"I respect [Augustus Woodward] as a scientific man; and he may be useful where he cannot take the lead. He may suggest many brilliant things, which after being pruned, and qualified, may be useful. His Misfortune is that he cannot level his mind to the common—ordinary occurrences of life. The experience of past times is no lesson to him, and his ambition appears to be to surprise mankind by the singularity and novelty of his schemes."—William Hull to Thomas Jefferson, March 12, 1808

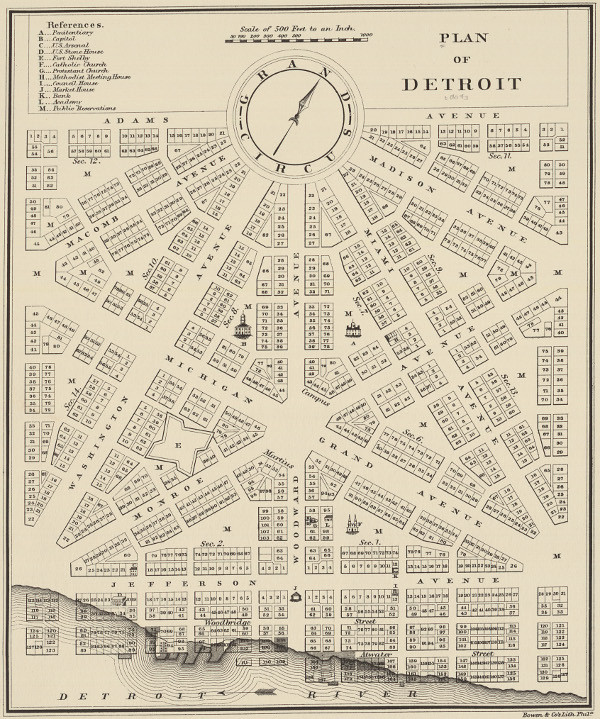

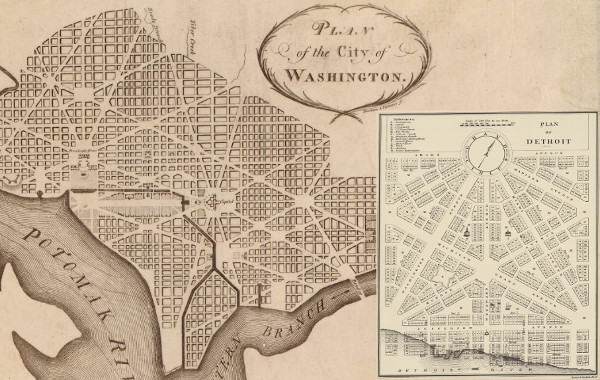

Philu E. Judd. "Plan of Detroit," (1824).

Image courtesy Clark Library, University of Michigan. (Source.)

This article is the first of a three-part series on Augustus Woodward's Plan of Detroit. Although there has been plenty written on this subject, I hope to offer a concise and detailed timeline of how exactly the plan came to be and why so little of it was ever implemented, and to bring to light a few lesser known facts about its history.

