On the outskirts of Detroit and in the suburbs, the land is covered by a gridiron network of concrete roads conveniently spaced one mile apart, sometimes referred to as the "mile road system". Some of these roads are named for their distance from downtown Detroit, beginning with Five Mile Road and continuing all the way up to Thirty-Seven Mile Road in northern Macomb County. This grid has such a dominance over the landscape that it is visible from outer space.

Metro Detroit's mile road system seen from space, Mar. 15, 2020.

(NASA)

This road network, crossing many municipal and county borders as if they weren't even there, was clearly the work of a deliberate, regional plan carried out long ago. This article looks into how and why this system was first conceived, who was responsible, and what historical events needed to occur first in order for it to happen. Also included is a history of Eight Mile Road's initial transformation from a narrow dirt road into the wide, divided highway it is today.

Before the System

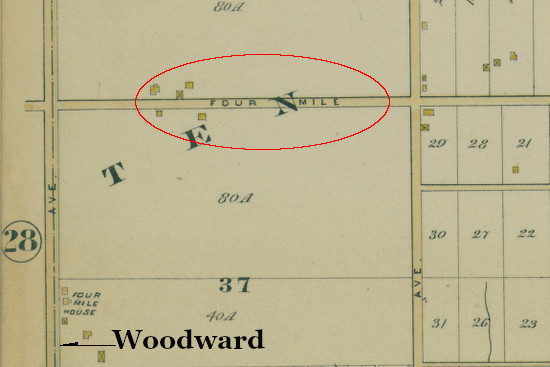

A convention of naming some east-west roads for their distance from downtown Detroit existed years before today's mile road grid was established. For example, Caniff Avenue once extended all the way to Woodward Avenue and was known as "the Four Mile Road." Today its path aligns with the alley between Trowbridge and Harmon streets in Detroit's Gateway Community neighorhood.

Four Mile Road as seen in an 1885 atlas of Detroit.

(University of Michigan)

Similarly, the name "Five Mile Road" once applied both to Davison Avenue east of Woodward and to Glendale Avenue west of Woodward. A few references to a "Three Mile Road" can be found in 1890s editions of the Detroit Free Press which may coincide with today's Grand Boulevard. However, none of these early mile roads had any connection to today's grid.

The Basis of the Grid

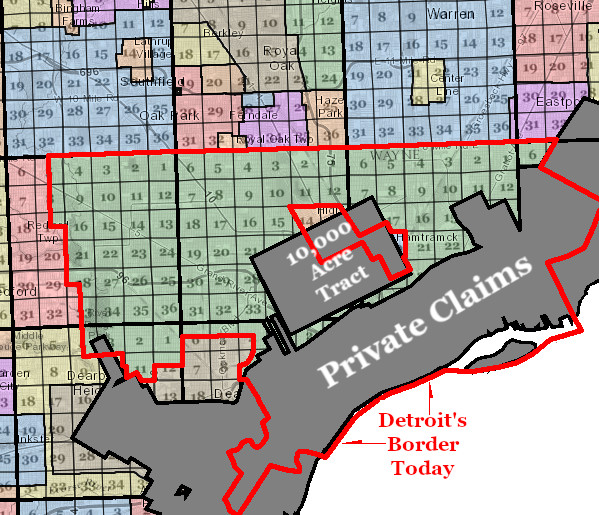

The locations of today's mile roads were drawn long before any human mind could have conceived of their existence. Beginning in 1815, the Federal government surveyed southeastern Michigan into square-mile sections according to the US Public Land Survey System. (This has been covered in detail in past articles—see: Part I: The Survey of Michigan, and Part II: The Survey of Metro Detroit.) The image below illustrates which parts of Detroit and the inner-ring suburbs have been surveyed according to the US Public Land Survey System.

The numbered squares represent Public Land Survey System sections. The City of Detroit is outlined in red. The Private Claims (also known as "ribbon farms") and the 10,000 Acre Tract have been discussed in previous articles.

The lines marking the boundaries of square-mile sections in the Public Land Survey System are called "section lines." Although they have always been the obvious place to reserve space for public roads, there was no organized regional effort to do so before the 1920s. At the time, cities and villages enjoyed paved streets and the railroad moved people and products between them. Out in the country, mud roads were nominally maintained by the townships, often with untrained farmers supplying the labor. These roads were only locally used, and were not even expected to be passable all year round.

Although the Three Mile, Four Mile, and Five Mile roads mentioned above were not section line roads, some of the section line roads north of them were sometimes given mile road names. Today's McNichols Road, for example, was sometimes called Six Mile Road at least as early as 1870.

Seven Mile Road in 1915 when this area was Greenfield Township.

(Hathi Trust)

The Good Roads Movement

Before a unified movement to pave all section line roads around Detroit could exist, several historical events would first need to unfold. One of the most important was the Good Roads Movement.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the most prominent advocates of improving America's roads were bicyclists, such as Horatio "Good Roads" Earle, once Chief Consul of the Michigan Division of the League of American Wheelmen (later renamed League of American Bicyclists). Earle organized the First International Good Roads Conference in Port Huron in July 1900 and was elected to the state senate that same year. As a state senator, Earle was appointed head of a committee to investigate the need for better roads in Michigan. The committee's recommendations resulted in the creation of the Michigan State Highway Department in 1905, and Earle was appointed its first commissioner. This new state department was empowered to subsidize highway construction outside of cities and villages.

(Wikipedia)

"I often hear now-a-days, the automobile instigated good roads; that the automobile is the parent of good roads. Well, the truth is, the bicycle if the father of the good roads movement in this country."

