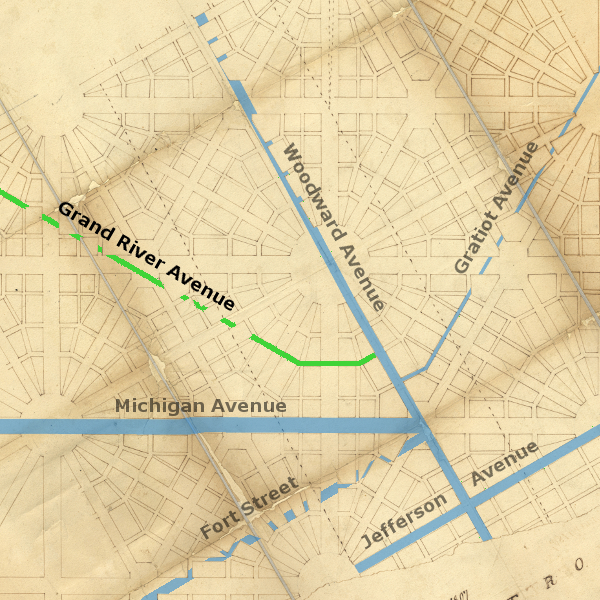

Grand River Avenue, the fifth radial avenue to be extended from Detroit, was built to connect the city to the point where the Grand River flows into Lake Michigan. Like Gratiot Avenue, this road roughly follows the same angle as some of the avenues in Augustus Woodward's Plan of Detroit, but it was not actually built where any main avenue was planned.

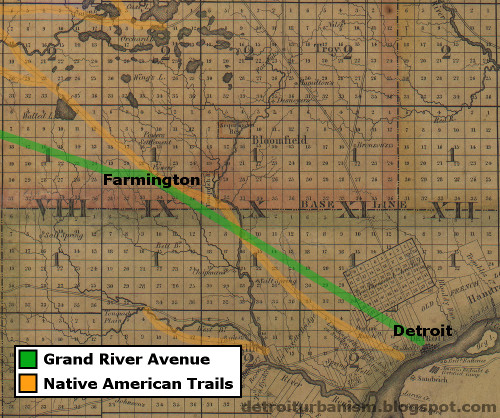

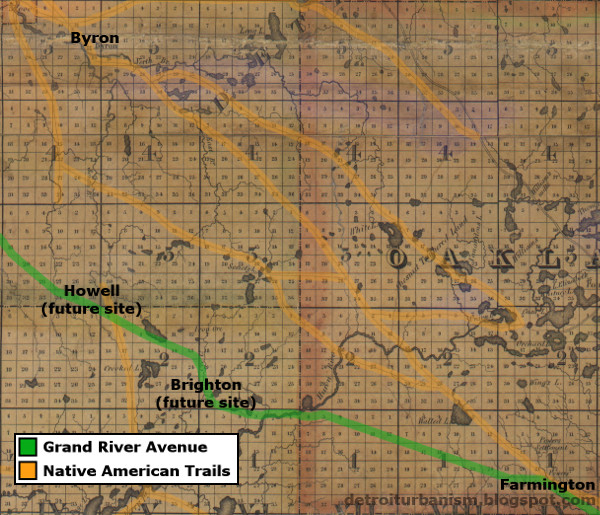

It is often said that Grand River Avenue was built over an old Indian trail. Although that claim is unproven, several causes for this belief can be found. First, there was an Indian path called the Grand River Trail, but it was located farther north in the state. Second, Grand River Avenue does barely coincide with the Shiawassee Trail for the first sixteen miles or so. This situation is similar to Woodward Avenue, which replaced the Saginaw Trail as the main route between Detroit and Pontiac even though one was not built on top of the other. Grand River Avenue's relationship to the Shiawassee Trail, at least between Detroit and Farmington, is similar. Below is a detail from Orange Risdon's 1825 map of southeast Michigan, with Native American trails highlighted, and the future path of Grand River Avenue added.

Perhaps the main reason for the idea that Grand River Avenue used to be an Indian trail might be the first petition that called for the road. On October 7, 1825, citizens of the Michigan Territory petitioned Congress to survey and build "a good road leading from Detroit to the Seat of Justice of Shiawasee [County], following as near as may be the Trail or Indian path." The seat of justice of Shiawassee County in 1825 was the Town of Byron, which did lie on the Shiawassee Trail beyond Farmington. But this is not where today's Grand River Avenue lies.

