This post isn't about streets and borders, but the story of the First Nations' dispossession of this land is a vital part of its history.

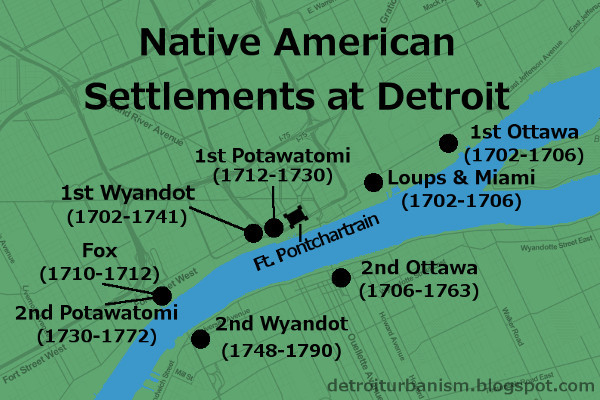

Potawatomi, French, Wyandot (Huron), and Ottawa settlements, circa 1750.

Image courtesy Detroit Historical Society. (Source.)

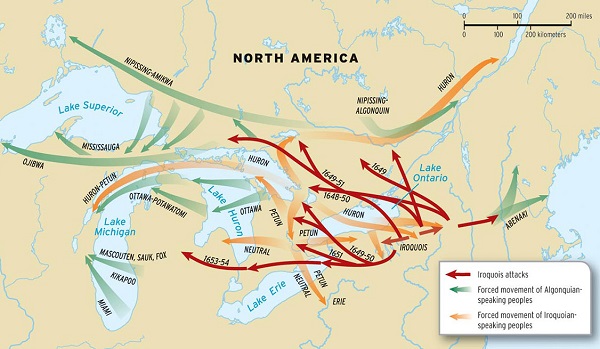

When the French began to explore the Great Lakes at the beginning of the 17th century, southeast Michigan was home to the Fox and Kickapoo nations. Europeans brought with them the disruptive fur trade, instigating the Beaver Wars (1638-1701). The well-armed Iroquois, having exhausted the supply of beaver in upstate New York, conquered the territory to their west, ultimately forcing the Fox and Kickapoo out of Michigan.

For decades, southern Michigan was essentially a no man's land. When LaSalle crossed the lower peninsula on foot in 1680, he found the region to be virtually desolate.

Forced migration by Iroquois Nation during the Beaver Wars.

Image courtesy Oxford University Press. (Source.)

The French Era (1701-1760)

By the time Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac was about to establish Fort Pontchartrain at Detroit in 1701, the Iroquois were losing control of their conquered territory. They were among the forty tribes negotiating the Great Peace of Montreal when Cadillac landed on July 24, 1701. Although Detroit was founded for military and economic reasons, it also had a more Utopian goal: to "bring the tribes together," as Cadillac wrote. He optimistically urged every tribe he could to join the settlement, but the results were not always what was intended.

Map of Detroit in 1702, reportedly drawn by Cadillac himself.

Image courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. (Source.)

In the year after Detroit's founding, bands of Wyandot (Huron), Ottawa, and "Loup" (probably Oppenago) settled close to the French fort. Bands of Miami arrived and lived in a consolidated village with the Loups in 1702 or 1703. In 1706, a fight between the Ottawa and Miami caused the Ottawa to relocate to the opposite side of the river by 1708. The Miami moved to the Maumee River in Ohio around the same time. Chippewa and Mississauga bands arrived in 1703, but built their first joint village at a safe distance from Detroit, at the head of Lake St. Clair.