—Horatio Sawyer Earle (1855-1935)

The Wayne County Road Commission

Another important step towards the creation of the mile road system was the establishment of the Wayne County Road Commission. Since 1893, Michigan law had allowed counties to create road commissions to pave important rural highways and build bridges using county-wide taxes. However, none of the counties surrounding Detroit moved to adopt this system until after the State Highway Department was established in 1905. The Wayne County Board of Supervisors placed the question of whether or not to create a local road commission before voters at the September 1906 election, and the measure was overwhelmingly adopted. The first of the three members appointed to the commission was Edward N. Hines—who, like Earle, had served as Chief Counsul of the Michigan Division of the League of American Wheelmen. Hines would remain on the Wayne County Road Commission for 32 years.

(Hathi Trust)

Edward N. Hines (1870-1938)

The Wayne County Road Commission immediately got to work repaving important rural highways with macadam, composed of densely packed layers of crushed stone. Macadam roads served well for horse-drawn traffic and bicycles, but the passing of automobiles would lift dust out from between the pieces of crushed stone and blow it into the air, rapidly deteriorating the roadway. The necessity of a dustless substitute for Wayne County roads led to the commission's famous experimental first mile of concrete highway on Woodward Avenue between Six Mile and Seven Mile roads. The road commission was so pleased with the results that it adopted concrete pavement as the new standard for all county highways going forward. At this time, the State Highway Commission was helping offset road construction costs by offering all county road commissions $1,000 for every mile of highway rebuilt according to its standards.

These "before" and "after" photos appear in the Wayne County Road Commission's 1915 annual report. Seven Mile Road was still rural highway but an important link between Jefferson, Mt. Elliot, Van Dyke, Gratiot, Woodward, and Grand River avenues in the countryside north of Detroit.

(Hathi Trust)

Macomb County established its own board of road commissioners in 1912. Oakland County followed in 1913. The road commissions of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties would be necessary for the creation of a unified metropolitan highway grid.

The Detroit Rapid Transit Commission (RTC)

(Detroit Historical Society)

The mile road system finally came into being as a result of Detroit's efforts to establish a rapid transit system.

In the spring of 1922, the City of Detroit purchased all of the street car lines within its borders which had until then had been privately owned, and began operating them under the new Department of Street Railways. Detroit's population was breaching 1,000,000 at this time, and many felt that the city was ripe for modern rapid transit. Reports prepared by outside consultants had recommended such a system, including a subway for Woodward Avenue, in 1915 and 1918. However, Detroit Mayor James Couzens was not sold on the idea, saying that some rapid transit proponents just wanted to "satisfy their ego." ("Couzens calls tubes 'luxury.' Detroit Free Press, Jan. 7, 1922.)

Detroit Mayor James Couzens (1872-1936)

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

The mayor received pushback for his stance on rapid transit, especially from suburban real estate dealers. Detroit realtor Guy Ellis urged his colleagues in Birmingham to "support vigorously ... rapid transit" in order to increase the value of suburban property. ("Rapid transit is city need." Detroit Free Press, Feb. 5, 1922.) "Any city will stop growing when its transportation is inadequate," cautioned real estate operator C. J. Chapman. ("'Men in street' want 'L,' tubes." Detroit Free Press, Jan. 9, 1922.) Prominent realtor Harry A. Stormfeltz warned that "crowded apartment houses and congested tenements" would crop up unless a rapid transit system was built. ("Sees rapid transit near." Detroit Free Press, May 21, 1922.)

Despite his personal objections, Mayor Couzens succumbed to public pressure and asked City Council for $50,000 to fund an updated study of the city's rapid transit needs. The Detroit Free Press editorial board praised his decision, declaring that Detroit rapid transit would "provide convenient and swift communication with the surrounding country and open up a practically illimitable possibility of easy territorial expansion that will make for both health and wealth." ("On the right track." Detroit Free Press, Nov. 16, 1922.)

(freep.newspapers.com)

This article, "Prepared by the Publicity Department of the Detroit Real Estate Board," appeared in the Nov. 5, 1922 edition of the Detroit Free Press.

James Couzens would not remain Detroit's mayor for long. Following the resignation of Michigan Senator Truman Newberry in November 1922, Governor Alexander Groesbeck selected Couzens to replace Newberry as senator. Couzens, as his last official act as mayor, appointed four members to the new Detroit Rapid Transit Commission. ("Couzens quits M.O.; selects transit board." Detroit Free Press, Dec. 5, 1922.)

The chairman of the transit board which Couzens appointed was Colonel Sidney Dunn Waldon. The 49-year-old veteran of the First World War had formerly served as an executive at the Packard Motor Company and director of engineering for the Cadillac Motor Car Company. As a member of the city's Street Railway Commission and president of the Detroit Automobile Club and the Wider Woodward Avenue Association, Waldon was keenly aware of Detroit's transportation issues.

Colonel Sidney Dunn Waldon (1873-1945)

(Virtual Motor City)

The Superhighway Plan

(Archive.org)

After more than a year of study and preparation, the Detroit Rapid Transit Commission (RTC) unveiled a report, entitled Proposed Super-Highway Plan for Greater Detroit, on April 10, 1924. Intended to accommodate the region's growth for decades to come, the report outlined a plan for replacing the region's disjointed network of poorly maintained roads with an orderly grid of paved, modern highways.

As mentioned earlier, the foundation of this new road network was to be the US Public Land Survey System. Below is an image showing a typical township surveyed according to this system, measuring six miles on a side.

(Cadastral.com)

According to the RTC's general plan, highways were to be laid out on every section line within 15 miles of Campus Martius in downtown Detroit. Every third section line was to become a superhighway measuring 204 feet wide, while all other section lines were to be highways spanning 120 feet wide. The original plan also called for intermediate roads with a width of 86 feet—"half-mile roads". These were not hard-and-fast rules, but rather general guidelines for the region's growing transportation system.

Below is a detail from a 1925 map of the RTC's plan, showing how the Redford Township area was to be effected. Dashed lines are supposed to represent where no paved roads had yet existed.

