(The Henry Ford)

This is Part Three in a series covering the historical development of the City of Highland Park. Part One documents the original village's founding by silver baron Captain William H. Stevens as an exclusive community, real estate enterprise, and tax haven for the wealthy. Part Two begins with the arrival of the Ford Motor Company, which exercised powerful influence over the local government, most notably in obtaining a state-of-the-art independent waterworks, built chiefly to satisfy the factory's need for 30 million gallons of water per day. This installment begins in 1918, just after the Village of Highland Park was incorporated as a city.

Highland Park's First Mayor

Royal Milton Ford

(Find a Grave)

Highland Park became a city on April 4, 1918. Royal Milton Ford, the former village clerk who was born and raised in the area (but not related to Henry Ford), was sworn in as the city's first mayor four days later, his candidacy having been endorsed by none other than Henry Ford himself. ("Politics seething in Highland Park." DFP, Feb. 23, 1920.) Mayor Ford was evidently uninterested in either family life or a career outside of Highland Park's municipal government. Following the election, he remained living with his mother at the family homestead at 2999 Woodward Avenue (later renumbered as 13945 Woodward). On one occasion when Mayor Ford was out on business, the city council facetiously passed a 25 percent "celibacy tax" on all "bachelors," poking fun at city's chief executive. The Detroit Free Press reported that Mayor Ford, "who still enjoys celibacy, ruled the measure out upon his return on the ground that it was class legislation." ("Celibacy tax balked by bachelor mayor." DFP, Aug. 27, 1918.)

Mayor Royal Milton Ford's World War I draft registration card, September 1918.

(Ancestry.com)

Mayor Ford was soon about to enjoy a lifestyle change. In May 1919, Arthur and Julia Daniels of Avalon Street announced the engagement of their 22 year old daughter, Gladys Lucile, to the Mayor of Highland Park. According to a news story, the "pretty little romance" had already begun when Ford was village clerk, and Miss Daniels performed clerical work for the village treasurer's office. ("Suburban mayor will wed in June." DFP, May 10, 1919.) They were united in marriage by James D. MacDonald, pastor of the Highland Park Presbyterian Church, at the bride's home, 110 Avalon Street, on June 25, 1919. Highland Park councilman Martin B. Hansz acted as Ford's best man. ("Highland Park girl becomes bride of Mayor Milton Ford." DFP, Jun. 29, 1919.) Following their honeymoon road trip to New York and Atlantic City, the couple made their home at 33 Ford Street.

110 Avalon, the home of the City of Highland Park's first "First Lady," Gladys Lucile (Daniels) Ford, whose parents moved here around 1909.

(Google Street View)

A Massive Building Program

Highland Park was in the process of overhauling its new waterworks system in order to keep up with the demands of the Ford Motor Company when it reincorporated as a city. The new 45-million-gallon reinforced concrete reservoir was officially put into service on April 4, 1918, the same day that Highland Park ceased to exist as a village.

The northern end of the Highland Park Waterworks reservoir, circa 1920.

(Virtual Motor City)

Water shortages experienced in the summer of 1918 were relieved when two new pumps installed at the Davison pumping station greatly improved the city's water pressure. Repairs were also made to the reservoir, which was found to have been leaking one million gallons per day. ("New pump ready in Highland Park." DFP, Aug. 7, 1918.) The ongoing World War delayed construction of the anticipated filtration plant, which required the approval of the War Industries Board before construction could begin. Meanwhile, since the engineers who designed the plant left the type of filter bed material to be decided by the city, Mayor Ford brought councilmen Martin B. Hansz and Frank T. Lodge on an tour of municipal filtration plants in eastern and midwestern cities to gather relevant information. ("Mayor reports bonds' refusal." DFP, Oct. 1, 1918)

Aerial view of Highland Park's water reservoir, facing east, circa 1920. The church on the lower right stands at 13580 Orleans Street.