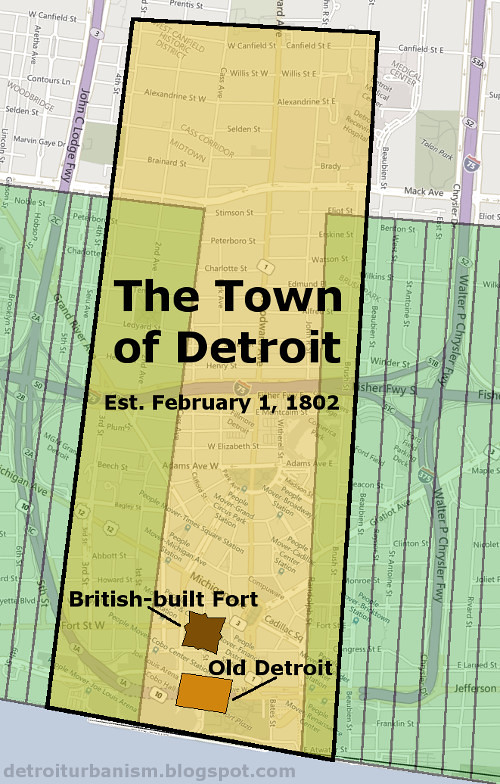

For the first century of its existence, Detroit was an unorganized community centered around a military outpost. On January 18, 1802, the Legislature of the Northwest Territory granted it township status, effective February 1 of that year. The new Town of Detroit was finally an incorporated municipality, able to elect its own board of trustees and write its own laws. Geographically, it included the cluster of about 300 buildings on the site of the old French fort, a newer British-built fort, the "Commons" (the public land surrounding the fort), and the two farms closest to the center of the settlement. The rear border of the town was two miles inland, parallel to the river.

On March 3, 1803, the portion of the Northwest Territory that included Detroit became part of Indiana Territory. Then on January 11, 1805, the U.S. Congress passed legislation creating the Territory of Michigan and making the Town of Detroit its capital. This law was to take effect June 30 of that year.

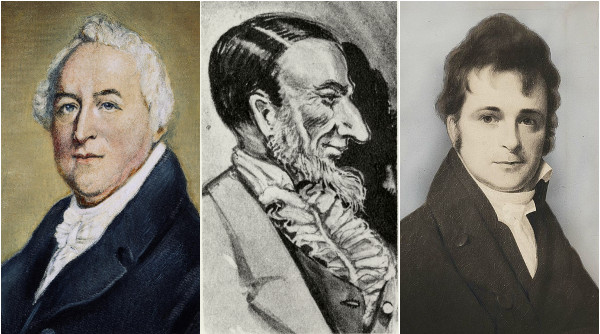

The new territorial government consisted of a governor, a secretary, and three judges. According to the law, the governor and judges also acted as the territory's only legislature. President Thomas Jefferson made the following appointments, all of which were confirmed by the Senate on March 1, 1805:

- Governor: General William Hull of Massachusetts

- Secretary: Stanley Griswold of Connecticut

- Judge: Augustus Brevoort Woodward of Washington, D.C.

- Judge: Frederick Bates of Detroit

- Judge: Samuel Harrington of Ohio, who declined the position

The Governor and Judges of the Michigan Territory. From left to right: Governor William Hull, Judge Augustus Woodward, Judge Frederick Bates. The portrait of Woodward is a caricature made after his death, based on descriptions.

You already know where this is going, so let's just get to it.

The Fire of 1805

Robert Thom, "The Detroit Fire: June 11, 1805," (ca. 1965).

Image courtesy Detroit Historical Society. (Source.)

On June 11, 1805, just days before Michigan officially became a territory, every building in Detroit except one burned to the ground. The town covered only two or three acres, but was very densely built. Incredibly, no lives were lost in the fire.

Judge Bates had already been living in Detroit at the time. Judge Woodward arrived June 29, followed by Governor Hull and Secretary Griswold on July 1. At a meeting of the newly assembled territorial government two days later, the following resolution was passed:

[T]hat a committee be appointed to take into consideration the present distressed and confused situation of Detroit, and to report to this body what measures may be incumbent on this Government in consequence thereof. ORDERED that the said Committee consist of one, and that Judge Woodward be the said Committee.At the meeting of the governor and judges on July 5, Woodward reported that "it will be proper to adopt a law constituting Detroit a city, and providing for the rebuilding and future regulation of the same in such manner as to prevent a similar calamity." Woodward's suggestions were approved, and he was ordered to "do and report conformably" to them.

He would devise a plan intended to prevent the rapid spread of fire, with large building lots and unusually broad avenues. But it would be no simple gridiron system, like Philadelphia or New York, but an entirely new design unlike any the world had ever seen.

