Facing east down Manchester Avenue in 1911, as a Ford factory addition rises in the foreground.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

As we saw in part one of this series, the Village of Highland Park was established in the 1880s with the intention of becoming an exclusive residential suburb with low taxes and constantly rising land values. In order to accomplish this, the village government took on as much debt as it could and levied extremely high assessments for sewer construction and other improvements. Highland Park was headed down the same path as the Village of Saint Clair Heights: ultimately choosing annexation to Detroit when it could no longer function independently. This suburb, however, was about to be saved by a once-in-a-lifetime addition to its tax rolls, thanks to an ambitious Detroit capitalist who was looking to move his business out of the city and build a whole new factory complex up in the suburbs.

Ford to the Rescue

Local inventor Henry Ford in 1904.

(thehenryford.org)

Henry Ford announced in April of 1907 that he had purchased 60 acres up in Highland Park from the estate of Captain William H. Stevens on Woodward Avenue at the Detroit Terminal Railroad. Once the site of Captain Stevens' Highland Park Hotel, a factory of monumental proportions would rise on this spot, growing continuously until it became literally the largest factory on the planet Earth. Ford, 44 at the time, had already been producing automobiles at his Piquette Avenue plant, where a team of engineers were already at work developing "the car of the century." One year later Ford would move his family from their home at Harper and Brush avenues to an architect-designed home at 140 Edison Avenue, on land that had previously been annexed from Highland Park.

Ford's factory under construction, circa 1909.

Ford's factory under construction, circa 1909.(thehenryford.org)

The Oakland Line

Soon after Ford's announcement, the Detroit United Railway (DUR) moved to construct its new storage and repair facilities on a 20-acre tract on Woodward opposite of Ford's factory. The DUR also quickly applied to Highland Park for a streetcar franchise, ostensibly to carry workers to the factory, by extending its existing Oakland Avenue tracks in Detroit northward, through the village, to Lamartine Avenue (now called Manchester Street), then west to Woodward Avenue, before finally turning north toward Palmer Park.

From the November 17, 1916 edition of Electric Railway Service.

(Hathi Trust)

Detroit had a big problem with this. The city's mayor at the time, William B. Thompson, was elected on a platform of getting the DUR to lower streetcar fare to 3¢ anywhere in the city. His plan hinged upon an expired segment of the DUR’s franchise on Woodward Avenue, between the Grand Trunk Railway and Pallister Street. If Highland Park were to grant the Oakland Avenue franchise, the DUR could simply bypass the expired segment in Detroit and continue carrying interurban passengers in and out of the city. When he learned that he could lose his only leverage in the DUR negotiations, Detroit's mayor publicly suggested that the people of Highland Park bring ropes to the village council chamber and drag out any councilmen who vote in favor of granting the DUR permission to use Oakland Avenue. ("Suggests rope for Highland Park trustees." DFP, May 5, 1907.)

The village council nonetheless granted the franchise on May 13, 1907. ("Franchise is passed, ropes are not used." DFP, May 14, 1907.) As part of their agreement with Highland Park, the DUR agreed to pave the northernmost half-mile of Woodward Avenue in the village, which had reportedly not been finished properly by a previous contractor. The DUR's paving job saved the low-tax village an estimated $25,000 ($700,000 today). This would not be the last time that the city and village found themselves as competitors rather than collaborators.

Woodward's Deterioration Sparks Multiple Annexation Attempts

When Highland Park paved Woodward Avenue with asphalt in 1899, the improvement "sent the price of land skyward." ("Paving proposition may fail in Highland Park." DFP, Aug. 12, 1908.) But by 1908, the roadway had become so filled with potholes that "automobilists [had] to pick their way to save their cars from injury." ("City in brief." DFP, Jun. 6, 1908.) Village leaders had a difficult time figuring out how to pay for maintaining a road which was supposed to have been a symbol of the village's economic prosperity. The village council didn't want to raise the general tax rate, which was still only half of what Detroiters were paying. Property owners on Woodward opposed being assessed for the cost, since they were already assessed when the new pavement was first put down, and felt that maintenance and replacement should be covered by general taxation. But raising the tax rate was opposed by everybody except those who owned property on Woodward. Some felt that Detroit should cover part of the cost because they used the road on their way to Palmer Park; Detroiters countered that Highland Park residents enjoyed city amenities including Palmer Park and Belle Isle without contributing taxes for their upkeep.

Annexation to Detroit was discussed as a possible solution. The big city owned its own asphalt plant and could repave Woodward more cheaply than a contractor hired by the village. The prominent real estate dealer William W. Hannan supported the idea, saying that city services which only Detroit could readily supply would be needed for the hundreds of homes that would inevitably spring up around Ford's new factory, still under construction. ("Annex Highland Park village." DFP, Dec. 13, 1908.) Still, many villagers simply wanted to get the top-quality road they wanted as soon as possible, and put off the annexation debate until later. The only solution acceptable to the majority of villagers was to borrow even more money in the form of bonds. If Highland Park were to be annexed, Detroit would automatically take over all of its debt anyway. The Detroit Free Press quoted Clarence S. Prentiss, proprietor of the Highland Park Pharmacy (pictured below), who said: "I would advise the voters of Highland Park to bond and tax to the limit and not come into Detroit for at least two years, till we get the necessary improvements." ("City in brief." DFP, Mar. 1, 1909.)

Prentiss' Highland Park Pharmacy (left) and Smith's Highland Park Grocery (right), located southeast of Woodward and McLean, in 1911.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Before Highland Park had a chance to "bond and tax to the limit," Detroit common council member James Vernor called for annexing both villages of Highland Park and Hamtramck. In February 1909, Vernor asked the council's charter and city legislation committees to draft an annexation bill to send to Lansing. ("Ald. Vernor wants Highland Park annexed." The Detroit Times, Feb. 10, 1909.) Frank Holznagle, once president of the village, publicly endorsed the plan. Highland Park was already $173,000 (≈$5 million today) in debt and voters had just approved a $35,000 (≈$1 million today) bond to construct a new school. Holznagle told The Detroit Times:

"The present plight of the village is due to the lack of foresight of the officials of ten years ago. The village has not a single dollar of sinking fund now. We have no fire protection except such as comes from an agreement with the city for use of the Mott ave. engine. If that engine happened to be out at a city fire when we had a fire in Highland Park, I do not know what would happen."

("Proposal to annex Highland Park causes squabble." The Detroit Times, Feb. 13, 1909.)

Not all villagers agreed, of course. A "Home Rule" party emerged ahead of the March 1909 election, and adopted the slogan "Honesty, economy, necessity and temperance." ("Home Rule party formed." DFP, Feb. 19, 1909.) An unnamed Highland Park resident was quoted by the Free Press saying that the proposal to annex the village to Detroit was only a distraction: "The only real issue in the village election is the selection of village officers, who will give the people a clean, business administration and keep the village free from saloons and make it a wholesome place for women and children to live." ("Plan to deceive voters." DFP, Feb. 21, 1909.) The pending bill was amended to annex Highland Park, Palmer Park, and a small amount of adjacent territory. But when it was sent to Lansing, lawmakers refused to take it up, as they were already working on an entirely new law regarding the annexation process. ("Annexation is up to the cities." DFP, Mar. 9, 1909.)

One version of the 1909 annexation proposal is highlighted on this map from the March 19, 1909 edition of the Detroit Free Press.

(freep.newspapers.com)

With annexation temporarily off the table, Highland Park still needed a way to pay for resurfacing Woodward. "The council," explained village president Edwin Bartlett, "after due and careful consideration came to the conclusion that the most economical and business like way to make this imperfectly necessary improvement was to issue bonds, the payment of which should continue over a period equal to the life of the pavement." ("Defends bonding plan as economy." DFP, May 28, 1909.) This "economical" plan was to issue $72,000 (≈$2.1 million today) in bonds paying 4.5% interest over 15 years, plus a direct tax levy of $20,000. The proposal was made at two special elections on May 12 and 28, but both times it failed to receive the two-thirds of votes necessary to pass.

After months of arguing over who should pay for the new pavement and how, the village council decided in August 1909 to resurface Woodward Avenue with bitulithic pavement at a cost of $116,000, and assess 70% of the cost to adjacent property owners. There was a bitter protest from the people. The Stevens Land Company filed an injunction against the president and clerk of the village from signing the contract, claiming that the job should only cost half as much, and that property tax assessments under the plan would exceed the legal limit, which was capped at a certain percentage of the land's value. The council finally relented, voting that October to simply fill the holes in Woodward, which they admitted was a waste of money.

