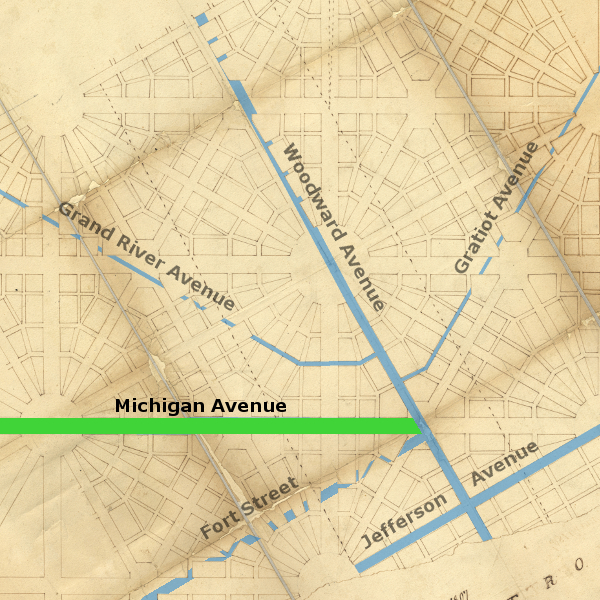

Michigan Avenue was planned as a 263-mile highway connecting Fort Detroit with Fort Dearborn in Chicago, effectively creating a land route between Lake Erie and Lake Michigan. It begins at Detroit's Point of Origin at the center of the city, heads due west for five miles, then falls gently southwest across Michigan's lower peninsula before crossing into northern Indiana and terminating at the City of Chicago. Historically it has been known as the Chicago Road or Chicago Turnpike outside of the Detroit city limits, and today it is known as United States Highway 12. Like Jefferson and Woodward Avenues, its origins are rooted in Augustus B. Woodward's Plan of Detroit, early US Military highways, and centuries-old Native American footpaths.

Michigan Grand Avenue

According to the Woodward Plan, principal avenues that ran north-south or east-west were to be expansive "grand avenues" running 200 feet wide. Washington Boulevard, Madison Avenue, and Cadillac Square are the only surviving examples of this type of thoroughfare. Michigan Avenue was supposed to be one of them. In fact, Cadillac Square is technically an extension of it. But it has never been more than 100 feet wide.

This violation of the Woodward Plan started with the English-built fort that used to lie at what is now the intersection of Fort and Shelby Streets. When the new Plan of Detroit was established, the fort and surrounding property remained in possession of the US Military. The northern border of the so-called "Military Reserve" was the center line of Michigan Avenue. The city gained ownership of the Military Reserve in 1826 and in the following year divided it into a simple gridiron pattern from Larned Street up to Lafayette Avenue. City officials had a plan to completely remove the Woodward Plan and replace it with a rectangular system. When landowners in the city protested, the local government backed off. However, the square blocks in the Military Reserve remained, and the remainder of the land within it--between Lafayette and Michigan Avenues--was divided into lots that came right up to what was supposed to be the center of Michigan Avenue. Ever since then, Michigan Avenue has been only half the width intended by Judge Woodward.

In black: Philu E. Judd's 1824 rendition of the Woodward Plan.

In red: John Mullett's 1830 subdivision of the Military Reserve.

In yellow: Michigan Avenue's original proportions.

The Great Sauk Trail

Before the construction of a military highway, those who traversed Michigan's lower peninsula on foot would have followed Indian trails. One of these was the Great Sauk Trail, which connected the Detroit River to the Rock River in Illinois. This path was sometimes referred to as the Potawatomi Trail, as southern Michigan was then the domain of the Potawatomi. In the 1810s and 1820s, this was the trail taken by thousands of Native Americans from the western territories to Fort Malden, in present-day Amherstburg, Ontario, to receive annuities from the British government for services rendered in the War of 1812.

Source: Spooner, Harry L. The Other End of the Great Sauk Trail.

Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, July, 1936.

