their size recommending them to boarding-house keepers. Where formerly lawns were beautifully kept and the trained gardener looked after the trees and shrubbery, now neglect reigns."

Downriver

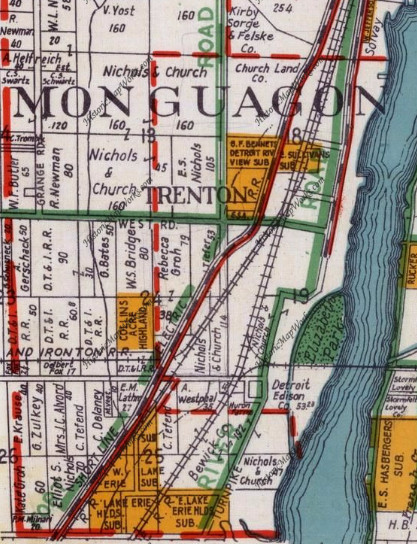

The details of Fort Street's gradual extension beyond the Hubbard farm in the latter half of the nineteenth century are hard to pin down. An 1860 map of Wayne County shows the bend in Fort Street removed, and the road continuing straight to Dearborn Street, but not quite to the Rouge River. The Wayne County Board of Supervisors received petitions to build a bridge over the Rouge River on the projected continuation of Fort Street at least as early as 1868. An 1876 map of Ecorse includes a road that mostly coincides with today's Fort Street. It extends southwest from the Rouge River on the border between two ribbon farms that front that river, making several turns in what is now Lincoln Park, and continuing due south until it dead-ends at what is now Eureka Road.

The Oakwood subdivision, located just west of where Fort Street crosses the Rouge River, was recorded in 1889. The plat labels today's Oakwood Boulevard as "Fort Street Boulevard," and today's Fort Street is simply listed as a "public road."

"A Wider West Fort Street"

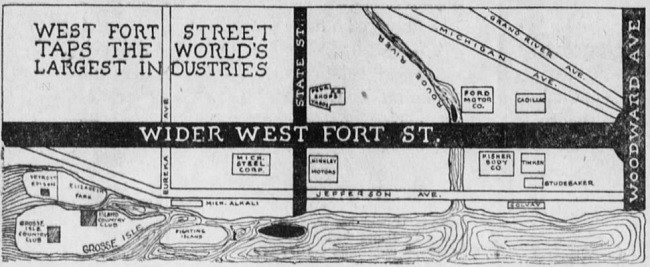

The next leap in the progress of Fort Street began with the Greater West Fort Street Association, whose board of directors included John Ford (a brother of Henry Ford) and real estate dealers Marvin M. Harrison and John M. Welch, Jr. The organization started a campaign in 1923 to straighten, widen, pave, and extend the downriver segment of Fort Street, connecting it with the Dixie Highway. Grade separations at railroad crossings were also supported.

In September 1924, the Detroit Rapid Transit Commission announced that Fort Street had been selected for upgrading into a 204-foot superhighway west of the Rouge River. This "superhighway" was not to be like today's controlled-access expressways, but rather an expansive boulevard with a median that could be reserved for future rail service. Local governments began acquiring the necessary rights-of-way for the project that same year.

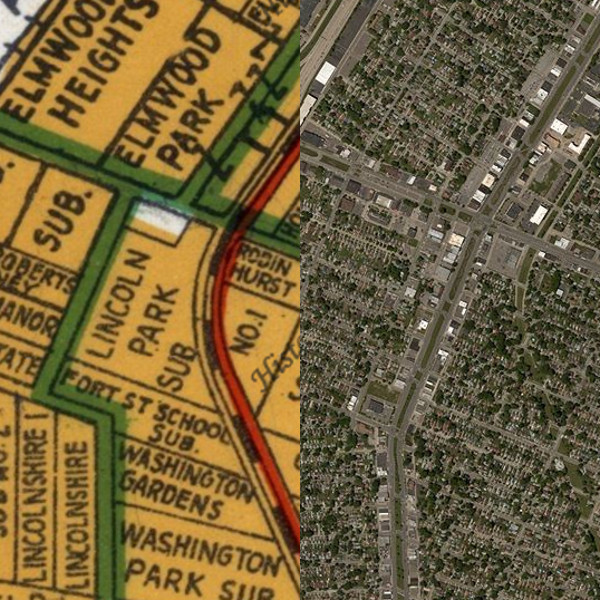

One significant improvement made in Fort Street was the removal of an inconvenient jog that occurred in the Lincoln Park area:

By the mid-1930s, Fort Street had taken the shape that it more or less has today. The road from Griswold Street in downtown Detroit to its connection to I-75 in the City of Rockwood is now identified in the state trunkline highway system as M-85. For a complete history of the M-85 designation, I defer to Chris Bessert's exceptional Michigan Highways site.

Detroit Radials: Conclusion

The popular idea that the city's radial avenues are a product of Augustus Woodward's Plan of Detroit makes for a satisfying narrative about the genius of early urban planning in the metropolitan region. Unfortunately, this concept is flawed at best.

The Woodward Plan is a system for building a pedestrian-oriented city with 200-foot-wide grand avenues heading north, south, east and west, and secondary 120-foot-wide avenues crossing the city at thirty and sixty degree angles. Extending several of these avenues outside of the original boundaries of the city naturally creates "radial" avenues, but this result wasn't necessarily part of Judge Woodward's design. In fact, today's radials are either poor extensions of the core city streets, or not part of the Woodward Plan at all.

- Jefferson Avenue heads east out of the original city limits at the correct angle for about two and a half miles before joining a preexisting shoreline trail, as mandated by an 1821 territorial law. West of the old city limits, the road does not "radiate" on a path prescribed by the Woodward Plan in any way, but more or less follows an Indian trail to Ohio. The first survey of the western route, intended as a military road, occurred in the winter of 1808-1809.

- Woodward Avenue bends to the incorrect angle as soon as it leaves the center of the Grand Circus, due to the way the land north of the original city was surveyed in 1809. The survey of Woodward Avenue's original path between Detroit and Pontiac occurred between 1818-1819 and received federal assistance.

- Michigan Avenue follows the right path for five miles, longer than any other radial avenue--but at the incorrect width. Originally a federal military road, it was first surveyed in 1825.

- Gratiot Avenue does not even begin on the path of a radial avenue, although it does head in the right direction--if only for one and a quarter miles. It then makes a four degree turn, the first of many bends on the way to its original destination, Fort Gratiot. Also a military road, the first survey occurred in 1827.

- Grand River Avenue, like Gratiot, is not placed on the line of a true avenue. Like Woodward, it bends to the wrong angle the moment it leaves the old city boundaries (albeit only by slightly more than one degree). Surveyed in 1832, it was the last US military road to be built out of Detroit.

- Fort Street initially leaves the center of the city at the same angle as two avenues on the Woodward Plan (Adams and Jefferson Avenues), but no avenue at this angle should exist where it does. Unlike the great military radial avenues, Fort Street grew in small sections, first seen on an 1827 city plat, and didn't come close to reaching its present length until the 1920s.

Would've been better off if they could've implemented Woodward Plan 100 years later like D.C. L'Enfant Plan.

ReplyDeleteI'm Абрам Александр a businessman who was able to revive his dying lumbering business through the help of a God sent lender known as Benjamin Lee the Loan Consultant of Le_Meridian Funding Service. Am resident at Yekaterinburg Екатеринбург. Well are you trying to start a business, settle your debt, expand your existing one, need money to purchase supplies. Have you been having problem trying to secure a Good Credit Facility, I want you to know that Le_Meridian Funding Service. Is the right place for you to resolve all your financial problem because am a living testimony and i can't just keep this to myself when others are looking for a way to be financially lifted.. I want you all to contact this God sent lender using the details as stated in other to be a partaker of this great opportunity Email: lfdsloans@lemeridianfds.com OR WhatsApp/Text +1-989-394-3740.

ReplyDeleteI'm glad to have found this - very cool and greatly informative. Possible to contact via email? we are Lincoln Park Museum at lpmuseum@gmail.com Thank you for sharing all this work.

ReplyDelete