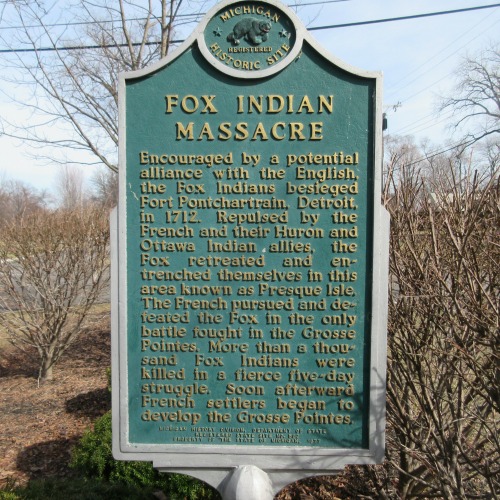

Worse violence erupted after Cadillac invited Fox, Kickapoo, and Mascouten allies from Wisconsin to Detroit. They arrived around 1710, settling near where the Ambassador Bridge meets U.S. soil now. After skirmishes between their allies and the other Detroit tribes, a large group of Fox warriors built a fortified camp just north of Fort Pontchartrain in the spring of 1712. Most of the tribes friendly to the French were still away on their winter hunting trips. The Fox finally attacked the French fort on May 13, 1712, but the Huron and Ottawa hunters soon returned, chasing the Fox back into their encampment. After a two-week siege, the Fox fled. They were pursued to the shores Lake St. Clair where they were cornered and slaughtered. Some escaped, returning to Wisconsin. The Fox, Kickapoo and Mascouten never again settled near Detroit.

Fox Indian Massacre historical marker in Grosse Pointe Park.

Photograph by the author.

The Potawatomi came to Detroit around 1712-1714, temporarily settling in between the Wyandot (Huron) and French forts. As safety and stability returned to Detroit, the Potawatomi gradually moved downstream, establishing their permanent settlement on the site of the old Fox village (the Ambassador Bridge site) at some point before 1732. Chaussegros de Léry's 1749 map of the Detroit River also shows some Potawatomi dwellings at the mouth of the Ecorse River.

Animosity between the Wyandot and the Ottawa in 1738 caused the first tribe to abandon their fortified village and move to Sandusky Bay. The group later split in two, with one faction forming a village on the Canadian shore of the Detroit River just opposite Isle aux Bois Blancs (Boblo Island) in 1742. The Sandusky Wyandots attacked Detroit and burned the Bois Blancs village in 1747. The displaced Wyandots settled closer to Detroit, across the river from the Potawatomi. This arrangement--the Potawatomi and French on the north shore, and the Wyandot and Ottawa on the south--remained stable for fifteen years.

Life in the Villages

The First Nations at Detroit lived on the strait throughout the warmer months of the year, where they raised various crops and traded with the French. Each winter, most or all of a village would camp and hunt in the forests of Michigan and Ohio.

The French population of Detroit grew to 270 within its first decade, but its Native American population was more than four times that. By 1736, there were 580 Native American warriors at Detroit--implying a total population of approximately 2,000. By contrast, Detroit's total white population was a mere 800 as late as 1765.

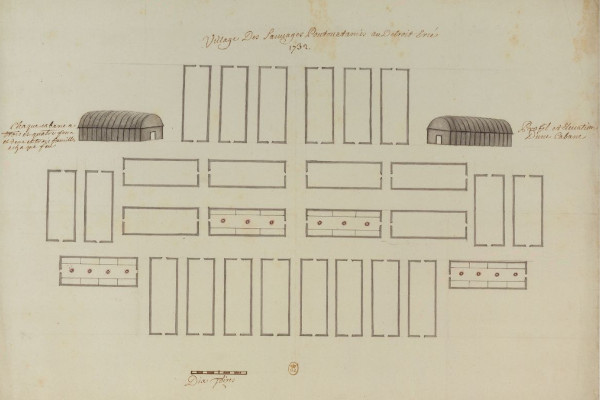

The Potawatomi originally built single-family huts while the Wyandot, an Iroquoin people, constructed longhouses. By the 1730s, observes researcher Brian Leigh Dunnigan, "it would appear that the Ottawa and Potawatomi had accepted the usefulness of the multi-family longhouse, at least for their permanent villages at Detroit, an example of cross-cultural exchange stimulated by the close proximity in which the three Native American groups were living."

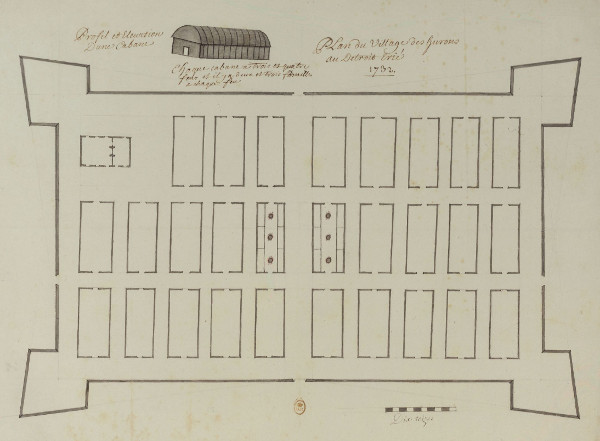

The second Potawatomi village, drawn by Commandant Henri-Louis Deschamps de Boishébert, 1732. The U.S. end of the Ambassador Bridge occupies this space now. (Source.)