Meanwhile, just north of Highland Park, the Wayne County Road Commission had just rebuilt Woodward between Six and Seven Mile roads as the first mile of concrete highway in the US. The 18-foot-wide strip of pavement significantly cut down on dust kicked up by the heavy traffic to and from the Michigan State Fairgrounds, one and a half miles beyond the village.

Robert D. Baker, contractor, and George A. Burley, engineer, pose on Woodward Avenue, where work began on the first mile of concrete highway in the US in April 1909.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Soon after the passage of the law updating the annexation process (the Home Rule Cities and Villages Acts of 1909), advocates of a merger between Detroit and Highland Park circulated petitions, according to the new procedure. The petitions were delivered to the Wayne County Board of Supervisors, who in January 1910 ordered a public vote on the question. However, the law said that the election would have to take place within four months, and Detroit didn't have an election scheduled until that fall. The annexation vote would have to wait.

There was no "Pro-annexation party" ticket at the March 1910 village election. There was only a Republican party ticket, which included George L. D. Peterson for president and Royal M. Ford for clerk, among other positions. They ran unopposed and won, as Highland Park was a majority Republican village at the time. The essential points of their election platform were to pave Woodward Avenue as soon as possible (allowing voters to select the type of pavement) and to maintain prohibition within the village limits. (No establishment in Highland Park had legally sold alcohol since the Highland Park Hotel closed around 1906.) The new council had no definite position on annexation, besides letting voters decide. ("Highland Park to have one ticket." DFP, Feb. 17, 1910.)

Clerk Royal M. Ford (left) and President George L. D. Peterson (right) in 1911.

Peterson was a Buena Vista St. resident and manager of the Home Construction Co.

(freep.newspapers.com)

By April, Detroit's mayor, Philip Breitmeyer, told the Highland Park council to go ahead with the repaving of Woodward, as the city's asphalt plant already had two years of work scheduled. ("To learn the cost of paving." DFP, Apr. 2, 1910.) Detroit's Corporation Counsel, Patrick Hally, likewise announced that the city would not object to the village issuing bonds to pay for the project, even if the village was ultimately annexed. ("Pave avenue by issue of bonds." DFP, Apr. 6, 1910.) Woodward Avenue had gotten so bad in the village that the county road commission was recommending that the public take Oakland Avenue to the Michigan State Fairgrounds.

Detroit Free Press, May 15, 1910.

(freep.newspapers.com)

In the village's next attempt to repave Woodward, they placed an $89,000 bond issue question on the April 22, 1910 ballot and published a circular in support of the proposal. "After telling the citizens how badly the pavement is needed," reported the Free Press, "the circular ends with the statement that if the proposition to bond does not carry, the council will cause a 20 mill tax to be spread on the rolls to pay for a pavement." ("Vote on paving bonds." DFP, Apr. 21, 1910.) About half the registered voters went to the polls that day, voting heavily in favor of the bond issue, by 206-39. "The Ford Automobile Co. figured considerably in the large majority," the paper noted. "It had addressed circulars to its workmen the day before, calling their attention to the condition of the street and the need of paving. It also loaned the use of a number of automobiles yesterday which carried voters from the middle of the city and as far north as the Six Mile road to the voting booths." ("Highland Park bonds are voted." DFP, Apr. 23, 1910.)

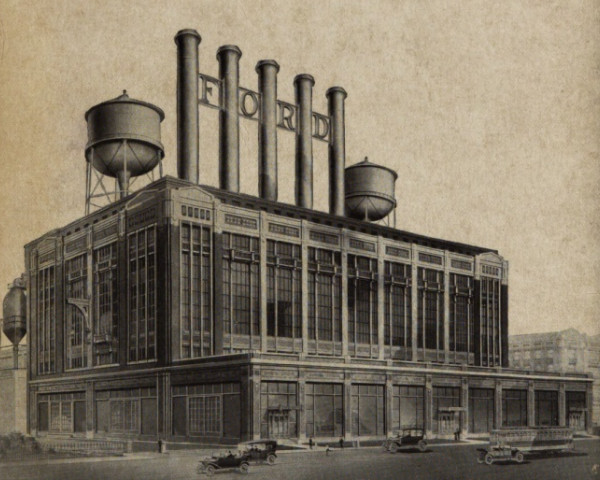

The Ford Motor Co.'s Highland Park factory, which went into operation in January 1910.

The Ford Motor Co.'s Highland Park factory, which went into operation in January 1910.(Shorpy.com)

The council next decided to let the people vote on which type of pavement and which contractor should be chosen among the bids received. "This will relieve the council of all responsibility in the matter," remarked the Free Press. ("Special election called." DFP, May 15, 1910.) There were bids involving a variety of paving materials, ranging from economical options such as bricks, all the way up to the most expensive option, pine blocks pressure-treated with creosote oil.

"The biggest taxpayers in the village do not want either asphalt block or brick," said James Couzens, general manager of the Ford Motor company. "What we want is creosote block and although the low bid for that material is $145,000, we are willing to pay for it [through taxes], and this concern alone pays one-half of all the village taxes. If we are willing to pay half it seems as though the villagers out to be willing to pay the other half. But they wouldn't have to do even that, for many of our officers own land in the village, and the Highland Park State bank, the Highland Park Land Company [of which Henry Ford was part owner] and other large taxpayers feel just as we do about it, that creosote block will prove better and cheaper in the long run."

("Village paving row gets warm." DFP, May 19, 1910.)

The vote took place in a new council chamber constructed at 26 Cottage Grove. Again Ford helped mobilize voters with the five automobiles. (Those who advocated asphalt block had two cars for the same purpose, and the brick supporters provided three.) Ford workers voted early, the Free Press reported, and "every one of them wore a streamer in the button-hole of his coat with the legend 'Creosote' upon it." ("Highland Park votes creosote." DFP, May 20, 1910.) Creosote blocks won the vote with 229 votes, 32 more than asphalt blocks, the second choice. The village council voted on May 23 to award a contract to John A. Mercier, whose bid of $145,101.90 (over $4 million today) was the lowest for creosote blocks. During installation, the Free Press remarked that "the blocks exude a peculiar pungent smell which is quite pleasing to some and most irritating to others." ("Suburban siftings." DFP, Aug. 16, 1910.)

These creosote-laden wooden paving blocks were once part of the pavement on Cass Avenue.

(Detroit Historical Society)

In light of Ford's factory having added several million dollars to the village property tax rolls—and because the job would cost $56,000 more than the paving bonds that had just been approved—the village council reasoned that they could afford to borrow even more. This required another election, held June 10, to approve another $50,000 paving bond issue. Only 58 people showed up to vote, 52 of whom voted in favor of the proposition. ("Highland Park to issue bonds." DFP, Jun. 11, 1910.) Even fewer voters showed up to approve a $31,000 bond issue less than three months later, to pay for water main extensions. It passed by 36-4. ("Villagers vote water extension." DFP, Sep. 2, 1910.)

Detroiters who wanted Highland Park hadn’t given up. In September 1910, a new petition for the merger was submitted to the county board of supervisors. The board ordered the proposal to be placed on the ballot of November 8, setting the stage for yet another bitter contest. Highland Park’s case against annexation focused on two issues: 1) keeping taxes down, and 2) keeping saloons out. Pro-annexationists listed the services they were still lacking—garbage collection, a high school, a police force, fire protection, etc.—which Detroit was already providing for its residents. Not only was the low tax rate unable to fund these services, but it wasn't even sustaining the village's current living standards. All of the village's debt, including school debt and recently approved bond issues, totaled at least $378,000, or about $10.6 million today. A pro-annexation advertisement printed on the day of the election claimed:

The village of Highland Park has done nothing in all its history to pay up its bonded indebtedness, all taxes being used for actual running expenses. If it did the tax rate would be higher than at present. No further improvements can be made without greatly increasing the tax rate of the village, because henceforth a sinking fund must be provided with all bond issues. Thus independence as a village would mean that all additional improvements would raise the tax rate beyond the tax rate of the City of Detroit.

A pro-annexation advertisement from the November 8, 1910 edition of the Detroit Free Press.

A pro-annexation advertisement from the November 8, 1910 edition of the Detroit Free Press.(freep.newspapers.com)

Although a majority of Detroit voters approved the proposal, it failed in Highland Park by 323-291. ("Highland Park will not join." DFP, Nov. 9, 1910.) Two days later, village president George L. D. Peterson victoriously hammered the final creosote block into place in Woodward Avenue, completing the new pavement. "It was with the end in view of securing this improvement for the village that I consented to become a village officer," Peterson said at the occasion, "and now that I have accomplished it, I am satisfied." ("Highland Park's paving finished." DFP, Nov. 12, 1910.) Strangely enough, the cash to do the job came from Detroit, because the city was the purchaser of the $139,000 in paving bonds. The city reasoned that if they eventually annexed the village and took on the debt, they would at least not have to pay interest on it. ("Doremus is given credit." DFP, Jun. 15, 1910. "City's cash box filled." DFP, Jan. 1, 1911.)