(Virtual Motor City)

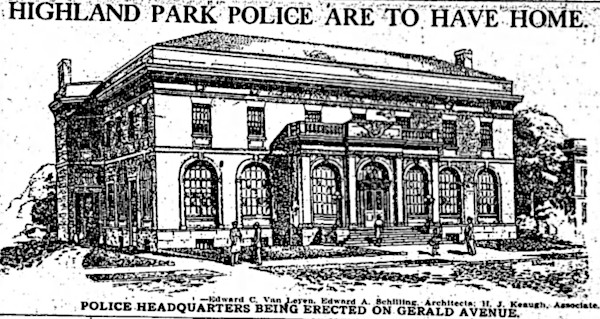

By the fall of 1918, the Highland Park police had moved out of the old municipal building on Gerald Street and into a new police headquarters just across the street. The "modernized renaissance" style building was designed by architects Edward C. Van Leyen and Edward A. Schilling, and built by the Warswick Brothers construction firm. ("Police station is being built." DFP, Oct. 7, 1917.) The original municipal building, constructed six years prior, was renovated following the move of the police department.

(Newspapers.com)

The end of World War I in late 1918 meant the anticipation of relief in the years-long shortages on labor and building materials. When the Detroit Building Trades Council urged Highland Park to engage in as much construction work as possible to keep laborers employed, the city replied that 1919 would see the biggest construction program in Highland Park's history. Projects planned for that year included four miles of trunk sewers, a municipal hospital, and the waterworks' filtration plant and new pumphouse. ("Highland Park plans big building program." DFP, Dec. 18, 1918.) One project that happened to be wrapping up at that time was the new second unit of the Highland Park High School, completed in December 1918. The massive stone building, designed by Highland Park architect Wells D. Butterfield, was two blocks long and had cost nearly $3 million (about $56 million today) since the cornerstone of the first unit was laid four years prior.

Highland Park High School, constructed between 1914-1918.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Wells D. Butterfield, architect of the Highland Park High School, lived at 66 Glendale Avenue with his wife and two adult children, including Emily Helen Butterfield, the first woman in Michigan to hold an architecture license.

Men were at work at the site of the new filtration plant by the spring of 1919. The city's superintendent of public works, Elmer C. Foster, reported a delay when the laborers went on strike for $5 a day, a rate which the city council later approved. ("City wage raised in Highland Park." DFP, Jun. 10, 1919.) When these workers later demanded $7 a day, the city sought the help of Black laborers, evidently expecting them to work for less. Highland Park's city council spent $900 on railroad tickets to transport 52 Black workers from Saint Louis in order to finish the filtration plant. According to a Detroit Free Press report, "20 left after one day's work, and the remaining 32 are extremely dissatisfied with their pay and working conditions." ("Importing Negroes found expensive." DFP, Jul. 29, 1919.)

(Newspapers.com)

Despite the tone of that article, Black laborers seemed to be the only individuals willing to fill the jobs at the public works site. John Pappas, a Detroiter whose house on Saint Aubin Street backed up to the property, sued Highland Park, not just because of the presence of the reservoir, garbage plant, incinerator, and stone crusher, but also because, as a Free Press report puts it: "the city has ... engaged a number of Negro attendants for the garbage plant (and) permitted the Negro helpers to sit up late at night, singing plantation melodies and concert hall songs." ("He wants city to please go away and leave him alone." DFP, Aug. 28, 1919.) Apparently no injunction was granted.

Because the waterworks site had been annexed by Detroit in 1916, Highland Park had to obtain building permits from its neighbor city in order to begin construction. The Detroit building department issued the permit for the filtration plant, estimated to cost $25,000, on August 6, 1919. Highland Park later obtained a permit to rebuild and expand the pumphouse, a job costing approximately $15,000, on September 12.

Building permit for the City of Highland Park's water filtration plant.

Building permit for the City of Highland Park's water filtration plant.(Image courtesy Rebecca Binno Savage, Architectural Historian)

That autumn saw the opening of Highland Park's first city library in the fieldstone house built by Captain Stevens in 1893. Philanthropists Tracy and Katherine (Whitney) McGregor, who had purchased the home in 1905 to raise their large family of adopted children, donated the land to the city on July 8, 1918. The gift came with certain conditions, including requiring the city to construct, maintain, and landscape a new building on the site within five years of the end of the ongoing World War. ("Land for library given to suburb." DFP, Jul. 9, 1918.) In the meantime, the house was transformed into a library and opened to the public following dedication ceremonies on October 11, 1919. The city named its newest institution the Katherine McGregor Library.("Highland Park's library is ready." DFP, Oct. 6, 1919.)