The following description of Native American settlements at Detroit is worth quoting at length. When it was written, in 1718, the Wyandot and Potawatomi settlements were just west of Fort Pontchartrain.

The village of the Poutouatamies adjoins the fort; they lodge partly under the Apàquois [huts], which are made of mat grass. The women do all the work. The men belonging to that Nation are well clothed, like our domiciliated Indians at Montreal; their entire occupation is hunting and dress; they make use of a great deal of vermillion, and in winter wear buffalo robes richly painted, and in summer, either blue or red cloth.

They play a good deal at La Crosse in summer, twenty or more on each side... This is fine recreation and worth seeing. They often play village against village; the Poux [Potawatomi] against the Outaouacs [Ottawa] or the Hurons [Wyandot], and lay heavy stakes. Sometimes Frenchmen join in the game with them.

The women cultivate Indian corn, beans, peas, squashes and melons, which come up very fine.... When they go hunting, which is every fall, they carry their Apàquois with them to hut under at night. Every body follows, men, women and children, and winter in the forest and return in the spring.

The Hurons are also near; perhaps the eighth of a league from the French fort. This is the most industrious nation that can be seen. They scarcely ever dance, and are always at work; raise a very large amount of Indian corn, peas, beans; some grow wheat. They construct their huts entirely of bark, very strong and solid; very lofty and very long, and arched like arbors. Their fort is strongly encircled with pickets and bastions, well redoubled, and has strong gates.... The men are always hunting, summer and winter, and the women work. When they go hunting in the fall, a goodly number of them remain to guard the fort....

The soil is very fertile; Indian corn grows to the height of ten or twelve feet; their fields are very clean, and very extensive; not the smallest weed is to be seen in them.

The first Wyandot village, drawn by Commandant Henri-Louis Deschamps de Boishébert, 1732. The Joe Louis Arena parking garage stands here today.

Image courtesy National Library of France. (Source.)

A reconstruction of a Wyandot longhouse in Midland, Ontario.

Image by Flickr user andres musta. (Source.)

The Outaouaes are on the opposite side of the river, over against the French fort; they, likewise, have a picket fort. Their cabins resemble somewhat those of the Hurons. They do not make use of Apàquois except when out hunting; their cabins in this fort are all of bark, but not so clean nor so well made as those of the Hurons. They are well dressed, and very laborious, both in their agriculture and hunting. Their dances, juggleries and games of ball (la crosse) and of the Bowl are the same as those of the Poux...

The Hurons number one hundred men; the Poux, 180; the Outaouaes, about one hundred men and a number of women.

Twelve leagues...up the river, you will find the Misisagué [Mississauga, who lived with the Chippewa] Indians, who occupy a beautiful island where they raise their crops. They are about 60 or 80 men. Their language resembles that of the Outaouae; there is very little difference between them. Their customs are the same, and they are very industrious.

All these Nations construct a great many bark canoes, which is a great assistance to them; they occupy themselves in this sort of work; the women sew the canoes with roots; the men finish and make the [ribs] of these canoes, smoothen and floor (varanguent) them, and the women gum them. It costs some labor to build a canoe; it requires considerable [pains] and preparation, which are curious to behold.

Pontiac's War

The British takeover of Detroit in 1760 was followed by Pontiac's War three years later. Members of all the Detroit tribes supported Pontiac's siege of the fort, which began May 9, 1763. The Ottawas (Pontiac's tribe) encamped east of the British fort at that time. Although Native Americans captured most of the British forts west of the Appalachians, Detroit was never taken, and the siege ended with a truce on October 31.

Native Americans began to distance themselves from the British fort afterwards. The Ottawa were the first to leave, relocating to the Maumee River in Ohio soon after the standoff ended. Pontiac began selling Ottawa property on the Detroit River as early as 1765, when a portion of the land was sold to Alexis Masonville in September of that year.