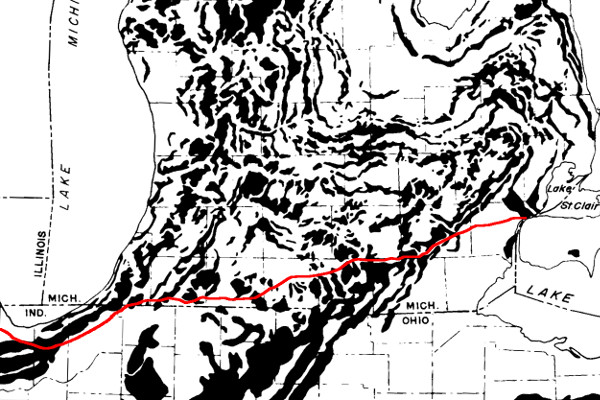

Like many ancient footpaths, topography dictated the location of much of the Great Sauk Trail. The path just west of Detroit was low and swampy, but beyond Ypsilanti the trail was higher, less muddy, and easier to travel because it followed a system of glacial moraines created thousands of years ago.

The Great Sauk trail superimposed over Michigan's moranic systems. (Source.)

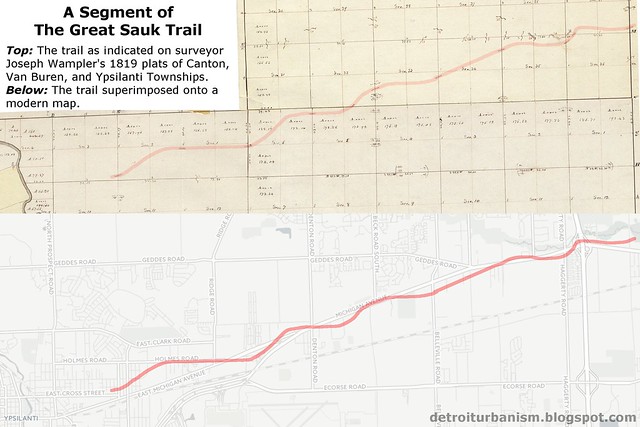

As explained in a previous article, Michigan's Native American trails can be accurately retraced thanks to government land surveys executed before the arrival of white settlers into the state's interior. It is possible to verify that today's Michigan Avenue roughly follows the old footpath.

Unfortunately, not all government surveyors were equally conscientious about recording the locations of Indian paths. Joseph Fletcher, who surveyed the land that includes the present-day cities of Wayne, Inkster, and Dearborn, did not bother to note any paths. However, Joseph Wampler properly recorded their locations in what are now the townships of Canton, Van Buren, and Ypsilanti. Below are details from Wampler's plats of these townships, in which he marked paths with pairs of solid and dotted lines, which have been highlighted here in red. Click on the image to see a full-sized version.

CLICK THE IMAGE TO SEE A LARGER VERSION.

The Chicago Road

Two pivotal events underscored the need for a passable road across Michigan's lower peninsula. The first was the War of 1812, in which Detroit was surrendered partly as a result of inadequate lines of supply and communication. The second was the beginning of federal land sales in the territory in 1818. The Michigan Territory wanted settlers and a road by which they could travel.

The federal government received permission to build the road through Native American territory in the 1821 Treaty of Chicago, which stated, "The United States shall have the privilege of making and using a road through the Indian country, from Detroit and Fort Wayne, respectively, to Chicago." A bill authorizing a survey of the road was introduced in the House of Representatives on April 26, 1824.

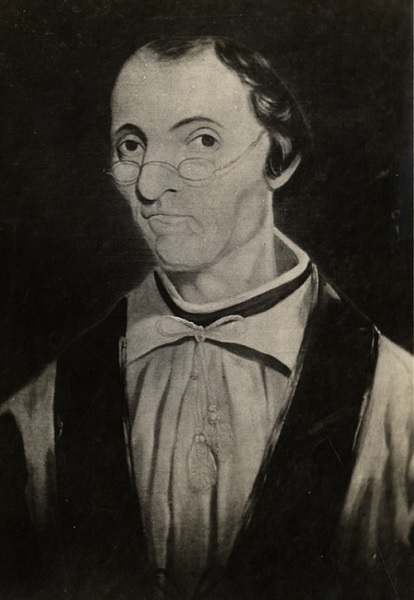

This bill languished for nine months and might never have been passed at all had it not been for the work of the Michigan Territory's congressional representative, Father Gabriel Richard.