A photograph of the original McGregor Public Library from the October 6, 1919 edition of the Detroit Free Press.

(newspapers.com)

Progress on the city hospital—planned to be staffed by Highland Park residents and prioritizing Highland Park patients—came steadily but slowly. The city entered into a contract with Chicago architect Meyer J. Sturm in January 1919 to design the structure. Funding the project required voters to approve bond issues on three separate occasions: $250,000 in 1917, $200,000 in 1918, and a final $200,000 approved on November 1, 1919. ("$200,000 is needed for new hospital." DFP, Oct. 25, 1919.) After many delays, Highland Park General Hospital would finally open in April 1921.

(Newspapers.com)

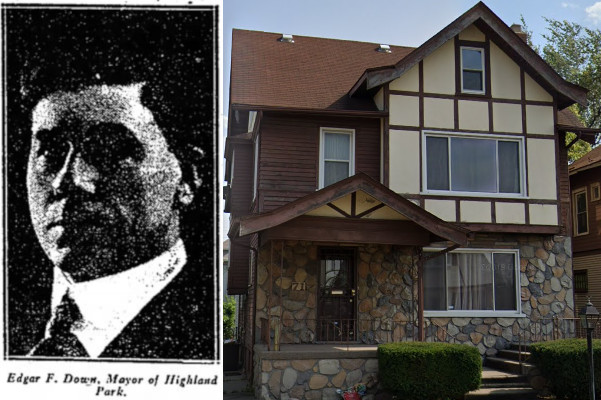

(Newspapers.com)Highland Park's Second Mayor

Mayor Royal M. Ford filed to run for reelection soon before the expiration of his first term in early 1920. However, he would not be running unopposed. Three others were vying for the same position: Edgar F. Down, principal of the Willard School; Oscar A. Janes, a city councilman; and Martin A. Martin, a former village president. Janes' candidacy was somewhat controversial, as he and Royal Ford had been allies, both having received Henry Ford's endorsement for their respective positions in the previous election.

At the primary election on March 3, 1920, incumbent Ford placed third in the race. He would not move on to the general election—in fact he never sought public office again. Edgar F. Down won the most votes in the mayoral primary, despite never having run in an election before, and being the only contestant not previously affiliated with the Ford Motor Company. After Down and Janes progressed to the April 6 general election, Down was victorious with 4,315 votes to Janes' 3,092. ("Non-partisans in ascendancy." DFP, Apr. 7, 1920.)

Edgar F. Down and 71 Waverly Pl., the home he lived in when elected mayor.

Edgar F. Down and 71 Waverly Pl., the home he lived in when elected mayor.(freep.newspapers.com)

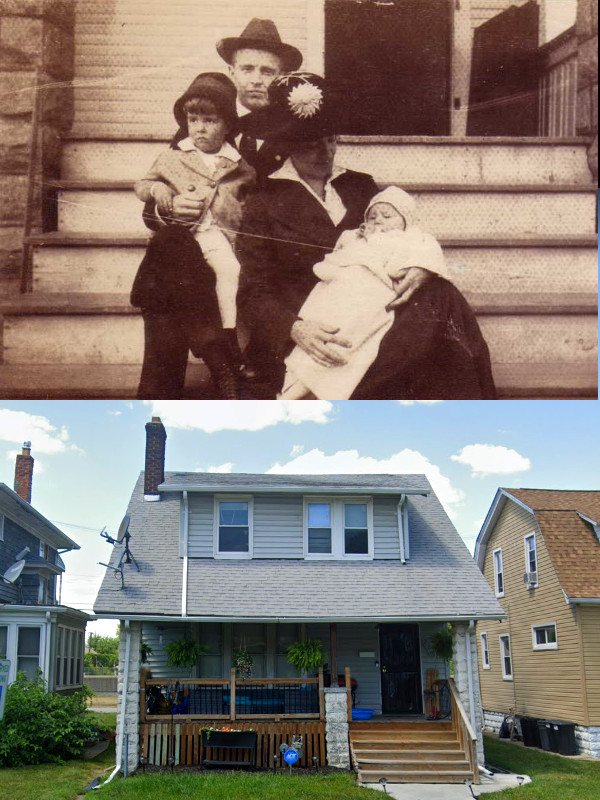

On the same day as Down's victory, the voters of Highland Park elected a socialist to their city council. Irving Paul Taylor, formerly a minister at the Highland Park Congregational Church, would later that year publish Prosperity in Detroit, a short book exposing housing and labor conditions in the city and suburbs, in contrast to the rosier pictures of the region's "wealth" being published at the time.