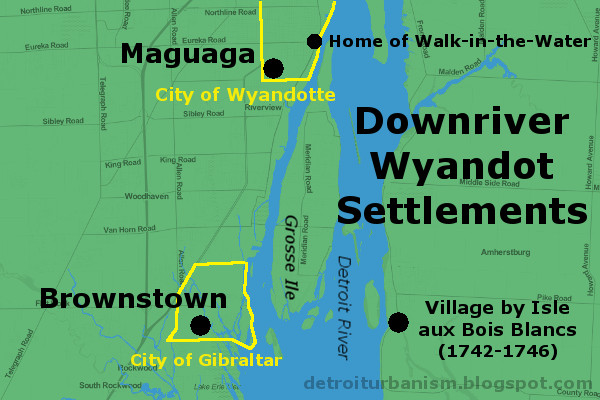

In the following decade, the Wyandot began to move to new villages downriver from Detroit. Maguaga (also spelled Maguagua and Monguagon) was located in what is now the City of Wyandotte. Brownstown, on Brownstown Creek, was named for village chief Adam Brown, a Caucasian who as a child was kidnapped and raised as a Wyandot. Brownstown was also sometimes known as Sindathon's Village.

The Potawatomi also began to leave the Detroit River in the 1770s. They sold their land piecemeal and established new villages farther inland, along the Huron and Rouge Rivers.

One short-lived settlement in Macomb County deserves mentioning. Christian Delaware Indians seeking refuge from American colonists after a brutal massacre in Ohio found safe haven on the Clinton River thanks to Detroit's British commandant and Chippewa guides. They were led by a European-born Moravian preacher, David Zeisberger, and landed on July 22, 1782. They named the new settlement New Gnaddenhütten (Tents of Grace). After barely four years at this location, they departed for a new site in Ontario on April 20, 1786.

Timeline Leading Up to Removal

- 1763—Britain attempts to improve Indian relations, prohibiting colonial settlement west of the Appalachians.

- 1775-1783—Throughout the Revolutionary War, most Native Americans side with the British.

- 1782—In peace negotiations with the United States of America, Great Britain proposes an independent "Indian state" between the Ohio River and the Great Lakes. The U.S. will not even consider the idea.

- 1783—The Treaty of Paris ends the war and cedes the Indian territory to the U.S. No Native Americans were party to the agreement, and they still see the land as theirs.

- 1786—Tribes of this territory form the Western Confederacy and move their Council Fire to Brownstown. They issue a speech to the Continental Congress nullifying land purchases made without their consent and urging the U.S. not to enter their territory.

- 1789—Council Fire moves to Kekionga, present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana.

- 1790—U.S. and Western Confederacy fail to prevent violence between white settlers and native warriors. The U.S. sends 1,450 troops under General Josiah Harmar, who is defeated in every battle with Native Americans and retreats.

- 1791—Major General Arthur St. Clair marches into Indian territory in a disastrous campaign. Of his 920 soldiers, 632 (69%) were killed and 264 were wounded (more than three times the death toll of Custer's defeat at Little Big Horn, where 268 of 647 soldiers were killed). The Western Confederacy loses just twenty-one warriors.

- 1792—George Washington appoints "Mad Anthony" Wayne commander of the United States Army of the Northwest. Blaming past failures on untrained militiamen and inadequate supplies, congress funds a new, professional army under Wayne's direction. He begins building forts in Indian territory.

- August 20, 1794—Wayne confronts the forces of the Western Confederacy and achieves a decisive victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers.

The Battle of Fallen Timbers Monument (1929) by Bruce Saville, depicting

an Indian warrior, General "Mad Anthony" Wayne, and a frontiersman.

Photograph by the author.

Indian Removal (1795-1842)

There is a strange dichotomy in U.S.-Native American policy: Tribes are recognized as sovereign nations whose land titles are undisputed; and yet the U.S. government throughout most of history was resolved to extinguish that title by any means necessary.