Father Gabriel Richard (1767-1832)

Courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. (Source.)

At the time, the Michigan Territory was allowed only a single, non-voting representative in Congress. Father Richard, a Roman Catholic priest and pastor of St. Anne's Church in Detroit, held this position from 1823-1825.

On January 28, 1825, Father Richard delivered a speech before Congress urging progress on the road from Detroit to Chicago.

This road will connect the east of the Union with the west. The grand canal of New York [Erie Canal] will be completed next July. When the said canal is finished, we consider Detroit in contact with New York.Father Richard claimed that the road would "cost less than nothing," arguing that the increase in value of the federal land through which it passed would be greater than the project's expenses. He closed his speech by suggesting that $1,500 be appropriated for the road's survey. However, Representative Daniel P. Cook of Illinois moved that the appropriation be increased to $3,000, which was approved. The House passed the bill three days later, followed by the Senate on February 2. President James Monroe signed the bill into law on March 3, 1825.

In relation to our military operations, the utility of a road across the peninsula of Michigan, from Detroit to Chicago, is obvious. This road will afford a facility to transport munitions of war, provisions, and troops, to Chicago, Green Bay, Prairie du Chien, and St. Peter's River, &c. When our upper lakes are frozen, an easy communication will be constantly kept open, in sleighs, on the snow.

There are more than seventeen millions of acres of, generally, good and fertile land, in Michigan proper... Without a road to go to those lands, they have no value. We are credibly informed, that, on our inland seas, I mean Lakes Erie, St. Clair, Huron, and Michigan, no less than one hundred and fifty vessels are plying up and down, on board of which whole families do come, sometimes, with their wagons, horses, sheep, and milch-cows; land in Detroit, ready to go in search of good land, to settle on it, and having their money ready to give to the Receiver of the Land Office. No road to go into that immense wilderness! What disappointment! ... If there is no road to come to [these lands], who will purchase them?

The Survey

The act of 1825 authorized the President of the United States to "appoint three commissioners, who shall explore, survey, and mark, in the most eligible course, a road from Detroit, in the territory of Michigan, to Chicago, in the state of Illinois." The appointed commissioners were James McCloskey, an experienced surveyor who was then the cashier at the Bank of Michigan; Laurent Durocher, a prominent citizen of Monroe; and Jonah Baldwin, a part-time surveyor from Springfield, Ohio.

McCloskey, as mentioned before, conspired to replace the Woodward Plan with a gridiron pattern in 1808. In 1824, McCloskey signed a petition to the US Senate against the reappointment of Augustus Woodward to the Michigan Supreme Court, falsely accusing him of habitual drunkenness and other trumped-up allegations. Several weeks after McCloskey was made commissioner of the Chicago Road project, he was arrested for, and later convicted of, embezzling $10,300 from the Bank of Michigan.

Although the charges against McCloskey somehow did not affect his commission, it appears that he did not join the survey team on the Chicago Road. The individual credited with being the Chief Surveyor of the project was Orange Risdon, a native of Vermont who began working as a surveyor in Michigan in 1823. Risdon became so familiar with the territory that he wisely purchased land and began a settlement where the Great Sauk Trail crossed the Saline River--a settlement that is now the City of Saline.

Orange Risdon (1786-1876)

Image courtesy Saline Area Historical Society. (Source.)

In addition to Risdon, the survey team included Moses Allen and Musgrove Evans. (Like Risdon, Allen was also impressed with the land along the Indian trail, settling at a spot that is now the Village of Allen.) One pioneer recalled that a chainman on the survey crew was a Frenchman named Mr. Manor. In all, the team probably consisted of six or seven men.