Holznagle, the former village president, continued to advocate annexation. He backed yet another such proposal, this one with a guarantee that the village would be a single city ward rather than split up, as many village anti-annexationists feared. ("5,811 want annexation." DFP, Dec. 4, 1910.) However, changing the way Detroit drew ward boundaries was outside the scope of the annexation law, and a lawyer hired by anti-annexationists succeeded in obtaining an injunction against the board of supervisors from considering the petition. More attempts came and went over the years, but none, of course, was successful.

Boomtown

(freep.newspapers.com)

(freep.newspapers.com)When the Ford Motor Company unveiled plans to build in Highland Park in 1907, it appeared to have saved the village from financial ruin. Real estate investors were likewise bailed out by the huge surge in homebuilding activity that immediately followed Ford's announcement. A March 1909 news story describes the building boom taking over the village:

In spite of the fact that it came into official existence twenty years ago, the village grew slowly. There wasn't any inducement for it to do otherwise... [Population] estimates run all the way from 3,000 to 4,000, which is not a bad showing, considering that most of this development has taken place in the last two years. [Emphasis added.]

The transformation wrought in this once peaceful rural community is almost beyond belief. Even those who visit the section frequently are unable to keep pace with the progress being made. The first sound that rouses the inhabitants in the morning is that of hammer and saw, and they are lulled to sleep at night by this same melody. There are streets in plenty where you have to shout to make yourself heard above the din occasioned by carpenters working as though their lives depended on their finishing a house at a given time.

("Highland Park's remarkable growth." DFP, Mar. 7, 1909.)

California St. circa 1911. The home under construction is 26 California.

California St. circa 1911. The home under construction is 26 California.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

A sales booth operated by Judson-Bradway, a major Detroit real estate firm, stands at the corner of Woodward and Richton in this 1911 photograph.

A sales booth operated by Judson-Bradway, a major Detroit real estate firm, stands at the corner of Woodward and Richton in this 1911 photograph.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

A February 19, 1911 Detroit Free Press story paints a flattering picture of Highland Park, calling it "the most modern, cleanest and most progressive village in the state of Michigan." The village to date had laid down 160,000 feet of concrete sidewalks, 30,000 feet of water mains and 40,000 feet of sewer pipes. Within the past year, 316 new houses were built and 28 additional street lights were installed.

Highland Park stands alone among all the other villages in the point of cleanliness. Its streets are models and the residents are required by village ordinance to maintain an appearance about their individual property that would almost rival "spotless town." Not a saloon is included within the boundaries of the village and as one member of the council puts it, "Any attempt on the part of the members of the village council to grant a saloon license would result in their being mobbed."

How was a village with as much debt as Highland Park able to afford these improvements? This article points out that, since 1908, the total value of property assessed for taxes jumped from $4.4 million to $10 million in just three years. Since the borrowing limit of a municipality is a percentage of the taxable value of the properties within it, this meant that even more debt could be taken on. New infrastructure may not require much maintenance at first, and it's easy to forget about replacement cost all together. And since Highland Park was home to some of the largest automobile factories in the world, a handful of big taxpayers were able to cover most of the village's running expenses.

(freep.newspapers.com)

A Growing Industrial District

Beside Ford, other manufacturers were also taking advantage of Highland Park's low taxes and railroad access. The Brush Runabout Company—an automobile manufacturer—built a factory, designed by architectural firm Baxter & O'Dell, in the southeast of portion of the village between 1909-1910.

The Brush Runabout factory in 1911.

The Brush Runabout factory in 1911.(Virtual Motor City)

In 1910, the United States Motor Company purchased Brush Runabout, as well as the Alden-Sampson Commercial Vehicle Company, the Gray Motor Company, the Metzger Motor Car Company, and the Briscoe Manufacturing Company. US Motor purchased land adjacent to the Brush Runabout site, where additional factories for these subsidiaries were constructed. After US Motor went into receivership in 1912, several of these companies became part of the Maxwell Motor Company.

The Alden-Sampson factory in 1911.

The Alden-Sampson factory in 1911.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

The Detroit United Railway’s streetcar storage and repair facilities were a significant part of Highland Park’s industry, as were the several large lumber and coal companies which also set up facilities nearby. Detroit's success as a major industrial center was spilling over into its suburbs.

This 1914 map marks the locations of major supply and manufacturing industries in Highland Park.

(Stephen S. Clark Library, University of Michigan)

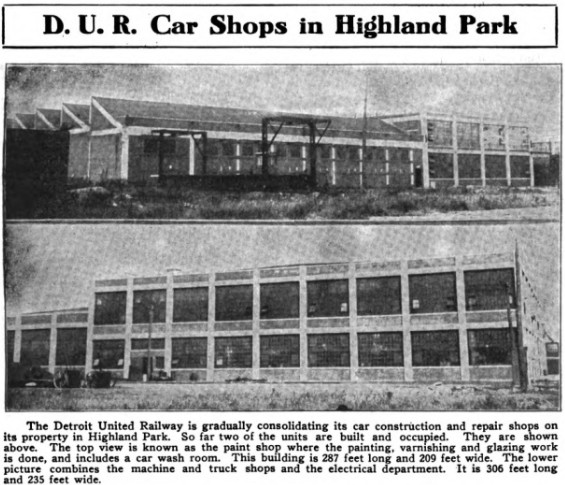

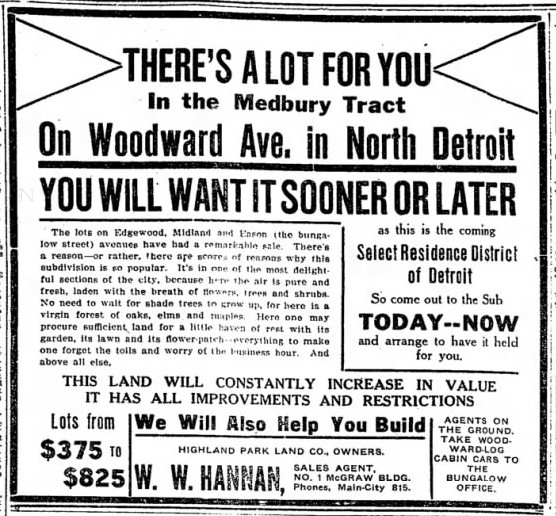

The Medbury Tract

North of the Detroit United Railways site was another new residential development, the Medbury Subdivision. It was held by the Highland Park Land Company, whose owners included Henry Ford, James Couzens, John F. Dodge, Henry E. Dodge, and Joseph L. Hudson. The subdivision was put up for sale in the spring of 1911 because the owners had been "awaiting the completion of lateral sewers, sidewalks and other improvements before placing it on the market." ("Highland Park land to be sold." DFP, Jan. 22, 1911.) The Medbury subdivision was, according to one advertisement,

in one of the most delightful sections of the city, because here the air is pure and fresh, laden with the breath of flowers, trees and shrubs. No need to wait for the shade trees to grow up, for here is a virgin forest of oaks, elms and maples. Here one may procure sufficient land for a little haven of rest with its garden, its lawn and its flower-patch—everything to make one forget the toils and worry of the business hour. And above all else,THIS LAND WILL CONSTANTLY INCREASE IN VALUE (W. W. Hannan advertisement. DFP, Jun. 10, 1911.)

IT HAS ALL IMPROVEMENTS AND RESTRICTIONS

(freep.newspapers.com)

An advertisement from the following year tells us that the Medbury subdivision "abounds in virgin forest," and that buyers "are forever protected against the encroachment of business or the factory." ("W. W. Hannan advertisement. DFP, Aug. 11, 1911.) That November, the just-incorporated Chevrolet Motor Company announced it was going to build a factory on the site, and men were hired to begin chopping down the trees right away.

Detroit Free Press, November 9, 1911.

(freep.newspapers.com)

Ultimately, however, Chevrolet would build their factory in Flint, and this subdivision is in fact mostly residential today.

The Medbury Subdivision's Sylvester Potts bungalow, 70 Eason Street (undated).