(University of Michigan Library Digital Collections)

The extra-wide superhighways of the RTC's plan were not limited to the mile road grid. The report also called for widening several existing "diagonal" arterial roads (e.g. Woodward Avenue) in addition to creating several new ones (e.g. Northwestern Highway). The image below shows the locations of proposed 204-foot superhighways, as they appeared on a map published in 1925. Note that it was originally Seven Mile Road—not Eight Mile Road—which had been selected to become a superhighway. The red circle marks 15 miles from Campus Martius.

The commissioners were aware that they were facing historically unparalleled transportation challenges. Twenty-story office buildings and massive assembly plants employing thousands were concentrating workers like never before. And the mass of automobiles crowding every city street was growing every year. Unprecedented problems would require unprecedented solutions. The RTC's report stated:

Detroit is the automobile city of the world, and the growth of the city has been tremendously advanced by its position as the center of the automobile industry. [...] It is therefore most fitting, instead of waiting for some other city to set up the precedent, that Detroit, in co-operation with the counties and municipalities surrounding it, should take the lead in making adequate provision for the motor traffic needs of today, and the tremendous increase in motor traffic that will surely come in the future. [...] But in addition to providing for the increase in motor traffic that is inevitable, Detroit is also confronted with the necessity of providing rapid transit for immediate needs, and planning rapid transit for future requirements. So that there is a double reason for wide streets both inside and outside the city. (p. 13)

In other words, the reason for such wide public thoroughfares is because they were intended to serve both individual automotive transport as well as various forms of mass transit. Advertisements for suburban real estate immediately began including sketches of their subdivisions adjacent to mass transit rail lines running along superhighways which at that point existed in name only.

This advertisement for the Blackstone No. 2 subdivision, which ran just one month after the RTC's report, includes a sketch of the adjacent Seven Mile Road Superhighway, illustrating the rail lines which the thoroughfare was expected to carry. From the May 22, 1924 edition of the Detroit Free Press.

(newspapers.com)

Detail from the above Blackstone No. 2 advertisement from the Detroit Free Press, printed May 22, 1924. Note that Church Road is an old name for Hubbell Avenue.

(newspapers.com)

Detail from an advertisement for the Grandmont No. 1 subdivision by the Stormfeltz-Loveley Company from the August 17, 1924 edition of the Detroit Free Press. Note that Mill Road is an old name for Southfield Road.

(newspapers.com)

Although there were yet hurdles to overcome before the RTC's plan could be made legal or financially feasible, officials eagerly began work on transforming Woodward Avenue into the first superhighway. The State Highway Commission graded the west half of Woodward Avenue between Eight Mile and Ten Mile roads beginning in July 1924 and began pouring concrete the following month. By November, the initial 2.2-mile long, 40-foot wide concrete strip was open to traffic in both directions with much fanfare. ("Royal Oak merchants to fete new highway." Detroit Free Press, Nov. 14, 1924.)

The Public Right-of-Way

Dirt roads in surrounding townships had another disadvantage aside from being inconsistently built and maintained: the standard public right-of-way was just 66 feet. As Detroit expanded into rural territory, these roads would inevitably require widening by condemnation—an extremely lengthy and expensive process. According to the RTC, the top priority in moving forward with its plan was obtaining the corridors of land wide enough to construct the highways and superhighways. The Commission's report states:

The important thing is to acquire the right of way as quickly as possible. All right of way acquired now before the territory traversed becomes built-up will save condemnation of improvements and property later. The land needed will never be cheaper than it is today. For this reason it is most desirable that a plan for financing the purchase of the right of way be devised without delay. (p. 21)

The term "right-of-way" refers to the entire width of a transportation corridor. It includes not just the paved roadway, but also all sidewalks, landscaping, bike lanes, streetcar tracks, and everything else that falls on public property.

On this section of Six Mile Road in Redford Township, the central pavement is 50 feet wide, but the full public right-of-way actually spans 120 feet.

(Wayne County Parcel Viewer)

The width of 120 feet was determined to be the standard for all mile roads and other highways that weren't superhighways. At its maximum capacity in a high-density area, 120 feet could accommodate (as illustrated below): four 8-foot lanes for motorized traffic in each direction, two 15-foot sidewalks, and two 10-foot dedicated streetcar lanes with accompanying 3-foot safety platforms. Below ground, 120 feet provides adequate space for subways, including both express and local lines, with three loading platforms, and enough room for sewers between the foundations of surrounding buildings.

Efficient use of a 120-foot public right-of-way, as illustrated in a 1929 RTC report.

(Hathi Trust)

The 204-foot superhighway was designed to carry the same amount of traffic as illustrated above (except street cars) all at surface level. These types of thoroughfares were planned almost exclusively for the suburbs, where land was cheaper to obtain. The superhighway right-of-way was designed to include: two 15-foot sidewalks; two 10-foot "local" motor traffic lanes in each direction; two 10-foot "express" motor lanes where non-stop driving would be made possible by bridges built every half mile (!); two 5-foot safety zones separating local and express motor traffic; two 15-foot lanes for local commuter rail; two 15-foot lanes for express commuter rail; and two 12-foot landscaping strips separating motor from rail traffic.

(Archive.org)

Illustration of a 204-foot-wide superhighway from the Detroit RTC's 1924 report.