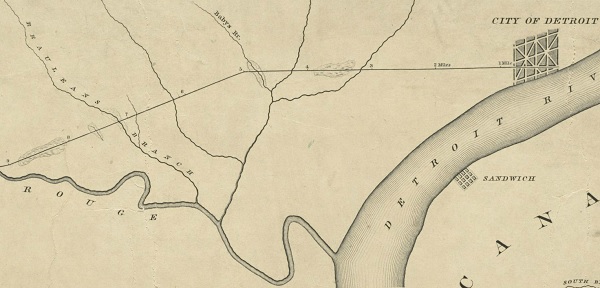

The surveyors started the new road at Judge Woodward's Point of Origin at Campus Martius. According to historian Silas Farmer, their work began on May 24, 1825. They headed west, likely marking their path with wooden posts driven into the earth at each mile. They surveyed a straight line due west for five miles before turning southwest to join the Great Sauk Trail. By doing so, they incorporated Michigan Avenue (which then ended at Cass Avenue) into the new road without violating the Woodward Plan, which had not yet been completely abandoned. Had the Woodward Plan expanded westward, the new road would not have interfered.

The surveying team arrived at Chicago nearly eight weeks later, on July 15, 1825. On July 26, the Detroit Gazette reported:

Road to Chicago.—The Commissioners to lay out this road, and a part of their company, arrived in the schr. Mariner, from Chicago, on Sunday last. The survey was completed on the 15th inst. and they sailed for this place on the following day. The distance form this place to Chicago is 263 miles. Nearly the whole country is represented as delightful, and excellent for a road, excepting a few miles bordering the southern point of Lake Michigan, where sand and sand hills abound.Although McCloskey's field notes have been lost, a beautiful and detailed plat of the survey, made that same year, has survived.

Detail from a survey of the road showing the

first nine miles, from a copy by John Farmer.

Image courtesy Boston Public Library. (Source)

McCloskey sent his report along with the surveyors' field notes and a plat of the route on November 2, 1825. In his report, McCloskey wrote,

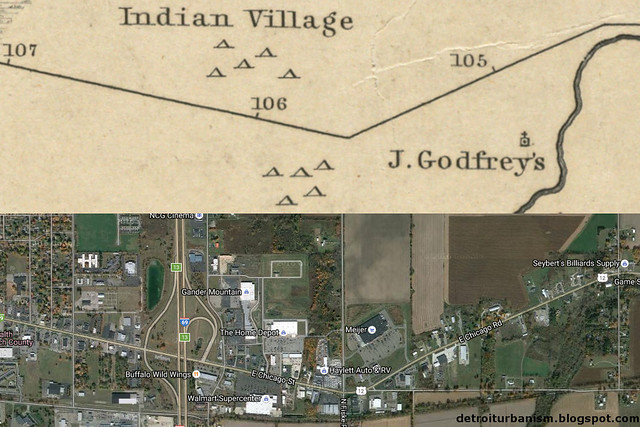

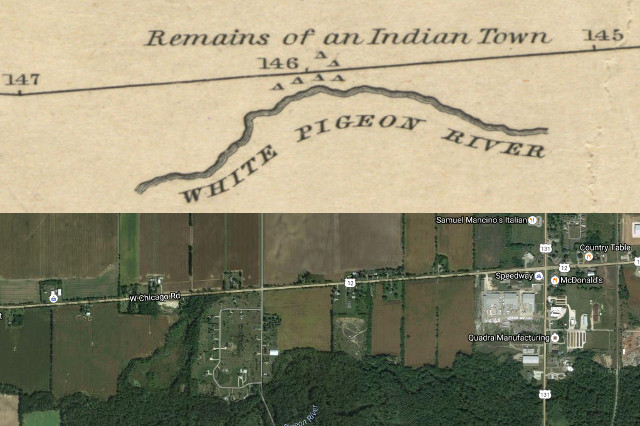

The route taken was an old Indian trail, (so called) which, for aught that is known, has been travelled for centuries, and it is believed, from personal observation of the Commissioners, aided by information from travellers, that a variation of any considerable distance from this trail, would, for the purposes of a good road, be impracticable.A high-resolution, four-page copy of this first plan can be downloaded here. Like the early land surveys, it is a fascinating window into that moment in Michigan's history when the indigenous population's 11,000 year domination was coming to an end, and a massive influx of European-descended settlers was about to begin.