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Civic Improvements

Despite the tax revenue coming from several large industries, Highland Park still struggled to deliver satisfactory services to residents. The village council attempted to pave several side streets in 1911, but property owners fought back, claiming that the village's method of assessing the cost was illegal. As more families moved into Highland Park, village schools became overcrowded. Voters approved $55,000 in bonds to construct the George W. Ferris School, which opened to students in October 1911 before the building was even finished in order to relieve overcrowding. When the school opened, of course, it was immediately filled to capacity.

The George W. Ferris School, circa 1915. Demolished in 2022.

The George W. Ferris School, circa 1915. Demolished in 2022.(Virtual Motor City)

One shining symbol of Highland Park's apparent success was the completion of its new municipal building, designed by the Williams Brothers architecture firm (Albert E. and William T. Williams). In addition to housing the village's fire engine—acquired three months prior—the structure also contained office rooms for village officials, a council meeting room, a police station, and a jail. The Highland Park Municipal Building was dedicated on December 23, 1911.

The Highland Park Municipal Building, 20 Gerald Street, in 1911.

The Highland Park Municipal Building, 20 Gerald Street, in 1911.Reconsidering an Independent Water Supply

Although Highland Park's founders originally envisioned their own, separate waterworks, there was no practical way to achieve it in the 1800s. Out of necessity, in late 1896 Highland Park hired Detroit's water board to lay village water mains and connect them to the city’s system. A meter was installed at the city limits and the village charged a rate double what city residents paid. Service was satisfactory at first, but serious water pressure problems developed following years of rapid expansion on both sides of the border. Some homes were reportedly unable to get water on their second floors, and new mains laid down certain streets remained empty because no additional burden could be added. Detroit officials claimed that they were keeping up with increasing demands the best that they could, and that even worse water pressure issues were reported in the western part of the city. By 1913, the Highland Park village council was prepared to investigate alternate sources of municipal water.

Officials didn't have to search far for an expert opinion. Already living in the village at 50 Tuxedo Street was a well-qualified civil and hydraulic engineer named Hans August Evald Conrad von Schon. Born in Germany in 1851, von Schon served in the Prussian Military and earned the Iron Cross fighting in the Franco-Prussian War. He immigrated to the US in 1871, working on engineering projects in several states. After joining the US Corps of Army Engineers in 1893, von Schon went on to supervise the construction of the hydroelectric power plant at Sault Sainte Marie. He even wrote a book and edited a magazine about hydroelectric power. The Highland Park village council hired von Schon in August 1913 to research and design a new waterworks.

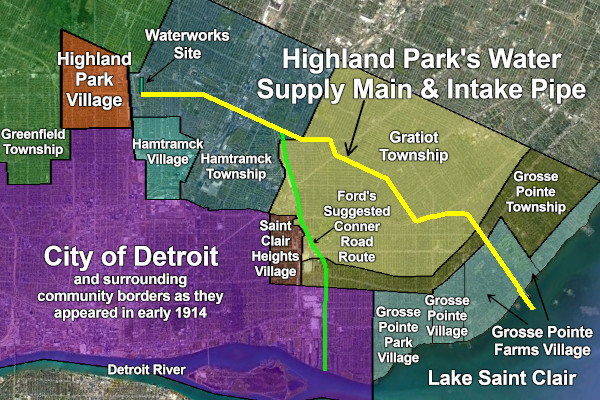

Von Schon made a report to the council at a mass meeting held at the Ferris School on the evening of October 25, 1913. Not only was an independent waterworks possible, but such a system could actually provide better service and cleaner water at a lower cost than what the village was paying for city water. ("Makes report on water situation." DFP, Oct. 26, 1913.) He proposed that the Highland Park's water be drawn from Lake Saint Clair and pumped eleven and a half miles to a reservoir and treatment facility.

In order to finance this massive undertaking, the village council asked voters to approve a $450,000 bond issue at an election held the following month. The realty market responded favorably. "[T]he new water works project is having a beneficial effect on property values and the growth of this district," the H. A. Jones Real Estate company's Highland Park property manager told the Detroit Free Press. ("Suburb continues vigorous growth." DFP, Nov. 2, 1913.) However, on the election of November 8, 1913, although most voters supported the issue (440 to 378), this was below the three-fifths majority required to pass. ("Highland Park votes to bond for new sewer." DFP, Nov. 9, 1913.) The village council got to work preparing to resubmit the proposal at the soonest opportunity.

Twelve Thousand Showed Up!

...Then Got the Fire Hose. In January.

"Crowd of Applicants outside Highland Park Plant after Five Dollar Day Announcement, January 1914"

(The Henry Ford)

As the village council worked on the second waterworks proposal, the Ford Motor Company made an announcement on January 5, 1914, which would trigger the largest population surge in Highland Park's history. Beginning on January 12, in order to curb the company's astronomical 380% turnover rate, wages for male employees over the age of 22 would be increased to $5 per day (or rather the same $2.30 per day, plus a $2.70 potential bonus requiring abstention from alcohol and tobacco, and regular submission to company home inspections). The factory would also transition from running on two, nine-hour shifts to operating continuously on three, eight-hour shifts. According to one account, news that Ford would soon require a third shift of 4,000 workers earning $5 a day immediately caused

a perfect stampede of workmen from every factory [in Detroit] for the Ford plant, and so great did the crowds grow in a short space of time that all of the streets leading to the plant were soon blockaded by a huge crowd of workmen.... Later in the day it became necessary to call out the entire police force of the city to clear the streets so that shipping and the usual activities of the Ford plant could continue.

("Describes scenes at Ford automobile plant." Dayton Daily News, Jan. 8, 1914.)

Although this crowd of local job seekers dispersed, workers from across the region began to arrive in Highland Park early the following morning, lining up at Ford's employment office as early as 3 a.m. By mid-morning, the crowd had swelled to 10,000, which "stormed the plant and were driven away only by the use of clubs and the display of lines of firehose." ("Throngs continue to crowd Ford plant." The Herald-Palladium, Jan. 8, 1914.) Many remained overnight, sleeping on the street and warming themselves near bonfires. The Detroit Times reported that "the entire Highland Park police force was called into action to patrol the walks along Manchester-ave." ("Job hunters still clamor at Ford plant." Jan. 7, 1914.)

"Crowd of job-hunters in front of the Ford factory." Atlanta Georgian, Jan. 13, 1914.

(Library of Congress)

Ford representatives tried repeatedly to tell the crowd that no job offers were actually available at the moment, but to no avail. On January 12, the day the $5 a day wages were supposed to take effect, an agitated crowd of 12,000 applicants who had been waiting in a 9°F blizzard since before daybreak were told that nobody would be hired that day. One police officer at the main entrance attempted to push the crowd back but was knocked down and almost trampled as hundreds rushed inside to get warm. As Ford employees arrived for the morning shift, reported The New York Times,

there was such a congestion that no one could move. The police shouted orders until they were hoarse, but without effect. Then they threatened the crowd with the fire hose, but the crowd would not listen. The job holders kept pressing forward and the job seekers clung to them. Many could not do otherwise because of the enormous pressure on them from behind.

Then the police turned on the water, and employes, job seekers, and police officers themselves were drenched. Scrambling backward the crowd overturned the lunch, cigar, and other stands across Manchester Avenue. Some men, drenched and angry, picked up bricks, stones, and bottles and hurled them at the hose users. Many of these missiles went through the factory windows.

There was no escape for the water-soaked thousands. It was fully fifteen minutes before those in front were able to return and force their way out of reach of the hose. Their garments then were frozen stiff....

The foreign element is blamed for the riot. Much shouting and exhortation in foreign tongues was heard.... It is the belief of the police that a campaign to rush the factory is being organized, and that the foreigners mean to get inside the plant at any cost in the morning, believing that once there they will be put to work.

("Job seekers riot, storm Ford plant." The New York Times, Jan. 13, 1914.)

Neither the Detroit Free Press nor The Detroit Times appear to have reported on this incident.

Clipping from the front page of The Detroit Times, Jan. 12, 1914.

(Library of Congress)

The Creation of the Highland Park Waterworks

Five days after the riot at the Ford plant, a mass meeting was conducted by the village council at Trinity M.E. Church in support of the waterworks bond issue, which was to appear on the ballot for a second time the following week. Experts in attendance assured citizens that a system drawing water from Lake Saint Clair could be built for the proposed $450,000 cost. ("Propose water bond issue." DFP, Jan. 18, 1914.) Henry Ford had even written a letter to village president Donald Thomson in support of the project:

Mr. Donald Thompson: [sic]

I take this opportunity of expressing my appreciation of the efforts of the village council to procure an adequate supply of water for Highland Park. In my opinion, the establishment of an independent waterworks that will furnish an abundance of good pure water direct from Lake St. Clair for domestic and manufacturing purposes will be a great thing for Highland Park now, and in its future growth and development.