(Detroit Historical Society)

Although many state and local laws would have to change before the government was allowed to begin obtaining right-of-way for the superhighway system, some suburban real estate dealers were perfectly happy to give the land away for free, increasing their property's value. One prominent example was Detroit realtor Burnette F. Stephenson, who had been involved in establishing a streetcar line connecting Highland Park to Royal Oak since 1915. In 1919, Stephenson and other developers convinced the Detroit United Railway to begin constructing the "Stephenson Line" on private right-of-way paralleling Oakland Avenue through their properties in what is now Hazel Park. Following the unveiling of the RTC's superhighway plan, Stephenson's company publicly dedicated the required right-of-way north of Eight Mile Road. An article in the Detroit Free Press, prepared by Stephenson's office, reported in September 1924:

The development of this section has been so rapid that this year we recognized the fact that Oakland avenue as laid out by us in 1916 should be changed and converted into a super-highway. With the hearty co-operation of the rapid transit and city plan commissions and Oakland county officials, Oakland avenue, from the city limits north to the intersection of Fourth street in Royal Oak, has been designated as the Stephenson super-highway, and this office has spent thousands of dollars in the purchasing of lots and additional lands to provide for the widening of this artery to 204 feet. We started a campaign of development and now have practically completed the first mile of the Stephenson super-highway, lying between the 9½ and 10½-mile roads, which super-highway was officially dedicated Saturday.

("Oakland and John R. development traced." Detroit Free Press, Sep. 28, 1924.)

Realtor Burnette F. Stephenson ran this full-page advertisement for properties along the Stephenson Superhighway in the September 28, 1924 edition of the Detroit Free Press on the day after donating one mile of right-of-way.

(newspapers.com)

Making it Legal

Nobody had ever proposed such a vast grid of concrete roadways, uniting cities, villages and townships spread across multiple counties. Facilitating and legalizing the superhighway plan was going to require new legislation at the state level. Meanwhile, Detroit began taking steps to get the project started within its own borders. At the city election of September 9, 1924, voters approved a charter amendment which made the RTC a permanent city entity and spelled out a plan to finance a mass transit system. ("Voters clear way for completion of rapid transit plan." Detroit Free Press, Sep. 14, 1924.) The RTC submitted its superhighway plan to the Detroit City Council in March 1925, which was adopted as the city's own master plan (within its own borders) on April 14, 1925.

The following month, the state legislature finally passed several laws enabling the realization of the superhighway plan:

- Public Act 224 of 1925 (§y) permitted cities to construct, finance and own rapid transit systems. Approved May 6, 1925.

- Public Act 352 of 1925 simplified and expedited the process of condemning land for highway purposes. Approved May 27, 1925.

- Public Act 360 of 1925 required all new subdivision plats to conform to any street or highway plan adopted at the municipal or county level. Approved May 27, 1925.

- Public Act 381 of 1925 allowed any two boards of county supervisors to enter into contracts in order to plan and construct superhighways, which the law defined as being any highway with a width from 120 feet to 204 feet or more. This legislation also permitted the creation of county superhighway commissions, who were empowered to receive or purchase land for superhighway right-of-way. Counties were empowered to impose a half-mill tax for the purposes of obtaining this land. Approved May 27, 1925.

With the appropriate legislation then enacted, Detroit next asked voters to approve four ballot measures at the city election held November 3, 1925. All four proposals passed by wide margins:

- A city charter amendment granting the city the authority to designate rapid transit routes and to construct mass transit lines—either subway, surface, or elevated—as permitted by the new state legislation. [Yes 73.4%, No 26.6%]

- A city charter amendment enabling the city to create special assessment districts, and changing the way the city was allowed to take land for road widenings, so that small, unusable lots are not left over. [Yes 75.5%, No 24.5%]

- A city charter amendment giving the city the power to redraw lot lines when a street is widened and to establish building setback lines. [Yes 75.8%, No 24.2%]

- A proposal authorizing a one-mill city property tax to establish a sinking fund in order to pay for street widenings. [Yes 69.5%, No 30.5%]

One United Metropolis

The first inter-county superhighway commission that was formed under the authority of Act 381 was the Wayne-Macomb commission, established on December 4, 1925. The Wayne-Oakland Superhighway Commission was created one week later, on December 11. As a rule, inter-county superhighway commissions consisted of seven members: the three members of each county's road commission, plus the State Highway Commissioner.

This article from the December 5, 1925 edition of the Detroit Free Press about the formation of the Wayne-Macomb Superhighway Commission reports "there will be at one mile interval [sic] a road known as a section line road, 120 feet wide."

(newspapers.com)

In early 1926, the suburbs that had incorporated as cities by this time began to adopt city charter amendments ensuring their ability to cooperate with the superhighway plan. The City of Highland Park approved such an amendment on March 1, 1926, followed by the cities of Fordson (which later became part of Dearborn) and Hamtramck on April 5, 1926. It seemed that traffic congestion had finally brought together disparate communities which had previously been at odds with one another on other city planning issues. In an August 1926 report, the RTC explained the logic of regional cooperation in the name of the superhighway plan:

There is a great daily interchange of population between Detroit and her neighbors. So many of their industrial workers are Detroit residents, and vice versa, that the transportation problem does not belong particularly to Detroit any more than it does to Fordson, Highland Park, Hamtramck, or any other municipality. It belongs jointly to the whole Metropolitan Area. Therefore, the service of the rapid transit facility must be considered as if the whole transportation district were a single community and the costs of construction equitably distributed as if no political subdivision existed.

(Rapid Transit System for the City of Detroit, p. 12)

The unifying effect of the superhighway plan was altering the map of Detroit in more ways than one. Prior to this time, Detroit maps were normally rotated about thirty degrees counterclockwise, so that the Detroit River ran horizontally at the bottom with Woodward Avenue running vertically up the center. Following the unveiling of the mile road plan, with its sprawling checkerboard of roads neatly aligned with the points of the compass, publishers finally began to orient maps of Detroit with north at the top as it is done today. ("Map of city finally turned right side up." Detroit Free Press, Feb. 15, 1925.)

This 1919 map by William Sauer is an example of how Detroit maps were oriented before the advent of the mile road system.