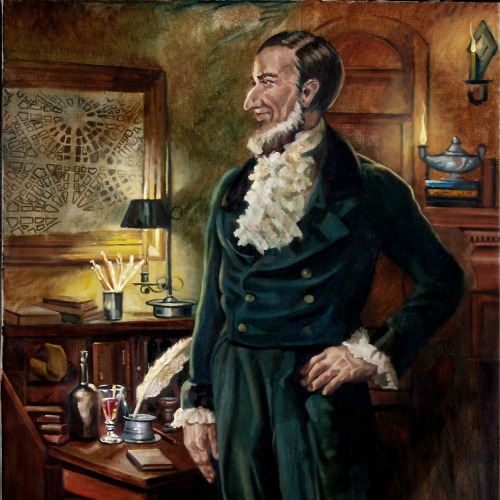

Augustus Brevoort Woodward

Woodward was not exactly a wizened old judge when he arrived at Detroit, being just thirty-one when he received his appointment. He was, however, a man of some education and experience. He enrolled at Columbia College of New York at fifteen and earned his Bachelor of Arts degree by nineteen. In 1795, he befriended Thomas Jefferson, a fellow lawyer with whom he shared a love of science, literature, and civic affairs. Two years later, Woodward moved to the District of Columbia, where he established the territory's first law practice. He was active in influencing public opinion on how D.C. was to be governed, writing a series of pamphlets under the pseudonym Epaminondas. When the City of Washington was granted a municipal government, he served on its first city council.

Portrait of Augustus B. Woodward by Robert Maniscalco.

Woodward was infamous for his eccentricity. His birth name was Elias, but like the Roman Emperor Octavius, renamed himself Augustus. In 1801 he published Considerations on the Substance of the Sun, which concluded that the sun was composed of "electron." [sic] "He was tall," according to one historian, "about six feet three or four, lean and stooped." Another wrote: "His personal habits were slovenly, and his room was conspicuous for disorder."

In Detroit, Woodward was a founding member of one of the first public school systems in the United States, which he named the "Catholepistemiad" and organized according to his book, A System of Universal Science. It was to have thirteen didaxiae (professorships) given titles in a mish-mosh of Greek and Latin that Woodward made up, including physiosophica (natural philosophy), iatrica (medicine), polemitactica (military science), and so on. This institution still exists, but it is now called the University of Michigan. Woodward was stubborn, argumentative, and erratic, but he was also a dreamer and an idealist. He was exactly the sort of person who would come up with something like the Plan of Detroit.

Possible Influences

It was in the City of Washington that Woodward met Pierre L'Enfant, the French-born architect who drew the first plan for that municipality. Much is made of the apparent similarities between Washington and Detroit, with an assumption that Woodward copied L'Enfant's design. Both plans make use of broad, diagonal avenues that terminate in public circles and grand squares, but there are fundamental differences between them. Washington is simply a gridiron pattern with diagonal avenues cutting through it, while Woodward's plan is a patterned, unified system. The diagonals in Woodward's plan are integral to it, rather than forced upon it. The uniformity of Woodward's plan yields a symmetry that L'Enfant's plan lacks.

Early plans for Washington, D.C. and Detroit.

Washington, D.C. was not the first planned city to utilize grand public circles and diagonal thoroughfares. After the London fire of 1666, Christopher Wren and John Evelyn both proposed new street designs that included these elements, but few of their ideas were implemented. Francis Nicholson had more success with his 1695 plan of Annapolis, which used public circles and diagonals on a much more modest scale.

Left: Wren's plan of London (1666); right: Nicholson's plan of Annapolis (1695).

While L'Enfant's plan was an improvement on its predecessors, Woodward's system was the first to take these promising elements of urban design and develop them to their full potential. These crude ideas were perfected at last.

The Survey

Although Woodward had a vision, he lacked the tools and training necessary to make it a reality. The governor and judges required the services of a land surveyor. "We immediately fixed on a plan," wrote Hull to Secretary of State James Madison on August 3, 1805, "and employed the best Surveyor we could find in the Country to lay out the Streets, Squares and lots."

That surveyor was Thomas Smith, a native of Wales and a former resident of Detroit. He remained a British subject after the U.S. took over Detroit, and moved to the Canadian side of the river. Although he was a foreigner, he was familiar with the land and no American surveyor was available. Woodward hired him to both perfect the plan on paper and stake it out on the ground. Smith would later write that the survey was executed "according to an idea suggested by Mr. Justice Woodward which required more than ordinary pains to be rendered practicable." Although Smith never took credit for the basis of the plan, he did state that he "had no little share in its construction, deduced from the ideas of Mr. Justice Woodward."