Wishing you success, I am,

Yours truly,

HENRY FORD

Although not a Highland Park voter himself, Ford quite openly asked his Highland Park employees to vote for the proposal, estimating that he would provide 400 "yes" votes. At the election held January 24, 1914, more than 70% of voters approved the bond issue, voting 1,151 to 442—well above the three-fifths necessary to pass.

Clippings from the Jan. 17, 1914 and Jan. 25, 1914 editions of the Detroit Free Press.

Soon afterward Highland Park purchased a 20 acre public works site just outside village border. ("Incinerator site is among sales." DFP, Feb 8, 1914.) The property was in what was then still an unincorporated part of Hamtramck Township, located northeast of Davison and Dequindre. By May 1914, Highland Park had contracted with the Detroit construction firm DeLisle & Cooper to build a reservoir and pumphouse at the southern end of this property.

The original configuration of the Highland Park Waterworks and vicinity, from a 1915 Sanborn fire insurance map.

(Library of Congress)

Although there didn't appear to be any controversy around Highland Park building a waterworks in Hamtramck Township, the situation was different when the village purchased land for a pumphouse on Lake Saint Clair in February 1914. The site was on Lake Shore Drive between Moross and Provencal roads in the Village of Grosse Pointe Farms, which even then was an exclusive residential community. Locals were indignant over the detrimental effects a pumphouse would have on their property values and the area's natural beauty, not to mention the inconvenience of tearing up Moross Road for laying the pipe. Grosse Pointe Farms filed suit against Highland Park in Wayne County Circuit Court in April, winning a temporary injunction halting the work until there was an agreement between the villages. Yet there was something peculiar about the public outcry, as engineer von Schon noted: "It is surprising that there should be any objection to Highland Park's plant as it will be erected within 500 feet of the Grosse Pointe Farms pump-house [emphasis added], which is by no means an ornament." ("Highland Park loser in first round in court." The Detroit Times, Apr. 11, 1914.) The dispute would not be resolved for several months.

Lake Shore Drive in Grosse Pointe Farms, near what is now Warner Street, in 1893.

Lake Shore Drive in Grosse Pointe Farms, near what is now Warner Street, in 1893.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

In the meantime, Detroit officials grew increasingly worried about Highland Park borrowing ever more money. It was assumed that annexation of Highland Park was just a matter of time, after which the city would be stuck with all of the village's debt, in addition to an unnecessary second waterworks. Detroit Mayor Oscar Marx invited Highland Park officials to a conference at his office on May 11, 1914 to discuss alternative solutions with members of the Board of Water Commissioners and Department of Public Works. The city discouraged the construction of the Lake Saint Clair pipeline, and instead offered to extend the Russell Street water main for a price of $70,000. This only apparently irritated Highland Park officials, who had been informed by the city, in writing, before the bond election, that no additional water pressure could be provided. President Thomson stated that it was simply too late to turn back at that point, as "the contracts for pipe lines, reservoir and standpipe, have been let." He added, "Besides there is a great deal of complaint in Highland Park against Detroit water, principally because it is doped with hypochlorite." ("City's water supply offer strikes snag." DFP, May 12, 1914.)

Even if Detroit could instantly solve the water pressure problem, Highland Parkers were still unhappy about paying 6¢ per 1,000 cubic feet of water—double what city residents pay—as had been the agreement ever since 1896. The Ford Motor Company, by far Highland Park's largest water consumer, informed Detroit's Board of Water Commissioners in June 1914 that it supported the new waterworks for this reason. ("Council votes approval for subway plans." DFP, Jun. 3, 1914.) Eager to move the project forward, Ford Motor Company officials approached the city with an alternative plan: permit Highland Park to lay its supply main down Conner Road to the Detroit River, rather than all the way to Lake Saint Clair. The company's secretary, Frank L. Klingensmith, and Alfred Lucking, Henry Ford's attorney, sought approval for this plan at a meeting of the city council's committee on streets on June 9, 1914. All committee members appeared to favor the Ford proposal except for one, council member Sherman Littlefield, who insisted that they seek approval from the city's water board first. Klingensmith claimed the alternate route would save $100,000, meaning less debt for Detroit if Highland Park were ever annexed. "Highland Park and Grosse Pointe Farms will sign a contract Wednesday and the matter will be ended unless you act now," Klingensmith threatened. But Littlefield wouldn't budge. "Go ahead and make a contract with Grosse Pointe Farms or any other village you want to. You can't make me think any different." ("Solon blocks Highland Park's water scheme." The Detroit Times, Jun. 9, 1914.) A special meeting was arranged with the water board for the following day, but no Highland Park officials even bothered to show up. The Conner Road alternative was dead. ("Detroit's water offer gets snub in Highland Park." DFP, Jun. 10, 1914.)

Klingensmith may have been exaggerating how soon a contract with Grosse Pointe Farms was ready to be signed, but the Detroit Free Press reported that the villages had negotiated an agreement on the lakeside pumphouse. ("Water system to be finished soon, engineer asserts." DFP, Jun. 18, 1914.) The plan involved using the existing pumphouse at 337 Lake Shore Drive, which the Grosse Pointe Water Works constructed in 1890 to supply water to lakeside homes. That company sold the pumphouse in 1905 to the Peninsular Electric Light Company (later acquired by the Detroit Edison Company), which installed new pumps and continued to maintain the building equipment. But by 1914, the facility had become nearly obsolete. The old 18-inch intake pipe, which ran 1,200 feet out from shore, was no longer considered far enough from shore to reach adequately unpolluted water. Under the new agreement between Highland Park, Grosse Pointe Farms, and Detroit Edison, larger pumps were to be installed in the existing pumphouse, and a new 36-inch cast iron intake pipe would be extended 2,500 feet from shore. The villages paid for the improvements in proportion to their water use (Highland Park's was much higher), and the fees for pumping would be paid to Detroit Edison. The company was to retain ownership of the site for ten years, after which either village would have the opportunity to purchase the property.

Pumping Station at 337 Lake Shore Drive, Grosse Pointe Farms.

(Grosse Pointe Historical Society)

On the evening of June 29, 1914, Hans von Schon submitted his resignation to the Highland Park village council, reportedly due to other obligations. ("Highland Park water works builder quits." DFP, Jun. 30, 1914.) This occurred just one day after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, triggering World War I. Did von Schon, a German native who had served in the Prussian military, foresee the wave of anti-German sentiment that was about to sweep the nation, and decide to stay out of the public eye? Whatever the case may be, the village appointed in his place Lawrence C. Whitsit, hired as a civil engineer earlier that year. Other projects credited to Whitsit include the railroad grade separations on Woodward Avenue, and Highland Park's pedestrian tunnels. Whitsit would ultimately serve Highland Park for 40 years, finally retiring in 1954.

Highland Park Civil Engineer Lawrence C. Whitsit in 1907, and his home at 110 California Street.

(University of Michigan)

With the Grosse Pointe Farms agreement now finished, Highland Park in July progressed with signing contracts for the laying of nearly eleven and a half miles of pipe between the two villages. The job was awarded jointly to three contractors: Joseph P. Rusche Contracting Company (of Grand Rapids), the William Blanck Construction Company, and the Interurban Engineering and Construction Company. ("Pipe contracts awarded." DFP, Jul. 21, 1914.) According to the Free Press, the first three miles of pipe were to be made of cast iron, the middle five miles of wood stave pipe, and the final three miles of reinforced concrete over steel. ("Water system to be finished soon, engineer asserts." DFP, Jun. 18, 1914.) Ford asked the village for a special 8-inch water main running direction from the waterworks to his factory for fire protection, and the village council agreed to lay the pipe "as soon as possible." ("Suburban siftings." DFP, Jul. 29, 1914.)

By September, Highland Park had contracted with the John Henry Baer Construction Company of Port Huron to construct the waterworks intake according to the engineers' specifications. The 36-inch cast iron pipe ran 2,500 feet out into Lake Saint Clair, where a submerged octagonal steel water crib measuring 12 feet across protected the pipe and helped take in water from near the bottom of the lake, away from surface contaminants. The pipe was entrenched and sloped downhill as it went toward the shore, using gravity to draw the water down into a 25-foot deep concrete well located below the pumphouse. From here, five new electrical pumps manufactured by the Manistee Iron Works would supply water to Highland Park and Grosse Pointe Farms.

Detail from a 1921 map of Grosse Pointe Farms raw sewerage discharge points.