On December 15, 1825, the Michigan Territory's delegate to the House of Representatives, Austin E. Wing, responding to the petition mentioned above, introduced a motion that "the Committee on Roads and Canals be instructed to inquire into the expediency of laying out (a road) from Detroit to, or near, the mouth of the Grand River, by the way of the Quaker Settlement [Farmington] and Sciawasse."

The House of Representatives, over the next several sessions, passed bills to establish this road, but the Senate failed to approve them. The people of Michigan petitioned Congress again on June 16, 1831, and yet again on October 25, 1831, urging the legislature to act. Finally, on July 4, 1832, Congress passed "An Act to authorize the surveying and laying out a road from Detroit to the mouth of Grand river of Lake Michigan." The law authorized the President of the United States to appoint commissioners to "explore, survey, and mark, in the most eligible course, a road from Detroit, westwardly, by way of Sciawassee, to the mouth of Grand River." According to the law, these commissioners were to be paid $3.00 per day while working on the survey, and their assistants $1.50 per day, not to exceed $3,500. The survey was to be submitted to the president for approval.

The Survey

The three commissioners appointed for the project were Joseph White Brown, James J. Godfroy, and Lowrin Marsh. Godfroy and Marsh were prominent citizens of Monroe, and both of French Canadian descent. Brown, the trained surveyor of the group, was a character of notable intelligence and accomplishment. He was a founder of the village of Tecumseh, the first judge in Lenawee County, a General in the US Army, and was the commanding officer of US forces in Michigan during the Black Hawk War, which occurred immediately before the survey of the Grand River Avenue. General Brown would go on to play a role in the "Toledo War," operate a stage coach line between Detroit and Chicago, and serve as a regent of the University of Michigan.

A handwritten copy of General Brown's preliminary report to Lewis Cass, who was by then the US Secretary of War, is preserved at the Burton Historical Collection of the Detroit Public Library. The letter implies that President Andrew Jackson had delegated the power to appoint the Grand River Road commissioners to Secretary Cass. The report began:

Having been appointed by your honor under the act of Congress passed July 4th 1832 to authorize the survey and laying out a Road from Detroit westwardly by way of Schiawassee to the mouth of Grand River of Lake Michigan in the Territory of MichiganThe deadly cholera epidemic that was ravaging Detroit had arrived at the city on July 4, 1832, the same day as the passage of the Grand River Road act. On that day, a steamer, the Henry Clay, stopped in the city carrying infected soldiers from the Black Hawk War. One of the soldiers died the following day, and the ship was ordered away from the Detroit docks. But by then the disease had already spread to the civilian population. Ninety-six people died from cholera in Detroit that year, including Father Gabriel Richard, who succumbed to the illness on September 13, two days before General Brown and his crew left the city.

Would beg leave to report that on the 15th day of Sept. last we met in the City of Detroit not considering it prudent to commence our work at an early day on account of the chollary [cholera] that was raging in the city and the general unhealthy state of the country...

General Brown continued:

We left the city on our randum (sic) line Equal distance from the Chicago and Saganaw Roads and ran in a westwardly direction through a part of Oakland, Washtenaw & Schiawassee to the head waters of Cedar river thence down said River and Grand River to near the Rapids on the latter, from this line we explored the country from 10 to 20 Miles on each side of our Road and gathered all the information in our power, previous to establishing any part of said Road.A "random line" is when a surveyor draws a path aimed at a particular point, guessing the correct direction as best as they are able, and staking out the path with only temporary markers.