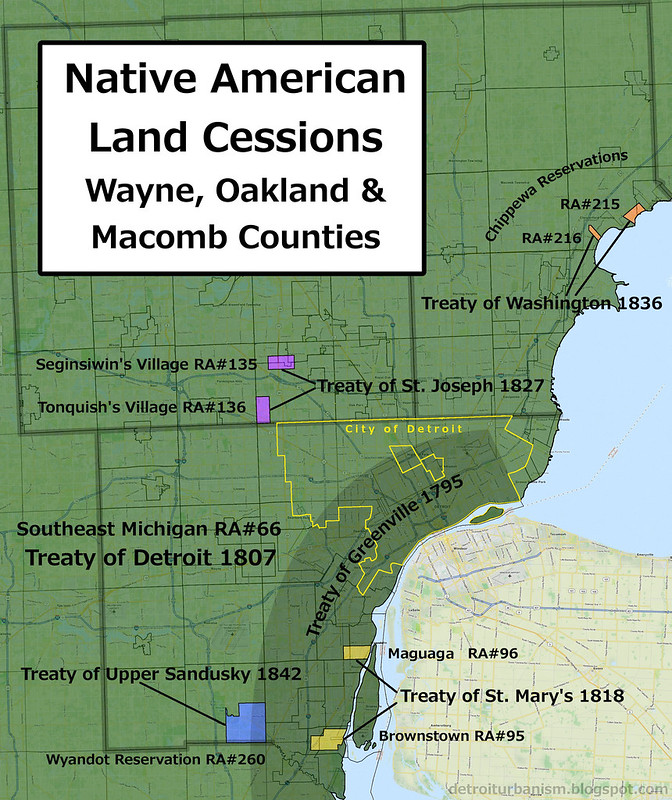

CLICK HERE TO VIEW A LARGER VERSION OF THIS MAP.

What follows are the six treaties and one act of Congress that either granted or extinguished Indian land titles in Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb Counties. Much of this data comes from the research of Charles C. Royce, whose meticulous catalog of land cessions and reservations was published in 1897 for the Eighteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Royce assigned each tract with a number, now referred to as Royce Area (RA) numbers.

Treaty of Greenville (1795)

Signing of the Treaty of Greene Ville, by Howard Chandler Christy.

Miami Chief Little Turtle presents a wampum belt to General Wayne.

Image courtesy OhioHistory.org. (Source.)

In addition to ending the war between the Western Confederacy and the U.S., this treaty ceded to the U.S. most of present-day Ohio and several other areas, including all land within six miles of the Detroit River. The treaty was signed August 3, 1795.

In exchange for ceded land, the U.S. gifted the represented tribes goods valued at $20,000, in addition to gifts valued at $9,500 (divided among twelve tribes) to be delivered every year after that. The tribes also conceded that they were under the "protection" of the U.S. government and no other power.

Treaty of Detroit (1807)

William Hull, Governor of the Michigan Territory, negotiated this treaty with the Ottawa, Potawatomi, Chippewa, and Wyandot Indians of southeast Michigan. The boundary of the ceded lands began at Fort Defiance, Ohio, went due north until reaching a latitude parallel with the mouth of the St. Clair River; from there, northeast to White Rock in Lake Huron, a well-known landmark among Native Americans; from White Rock, south along the coastline to the Maumee River; then up the river back to Fort Defiance. Since this area includes the Treaty of Greenville cession, both are designated RA#66 in the Royce Area numbering system.

The White Rock of Lake Huron.

Photograph by the author.

Excluded from this cession were several reservations, including two Potawatomi reservations in Oakland County and two Chippewa reservations in Macomb County. The treaty permitted the Indians to hunt on the ceded land as long as it remained federal property. The U.S. paid "ten thousand dollars, in money, goods, implements of husbandry, or domestic animals," divided among the four nations, and promised an annuity of $2,400 to all tribes after that. The treaty was signed November 17, 1807. Click here to view the signature page of this treaty.

"An Act for the Relief of Certain Alabama and Wyandot Indians" (1809)

When the Wyandots of Maguaga and Brownstown complained that their settlements were omitted from the reservations of the 1807 Treaty of Detroit, the U.S. Congress passed a law on February 28, 1809 granting them two reservations. They were to coincide with the villages of Maguaga and Brownstown, not to exceed five thousand acres combined. The grant was to expire after fifty years.

The former site of the Wyandot village of Brownstown, once the site of the Western Confederacy's Council Fire. Today the land is a federal wildlife preserve.

Photograph by the author.

It's interesting to note that Brownstown's village chief Adam Brown applied for title to two tracts of land land encompassing his village as private claims in 1808. They were granted to him the following year as Private Claims No. 354 & 355. Brown's adopted son, William Walker, applied for title to two adjacent claims and likewise received them (PC No. 54 in 1807, and PC No. 345 in 1809).

Detail from Plan of Private Claims in Michigan Terr. as Surveyed by Aaron Greeley.

Image courtesy Detroit Historical Society. (Source.)

Included in the image above is the farm of George Bluejacket, PC No. 590, granted in 1808. George Blue Jacket was the son of the Shawnee warrior Chief Blue Jacket, who fought at the Battle of Fallen Timbers and was a signatory of the Treaty of Greenville. The elder Blue Jacket also lived in this area until his death in 1808, but it's not known if he occupied the same farm.