Before the groundwork could begin, Smith had to establish a meridian--i.e., to determine true north. Magnetic north was useless for such a project. Finding a meridian required astronomical observations. Detroiter John Gentle, who had a personal vendetta against Woodward after losing a court battle, mocked him in a sarcastic account of the survey published two years later in the Aurora General Advertiser of Philadelphia:

After a few days spent in preparing their apparatus, the judge began his operations on a height contiguous to the fort. There he placed his instruments, astronomical and astrological, on the summit of a huge stone, which stone shall ever remain a monument of his indefatigable perseverance.Woodward addressed this criticism in a letter to Madison:

For the space of thirty days and thirty nights he viewed the diurnal evolutions of the planets, visible and invisible, and calculated the course and rapidity of the blazing meteors. To his profound observations of the heavenly regions the world is indebted for the discovery of the streets, alleys, circles, angles, and squares of this magnificent city,—in theory equal in magnitude and splendor to any on the earth.

"It is true that I assisted [Smith] in taking a meridian line, and in adjusting his survey, both on paper, and on the ground. It is not true that thirty days and thirty nights were employed in taking observations. A meridian line, from which all the others were run, was taken from one solar observation, and one sidereal observation on the night of the same day, within fourteen or fifteen hours from the first."What was the nature of Smith and Woodward's observations? Finding true north is more complicated than simply pointing to Polaris, the North Star, because it does not always indicate true north. This star actually circles the North Celestial Pole once every 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds.

Polaris only indicates true north "P" when in positions "A" and "C." (Source.)

Smith could have measured Polaris' circular path in order to pinpoint true north. But as I learned from surveyor Joseph Fenicle, geodesists of that time had a shortcut. When Polaris reached culmination, it happened to be on a vertical plane with the North Celestial Pole and Alioth, a star in the handle of the Big Dipper. A surveyor could have suspended a plumb bob with a length of string or wire and then waited for the stars to rotate into position so that both Polaris and Alioth were exactly behind the line. At that instant, the line between the viewer and the string or wire was a true meridian. Smith, viewing the alignment with his theodolite (the "apparatus" mentioned by Gentle) would have known the exact deviation between true north and magnetic north.

If Smith and Woodward used this method, then I believe it happened in late August or early September for two reasons. First, Woodward mentioned a delay in finding a surveyor, and Hull reported in early August that that one had been hired. Smith likely would have perfected the plan on paper before staking out the Commons, so it's possible the groundwork did not begin until late August. Second, the Polaris-Alitoth-North Celestial Pole alignment occurred at a different time each day, and was not even visible throughout most of the year. Woodward stated that the astral sighting occurred "fourteen or fifteen hours" after solar noon. This alignment occurred between those hours from about August 19 to September 3 in 1805. On August 27, for example, the sighting would have been made fourteen hours and twenty-seven minutes after solar noon.

Detroit's northern sky, Aug. 27, 1805, 14:27 after solar noon.

The blue cross marks the North Celestial Pole.

Image generated by Your Horizon.

Due to axial precession, the vertical alignment of Polaris and Alioth no longer indicates an accurate meridian. In the 1890s, surveyors were able to use a similar method involving Mizar, another star in the handle of the Big Dipper, but this too is no longer useful.

Smith wrote to Judge Bates in October 1805 that he would accept a lot "on the Main Street" (Jefferson Avenue) or "half land & half money" as payment for his services. Smith said that he would be happy to continue working in Detroit "as it would be a pleasure to me to see the progress of the Town."