(UM Clark Library Maps)

Below is the RTC's initial superhighway plan, published in 1925, oriented with north at the top.

"Super highway and major thoroughfare plan for Detroit and vicinity : as prepared by City Plan Commission and Rapid Transit Commission in collaboration with the Road Commissions of Oakland, Wayne and Macomb Counties and the authorities of included municipalities." (1925)

(University of Michigan Library Digital Collections)

In a May 1926 Detroit Free Press article about the superhighway plan, RTC engineer John P. Hallihan wrote that, in the old days of city planning,

...the balance of power was overwhelmingly on the side of individualism. The community as a cohesive unit in thought and action was of little consequence.

Now the conditions are reversed. The community has come to the realization that its negligence in the past in exercising control over its street system has put it in a position where it must think broadly and act promptly to escape being choked by its own needs in trafficways.

In Detroit the community feeling has been cultivated and expanded by the Rapid Transit commission and the City Plan commission by means of neighborhood councils so that the planning for the future is now being done from a regional viewpoint covering the three counties of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb.

("Dream of east-west super-road fulfilled." Detroit Free Press, May 23, 1926.)

Eight Mile Road

Although Eight Mile Road occupied an important position—lying on the Michigan Baseline and forming the northern boundary of Wayne County and the City of Detroit—it was just another derelict country road in the 1920s. "For the very reason that it is on the line between counties," one newspaper observed, "an obstacle has existed in the way of opening and improving it because, until the 1925 legislature, there was no adequate machinery for joint highway work by counties. Instead of being a model highway, it has been neglected and in some stretches not opened at all." ("Base Line Road to be superhighway." The Farmington Enterprise, Feb. 12, 1926.)

Looking east along Eight Mile Road across Coolidge Highway, April 19, 1927.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 23.)

The destiny of Eight Mile Road would change forever at a joint meeting of the Wayne-Macomb and Wayne-Oakland superhighway commissions on February 2, 1926. Commissioner Herman A. Miller of Macomb County introduced a motion that Eight Mile Road should be designated a 204-foot superhighway from Grand River Avenue on the west to Vernier Road on the east. After some debate, the motion carried unanimously. Although it was initially reported that Eight Mile Road would "not be part of the super-highway system master plan" and "would not in anyway change the status of Seven Mile road" ("Will improve two highways." Detroit Free Press, Feb. 3, 1926.), these alterations ended up becoming permanent after all. The only part of Seven Mile Road to become a superhighway was the section now known as Moross Road.

Above: Detail from the road map in the Wayne County Road Commissioners' annual report for 1925, showing improved county roads (solid red lines) ending at Eight Mile Road, which remained unpaved at the time. (Archive.org)

Below: Detail from the map in the Board's 1926 annual report with Eight Mile Road highlighted with a broken green line, indicating that it was being taken over as a county road. (Archive.org)

The portion of Eight Mile Road lying between Farmington Road and Grand River Avenue would be an ordinary mile road, with a 120-foot right-of-way and an initial 20-foot concrete roadbed. The 204-foot superhighway portion, which ran 21 miles from Grand River Avenue to Mack Avenue and included part of Vernier Road, was divided into four sections. Each section had a different plan for expanding the road's original 66-foot right-of-way:

- Section A—Grand River Avenue to Greenfield Road, 69 feet taken from each side of the road.

- Section B—Greenfield Road to John R Road, 138 feet taken from north side of the road.

- Section C—John R Road to Van Dyke Avenue, 138 feet taken from south side of road.

- Section D—Van Dyke Avenue to Mack Avenue: 69 feet taken from each side of the road up to Gratiot; 138 feet taken from north side of road between Gratiot and Kelly.

The initial plan for Section D called for the superhighway to be centered over the old road. ("Wayne's new bureau to expedite projects." Detroit Free Press, Nov. 14, 1926.) The reason for shifting the road north between Gratiot and Kelly appears to be Detroit's Regent Park neighborhood, southeast of Gratiot and Eight Mile, which had been subdivided by 1926. The north side of the road contained mostly unsubdivided property lying in Warren Township, which was cheaper to condemn. One of the few subdivisions on the north side of the road was the "Michael & John Sprenger Subdivision." The image below shows the original lot lines of part of this subdivision, including all of the commercial lots which were condemned to become part of the public right-of-way.

Part of the "Michael & John Sprenger Subdivision," City of Eastpointe.

(Macomb County Parcel Explorer)

Although the government had been equipped to buy or condemn property for the superhighway project, the advantages brought by these new highways encouraged owners to donate the necessary land. In a March 1926 address before an audience of real estate salesmen, City Plan Commissioner T. Glenn Phillips promoted the voluntary donation of right-of-way in order to speed up suburban development. ("Urges giving highway sites." Detroit Free Press, Mar. 28, 1926.) His speech also highlighted the unifying effect of the superhighway project:

Artificial boundary lines have been swept aside in this great metropolitan movement, and officials in counties and towns adjacent to Detroit are now able to concentrate their street opening and widening expenditures along the routes that are unmistakably of benefit to the entire metropolitan area. Thus we find Oakland, Macomb and Wayne counties uniting this year in the improvement and pavement of the Eight-Mile super-highway, which lies partly in the limits of all three....

By early June 1927, the Eight Mile Superhighway Improvement Association reported that 21,990 feet of property fronting Eight Mile Road had been dedicated for the project between Grand River Avenue and Greenfield Road, with about 11,000 left to go. Real estate firms were the largest donors. ("21,990 ft. donated for new highway." Detroit Free Press, Jun. 5, 1927.) Despite these efforts, not everyone was willing to donate. Condemnation proceedings were required for many parcels after all. As we will see later, condemnation rewards to landowners quickly evaporated in the face of steep state highway tax assessments imposed on their property.