By this time, the Wyandot could no longer support themselves by hunting. They engaged in European farming practices, kept livestock, and built log cabins.

The War of 1812

The dream of Indian independence was revived under the leadership of Shawnee warrior Tecumseh, and the War of 1812 presented an opportunity to ally with Britain against the United States. Tecumseh's men fought near Brownstown and Maguaga before marching on Fort Detroit. The presence of his 600 warriors contributed to its surrender in August 1812. But just one year later, Indian and British soldiers had abandoned Detroit and were being pursued by U.S. forces. Tecumseh was killed when his men stood their ground at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813.

The events at the end of the war echoed the end of the American Revolution: the British had abandoned their Native American allies; in peace negotiations, Britain proposed an Indian state, which the U.S. rejected; and the final peace treaty excluded Native American signatories. The First Nations were technically at war with the U.S. until the Treaty of Springwells in 1815, which more or less put everything back to the way it was before the war, including the observation of previous treaties.

Treaty of St. Mary's (1818)

This treaty with the Wyandots, signed September 20, 1818, terminated the reservations at Brownstown (RA#95) and Maguaga (RA#96). In exchange, the U.S. granted the tribe a 4,996 acre reservation in the southeast corner of Huron Township on the Huron River.

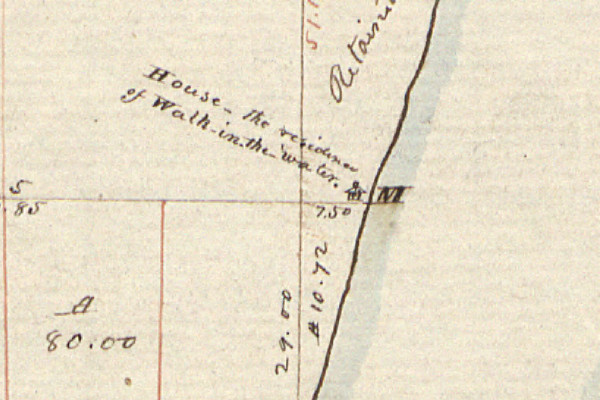

A year before the treaty was signed, the surrounding land was surveyed by Joseph Fletcher. Fletcher's plat marks the location of the cabin owned by the Wyandot Chief Walk-in-the-Water at the village of Maguaga. The cabin was on the Detroit River, just north of where Eureka Road now runs.

Joseph Fletcher, "Plat of Township No. III South, Range No. XI East," (1817).

Image courtesy Bureau of Land Management.

Treaty of St. Joseph (1827)

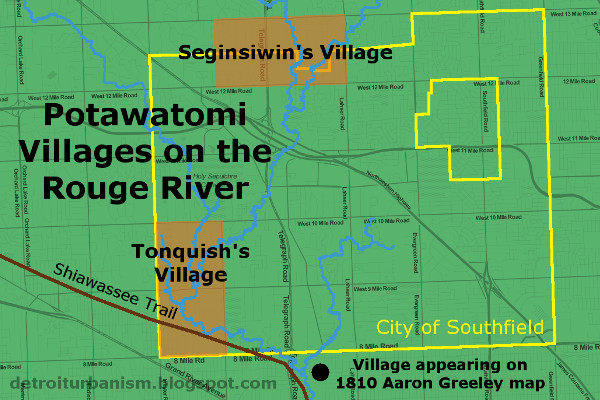

The purpose of this treaty was, as stated in its opening line, "to consolidate some of the dispersed bands of the Potawatamie Tribe in the Territory of Michigan at a point removed from the road leading from Detroit to Chicago, and as far as practicable from the settlements of the Whites." The agreement, signed September 19, 1827, ceded several Michigan reservations including two in present-day Southfield, known as Seginsiwin's Village (RA#135) and Tonquish's Village (RA#136). In exchange, the Potawatomi received a 99-square-mile reservation on the border between St. Joseph and Kalamazoo Counties.