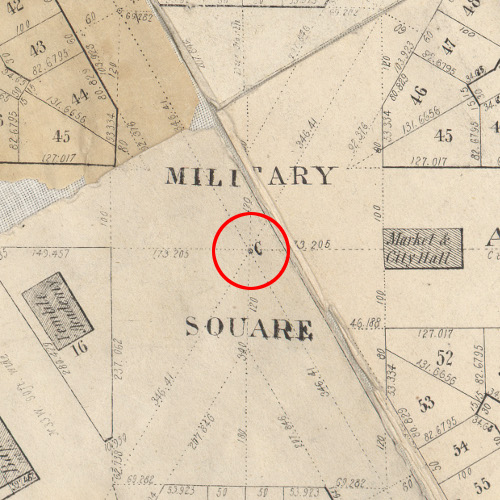

The Boulder

The "huge stone" mentioned in Gentle's account, where Smith and Woodward set up their base of operations, was a familiar landmark in old Detroit, located in what is now Campus Martius. In 1901, John C. Sabine recalled that James Witherell, who lived on the north side of Campus Martius, used to sit on this boulder. According to Sabine, it was located where the east side of Woodward Avenue met the north side of Monroe Avenue, and it measured three feet wide by three and a half feet long. Robert Leete, born in 1849, remembered the boulder from his childhood, estimating that it measured five feet across.

This mysterious granite stone became entangled with local legends. According to one account, Colonel Lewis Cass broke his sword over this boulder in August 1812 rather than surrender it to the British. It was also said that the stone was used as the foundation of the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. There is no historical evidence to support either myth.

At an unknown date, city planners wanted the boulder cleared from Campus Martius. Rather than attempt to haul it away, workers simply dug a hole next to it and rolled it in. When Mayor William C. Maybury learned about this buried boulder on the eve of Detroit's bicentennial, he declared, "I shall take immediate steps to locate the exact resting place of so interesting a relic... If it is discovered I promise you it will be raised and it will form yet another object of interest to associate with historical Detroit." ("Dig Up Famous Landmark." Detroit Free Press, May 20, 1901.) Despite the mayor's initial enthusiasm, it doesn't appear that these plans were carried out, or that the boulder's final resting place has even been discovered at all.

The Point of Origin

All surveys require a "point of beginning"--a precise reference point marked by a permanent physical monument or other landmark. For his survey, Smith established his point of beginning--commonly referred to as Detroit's Point of Origin--about 120 feet south of the boulder mentioned in Gentle's remarks. Originally this point was most likely marked by a large cedar stake. Although the stone itself was not the survey's point of beginning, it might have served as a useful landmark in helping to find the true Point of Origin on the grassy commons.

The idea of the town spreading as far as today's Campus Martius and Grand Circus Park was considered ridiculous by some residents. Several months after Gentle's attack in the Philadelphia Aurora, he wrote directly to President Jefferson, complaining that Hull and Woodward were wasting money by "digging wells and erecting pumps on the Commons, near half a mile behind the town of Detroit, where in our opinion no town will ever exist"!

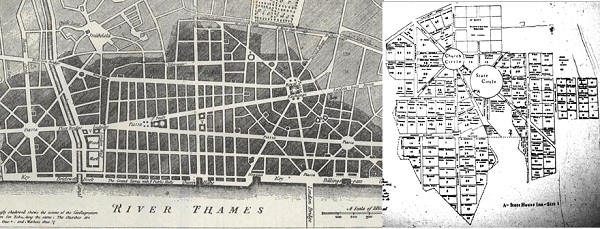

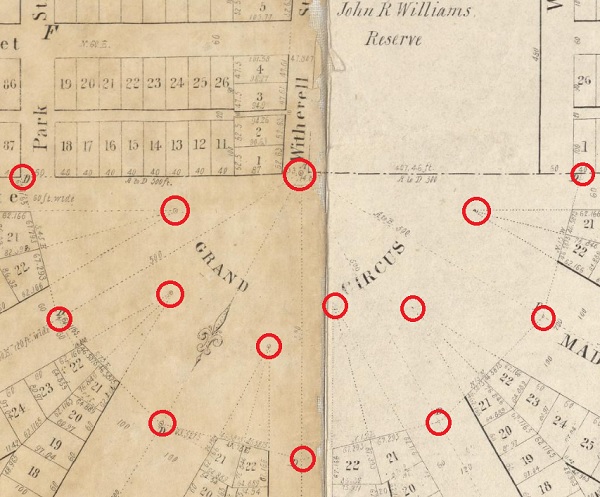

The Woodward Plan's Point of Origin, indicated on an 1835 map.