(Hathi Trust)

Highland Park's portion of the lake water was pumped into a 30-inch main running northwest, beneath Moross Avenue. After two miles, this main turns southwest along the back boundary lines of several "ribbon farms," tracing the path that is now Chester Street. The main continues below Harper Avenue (then called Derasse Road) before turning onto Whittier Avenue, which at the time was just an unpaved country road.

The path of Highland Park's water intake main through the eastern part of what was then Gratiot Township, superimposed over an 1893 map of the area.

(Library of Congress)

From Whittier Avenue, the main crosses Kelly Road and continues below Houston-Whittier Street, or what was then known as Taylor Road. However, because the paths of Whittier and Houston-Whittier did not originally meet at Kelly, Highland Park purchased just over half an acre of land near the intersection in order to avoid an awkward jog in the water main. The image below shows a modern aerial view of this intersection with "Roney's Super-Highways Subdivision" (1925) superimposed, which indicates the portion of land owned by Highland Park.

The same situation occurred at the next turn in the path at Gratiot Avenue. Houston-Whittier did not align with Westphalia Street within Walter C. Piper's brand new "Gratiot Highlands" subdivision. In order to smooth this bend, Highland Park purchased a 20-foot-wide strip of land from Joseph Droste at the northeast corner of Gratiot and Houston-Whittier in June 1914 for $550. This parcel remains property of Highland Park to this day.

The water main continues beneath McNichols Road and Davison Street to the waterworks site, where the untreated lake water once discharged into a 2,000,000-gallon reservoir.

A cross section of part of the original Highland Park reservoir,

from the April 1914 issue of the Water Chronicle.

(Hathi Trust)

Legal, technical, and financial problems delayed operation of the system for several months. In February 1915 (the same month Henry Ford and his family left Detroit for Dearborn), Highland Park's waterworks superintendent, William G. Patterson, requested an additional $40,000 above what had already been spent in order to finish the job. ("Highland Park to lay 66,000 feet of pipe." DFP, Feb. 19, 1915) The following April, Detroit's Water Board sued Highland Park over the ownership of the pipes that it had installed in the village between 1896-1897. In addition to claiming that the pipes were their own property, the Water Board pointed out that Detroit was supplying water to areas north of Highland Park using the pipes that ran through the village, and alleged that these customers were in danger of being cut off if Highland Park disconnected itself from the city. However, the Wayne County Circuit Court judge found that, according to the 1896 agreement between the two parties, the Water Board was really only acting as a contractor when it built the pipes, and had no right of possession. A three-judge circuit court panel issued a decree that June, vesting Highland Park with full ownership of its water mains, and the village agreed to temporarily supply the city’s northern water customers. ("Village gets sole control of water." DFP, Jun. 12, 1915.) The Water Board would appeal this decision to the Michigan Supreme Court, which ultimately affirmed the earlier decision.

The Highland Park Waterworks was finally, officially put into service on June 28, 1915. ("Highland Park opens its new water works." DFP, Jun. 29, 1915) The water initially delivered to Highland Park water customers was described as "slightly turbid," being unfiltered but sanitized with liquid chlorine.

Excerpt from the Detroit Times, June 12, 1914.

(Library of Congress)

One Thirsty Factory

Hardly a month after the system was put into operation, village engineer Lawrence Whitsit reported that the new waterworks was already inadequate for Highland Park's needs, especially for maintaining adequate pressure for firefighting. The waterworks would have to be expanded, beginning with the purchase of two additional pumps for the Dequindre Street station. ("Highland Park's new water works is not adequate." DFP, Aug. 3, 1915.) According to Whitsit, the two biggest reasons for this unexpected shortfall were: 1) the Detroit water customers temporarily being supplied north of the village; and 2) the Ford Motor Company's new powerhouse, part of a recently announced expansion. When completed in 1916, it was among the largest facilities of its kind in the world. All of Ford's steam, heat, and electricity needs were soon to be provided by the plant's seven gigantic gas-steam engines, whose water requirements alone would be more than double Highland Park's brand new waterworks' maximum output.

The Ford Motor Company's Power House, built between 1915 and 1916 on the spot where Captain Stevens' Highland Park Hotel once stood.

(Hathi Trust)

In January 1916, the Detroit Free Press reported:

Highland Park must increase the capacity of its water plant almost four fold in order to provide the future demands of the Ford Motor company.

Frank L. Klingensmith, secretary of the Ford company, has told the village officials that in the near future the Ford factory will need approximately 30,000,000 gallons of water daily. The present daily capacity of the village water works is approximately 13,000,000 gallons.

According to Don Thomson, Highland Park president, the Ford company's wants for water in the future can readily be supplied, Mr. Thomson said Tuesday.

"We intend to increase the size of the water works equipment to a capacity of 50,000,000 gallons daily. This will provide 20,000,000 gallons for other consumption and ample protection of the village from fire."

("Requires greater supply of water." Jan. 26, 1916)

Interior view of the Ford's powerhouse and its massive gas-steam engines.

(Image via Facebook, originally from Facts from Ford (1920).)

The waterworks began experiencing problems long before Ford's powerhouse went online. Residents were advised to boil their water when the system's chlorinator became inoperable three months after service began. ("'Boil your water' is Highland Park Warning." DFP, Sep. 2, 1915.) In February 1916, needle ice jammed the water intake in Lake Saint Clair, reducing the water pressure from 50 down to 7 pounds per square inch. ("Suburban siftings." DFP, Feb. 3, 1916.) That summer, Dr. John Martin of the Highland Park Health Board informed residents that it would be necessary to boil their drinking water all throughout July, August and September in order to prevent typhoid infection until the waterworks added a filtration plant. ("'Boil water,' says Dr. Martin." The Detroit Times, Aug. 7, 1916.) Warmer weather also meant increased demand, prompting the Highland Park water department to prohibit residents from watering lawns between 7 a.m. and 8 p.m. ("New pumps are nearly ready." The Detroit Times, Jul. 26, 1916.) The system was shut down completely for a day the following autumn, when seaweed churned up by a storm had clogged the intake pipe. "Every store in the town dealing in bottled water was sold out of the fluid by midnight," the Free Press reported. "When it commenced to rain many housewives set out tubs and pails in order to obtain a supply of water for breakfast cooking purposes." ("Water shut off in Highland Park." DFP, Oct. 19, 1916.)

This 1918 advertisement references a recent boil water advisory in Highland Park as a reason to buy Deepspring bottled water.

(freep.newspapers.com)

In order to meet Ford's demands, Highland Park hired William C. Hoad, professor of municipal and sanitary engineering at the University of Michigan, to draw up plans for a filtration plant and a new reinforced concrete reservoir. The reservoir was to have an average depth of 18 feet and measure nearly 300 feet wide by a quarter of a mile long, holding up to 45 million gallons. It was believed to be the largest above-ground concrete reservoirs in the world at the time. On July 10, 1916, voters approved taking on an additional $450,000 in bonded debt in order to pay for these upgrades, in addition to extending water mains within the village. ("Highland Park votes $450,000 new bonds." DFP, Jul. 11, 1916.) Several private contractors bid on the job the following month, but all were rejected on the advice of Professor Hoad, who claimed that the village's own department of public works could complete the job more cheaply. ("Village will build reservoir; $30,000 saved." The Detroit Times, Aug. 26, 1916.) Excavation at the site began that summer.

"[T]he wonderful success of the Ford Motor Co. has created a real estate market that today is perhaps the most active in the United States," reported The Detroit Times of February 5, 1916. "The advance in land values ... occurred simultaneously with the announcement" of Ford's expansion. "The future of real estate values in Highland Park is assured."

(Library of Congress)

"Experiments in Socialism"

Around the time Highland Park was planning the new reservoir, political controversy began growing around Frank Edward Hager, a contractor who had been elected to the village council in 1915. In early 1916 he was called out for privately repeating rumors that Highland Park Police Chief Charles Seymour accepted bribes from certain drinking establishments just outside the village. Chief Seymour demanded an investigation to clear his own name. Although Hager initially denied repeating these rumors, he ultimately issued a written apology to the council and citizens of Highland Park. ("More fireworks follow apology." DFP, Feb. 15, 1916.)