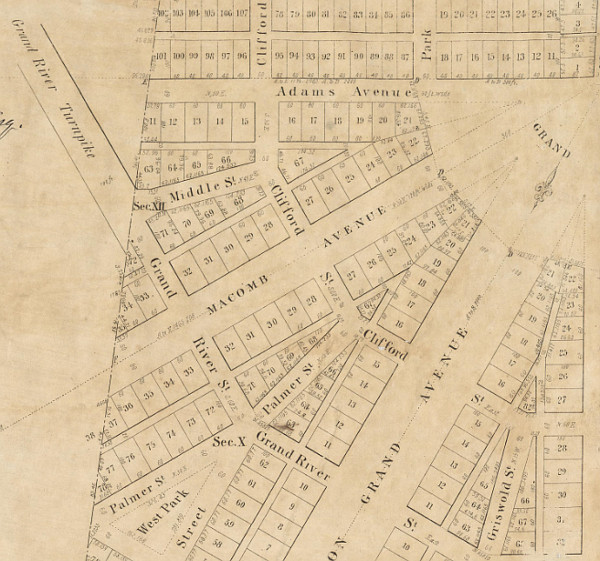

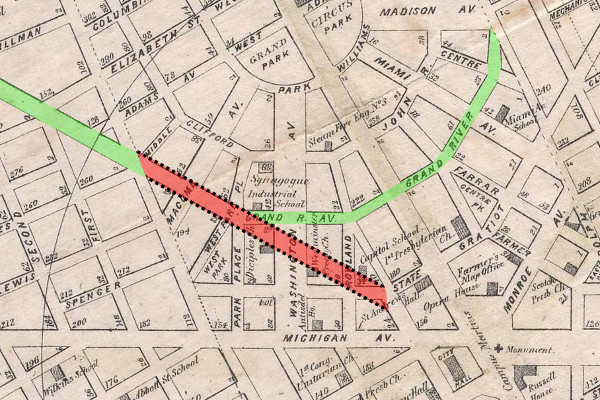

General Brown's report does not give the exact point of beginning of his survey, only stating that he began at an equal distance between Michigan and Woodward Avenues, which he referred to as "the Chicago and Saganaw Roads." Placing an avenue here was at odds with the Woodward Plan. Had General Brown wished to comply with it, he would have made the the new road an extension of Miami Avenue (now called Broadway) through the Grand Circus. But because a swamp occupied the Grand Circus area at the time, and because the population of the city was concentrated near the river, it was more convenient to begin the Grand River Road as an extension of a side street that dead-ended at the city limits, as seen below in a detail from surveyor John Farmer's 1835 map of Detroit:

Aside from its location, General Brown's road further violates the Woodward Plan in the angle at which it leaves the original city limits. According to the plan, such an avenue should have followed a bearing of N 60° W, but today's Grand River Avenue bends slightly at Cass Avenue to an angle of N 61° 6' W. It follows this direction for approximately seventeen miles before making its first bend in what is now Farmington Hills.

It's not clear why General Brown's team "explored the country" once they reached western Michigan, other than to avoid the cholera epidemic. And there is no indication of how long this exploratory portion of the job lasted. In any case, "immediately on our return" to Detroit, wrote General Brown, "we commenced laying and marking the Road in the most permanent manner."

General Brown's account describes the natural landscape along the route, noting that the first twenty-nine miles are heavily timbered. The following thirty-one miles (more or less within present-day Livingston County) was "an open country (with) dry sandy soils, interspersed with lakes, hills & prairies, being the head waters of the Rivers Huron, Shiawassee, and Grand River and the highest land in Michigan." From there they headed west to the Red Cedar River, which they followed until it met the Grand River. The confluence of the Grand and Red Cedar Rivers was located in an unincorporated township that, fifteen years later, was to become the state's capital: Lansing.

After crossing the Grand River, the surveying team "ran down on the right bank and between the Grand and Looking Glass Rivers to the Indian village of Shimnacons." This village, located in what is now Danby Township, is mentioned in a description of the Grand River in a travel guide published the following year:

Four miles above the mouth of the Looking-glass River is the village of P'Shimnacon (Apple Land), which is inhabited by eight or ten Ottawa families, who have a number of enclosed fields, in which they raise corn, potatoes, and other vegetables usually cultivated by the Indians. The village receives its name from the Pyrus coronaria (Crab Apple) which grows in great abundance on the rich bottoms of the vicinity. [This land] has been ceded to the United States, and will, no doubt, in a short time, be occupied by an industrious white population. There is a large trail leading from this village, by way of Shiawassee to Detroit, a distance of 130 miles.After passing through the village and reaching the center of Ionia County, the team headed west and roughly followed the Grand River to the point where it empties into Lake Michigan. "The whole distance from the city of Detroit to the Mouth of Grand River," wrote General Brown, "we find to be 177 Miles, and in the above sketch we have given you the outlines of the rout (sic) we have located, in order that you may advisably lay the subject before the President."