Image courtesy Clark Library, University of Michigan. (Source.)

The original Point of Origin was eventually replaced by a six-foot granite pillar placed vertically underground, likely as a result of this resolution of the governor and judges, dated June 8, 1819:

Resolved, that the surveyor of the Territory shall cause to be ascertained, by astronomical observations, a true meridian on the public space of ground, commonly called and known by the name of the Military Square in the City of Detroit, and shall cause the same to be denoted by substantial and permanent objects, fixed in the ground.

The granite monument was unearthed on May 19, 2003 during the construction of Campus Martius Park. News reports claimed that a bulldozer broke off the top eighteen inches of the pillar, but the contractors, Posen Construction, insist that no such accident occurred, and that it was found to have been broken into several pieces before it was uncovered.

Image courtesy James Foster, City of Detroit.

Image courtesy James Foster, City of Detroit.

Image courtesy James Foster, City of Detroit.

Image courtesy James Foster, City of Detroit.

Image courtesy James Foster, City of Detroit.

The location of the Point of Origin was carefully recorded using modern surveying equipment before removal. The restored marker was placed in a protective underground chamber at its original location in 2004.

Detroit's Point of Origin monument, returning to the center of the city.

Image courtesy Rosh Sillars. (Source.)

The completed park includes decorative granite pavers marking the location of Detroit's Point of Origin.

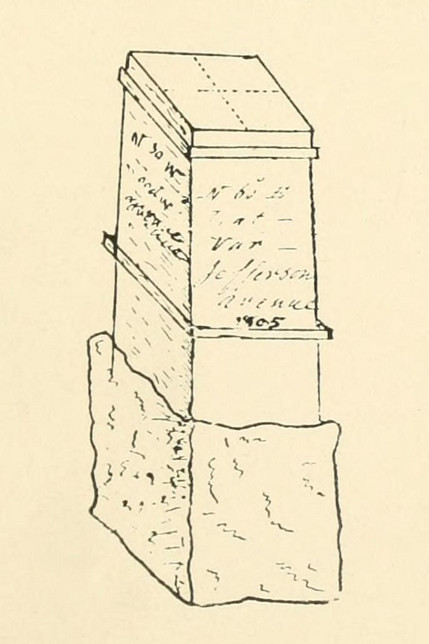

In a way, this is not the only point of origin in Woodward's plan. When the plan was legally codified in 1806, it was described as beginning at a stake planted in the middle of the intersection of Woodward and Jefferson Avenues. In 1821, Smith submitted a requisition to the governor and judges for a "stone of a foot square to be set in the line of Jefferson Avenue at the angle of the principal base, 5 or 6 feet in length." The requisition included a sketch of what the marker should look like:

Proposed marker to be placed at Jefferson and Woodward Avenues. (Source.)

It is not known if this marker now lies (or ever lied) beneath Jefferson Avenue.

When surveyor Hervey Parke traveled through Detroit in 1821, he described other markers in the vicinity of the Grand Circus:

About a half-mile from the present opera house stood a building appearing like a common barn on the farm of General J. R. Williams; from this point to the northwest no buildings were to be seen. In the vicinity of the barn before mentioned I observed four upright large stones of quarried granite, placed in form of a square, five or six rods (82.5 to 99 feet) from each other, said to be for the purpose of starting points for measurements on the angle for the streets.He probably saw some combination of monuments that marked the northern ends of several sections that converged near the intersections of Woodward and Adams Avenues.

Likely marker locations indicated on an 1835 map.

Image courtesy Clark Library, University of Michigan. (Source.)

The First Roads

Most of the new town fell within the Commons, which had been property of the U.S. government since 1796. Even as Smith labored over the survey in the late summer and early fall of 1805, the governor and judges were well aware they had no authority to divide, sell, or grant a square foot of federal land. Getting permission to do so was going to take several months that the people of Detroit simply didn't have. Although the territorial government couldn't issue deeds to the land, nothing prevented them from establishing roads.