The trading post of Peter & James Godfroy and a Native American settlement on the plat of the Chicago Road line in what is now the City of Coldwater. The village site is now occupied by The Home Depot™ and a Walmart Supercenter™.

A Native American settlement, already vacant by 1825, is noted west of what is now the Village of White Pigeon.

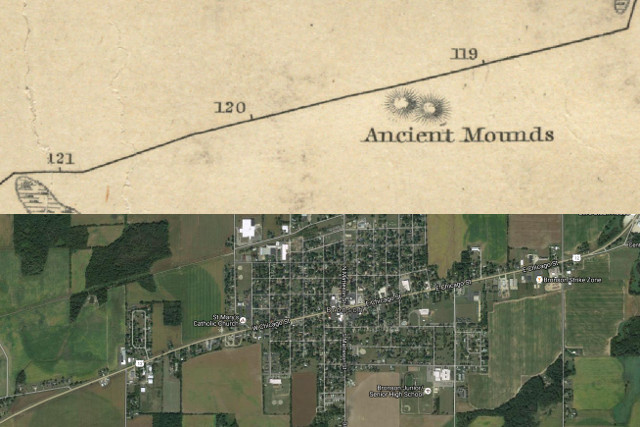

Native American burial mounds noted on the site of what is now the City of Bronson.

In January of 1826, the House Committee on Military Affairs made a report to Congress on the importance of military roads in the Territory of Michigan. The report strongly advocated for appropriations to fund the building of such roads, not just as a means to secure defense against the British, but to facilitate warfare against the First Nations as well.

The committee's report included a lengthy memorial from Michigan Territorial Governor Lewis Cass, who wrote,

A road to Chicago would insure a safe and practicable communication, at all times, with Lake Michigan... A road in this direction would pass through the heart of the Patawatamie [sic] country. The tribe itself is one of the most powerful in this quarter. Upon their friendship little dependance [sic] is the be placed; they were the first to commence hostilities in 1812, and they were the sole perpetrators of the bloody catastorphe [sic] at Chicago. No more important measure for the security of this frontier could be executed, than the construction of a road, which would enable our troops to penetrate into the country at all seasons. It would effectually restrain and overawe them.Regarding the most important highways proposed--the Saginaw, Fort Gratiot, and Chicago Roads, Cass stated,

These three roads, commencing at Detroit, the great depot of the country, passing through the most important parts of the peninsula ... are essential to the security and prosperity of the country. Without them, the forts up on the upper lakes may fall, as they have already fallen: the Indians, removed from the reach of our troops, and feeling confident in their strength, may again descend upon us, as they have before done, and renew the scenes of the Miami and the river Raisin. With these roads, we shall be enabled to penetrate into every portion of the Indian country, to restrain or chastise them, as circumstances may require, and, by operating upon their fears, compel them to become spectators, and not actors, in any future hostilities with a civilized power.

Construction Begins

On March 2, 1827, Congress appropriated $20,000 for the construction of the Chicago Road. It was to be only the first of many appropriations made over time that would complete the road up to the Indiana border. The federal government funded the road only through the Michigan Territory. Indiana, which had been a state since 1816, was responsible for its own portion.

The federal government bid out contracts for quarter mile portions of the road as well as bridges. Private contractors, who were often local farmers, would perform the actual work, which was later inspected and approved by Federally employed engineers. Work was underway by the summer of 1827, but the segment closest to Detroit was not the first to be worked on. The government's number one priority was to build a passable road through the low, swampy area between the Rouge River in Dearborn and the Huron River in Ypsilanti. In all, thirty-three miles were built with the first federal expenditure.