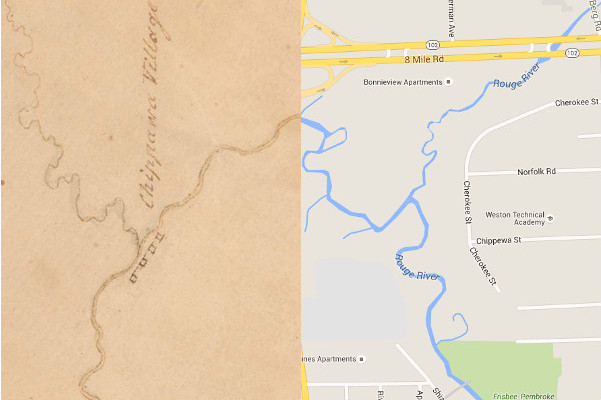

At the bottom of the above image, there was a village that was never part of any reservation. It appears on Aaron Greely's 1810 survey of private claims, labeled "Chippawa Village." This spot is now the Riverford Heights subdivision on Detroit's west side. It contains streets named Chippewa and Cherokee, and used to have Oneida and Ottawa Streets before they were renamed. It is very doubtful that Cherokee or Oneida ever occupied this area.

The Riverford Heights subdivision, Detroit, in 1810 and today.

1810 image courtesy Archives of Michigan. (Source.)

Treaty of Washington (1836)

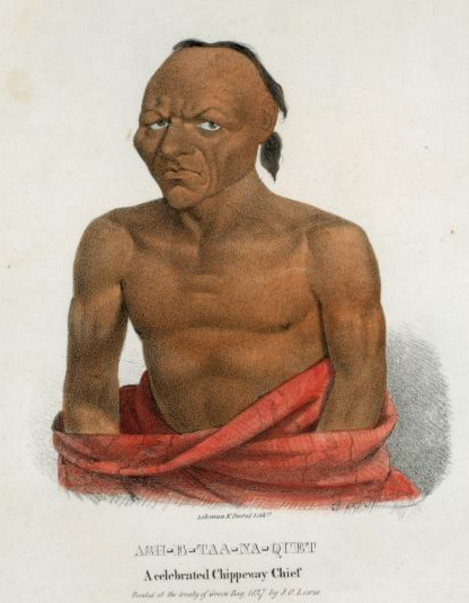

The 1807 Treaty of Detroit created four reservations at the northern end of Lake St. Clair for the Swan Creek and Black River bands of Chippewa Indians. These parcels were ceded by the Treaty of Washington, signed May 9, 1836. Two of them were in present-day St. Clair County, and the other two--the Salt River reserve (RA#215) and Auvase Creek reserve (RA#216)--were in what is now Chesterfield Township. The Auvase Creek site was known as McCoonse's Village. Its chief, Eshtonoquot ("Clear Sky"), was commonly known as Francis McCoonse. According to researcher Steve Brokenclaw, "His Celtic-sounding surname was actually an Anglicized version of his father's Ojibwe name [Macounce]."

Eshtonoquot (Francis McCoonse), a signatory of the Treaty of Washington.

Image courtesy New York Public Library. (Source.)

According to the Treaty of Washington, the U.S. was to sell the four reservations and forward the proceeds to the tribe, minus the costs incurred in the process. The tribe would also receive a new 8,320 acre reservation "west of the Mississippi or northwest of St. Anthony's Falls" that had not yet been located at the time of signing. The sale of the ceded lands took place May-June 1839.

Treaty of Upper Sandusky (1842)

This was the final treaty by which Indian land in Metro Detroit was ceded to the U.S. The Wyandot's Huron Township reservation (RA#260) and another in Ohio were given in exchange for a 148,000 acre reservation west of the Mississippi. The exact location of the new reserve wasn't finalized when the treaty was signed on March 17, 1842. The U.S. would also provide annuities and help defray the costs of moving, providing a school, a blacksmith, and an interpreter. The treaty also relieved the tribe's debt, which had long been used as a tool in obtaining Indian land. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson wrote, "We shall push our trading uses, and be glad to see the good and influential individuals among them [the Indians] run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop them off by a cession of lands."

The Wyandot reservation appears on Orange Risdon's 1826 map of the Michigan Territory (below). Also indicated are the sites of Maguaga, Brownstown, and Blue Jacket's estate.

Orange Risdon, "Map of the surveyed part of the territory of Michigan" (1826).

Image courtesy Saline Area Historical Society. (Source.)

A portion of Metro Detroit's last Native American reservation is now occupied by the 1,756-acre Oakwoods Metropark.

Epilogue: After Detroit

As you take the time to acknowledge the First Nations who once owned this land and fought to protect it, please also remember that these people are not lost shadows of history. No, they're not "extinct." The tribes formerly of Metro Detroit remain active, sovereign, and very much alive.