The location of the Grand River Road, surveyed in 1832.

A More Northerly Route

A plat of the road was sent to Washington, where it met President Jackson's approval. However, not all citizens of the territory were pleased.

In the winter of 1833-1834, 407 Michiganders signed a petition to Congress, complaining that the approved route was "laid through a heavy timbered country, and across many extensive marshes and cedar swamps and passing through no important places." They suggested an alternate route beginning at the Grand River Road's tenth mile post (in what is now Detroit's Grandmont-Rosedale neighborhood), then following a more northerly route above Walled Lake, farther up the Shiawassee River, and then "through the seats of Justice of the counties of Clinton, Ionia & Kent." The petition stated that this route "would pass through an open country well calculated for a road of that magnitude," be a "means of the settlement of the Grand River Country much sooner" and save "an immense expense in the construction of the road."

Sketch of the alternate path suggested by petitioners in 1833.

While this petition gained followers, an opposing one began to circulate as well. This remonstration, signed by 164 citizens of the territory, complained that many individuals have already purchased land along the route in good faith that the government would build a road according to the established survey. The petition is worth quoting at length:

Whereas your honorable body in Great wisdom and Goodness has been pleased to Decree a National Road running directly from the City of Detroit unto the mouth of Grand River or thereabouts in said Territory and as a proof of your parental kindness and love to Internal Improvement you have also caused the same to be surveyed and have made liberal appropriations for the opening and improvement of the same...A similar petition against the change gained fifty-nine signatures. Congress received all three documents, referring them to the Committee on Roads and Canals. However, no action was taken by the federal government to alter the survey.

Nevertheless certain individuals of the Towns of Southfield and Farmington living to the north of said Road being influenced by personal Interest and popular views and regardless of General Good have recently circulated a petition purporting their desire that your honorable body would make an alteration in the Survey of said Road and run it North of the present Route about a mile and a half so as to accommodate and monopolize them, and there to intersect the present survey some miles west of Arthur Powers present establishment [Farmington] which curve will lengthen the distance not far from three miles in Ten and all under the plausible pretext of bringing the Road on better Ground when in fact it is to the Reverse and in our candid opinion their fair speeches and zealous efforts which they are making is nothing more nor less than Duplicity which they are desirous of practiceing (sic) on your honest and innocent credulity.

Construction

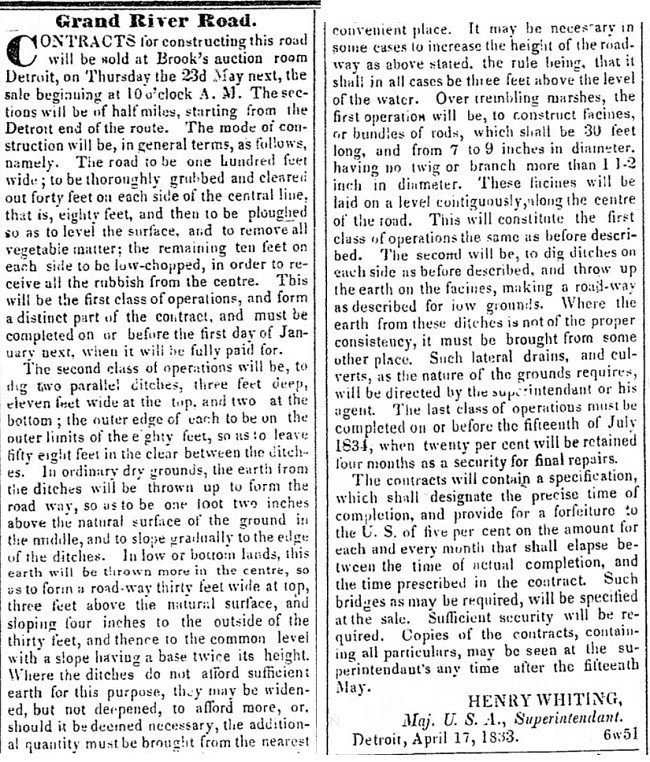

On March 2, 1833, Congress appropriated $25,000 to begin construction on the Grand River Road. On April 24, the superintendent of the project, Major Henry Whiting of the US Army, published an advertisement in the Detroit Free Press announcing the sale of contracts for the construction of the road. Private contractors were to bid for work on half-mile sections of the road on May 23, 1833. Details of the required method of construction were given in the ad, reproduced below.