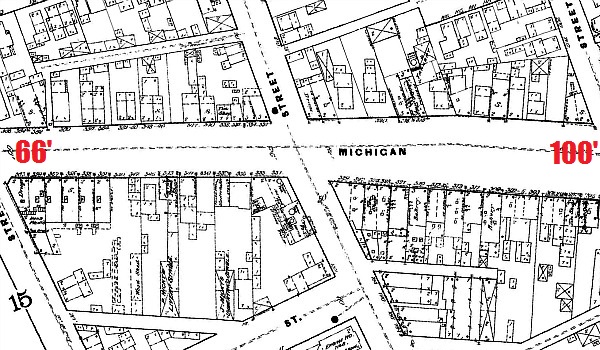

When Congress earmarked an additional $8,000 for the project in May 1828, Governor Cass wrote to Major General Alexander Macomb requesting that some of these funds be used on the road between Detroit and Dearborn. That summer, Governor Cass obtained permission from the owners of the ribbons through which the Michigan Avenue extension would pass. Colonel Daniel Baker, owner of the farm that lay roughly between Brooklyn and Eighth Streets, consented on the condition that the road not exceed eighty feet in width through his land. Later records show that Michigan Avenue was narrowed from 100 feet wide to just sixty-six feet wide just before it entered his farm.

1884 Sanborn Map showing the narrowing of Michigan Ave. between 5th St. and Brooklyn St.

When surveyor Edwin Jerome traveled the road from Detroit to Chicago in October 1831, he recalled coming across "turnpike jobbers, some clearing, some ploughing and scraping, and jobs not yet commenced on the newly laid out Chicago turnpike" near Clinton in Lenawee County. Later that year, Charles Gratiot, Chief Engineer of the US Army, reported that eighty-seven miles had been completed "with some small exceptions," and that "contracts have been made for the construction of 18¼ additional miles, to be finished by the beginning of next May."

Congress made appropriations for the Chicago Road every year from 1827 to 1833, in addition to a final appropriation passed in February 1835 which completed the highway up to the Indiana state line. Just two years later, however, a report to Congress stated that the portion of the road between Detroit and Ypsilanti was "literally worn out" and already in need of extensive repairs.

The Pioneers

Pioneers are often depicted as venturing deep into untouched primeval forests, clearing land to grow their crops. In reality, the first homesteaders in southern Michigan followed well-worn Indian trails to ideal locations previously occupied by Native American settlements. The pioneers planted crops on the same fertile, open prairies--miraculously free of trees and stones--where the Potawatomi had long harvested their own crops. White settlers even occasionally occupied abandoned Indian shelters while building their own cabins. It's no coincidence that settlements such as Coldwater, Bronson, White Pigeon, and Union sprung up on the Great Sauk Trail on the very same spots where previous signs of Native American civilization were noted on the commissioners' plat of the Chicago Road.

The homesteaders of the 1820s and 1830s weren't even the first whites to settle along the trail. French Canadians had already been establishing trading posts on the route for decades. A blacksmith named LaClare settled where the trail crosses the St. Joseph River south of present-day Niles in the late 18th century. Gabriel Godfroy, Francois Pepin, and Romaine LaChambre together founded a trading post at what is now Ypsilanti in 1809. In 1821, Peter and James Godfroy set up their enterprise next to the Native American village at Coldwater.

As increasing numbers of homesteaders poured inland, taverns sprung up along the Chicago Road. These weren't drinking establishments as implied by the modern use of the term, but rather simple inns where migrants could stop for the night, feed their animals, and buy supplies. A popular tavern on the Chicago Road was that of Conrad Ten Eyck in Dearborn, which, being nine miles from Detroit, was about a one-day journey from the city. Other taverns in Metro Detroit include George M. Johnson's place in the present-day City of Wayne, and the inn of Timothy F. Sheldon, which is still standing at 44134 Michigan Avenue in Canton. Among the surviving taverns of Chicago Road farther west are the Walker Tavern in Cambridge Township, and the Clinton Inn, which was relocated to Greenfield Village in the 1920s.