- The Detroit bands of Ottawa who left in 1763 moved to Ohio. Later treaties moved them to Kansas, and then to Oklahoma, where they live today.

- The Detroit Potawatomi were forced to relocate to Kansas in 1840, but apparently escaped back to Michigan, where they obtained new land and now exist as the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi.

- Although the Black River and Swan Creek Bands of Chippewa had agreed to move in 1836, only Chief McCoonse and a relatively small group actually migrated to their Kansas reservation. Many refused to leave Michigan and simply joined the Saginaw Chippewa, who obtained a reservation in Isabella County in 1855, where they still live.

- The Detroit Wyandots moved to Kansas in 1842, then to Oklahoma in 1855. Their nation remains headquartered in Wyandotte, Oklahoma.

Very good... thanks

ReplyDeleteExcellent research.

ReplyDeleteAlso, the Detroit Public Library's Strom Hall has a mural with a depiction of a Native American event:

The Conspiracy of Pontiac by Gari Melchers

The third mural is Melchers’ depiction of The Conspiracy of Pontiac. 80 years after Cadillac’s arrival the British had assumed control of the region. Pontiac, the leader of several tribes devised a plan to drive them out of the territory. He pretended to offer them peace while he and other chiefs entered the British fort with concealed weapons. The Native Americans intended to take the British fort by surprise and massacre the inhabitants. The British learned of the attack and Pontiac became unnerved and backed out. Melchers illustrated the moment where Pontiac offers a wampum belt to the British Commander surrounded by armed guards.

Just incredible work. Information I've been looking for for a very long time laid out in one place and very well explained. I particularly love the effort at then end to tell us where these groups ended up today. Thanks so much. Definitely bookmarked!

ReplyDeleteThis is excellent research and writing. I've always been curious about the Indian history around the Detroit area and your explanation and maps are very illuminating. Thank you!

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteCancelled Comments????

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteCheck out Queenly for a luxurious and elegant look. If you want to Rent Indian Clothes or looking for Indian Rental Dresses in USA then Queenly is one of the best choices, similar to an Indian rent the runway.

Friends, through this app you can see a map of all the villages.

ReplyDeleteThrough this app, you can see a map of yourself and any other village with the whole district.

From this app you can also see where your village is located in the district.

Download now and enjoy all the services of Village Maps.

All village maps

Gram naksha App

District map App

All City map App

Panchayat naksha Android App

"Loup" is Lenni Lenape / Delaware, without doubt.

ReplyDeleteIn the modern world, living in a township is one of the best alternatives to live a happy life. Thanks for sharing such an informative blog.

ReplyDeleteFlats in Chennai

Luxury Apartments in Chennai

New Apartments in OMR

Hi Paul, Can I get your permission to link to your shot of White Rock for a post I'm doing on the town?

ReplyDeleteCheckout more movies at

ReplyDeleteKrishna and his Leela Full Movie Download Movierulz

Your post was very nicely written. I’ll be back in the future for sure!

ReplyDeletesatta king online

Hey, great blog, but I don’t understand how to add your site in my reader. Can you Help me please?

ReplyDelete토토사이트

Thanks for writing such a good article, I stumbled onto your blog and read a few post. I like your style of writing...

ReplyDeleteAll New Yamaha R25

With so many books and articles coming up to give gateway to make-money-online field and confusing reader even more on the actual way of earning money, Unique Dofollow Backlinks

ReplyDeleteEnjoyed reading this piece, as pre-Michigan history os a favorite, though I believe it is important to detail those who occupied Michigan prior to the Three Fires. The Sauk & the Sioux were both here until defeated and removed by the Three Fires. So in all fairness of historical accuracy, the Chippewa, Potawatomi, and Ottawa bands are not the actual ancestors.

ReplyDeleteMintang Corporate is an agency for visa applications, flight booking, translation and legalization of documents, air and sea freight and company formation in Europe and Africa. Traductions et légalisations

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteAmazing blog! I'm researching ancestry and wanting to understand more than the linear stuff. One piece that's still a mystery... according to the census records, they were born in the 1820s in "St. Francois, Clinton River, Macomb County, Michigan". I've actually found the phrase in several records of the time. Originally I thought it might reference the Auvase or Salt River reserves, but maybe it's (Francis) Macoonse village? Any thoughts?

ReplyDelete