Top: I. Paul Taylor and his wife, Josephine, and their children, Guilford and Paul. Image courtesy Ancestry.com user Michael Marsh. Bottom: 226 Waverly Place, Taylor's home when elected to Highland Park's city council in 1920. Image courtesy Google Street View.

Top: I. Paul Taylor and his wife, Josephine, and their children, Guilford and Paul. Image courtesy Ancestry.com user Michael Marsh. Bottom: 226 Waverly Place, Taylor's home when elected to Highland Park's city council in 1920. Image courtesy Google Street View."We'd have to scratch our heads to think of any new ways to spend money."

Highland Park's grand municipal building projects made it the envy of municipalities across the nation. "When Highland Park people begin drinking filtered water," Mayor Down told a Detroit Free Press reporter, "we will have one of the most complete cities of our size in the country. And when our hospital is in operation ... I really believe we will be the most complete." He added, "Give us a nurses' home, a new contagious hospital and a new city hall and we'd have to scratch our heads to think of any new ways to spend money." ("Hail to Highland Park---a city within a city." DFP, Sep. 26, 1920.) The desired amenities mentioned by the mayor (nurses' home etc.) would all be added by the end of the decade.

This illustrated article in the September 26, 1920 edition of the Detroit Free Press celebrates the marvelous construction projects occurring in Highland Park.

(newspapers.com)

The city's long-anticipated filtration plant went into operation at a "soft opening" on the morning of November 13, 1920, dramatically improving the quality of municipal water. (Not even Detroit enjoyed filtered drinking water yet, although a filtration plant of its own was soon to be constructed.) A formal opening of the new waterworks followed on December 4, when the public was invited to inspect the facility's improvements and additions. An engineering trade publication from the time made this description of the interior decorations:

Considerable money has been spent in beautifying the interior of the building in order to make a pleasing impression on visitors to the plant. The entrance hall is trimmed in gum wood, with mahogany finish, has tile floor trimmed with polished marble, ornamental iron stair railings, bubbling fountain, ornamental light fixtures and other features. Broad marble stairs lead up a height of nearly 4 ft. from this entrance hall to the filter gallery, which is furnished with polished marble operating stands and has a background formed by the white enameled brick walls of the filter house.

("Water purification plant at Highland Park, Michigan." Engineering News-Record, May 5, 1921.)

Highland Park's water filtration plant headhouse, constructed 1919-1920.

A new brick pumphouse, constructed on the same spot as the original, appears on the left hand side in the image below. What appears to be a grassy hill on the right is actually the original reservoir, which was converted into a covered coagulation basin as part of the waterworks upgrade plan. Water from the new 45,000,000 gallon reservoir flowed into this coagulation basin, where alum was added in order to remove solids.

After leaving the coagulation basin, water was then filtered through 30 inches of sand and 18 inches of gravel. In order to obtain just the right filtration materials, the sand had been imported from Cape May, New Jersey and Red Wing, Minnesota. Following this process, the water was then stored in a 4,000,000 gallon clear water reservoir located beneath the filtration plant. Chlorine gas was added to the water before it was finally pumped to Highland Park water customers.

"City of Highland Park Filtration Plant Concrete Encasement for 16" C. I. Drain."

(Detroit Historical Society)

"It is estimated that the capacity of the present plant is sufficient to care for a city of 65,000 people," the Detroit Free Press noted, "this probably being the minimum [sic] who could be crowded into the territory of the city, which now has 46,000." ("H.P.'s filter plant viewed." DFP, Dec. 5, 1920.)

(Archive.org)

When Highland Park first began drawing its water supply from Lake Saint Clair in 1914, it had entered into a ten-year contract with Detroit Edison and the City of Grosse Pointe Farms regarding ownership and operation of the lakeside pumphouse property. When that agreement expired, Highland Park had the opportunity to purchase the pumphouse and equipment, which it did. As part of the new contract, signed August 14, 1924, Highland Park became owner of an 88.04% share of the infrastructure which lay beyond the shoreline (the water crib, intake pipe, and well house). Grosse Pointe Farms obtained an 11.96% share in that property, as well as a vacant portion of the pumphouse lot, where a filtration plant for the Grosse Pointes was constructed several years later. To this day, Highland Park retains full ownership of the original pumphouse located at 337 Lake Shore Drive in Grosse Pointe Farms.