Senator Thomas Palmer, who was born in Detroit in 1830, once recalled: "I can well remember the Grand River road, now the avenue of the same name, being cut through heavy timber from a point about Sixth street." Charles Gratiot, Chief Engineer of the US Army, reported to Congress on November 23, 1833: "On ten miles of this road the first class of operations, consisting of clearing and grubbing, excepting on one mile, will be completed by the close of the season." The full completion of this section--through flat land that was at the time prone to flooding--was delayed by setbacks ranging from a wetter than usual spring, to a second and more deadly outbreak of cholera.

No federal funds were granted for the road in 1834. But the following year, Congress appropriated an additional $25,000 on March 3, 1835. This was to be the last federal grant spent on the Grand River Road's construction. By January 1837, Michigan had achieved statehood and no longer received federal funding for roads. Most of the work on the Grand River Road until that point was confined to Wayne, Oakland, and Livingston Counties. Completing and maintaining the road across the peninsula would require a combination of state funding and experiments in privatization.

The Detroit & Howell Plank Road

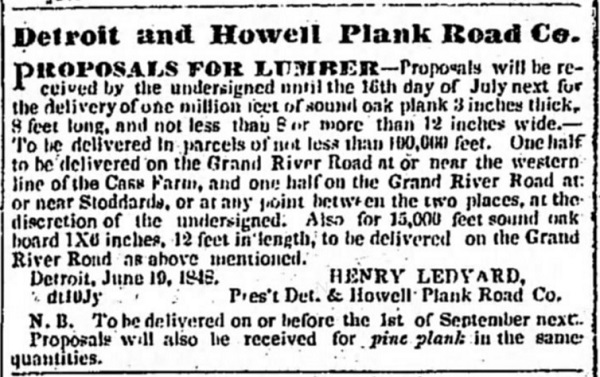

When Lansing Township became the new capital of Michigan on December 1, 1847, the need for improved roads between the state's seat of government and its largest settlements was obvious. Rather than tax the general population, the state government granted charters to privately owned companies, allowing them to build wooden-planked highways and charge tolls for passage. One of these entities was the Detroit and Howell Plank Road Company, chartered on April 3, 1848, which was permitted to make use of the Grand River Road from Woodward Avenue in Detroit to Howell Township, the seat of Livingston County.

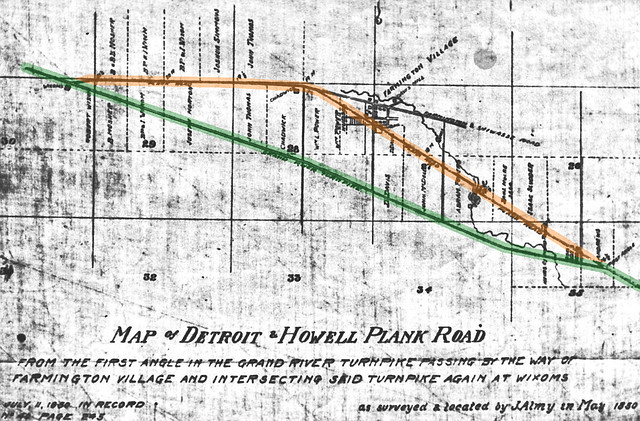

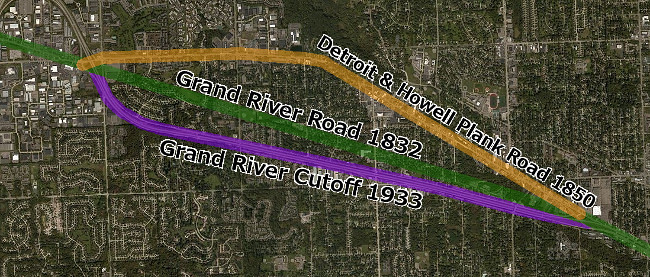

Before the Detroit and Howell Plank Road Company, the Grand River Road did not pass through the unincorporated village of Farmington. Farmington's main street at the time was Shiawassee Road, the former Native American trail. The company hired surveyor John Almy to plan an alteration in the Grand River Road that would bring it through the heart of the village. In May of 1850, Almy established a new route beginning at the first bend in the original survey, near what is now Tuck Road. The new line was drawn northwest from that point to intersect Shiawassee Road, then joining the line that would later become concurrent with Ten Mile Road.