Roy C. Gamble, Pioneers Along the Chicago Road, 1933.

Covered wagons roll through the Irish Hills in Lenawee County as Father Gabriel Richard presents a map of the new road to Native Americans, soon to be dispossessed of their land. Governor Lewis Cass stands nearby.

Photograph by the author.

The following is an excerpt from an account of Abraham Edwards, a pioneer who headed west on the Chicago Road when it was only partially completed:

In the month of August, 1828, I left Detroit with my wife and ten children to seek a home in the western part of Michigan. We commenced our line of travel with three covered wagons which screened the family and our baggage from the weather and also made comfortable sleeping places for our teamsters. We traveled on what was then called the Chicago trail (Indian path) after we left Ypsilanti.

We left Detroit prepared to camp out every night, with provisions, cooking utensils, and a canvas house. The first night from Detroit we slept at Ten Eyck's tavern, at Dearborn; the second night at Sheldon's; and the third night two miles west of Ypsilanti, where for the first time we used our tent and cooked our own meals. From this encampment we left the settlements, except a few scattered squatters on the public lands and Indian trading establishments few and far between, and did not meet a white face for eighteen days, the time spent in traveling from our first encampment to Beardsley's prairie, now called Edwarsburg. Here, on the margin of a beautiful lake and in view of the prairie, finding a log cabin vacant, that had been built by some adventurer and afterward abandoned, we took up our abode and I assure you the first night's rest in that cabin after that long and tedious journey over an almost trackless wilderness was one of the most agreeable in my life. The next morning a wagon was got up to ride out and show the children the prairie. It was then one vast flower garden, and the astonished children were constantly exclaiming as we passed along, oh! how charming, what beautiful flowers!

Roy C. Gamble, Pioneers Along the Chicago Road, 1933. (Detail.)

Photograph by the author.

By the time the road was completed in the mid-1830s, settlers were flooding into Michigan by the thousands, many from the eastern states. The Chicago Road, one historian wrote, was "like an inland extension of the Erie Canal." James Clizbe, who founded the settlement that became the Village of Quincy on the Chicago Road in 1835, later recalled:

You could hardly raise your eyes from the ground, provided you were standing by the side of the Chicago turnpike, but you could see the emigrant wagon covered with white cloth, drawn by a yoke of oxen, the spinning wheel lashed on the rear of the wagon, the father and head of the family walking by the side of the team, the wife and mother sitting in the wagon with her knitting in her hand, and it may be with a babe on her lap, while other children would be trudging along with the father or a little way behind the wagon ; making their way to a home in what was then the far west, Michigan.Many more stories of life on the Chicago Road can be found in the forty-volume set known informally as the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections. Especially interesting are Abraham B. Markham's reminiscence of taking the trail from Detroit to Niles in December 1827, and stories told by William Blackmar, whose family settled on the road in Cambridge Township in 1829 and befriended a Potawatomi Chief, Me-te-au.

Alterations and The Road Today

Although today's Michigan Avenue mostly follows the path surveyed in 1825, many small alterations have been made in the nearly two intervening centuries. One major change occurred just two years after the initial survey. In 1827, Musgrove Evans obtained permission to reroute the road through what is now Clinton Township, Lenawee County. This deviation brought the road several miles closer to Tecumseh, the settlement founded by Evans himself just four years prior.

Back in Detroit, the first three-quarters of a mile of Michigan Avenue is the same as it was in the 1820s, at least in terms of proportion and direction. Beyond that, the right-of-way has been expanded beyond its historic width of sixty-six feet. With the proliferation of the automobile, the City of Detroit widened the road west of Livernois Avenue to 100 feet in the late 1920s. Suburbs along the road followed suit. In 1938, demolitions began in the widening of Michigan Avenue between Fifth Street and Livernois Avenue to the even greater width of 120 feet. Click here to read a complete history of this project in Detroit's Corktown neighborhood.