337 Lake Shore Drive, Grosse Pointe Farms.

Property of Highland Park since 1924.

(Google Street View)

The McGregor Public Library

Katherine McGregor's donation of a library site to Highland Park came with the condition that the city replace Captain Stevens' old fieldstone house with a new building "not inferior to the Henry M. Utley Branch Library in the City of Detroit" within five years of the end of the World War. The city officially accepted the donation on July 8, 1918. The following year, the council passed an ordinance creating the McGregor Public Library Commission, on March 10, 1919. Although the construction deadline was extended, by the autumn of 1923 the commission was actively selecting an appropriate design. According to a history of the library printed in a program printed for the dedication ceremony, "It was the unanimous feeling of the (Highland Park Library) Commissioners that they should not be limited to the cost of the building which had been named in the McGregor deed as a standard (the Utley Branch Library), but that something entirely worthy of the modern city of Highland Park and its progressive citizens should be constructed." To construct the Henry M. Utley branch of the Detroit Public Library was estimated at the time to cost $255,000. The Highland Park Library Commission decided that their building should cost almost double that amount.

The library's design "follows the imperial classic style as used in Rome under the emperors," according to the Detroit Free Press of March 2, 1924.

The library's design "follows the imperial classic style as used in Rome under the emperors," according to the Detroit Free Press of March 2, 1924.(freep.newspapers.com)

Members of the library commission spent two weeks touring several eastern states, inspecting at least 25 libraries before concluding that the new McGregor Library should be based on the general design of the public library in Wilmington, Delaware. ("H.P. picks model for new library." DFP, Oct. 30, 1923.) Within a month, the city was entering an agreement with Edward L. Tilton and Alfred M. Githens of New York, the architects of the Wilmington Library. Coincidentally, Tilton had just completed a design for the Dearborn Township library, now known as the City of Dearborn's Bryant Branch Library. The commission also hired Marcus R. Burrowes and Frank Eurich, Jr. of Detroit as associate architects for the project.

(Detroit Historical Society)

(Detroit Historical Society)On February 24, 1924, Highland Park's city council approved placing a $500,000 library bond issue on the ballot at the upcoming election. Voters overwhelmingly approved the measure on March 5 by a vote of 2,356 to 822. ("Jezewski leads in Hamtramck." DFP, Mar. 6, 1924.) Early the next year, Highland Park's third mayor, Clarence E. Gittins, unveiled a "constructive program of civic improvements limited in scope only by the financial competency of the city," according to the Detroit Free Press. ("H.P. outlines improvements." Jan. 18, 1925.) Ground was broken for the new structure on February 7, 1925, and construction began twelve days later. The cornerstone was placed the following month at a ceremony held on March 28.

(Hathi Trust)

Two months after construction began, the library's architects were recipients of one of six medals awarded at a large architectural exhibition held in New York City by the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the Architectural League of New York. At a presentation on April 20, the "monumental medal," for public or institutional buildings, was awarded to Tilton and Githen for their work on the McGregor Library. ("Courtyards and tiled floors are latest thing in architecture as medieval design is revived." The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Apr. 21, 1925.) This event seems to have been misremembered as Tilton and Githen having received the AIA's Gold Medal, its highest honor, but their names do not actually appear in the list of recipients. Regardless, the library remains "one of the most attractive buildings of the classical persuasion in the Detroit area," as Detroit architectural historian W. Hawkins Ferry has declared The Buildings of Detroit: A History.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

The McGregor Library was officially dedicated on March 5, 1926, two years to the date from when voters approved the library bond issue. Yet the building was not quite complete, as the immense bronze entry doors had not even been designed yet. When the library first opened, the library commission was reportedly working with Chicago sculptor Lorado Taft to mold the doors' bas relief sculptures ("Highland Park plans dedication of library." DFP, Feb. 21, 1926.) However, later sources say the job ultimately went to Taft's associate, Fred M. Torrey. Before the design was finalized, the library commission had expressed the wish that "the main motif of these doors symbolize the automotive spirit which is the basis of the wonderful progressiveness of Detroit and Highland Park." The sculpted bronze figures which grace the library's entrance include a crouched male figure on the lower right, with eyes downcast and head bowed reverently to the a precious object in his hands—an automobile—that sacred invention which had brought so much wealth and prosperity to Highland Park.