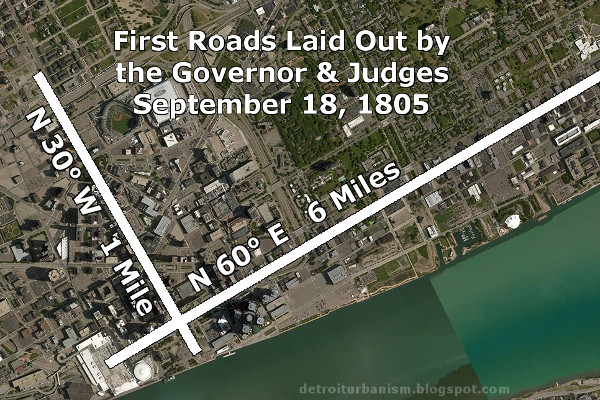

On September 18, 1805, the governor and judges passed An Act Concerning Highways and Roads. This law laid out two of the Woodward Plan's 120-foot-wide thoroughfares: six miles of today's Jefferson Avenue (from about Cobo Hall to Conner Street), and just over one mile of today's Woodward Avenue (from the river to what is now Sibley Street). Only small segments of these roads were actually cleared in 1805. Neither road was named at the time, but people soon began to refer to today's Jefferson Avenue as "Main Street."

Not only did this loophole help show the inhabitants where rebuilding should begin if the governor and judges' plan was approved--a few citizens didn't even wait for the law to be passed before constructing buildings. This legislation even uses two new houses as landmarks: that of Charles Curry, which stood at the southwest corner of the two new avenues; and the home of James Abbott, built on the north side of Main Street near the west end of the Commons.

Exchanged "Foot for Foot"

With the new town plan more or less settled, the governor and judges faced their next challenge: distributing property in a manner agreeable to everyone.

According to Hull's and Woodward's report to Congress, owners of lots in the old town exchanged their property for lots on the new plan "foot for foot," only paying for the additional square footage at auction. The prices they paid were used to determine the value of the land, which guided the sale of lots to renters who lost their homes in the fire. No money actually changed hands because the governor and judges openly acknowledged that they had no authority to sell land.

Hull and Woodward left for Washington that October, hoping to obtain congressional approval for all that they had done. They brought with them copies of Smith's rendering of the new plan. Not one copy of Smith's original plan survives today. Careless record keeping and alterations to the plan, both intentional and accidental, created a bureaucratic nightmare that would not be resolved for decades.

Smith continued his fieldwork after Hull and Woodward left. The people who built new houses along Main Street trusted that permission to do so would be granted after the fact. As winter set in, the people waited to learn the fate of their town.

Click here to continue to The Woodward Plan Part II: Dawn of the Radial City.

Looking forward to the continuation of this history. Will you be discussing the issue of transferring properties to allow placement of new roads where private property existed?

ReplyDeleteI probably won't be highlighting that in the context of the Woodward Plan, since it was never extended over private property. By the time the radial roads associated with the Woodward Plan were extended outward, they were considered military roads, and I will eventually have a post about those.

DeleteNow that I'm thinking about it... George Meldrum had to move buildings that were in the way of Jefferson Avenue in 1809, and he was reimbursed for the expense, but that land was not *technically* recognized as his private property by the U.S. government. There was a similar situation regarding the Catholic cemetery, which I'll be sure to mention in the next post.

I think it would be so neat if ever the Boulder could be discovered.

ReplyDeleteThank you for the great research. You're making the history of the city very interesting

ReplyDeleteExcellent work here Paul. As a surveyor using GPS, Robotics and Drones the work of the early surveyors truly fascinates me and gives me the utmost respect of their knowledge.

ReplyDeleteKeep up the good work - looking forward to round two.

Joseph D. Fenicle, PS

Fantastic post! I feel like I have to go out now and see the Point of Origin. Thank you for helping me get to know my city even better!

ReplyDeleteHey uh...I don't know if you realized it or not, but your description of the former location of "The Boulder" at the northeast corner of Woodward & Monroe puts it pretty much right under....the Hard Rock Cafe.