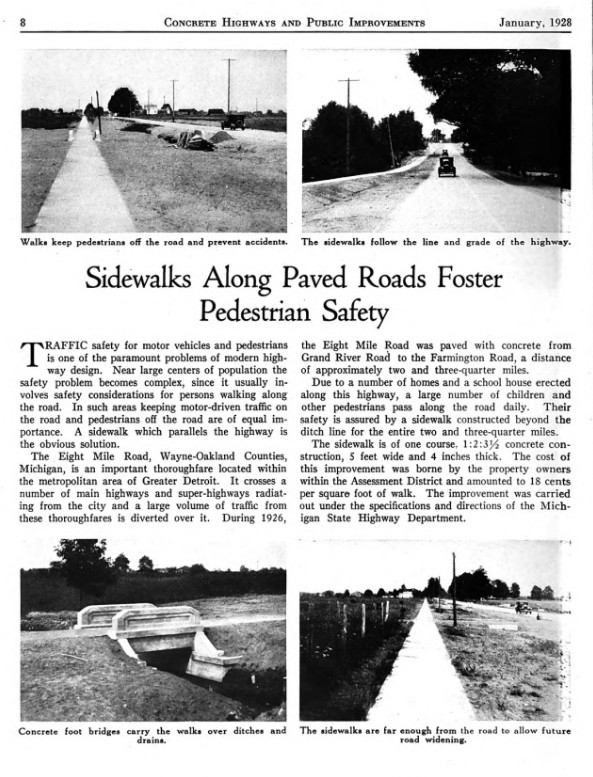

The first part of Eight Mile Road to be constructed under the new plan was along the 120-foot right-of-way running between Farmington Road and Grand River Avenue. An initial a 20-foot concrete pavement was constructed, later to be expanded to 40 feet. ("Wayne shatters all marks in road construction." Detroit Free Press, Oct. 2, 1927.) This section was open to automobile traffic by June 1927. Commissioner Hines remarked: "Of special interest in construction of the Eight Mile road improvement is the laying of the first county sidewalks. These sidewalks have been built adjoining the new road for the safety and convenience of school children in the vicinity who might for lack of walks be forced to the pavement." ("3 miles of Base Line Road open to traffic." Detroit Free Press, Jun. 12, 1927.)

Page 8 from the January 1928 issue of Concrete Highways and Public Improvements.

(Hathi Trust)

The first superhighway portion of Eight Mile Road to be built was the southern half of Section B, the five-mile span between Greenfield and John R roads. Construction began in May 1927. ("Eight-Mile Road to serve Detroit east side." Michigan Roads and Pavements, Jun. 9, 1927.) A single 20-foot pavement was laid down, temporarily serving traffic going in both directions until the so-called "north slab" was completed. Each 20-foot pavement would later be widened to 40 feet. This section is depicted in the photograph below.

Facing west along the "south slab" of Eight Mile Road, one half mile west of Woodward Avenue, on August 27, 1928.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 24)

Detail from the photo above. Lafond Veterinary Hospital, on the left, is still in operation here (under new ownership) at 3191 West Eight Mile Road. The house in the background is 20539 Picadilly Road in Detroit's Green Acres neighborhood.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 24)

The next section of Eight Mile Road to be built was the south slab of Section C, between John R and Van Dyke, under construction by July 1928. ("50 miles of new roads to be built in 1928." Detroit Free Press, Jul. 22, 1928.) The north slab of this section was open to traffic by the autumn of the same year. ("Base Line road work is rushed by Wayne commission." Michigan Roads and Construction, Sep. 20, 1928.)

Looking west along Eight Mile Road across Oakland Avenue (now I-75) in Section C, November 1, 1928.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 24)

The massive scale of Eight Mile Road dwarves a human figure standing in the median, east of John R Road in Section C. This view was taken facing east on November 1, 1928.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 24)

Detail from the photograph above. The homes in the background belong to Detroit's Nolan neighborhood. The house on the far right is 20520 Keating Street.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 24)

Detail from plat of "Gilmore & Chavenelle's Subdivision No. 2," platted in 1919, superimposed over a Google Earth satellite image from 2023. 20520 Keating Street, from the previous image, stands on lot number 554.

Facing west on Eight Mile Road west of Dequindre Road, Section C, August 29, 1929.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 25)

Roadbuilders next shifted their attention toward Section D, the easternmost portion, which runs from Van Dyke to Mack Avenue. A 20-foot concrete pavement was poured in the south half of the roadway in 1929, which was ready for traffic around late September of that year. ("Airport drive open to public." Detroit Free Press, Sep. 22, 1929.) At this point, the south half of Eight Mile Road ran continuously from Greenfield Road to Mack Avenue.

The "Base Line Subdivision No. 2," platted in 1923, lies on Section D of Eight Mile Road. A tier of commercial lots has been incorporated into the 204-foot right-of-way. The Michigan Baseline is highlighted in yellow.

The north half of section B (Greenfield to John R) was constructed in two segments. Work began on the part between Livernois and John R in June 1929 and was open by September 1930. ("Progress made on Base Line." Detroit Free Press, Sep. 28, 1930.) The remainder of the north pavement, from Greenfield to Livernois, was completed in late July 1931. The north slab of Section D (Van Dyke to Mack) was also finished at this time. ("Span opens Labor Day." Detroit Free Press, Jul. 19, 1931.)

Facing east down Eight Mile Road from Kelly Road, Section D, August 26, 1931.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 27)

Detail from the previous photograph. The bend in the road is where the superhighway turns away from the old Base Line Road and follows Vernier Road down to Mack Avenue. The Stricker Farmhouse, on the right, would later become part of the parking lot for Eastland Mall.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 27)

After the passage of the state superhighway laws, the three local counties adopted ordinances requiring subdivision plats to conform to the master plan. For example, the "Ternes Superhighway Subdivision" was platted in 1926, southwest of Eight Mile and Kelly roads. In order to prevent the need for condemning parcels of land, the subdivision plat itself incorporated the necessary rights-of-way.