Image courtesy Anthony Lockhart.

When Mayor Gittens announced the city's plans to build a new library and other projects in 1925, the Detroit Free Press remarked, "Financially, the city is proceeding on conservative lines. Most of the improvements mentioned will be cared for by bond issues, but the city's debts are only a small fraction of its rapidly improving assets." ("H.P. outlines improvements." DFP, Jan. 18, 1925.) The city was, after all, home to the one of the wealthiest and most influential corporations in the history of the planet to date. And it was obvious to everybody that Ford would always remain faithful to Highland Park, manufacturing an endless stream of automobiles, forever and ever, until the end of time.

May 26, 1927:

Model T Production Comes to a Screeching Halt

(Automobile Reference Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia)

The Ford Motor Company had been denying all rumors of a new Ford automobile for more than a year by the time the news finally broke on the evening of May 25, 1927. At the company's Dearborn offices, Ford officials announced that, after nearly twenty years in production, the Model T was finally going to be retired. ("New Ford car announced; details forthcoming soon." Ford News, Jun. 1, 1927.)

The news was evidently timed to coincide with another Ford milestone: the assembly of the 15 millionth Model T, which was to occur the following day. At around 3:30 P.M. on May 26, a newly completed vehicle whose engine had been stamped with the vehicle identification number "15,000,000" rolled off the assembly line at the Highland Park factory which had been the center of Ford automobile production since 1910. Henry Ford's son, Edsel, was the first person to drive the "last" Model T, with Henry in the passenger seat and longtime Ford executives Charles E. Sorensen and Peter E. Martin in the back. Accompanied by reporters and cameramen, the party left Highland Park behind, driving 14 miles through the cold spring drizzle to the company's Engineering Laboratory in Dearborn.

(thehenryford.org)

It was inevitable that Ford's Dearborn properties would rise in prominence above Highland Park. Moving materials in and products out of the landlocked factory wasted a lot of time and energy. Ford had spent nearly a decade building at the River Rouge in Dearborn new factory complex, which by this time was already manufacturing tractors. By November 1925, 70,682 workers were employed at the Rouge, surpassing for the first time the total at Highland Park, which had fallen to 51,533, even though the company was employing more workers than ever before. ("Employee total is highest in history." Ford News, Nov. 1, 1925.) The Highland Park plant's gas-steam generators—once cutting-edge technology—had become obsolete, as the gigantic new powerhouse at the Rouge began supplying the Highland Park plant with electricity in 1926.

Completed in 1916, Ford's power house consumed up to 30 million gallons of Highland Park municipal water each day, requiring the city to greatly expand its waterworks. By 1926, the power house was practically idle.

(Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University)

Retiring the Model T was a death blow to the Highland Park complex, but the end was inevitable. Both Ford's production figures and profits were significantly lower in 1926 than they were in 1925. The complex had succeeded in its one purpose: to flood the brand new automobile market with as many Fords as possible. By now, just about everybody who wanted and could afford a Model T had already got one. The Highland Park factory would temporarily serve other purposes, such as making spare parts for the Model T and some components of the new car, to be called the Model A—but not one more Ford automobile would be assembled at this plant ever again. The factory's innovative gas-steam generators (except one) and millions of dollars worth of equipment specially engineered for manufacturing Model Ts was now just a heap of scrap metal.

When the switchover from the Model T to the Model A was first announced, Henry Ford claimed "only a comparatively few men ... less than 25,000 at a time" would be out of work during a "brief" layoff. ("New Ford car announced; details forthcoming soon." Ford News, Jun. 1, 1927.) But the shutdown would actually last longer and put more people out of work than predicted. By August 1927, Chester M. Culver of the Detroit Employers' Association was point-blank warning unemployed individuals to stay out of Detroit. "If thousands of workmen come to the city with the hope of getting jobs they are bound to be disappointed," he said, claiming that 40,000 Detroiters were already "walking the streets in search of work." ("Labor ample for Ford need." DFP, Aug. 6, 1927.)