ReplyDelete;)

Great research. Here's a little research I've done on Grand Circus Park. http://ionosonderec.blogspot.com/2012/01/stonehenge-of-detroit.html

ReplyDeleteGreat job of research. I did done some research on this but did not find all you have about Smith. I did find he likely was assigned a theodolite by Surveyor General of Upper Canada, perhaps as early as 1788 and was examined to determine he could serve as a Deputy Surveyor. I also interpreted Gentiles comment about planets visible and invisible to indicate he may have made a determination of longitude since Jupiter's Galilean Moons were used to get Greenwich Time needed for such a determination. Marty Dunn and I have looked thru about have of Woodward's papers at Burton Hist Lib but have yet to find a record of such a determination. Would like to discuss info with you.

ReplyDeleteGreat research. Detroit has suffered to this day from overly-wide streets, which I believe Jefferson was even further widened as part of modernization. On Chicago's narrow street widths: "The first plat of Chicago determining the boundaries of streets and buildable lots dates to 1830, setting the streets to a width of 66 feet (the length of a surveyor's chain) and alleys to 16 feet of width bisecting evenly sized blocks. Named after its creator, the Thompson Plat of 1830 envisioned how the swampy lands beside a muddy prairie stream would eventually form a town and had set the basic standards of the street grid that would later spread throughout Chicago and its suburbs."

ReplyDeleteI've done research on this subject myself. The Woodward Plan can spin into a lot of geometry. Was wondering you did not show the famous plan drawn by Abyah Hull.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteJust visited Detroit for the first time & was fascinated by the origins stories. I also read about the pre-settlement Saginaw Trail and how Woodward Avenue follows that ancient alignment in the direction of Flint & Saginaw. Is it possible that Woodward used the Saginaw trail as his baseline? Did various other trails radiate out from the area of Campus Martius where "The Boulder" was before he even began his city plan - and if so, do you think those trails might even have been his inspiration for the radial street pattern? On a 1792 plan showing Fort Lernout there even seems to be a row of houses following the Woodward Avenue alignment...

ReplyDeleteThere's no way to know for sure if Woodward was inspired by the trails, but I don't think he was. The trails didn't really meet in the center of today's Detroit. The Saginaw Trail was the only one that came anywhere near today's Campus Martius. Others met the Detroit River outside of the original settlement. I looked up the 1792 map you mentioned, and that row of buildings is farther east than today's Woodward Avenue. I think those follow the western border of the Brush Farm, which follows a different angle than the avenue. In case you haven't seen this other post yet, I think you might find it interesting: http://detroiturbanism.blogspot.com/2016/01/retracing-detroits-native-american.html

DeleteThis is an old clip about the pattern and reasons for the city of Detroit Street patterns. https://archive.org/details/detroitspatternofgrowth

DeleteI have bookmarked your blog, the articles are way better than other similar blogs.. thanks for a great blog! Detroit

ReplyDeleteFor the first century of its existence, Detroit may have seemed unorganized to some observers, but certainly not as oxymoronic as claiming itself to be "centered around" a military outpost! Nothing can be "centered around" anything - as the center *is* the center and if something is 'around' then it is *not* at the center...

ReplyDeleteHow did Woodward define Detroit town planning

ReplyDeleteHaven't contacted your site in awhile. Woodward's overall plan was a hexagon but the basic unit to lay it out was a 30°-60°-90° triangle. Smith laid out each such triangle to lay off the lots on the 3 street with a public space in the middle, such as the Library near Washington Ave. All the streets run in true bearings of N30°E, N60E, N30W, N60W, etc. Smith could not have laid them our so exactly nor determined true north without a theodolite. But the plan was only laid in the public land around the fort. It was only laid out in the public land. The French who owned the private claims to either side of the public land (Woodward runs thru it) didn't appreciate nor understand the plan and didn't want narrow portions of it extended into their narrow parcels. Somewhat like Central Park in New Your City where it was intended to have many, only one was actually laid off. In Detroit only the central core was laid off but the major roads were extended for long distances but not on the exact bearing; rather they were blended into existing Indian paths.

ReplyDelete