The map below shows the original 1832 Grand River Road (highlighted in green) and the 1850 alteration made for the Detroit and Howell Plank Road company (highlighted in orange) as they passed through Farmington Township.

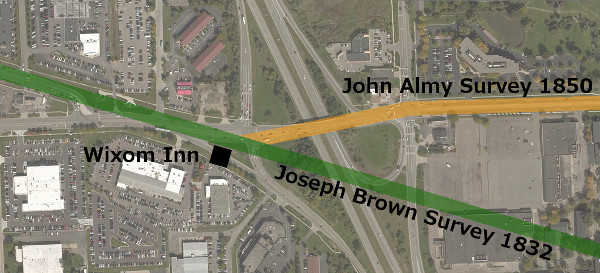

The western end of Almy's survey did not return to the original route by simply following the Ten Mile Road line on a straight path. Rather, it bends to the southwest first. This was done to accommodate the Wixom Inn, a roadside tavern that had been in operation on the original Grand River Road for years. According to historian John Willyard, this diagonal section of road cut through the property of Robert Wixom, who sold the sixty-six-foot right-of way to the plank road company on June 17, 1850. The Wixom Inn is long gone, but the bend in the road created for its sole convenience still exists.

The wood planks that covered eight-foot-wide center portion of the road held up just as poorly as one would expect. By some accounts, the planks were removed and replaced with gravel as early as 1858. The Detroit and Howell Plank Road was so poorly maintained that the City of Detroit took over the paving of the road inside of the city limits long before gaining ownership of the right-of-way in the 1880s.

By the 1920s, when automobile traffic had grown exponentially, civil engineers called for an express route on Grand River Avenue that would bypass downtown Farmington. The "Farmington Cutoff" or "Grand River Cutoff," now called Freedom Road, was completed in 1933, first operating as a one-way road accommodating eastbound traffic only. Oddly enough, it roughly replaces the portion of the original 1832 Grand River Road that was removed when the plank road was built.

"Straightening" Grand River Avenue

Like Gratiot Avenue, Grand River Avenue does not extend directly from the center of the city, but begins as a narrow side street that meets Woodward Avenue. Farmers bringing their produce into the city by way of Grand River Avenue either congested the sixty-foot right-of-way or turned down various side streets to reach city markets. In 1874, the city council considered a plan to correct this awkward placement by widening Grand River Avenue by twenty feet between Cass Avenue and Park Place, and then continuing the eighty-foot-wide road straight through to Griswold Avenue. City planners were attempting to settle problems foreseen by Augustus Woodward nearly seventy years before--problems that would not have arisen had the Woodward Plan been followed all along.

Citizens speaking for and against this plan attended a special meeting of the Detroit City Council on June 10, 1874. However, the committee tasked with examining the subject declined to recommend the scheme. An alternative suggestion, to widen the existent route of Grand River Avenue to 100 feet, was also rejected.

Proposals to straighten Grand River Avenue would resurface from time to time. The city council again debated the topic throughout the spring of 1891, but those discussions went nowhere. The idea was revived ten years later, but when the city council held an open meeting on the topic for any interested citizens on December 26, 1901, nobody showed up.

Thankfully, the project never gained enough support to further injure the Woodward Plan. As far as the rest of Grand River Avenue, the path now followed is mostly unchanged since the days of the Detroit and Howell Plank Road (other alterations farther west in the state notwithstanding). A complete history of Grand River Avenue in the twentieth century can be found on the excellent website MichiganHighways.org.

My grandparents lived in Farmington on Randall right beyond where Grand River forks into M-5

ReplyDeleteNicely explained the historical point of view in this post and the grand river post information is also great. jfk short term parking deals

ReplyDeleteLived 8 mile / Telegraph area from 1956 to about 1976... I remember an old man that lived on Grandview Street who told me that Shiawassee was the "first road" in our neighborhood, even before Grand River went in...But he did say "That is what I heard". He was right, but Shiawassee wasn't a road, it was an Indian trail. You can literally access any Detroit map, and where Shiawassee and Grandview meet get a ruler, draw a straight line and can SEE how it used to traverse right into downtown Detroit.

ReplyDelete