This apparent attempt to embarrass Hager only encouraged others to come forward with accusations against the Highland Park Police. James Isaac Ellmann, a 29 year old Jewish Romanian attorney who had recently moved to the village, filed a complaint with the council, charging Chief Seymour and nine officers with misconduct, against Ellmann himself and several of his clients. Charges included cruel and excessive force, unlawful arrests, denying prisoners counsel and bail, and "indulging in the use of epithets involving race prejudice." ("Seymour once more under fire." The Detroit Times, Aug. 1, 1916.) A formal investigation and hearing before the village council followed, with even the Ford Motor Company lending a helping hand: "Two Ford investigators said that they had come in contact with the village police frequently," the Free Press reported, "and found the treatment of prisoners had always been humane and fair." ("Seymour denies Ellman charges." DFP, Dec. 12, 1916.) The three-member council committee hearing the case (which included Hager) ultimately acquitted Chief Seymour of all charges. Their resolution stated, in part, that "much of the testimony offered to substantiate said charges was given by persons, who, because of their reputation, their criminal records, or their intoxicated condition at the time of their arrest, were not worthy of belief." ("Chief Seymour found not guilty." DFP, Jan. 23, 1917.)

Highland Park Police Chief Charles Wilson Seymour.

(Image courtesy Ancestry.com user Kjanewils.)

When village president Donald Thomson died suddenly in December 1916, Councilman Hager campaigned to fill the final year of Thomson's term at the election of March 1917. His opponent, John L. Austin, accused him of trying to "undermine and destroy the police department," although Hager was part of the committee which acquitted the chief. ("Village campaign centers on police." DFP, Mar. 11, 1917.)

During his campaign, Hager was attacked for his part in establishing a municipal coal yard on Dequindre Road near the waterworks when a particularly severe coal shortage that winter left local dealers without any to sell. The village itself purchased directly from coal yards out east, selling it at cost for home heating purposes to needy Highland Park families. A Detroit Free Press editorial attacked what it called "certain recent experiments by municipalities in socialism," claiming that Highland Park's municipal coal yard lost money and that the public ought to "be wary of the tendency to thrust municipalities into matters which are not properly their concern." (Editorial. "A deficit on the balance sheet." DFP, Mar. 15, 1917.) The Detroit Times, however, praised Hager's efforts as "a step in the right direction" which "must inevitably bring good results to all but the retail coal dealers." ("Highland Park gives bigger Detroit pointers." The Detroit Times, Jan. 2, 1917.)

Highland Park Village President Frank Edward Hager and the home he lived in at the time, 79 Winona Street.

(freep.newspapers.com)

Hager defeated his opponent, Judge John L. Austin, by a mere three votes on March 12, 1917—a lead which increased to four following a recount. ("Hager named village head." DFP, Mar. 20, 1917.) Royal M. Ford, first elected village clerk at age 22 in 1901, lost his first election on that day by just 98 votes. ("Recount ordered in Highland Park." DFP, Mar. 14, 1917.) This election also saw the first socialist party ticket to run in the history of Highland Park, although none of its three candidates were elected.

Once Hager was sworn in as village president, the four-member village council split into factions either supporting or opposing him. On his side were: Frank G. Ladd, who was a general contractor like Hager, and just won his first council race; and Hugh J. McDougall, a Scotch-Canadian cement contractor completing his first year in office. The anti-Hager faction consisted of: attorney William A. Rankin, also newly elected; and Fred J. Caldwell, an accountant for the Cadillac Motor Car Company, who was half way through his second term. One month into his presidency, Hager tried to appoint new heads to the health department and department of public works, citing "inefficiencies." Rankin and Caldwell "refus[ed], after a series of arguments, to back" Hager, according to a Free Press report. "Mr. Caldwell then appealed to the council to keep the departments intact. A crowd in the council room hissed and hooted when he finished. The councilman rose and said: 'Truth cast into the caldron of hell makes just such a sound as that.'" ("Village president has initial clash." DFP, Apr. 10, 1917.)

Concrete for the new reservoir was being poured by that summer. The site, formerly located in Hamtramck Township, had just been officially annexed to Detroit on December 11, 1916. To construct the reservoir walls, large steel forms were built and then filled with concrete from portable mixers, pulled by gasoline-powered engines along tracks temporarily laid on the reservoir floor.

(Hathi Trust)

As another cold, coal-scarce winter approached, the local chamber of commerce petitioned the village council in July 1917 to reestablish the municipal fuel yard. Although local retail coal dealers claimed there shouldn't be any scarcity as there was the previous year, news that federal price controls would not bring down local costs alarmed residents, who urged the village government to repeat last year's program. ("Municipal coal yard demanded." DFP, Aug. 25, 1917.) Following the council's approval of the plan on August 27, the Free Press wrote:

There is to be no aim to make a profit, the village charging only enough to pay expenses of the project. Under this plan the village officials expect to sell coal at much lower price than private dealers. All coal sold by the village must be paid for in advance, and orders can be placed with the official in charge as soon as he is selected, the deliveries to be made at any later date specified. The resolution providing for the municipal coal yard was adopted by a vote of 3 to 2 at the last council meeting. This action ended the fight that has been waged for two weeks in the village council. Councilmen Hager, Ladd and McDougall favored the resolution, while Rankin and Colwell [sic] opposed.

("Village council needs coal buyer." DFP, Aug. 30, 1917.)

Meanwhile, at the reservoir site, work was progressing well enough by September 1917 that the village's superintendent of public works, Harry Hulbert, claimed that construction should be finished in a month. ("Reservoir to hold 40,000,000 gallons." DFP, Sep. 6, 1917.) Other additions to the waterworks, including the filtration plant, would follow.

(Internet Archive)

By October, the municipal coal yard was receiving orders daily, but the village had such difficulty finding a supplier that President Hager was compelled to personally travel to Pennsylvania coal mines in order to secure a shipment for Highland Park. ("Village buys 66 carloads of coal." DFP, Oct. 20, 1917.) The coal was then sold to Highland Park citizens at cost, and strictly limited to families who had no fuel on hand. Orders were filled only after the Highland Park police investigated and certified that the family's coal bin was empty. Before the end of the month, 250 families had benefitted from the program.

At a village council meeting on October 29—the same day the first two car loads of coal arrived at the Dequindre coal yard—councilmen Rankin and Caldwell drew attention to the escalating price of the new reservoir. The lowest bid from a private contractor for the work had been $186,000, yet the village had already spent $374,000 on the project. Engineer Whitsit admitted that there were many unforeseen expenses, but he insisted that the village was still saving money over using a private contractor. Construction costs had been rising across the nation since the beginning of World War I, with sand and gravel doubling in price just between 1916-1917. ("High cost of sand new city problem." DFP, Jan. 23, 1917.) "Mr. Rankin said it was a mistake for the village to go into any business other than running the village," according to one news article. "His motion for an investigation into the reservoir construction costs was lost, and also the motion that the village stop building." ("Council retains reservoir plan." DFP, Aug. 30, 1917.) It was not always clear what exactly the village's "business" was. In June of that year, the council spent $2,000 to buy uniforms for a unit of volunteer "home guards" composed of "business men of Highland Park" to "guard motor plants and help quell possible labor trouble." ("Muster for state troopers Friday. DFP, Jun. 24, 1917. "Highland Park gives $2,000 for home guards' uniforms." DFP, Jun. 26, 1917.)

(Hathi Trust)

On October 30, it was announced that the municipal coal yard would be discontinued and replaced by the newly founded Community Coal Club of Highland Park, consisting of President Hager, councilmen Ladd and McDougall, and Robert C. Siple, vice-president of the American State Bank of Highland Park. Members of the club purchased coal with their own money and sold it at cost on the same terms as the municipal plan, with cooperation of the police and public works departments. Hager told the Free Press that this arrangement was necessary because Rankin and Caldwell were deliberately obstructing the plan. ("Club to replace Park's coal yard." DFP, Oct. 31, 1917.) Hager's efforts were practically vindicated by the severity of the local coal shortage that winter. Reports from the time suggest that no effort to provide families with more heat that winter would have been wasted.

Clippings from the Dec. 15, 1917 and Feb. 6, 1918 editions of the Detroit Free Press.

The Spring Election of 1918

When Hager's year as president was almost up, he filed to run for a full term at the April 1, 1918 election. However, there were many in Highland Park who did not appreciate his way of running things. The previous November, the Free Press quoted Highland Park Justice Edward Bendelow, complaining about Hager's Community Coal Club that "the whole thing is plainly illegal." ("Bendelow wants coal club probe." DFP, Nov. 6, 1917.) Two weeks ahead of the general election, the Highland Park Civic League came forward with the results of a private investigation into the Hager administration, charging extravagant spending, as well as claims that Councilman Ladd's teamsters were doing work for the village and forwarding the checks to Ladd, in violation of the village charter. ("Highland Park quiz demanded." DFP, Mar. 15, 1918.) Justice John Marshall and John L. Austin—Hager's opponent in the 1917 election—asked Wayne County Prosecutor Charles Jasnowski for a grand jury investigation. Jasnowski agreed, and assigned Justice Bendelow to preside at the hearings(!). ("Inquiry approved for Highland Park." DFP, Mar. 17, 1918.) Hager wrote to the county prosecutor, pledging to cooperate, but also imploring him for a swift investigation, calling the situation a "political trick" initiated by "parties who are opposed to my candidacy." He added:

[T]he treachery of the move is so obvious that I feel justified in requesting that you make every effort possible to see that the investigation is expedited so as to give the people of Highland Park a final report before election day, April 1, if possible. I think that in making this request I am asking only justice, and wish to assure you that if there is anything I can do to assist your office I am at your service to command."