Plat of the "Ternes Superhighway Subdivision" (1926).

Detail from the plat of the "Ternes Superhighway Subdivision," showing allowances for the Eight Mile Road and Kelly Road superhighways, preventing the need for future road widenings.

Stamps of approval from Detroit's Common Council, City Plan Commission, and City Engineer for the "Ternes Superhighway Subdivision" plat.

The "dedication" from the "Ternes Superhighway Subdivision," by which the landowners, Anthony and Catherine Ternes, deeded all rights-of-way to the public. They most likely received compensation for this land—as well as a huge tax assessment to pay for the road.

The final segment of Eight Mile Road to be completed under the superhighway plan was Section A (Grand River to Greenfield), where work was delayed by several condemnation cases. ("County road plans pushed." Detroit Free Press, Jun. 30, 1929.) By late 1931, the entire Eight Mile Road project was finished all the way from Farmington Road to Mack Avenue.

Five years prior, just as work was beginning on the concrete superhighway lying between Detroit and its northern suburbs, a local realtor notably predicted: "The time is not far distant when all of the territory south of the Eight-Mile road will be known as Old Detroit, and all on the north side will be called 'The New Detroit.'" ("'New Detroit' to rise soon on east side." Detroit Free Press, Apr. 4, 1926.)

Detroit Free Press, April 4, 1926.

(Newspapers.com)

Roads "to Nowhere"

Throughout the seemingly endless economic growth of Roaring Twenties, enthusiasm for the superhighway plan ran high. But by the time Eight Mile Road was fully paved, two years following the stock market crash of 1929, public opinion had definitely cooled. After Wayne County Road Commissioner Edward Hines announced the completion of Eight Mile Road, the following appeared in a column in the Detroit Free Press:

No doubt there is somebody in town who would like to drive 23 miles from one end of Eight Mile Road to the other. It's all right. It can be done. Road Commissioner Hines reports to this department that there is now an unbroken stretch of concrete from Mack to Grand River Ave. If you follow the route you can see some high faluting and expensive grade separations. If you get tired of the Eight Mile Road, and you probably will, you can turn off on any number other perfectly good superhighways. Mr. Hines will furnish a list of them on application.

("With the builders and realtors." Detroit Free Press, Nov. 1, 1931.)

[Incidentally, a song published in 1926, "Up and Down the Eight Mile Road" (YouTube, PDF), already hinted at a few novel ideas for staving off boredom while traversing this very thoroughfare.]

The Great Depression decimated land values, which in turn required an increase in the tax rate. In some instances, landowners were left with property worth only a fraction of their assessed valuation and unable to pay their tax bill. The Detroit Free Press cited the story of Walter Blaszewski, a farmer who owned 42 acres on Eight Mile east of Lahser, whose farm was assessed at $1,700 an acre but was willing to sell it for $500 an acre to anyone willing to pay the taxes owed.

Blaszewski revealed that while his city taxes this year would amount to $1,420, that the state has a special assessment against his property of $19,176, due to the highway tax. Blaszewski's case was considered typical of land owners along the Eight Mile road. He stated that he was just a poor man, trying to support a wife and nine children, and working the farm and doing day labor on the side. The state took some of his land for a new highway and paid him $15,000 for it. This was all taken back in taxes, he added, and the $20,000 tax still stands."

("Tax protests keep coming in." Detroit Free Press, Apr. 28, 1931.)

In addition to complaints like Blaszewski's, the discovery of major discrepancies in tax assessments along Eight Mile Road led to an investigation by the Detroit Board of Tax Review. ("City orders tax suit in 8-Mile widening." Detroit Free Press, May 6, 1931.)

Before: Looking east down old Base Line Rd. at Grand River Ave., April 19, 1927.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 23)

After: Facing east on the new Eight Mile Road Superhighway at Grand River Ave., August 26, 1931.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 27)

Detail from the previous photo. This is the point where the road expands from a 120-foot right-of-way into its full 204-foot "superhighway" width.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 27)

In April 1932, former judge Arthur J. Lacy, then considering a run for governor, attacked the state government for failing to fund the distribution of medicine for children during a 1931 polio outbreak, while at the same finding "millions with which to widen Eight Mile Road, a highway that runs from nowhere to nowhere and passes through no place and which nobody needed... lined on both sides with homes of persons unable to pay their taxes." Michigan spent nearly $40 million, he said, "to make ribbons of cement on which folks could ride over the hills to the poorhouse." While admitting that Lacy's remarks were "a little bitter," a Detroit Free Press editorial concurred with the judge, adding:

It must be apparent to anybody who motors about Michigan and particularly about the southeastern part of Michigan, that many millions of dollars have been thrown away in the construction of improved roads which were not needed and are almost unused. A person who wants to enjoy a nice quiet drive where he will meet little or no traffic, cannot do better than adventure abroad on them. He will find solitude, and hear only the sounds made by his motor and the frogs in the wayside ponds. The roads are beautifully laid but they are a fearfully expensive luxury for a tax-ridden State whose officials cannot find even $10,000 with which to get medicine that will save little children from the consequences of a fearful disease.

("Millions for roads; nothing for children." Editorial. Detroit Free Press, Apr. 30, 1932.)