This building on Michigan Avenue near Sixth Street was demolished in 1939 in order to make room for the widening of the avenue from sixty-six to 120 feet wide.

Image courtesy Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University. (Source.)

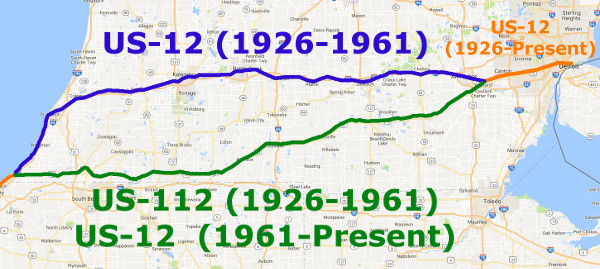

In 1926, the Chicago Road became part of the United States Numbered Highway System. The segment between Detroit and Ypsilanti became part of United State Highway No. 12. This US-12 diverged north at Ypsilanti, and the original Chicago Road beyond this point was considered a "branch" highway and labeled US-112. US-112 followed the old Chicago Road until Milton Township in Cass County. Past that point, the original path had long fallen into disuse, much of it having disappeared altogether. US-112 followed the more well-traveled road northward to Niles, and then headed west to New Buffalo, where it rejoined US-12 on its way to Chicago. By 1961, US-12 had been supplanted by Interstate 94. As a result, the US-12 designation was removed from the northerly route between Ypsilanti and New Buffalo and reassigned to old US-112.

Today, US-12 coincides with the old Chicago Road from Detroit to Milton Township. The original route beyond that is no longer fully traceable, but travelers can still take today's US-12 to Chicago and beyond--all the way to Aberdeen, Washington, in fact. Although I-94 is now the most convenient way to travel between Detroit and Chicago by car, US-12 has become a tourist destination in its own right. In 2004, the Michigan Department of Transportation designated all of US-12 in the state as the US-12 Heritage Trail, and the website USHeritageTrail.org advocates the preservation of the road's history and culture.

Join me on Twitter (@UrbanismDetroit) on Saturday, September 24, 2016, when I will be live-tweeting a trip down the Chicago Road from Detroit to New Buffalo, beginning at 9am!

Great blog! It really brings history to life. Very interesting!

ReplyDeleteGreat blog! It really brings history to life. Very interesting!

ReplyDeleteWow, I always had a feeling that the house you mentioned at 44134 Michigan Avenue in Canton had a history behind it, that it was there back in the stagecoach days. Not just by architectural style, but also by a house's proximity, and positioning in relation to old routes can you discern historical landmarks.

ReplyDeleteThis is incredible work! Thorough and well written. Bibliography?

ReplyDeleteHyperlinks to original sources are included throughout the post. :)

DeleteGreat, great stuff. Thank you!!!

ReplyDeleteBuy eyeglasses and frames online at cheap price. Order your fashion and prescription glasses for men, women and kids from Express Glasses and get 50% off on second pair.

ReplyDeletemens eyeglass frames

best place to buy glasses online

prescription eyeglasses online

best cheap glasses online

Buy eyeglasses and frames online at cheap price. Order your fashion and prescription glasses for men, women and kids from Express Glasses and get 50% off on second pair.

ReplyDeletemens designer eyeglasses

mens designer frames

best online glasses

cheap prescription eyeglasses online

best online eyeglasses

I was looking for a concise history of the Chicago Road, and I found your great blog! Great story. One point: "Gabriel Godfroy, Francois Pepin, and Romaine LaChambre together founded a trading post at what is now Ypsilanti in 1809." - oft repeated, but not quite true. Those dates are when the Detroit Land Board regularized their titles. See this article from the Ypsilanti Historical Society Gleanings: https://aadl.org/ypsigleanings/19581

ReplyDelete