("Village president welcomes probe." DFP, Mar. 20, 1918.)

On March 28—four days before the election and three weeks before the end of the grand jury inquiry—Henry Ford released a statement addressed to Highland Park voters, based on the findings of his own investigators. "Heretofore, the Ford Motor company has taken no part in the political issues before the village," Ford's statement began, before reminding voters that 58% of Highland Park's tax revenue was paid by his company. This, according to Ford, was "sufficient to justify our interest to the extent of bringing to your attention certain facts ... which may aid you in determining whether or not the present administration has used proper judgment in directing the affairs of the village." ("Ford company warns voters." DFP, Mar. 29, 1918.) Ford's statement focused on the following points:

- Voters approved a $250,000 bond issue for a public hospital in late 1916, after which the council purchased a five-acre site on the western end of the village for $135,540.18, "leaving $114,459.82 to build and equip a hospital." (This hospital in actuality would cost something closer to $700,000 by the time it finally opened in 1920.)

- As the Civic League had pointed out, checks totaling $7,149.48 for village work were found to have been endorsed by Councilman Ladd. It was against the charter for officials to financially benefit from village contracts.

- The village's department of public works paved 20 streets and 13 alleys in 1917 for approximately $64,000 less than the lowest bids received from private contractors. The problem was that the private bids were used to determine the tax assessments, technically making an illegal profit for the village. Both Hager and his opponent in this election would pledge to refund this amount to the taxpayers.

- Despite winning a drawn-out legal fight with Detroit for the right to increase its connectivity with the city's sewer system—and spending a large amount of money in the process—the western part of Highland Park still experienced flooding problems.

- The new reservoir had already cost nearly $50,000 more than the lowest private bid on the job, which was rejected because of the belief that the village could do the work more cheaply itself. In justifying the costs, the engineer and superintendent of public works reported in part that "the increased cost of sand alone represents an additional cost of approximately $10,000"—yet, Ford claimed, their report also showed that not even $9,000 had been spent on sand in total.

Ford's statement—which never mentions Hager's name—concluded:

We consequently believe it is to the interest of every citizen to carefully consider the questions confronting the village and give proper expression of their wishes at the polls next Monday, April 1.

FORD MOTOR COMPANY.

Henry Ford, President.

At the top of the "anti-administration" ticket was Royal M. Ford, who at the last general election experienced the first electoral defeat in his 16 year career as village clerk. He was not a close relation of Henry Ford, but was a grandson of English immigrant George Ford, one of the first white settlers in the area. At the time the 38 year old bachelor lived with his mother, Josephine (Trombly) Ford, at 13945 Woodward Avenue.

Royal Milton Ford

(Find a Grave)

Following the April 1, 1918 election, the Free Press stated that "the anti-administration forces made a clean sweep in every precinct after the most bitter political fight in the municipality's history." Ladd and McDougall failed to retain their seats on the council. "R. Milton Ford, who had the Ford Motor company's support, had a margin of only 283 votes for victory in the mayoralty contest with Frank E. Hager." ("283 votes give Ford victory." DFP, Apr. 3, 1918.) Of the 3,055 ballots cast for mayor that day, 1,386 were for Hager, and 1,669 were for Ford.

Henry Ford in his office at his Highland Park headquarters.

(Getty Images)

Despite Hager's plea for a speedy grand jury investigation, hearings did not officially begin until two days after the election. The witnesses who were called to testify ranged from a foreman who worked on the reservoir to the chief executive of the Braun Lumber Company. ("Old officials get grand jury call." DFP, Apr. 6, 1918.) Following two weeks of investigation led by assistant county prosecutor Paul Voorhies, it was announced that no criminal charges would be brought against Hager, Ladd, or McDougall after all. ("No indictments in suburb probe." DFP, Apr. 18, 1918.) The high cost of the reservoir had less to do with corruption and graft, and more to do with escalating wartime building costs. "[E]xcessive unanticipated expenditures" in building the reservoir were reported when Donald Thomson was still alive, months before Hager became president. ("Village may lose on reservoir job." DFP, Oct. 10, 1916.) Thomson's bio in Clarence M. Burton's History of Wayne County and the City of Detroit, Michigan claims that Highland Park's performing its own construction work beginning during his administration "resulted in an immense saving to the taxpayers of Highland Park."

Besides the Hager controversy, the April 1918 election was notable in other ways. James Isaac Ellmann, the attorney who had filed complaints against the village police chief, was elected associate justice of Highland Park by a margin of only 26 votes. ("Recount sustains Ellman's election." DFP, Apr. 6, 1918.) That same day, voters also approved the first city charter of Highland Park, one of the final steps in the process of becoming a fully independent municipality.

How Highland Park Became a City

Highland Park was an anomaly among villages in Michigan history. Unlike most villages throughout the state, Highland Park contained the largest factory on the planet Earth. The population surge following Ford's worldwide publicity in 1914 compelled the village council to request a special recount from the US Census Bureau. By November 1915, the municipality of 4,120 had gained an additional 23,050 residents in just five years and seven months—a growth of 559.5%. (To put that into perspective, the most populous village in Michigan today—Beverly Hills, Oakland County—contains fewer than 11,000 residents.)

Why did Highland Park remain a village for so long? And what finally compelled it to become a city when it did? The answers have less to do with taxation or annexation, and everything to do with booze. The village had been without a public drinking establishment since the Highland Park Hotel closed around 1906, and the dominant culture of Highland Park at the time grew increasingly sympathetic with the Temperance movement. ("Goes on record for prohibition." DFP, Oct. 10, 1916.) Highland Park wanted to remain a village because, under Michigan law, the village form of government offered far greater discretionary powers to deny liquor licenses than cities. ("Oppose plan to organize as city." DFP, Mar. 7, 1916.)

This Detroit Historical Society photo, labeled "5 Mile Bar - Woodward - Highland Pk. About 1905-10," could be from the Highland Park Hotel, which had a liquor license and was built on the site of the Five Mile House. This may have been the last legal drinking establishment in the Village of Highland Park.

This Detroit Historical Society photo, labeled "5 Mile Bar - Woodward - Highland Pk. About 1905-10," could be from the Highland Park Hotel, which had a liquor license and was built on the site of the Five Mile House. This may have been the last legal drinking establishment in the Village of Highland Park.(Detroit Historical Society)

Highland Park's preference for village government came to an end following the election of November 6, 1916. On that day, a majority of Michigan voters approved a constitutional amendment prohibiting the sale of alcohol statewide, set to take effect May 1, 1918—after which Highland Park's justification for shunning cityhood would be moot. (Nationwide prohibition would follow two years later.) But there was another reason for the change in opinion. That same election had reportedly witnessed "by far the heaviest voting in the history of Detroit." ("10,000 disfranchised [sic] by Detroit vote muddle." DFP, Nov. 8, 1916.) The heavier than usual turnout was particularly stressful in Highland Park, which did not manage its own elections. Under Michigan law, villages remain part of their townships, and the township continue carrying out certain functions, such as collecting taxes and running elections. The Village of Highland Park had always been part of Greenfield and Hamtramck townships, which were now struggling to serve a village of now more than 27,000 people.

Less than two weeks before the November 1916 election, overwhelmed Hamtramck Township clerks worried that may not be able to serve the vast volume of newly registered Highland Park voters. ("Registration for Hamtramck big." DFP, Oct. 28, 1916.) The election was managed so badly that more than 2,000 voters were observed standing in line outside of a Gerald Avenue polling location that day. A week later, "50 of the most prominent citizens in Highland Park sent communications to the council urging incorporation as a city," being "angered" that "they were forced to stand in line at the polls for hours on election day." ("Suburban citizens urge annexation." DFP, Nov. 14, 1916.) Complicating matters were several Detroit annexations approved by voters that same day, which cut off the villages of Highland Park and Hamtramck from the remainder of their townships. This meant that Highland Park no longer had the possibility of itself expanding by annexation.