Property owners in Macomb County sued the State Highway Department over the construction of Mound Road, claiming that the state had no jurisdiction to build the superhighway—"traversing 12¾ miles of farm lands and garden patches"—or impose tax assessments which "in many instances [were] larger than the actual values of the land." ("Million dollar Mound road tax levies declared void." Detroit Free Press, Oct. 11, 1933.) In his opinion siding with the plaintiffs, Judge Neil E. Reid of the Macomb County Circuit Court wrote:

It is evident that a highly speculative real estate improvement was here in progress and that the whole design of this highway, as carried on by the State Highway Department, was for the speculative purpose of developing farm lands for subdivision purposes. This is an honest statement of the purpose, and such action should not be looked upon with favor by the courts. The subsequent collapse of the real estate market merely proved the fact, which even at the time must have been self-evident, that these supposed benefits for which these lands were being assessed were merely the benefits which it was hoped in the future the lands would receive when a continued expansion of the City of Detroit should require their use. [...]

The State Government therefore finds itself in the position of causing that these land owners in general, for practically all of the entire 12¾ miles, shall lose their lands and forfeit them, because the State Government made the blundering determination that they were being immensely benefited by this project.

(Altermatt V. Dillman, 269 MICH 177 (1934))

A Detroit Free Press editorial asked, "If this was the case with Mound Road, how was it with Eight Mile Road, and the other highways developed in this fashion?" ("Mound road." Editorial. Detroit Free Press, Oct. 14, 1933.) Judge Reid ruled that the Mound Road tax assessments were void. However, this decision was later reversed.

Constuction had begun for an overpass to carry Eight Mile Road traffic over Telegraph Road as seen here, facing west along Eight Mile Road, August 28, 1930.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 26)

The Eight Mile Road overpass as seen from

Telegraph Road facing north, September 11, 1931.

(Archives of Michigan, Wayne County Road Commission photograph collection, Box 27 Folder 27)

Conclusion

The mile road system has unmistakably altered the landscape around Detroit. Without this vast network of concrete roads virtually serving as a blueprint for suburban sprawl, this region couldn't have become the world's first automobile metropolis. Drivers have daily reminders of the optimistic plans of our almost utopian traffic engineers in the form of the extra-spacious superhighways' notable green, grassy medians standing in place of the rapid transit rail lines originally envisioned by their designers a century ago.

Although early Depression-era taxpayers were experiencing sticker shock after paying for "the greatest highway system ever planned and built by man," this memory would fade as the economy recovered and automobiles once again filled city streets to capacity. As detailed in a previous article about the history of the Davison Freeway, by the 1940s the automobile industry had successfully convinced American taxpayers to go all-in on subsidizing a transportation system designed to serve and promote motor vehicles and related products.

An unexpected development of automobile-centered design is the strange erosion of differences between "streets" and "roads." Once upon a time, roads were high-speed thoroughfares which connected two or more population centers; and streets were human-scaled environments within villages and cities where people built homes, businesses, etc. A typical suburban commercial street in the US today is neither a street nor a road, but a "stroad." (This term was coined by the nonprofit organization Strong Towns in order to describe this economically unproductive development pattern of combining high-volume, high-speed roadways with commercial centers.) Woodward Avenue and Eight Mile Road, as rebuilt in the 1920-1930s, may be America's very first "stroads."

(StrongTowns.org)

The systematic hard-paving of section line roads, once a novel solution to a local transit problem, is now taken for granted as part of the standard land development pattern in North America. Most of the United States west of the Appalachian Mountains have been surveyed into square-mile sections according to the US Public Land Surveying System, supplying a convenient template for an endlessly repeating grid of automotive highways and suburban real estate development surrounding countless American cities.

As the future unfolds, we may learn to make better use of our public corridors, serving more diverse and efficient forms of transportation. How fortunate metropolican Detroit is to already have existing roadways with enough right-of-way for trains—should we ever agree on how to pay for them. Until then, let us at least start with a few bike lanes, since it was the work of bicycle enthusiasts like Horatio Earle and Edward Hines that paved the way for our road network in the first place.

This 2021 illustration shows an alternate configuration for utilizing Woodward Avenue's 204-foot right-of-way, which was implemented in 2023.

(FerndaleMoves.com)

"Had anyone prophesied [in 1906] that in 20 years there would be one motor vehicle for every three persons in Wayne County, or dared to suggest the plan which is now being carried out, he would have been accused of owning an opium pipe or, at the very least, of having the fantastic imagination of Baron Munchausen." —Edward N. Hines, County Road Commissioner, Wayne County

("Super-highways in Detroit region." Municipal and County Engineering, June 1927.)

(Image: Archive.org)

It's nice to see you back in business. I was always curious about one of the superhighways that never made it called SUNSET. Although there are some remnants that still bear the name going through Oak Park, Southfield and Lathrup Village.

ReplyDeleteI'm a little late to this, but I have some leads for you. Sunset was pitched as essentially another Northwestern, but running from 8 Mile near Palmer Park out to Wing Lake in Bloomfield. It was a pet project of Louise Lathrup.

DeleteGoldengate was going to be part of the Imperial Highway right-of-way, and I believe their oil pipeline ran under the median for a while, as it did along the right-of-way in Redford. It has since been moved.

Paul, off topic, but do you think you could do a on Springwells Township? I was recently trying to make sense of the northern border of the former village of Woodmere (incorporated in 1901) in its boundaries going through old Free Press articles online, but they had conflicting information. Or rather, the info from 1901 mentions discussion before incorporation (which appears to have happened in late July 1901) about the boundary, and then doesn't really mention them again. And then in 1906, partial boundaries are mentioned again as it relates to the Detroit annexation, but because it included additional parts of Springwells Township, you don't get a clear description of the northern boundary, either.

ReplyDeleteI think the northern boundary was Baby Creek from the Rouge River, then northeast along the creek to the western line of a private claim just east of Lonyo, and then north along that line to the Michigan Central Railroad corridor, and then east along that corridor to the old Detroit city limits. But an Free Press article from 1906 mentions creating three election districts for the annexation election, and mentions that Delray and Woodmere would be unchaged, but then describes the remainder of Springwells that would have the northern boundary of Woodmere differing.