"Noon hour at Ford Motor Co." (Undated.)

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Detroit's 1927 unemployment problem was so bad that it was spilling over into other cities. When the Chicago Association of Commerce investigated how their city came to be home to 120,000 unemployed men, their report chiefly blamed the Ford shutdown. "Chicago's unemployment would be hardly observable were it not for the great number of out-of-town people brought to the city," the report stated. "Mr. Ford's shutdown ... placed on an already dull labor market at least 100,000 skilled and semi-skilled men, all accustomed to high wages and acceptable working conditions." ("Idleness in Chi not a criterion." The Journal Times, Oct. 20, 1927.) The Detroit Free Press summarized the ripple effect of the shutdown on the nation's economy five months after the layoffs were announced:

Ford's losses have had a direct effect on the rest of the country, particularly on the middle west. To begin with, his shutdown stopped the payrolls in his factories. It is estimated that this lopped more than $1,000,000 a week from Detroit's purchasing power. And that is only a starter. The steel mills of the Cleveland-Mahoning valley district have suffered. Ford was an important customer of theirs. Stoppage of his orders not only cut off a large volume of business; it also reduced the price levels for the remaining customers. It has been a slow summer for the steel men, and Ford is largely responsible. The railroads also felt Ford's withdrawal keenly. The rubber industry was affected, though not so sharply; plate glass manufacturers were hard hit, and the slumping coal industry was pushed down a little bit deeper.

("Ford takes paper loss of $240,000,000 while awaiting new car model." DFP, Oct. 25, 1927.)

A New Headquarters

Five months before the shutdown began, Ford started construction on a new office administrative building on Schaefer Road adjacent to the Rouge Complex, in the City of Fordson, which was later consolidated with the City of Dearborn. A January 1927 announcement stated: "Various of the office departments now located at the Highland Park plant, as well as the present Fordson offices, will be housed in the new building, although this change will in no way affect operations at either plant and space so vacated will be utilized at once for other purposes." ("New office for Fordson." Ford News, Jan. 1, 1927.) That summer, Ford News reported that "the purchasing department will be removed from the Highland Park offices to the new building, as will certain other office departments closely associated with the Fordson manufacturing program." ("New offices ready Jan. 1." Ford News, Aug. 15, 1927.)

The Ford Motor Company Administrative Building, designed by Albert Kahn, was constructed in 1927.

The Ford Motor Company Administrative Building, designed by Albert Kahn, was constructed in 1927.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Finally, beginning in 1928, Ford Motor designated the new building as its official headquarters. The departure from Highland Park was more or less complete on January 25, when a caravan of cars and trucks transported the contents of the Ford archives to their new home at the Schaeffer Road building. The Free Press reported:

There has been a gradual transfer of offices and factory workers from Highland Park to the Fordson plant during the past few months, since the new Model A Ford went into production, but the company has not announced what it proposed to do at Highland Park eventually.

("Ford offices removed from Highland Park." DFP, Jan. 26, 1928.)

With the removal of Ford's headquarters from Highland Park, the city lost one-third of its tax base. Assessors found that taxable property in the city, which totaled $207.8 million at the beginning of the 1927-1928 fiscal year, had fallen by more than $73 million with Ford's departure. ("Tax unchanged despite losses." DFP, Jun. 15, 1928.) Determined to maintain Highland Park's famously low tax rates, the city attempted to balance its budget by cutting expenses. In April 1928, the council eliminated the position of city building inspector, as well as the assistant building inspector and a member of the engineering department. ("Abolish building inspector's post." DFP, Apr. 17, 1928.) A June Free Press editorial noted, "Highland Park has managed to avert a tax rate increase by relieving the payroll of superfluous employes, by refraining from salary increases and by cutting down already over-generous salaries." ("An era of economy in government." Editorial. DFP, Jun. 16, 1928.) Some residents did not even believe that the city could survive such a loss to its tax base, and advocated annexation to Detroit. ("Highland Park citizen urges annexation." Letter to the editor. DFP, Apr. 22, 1928.)

Two June 1928 Detroit Free Press articles show one suburb's loss is another suburb's gain. At left, an article from June 15 reports Highland Park's assessed valuation dropped $73,342,800. At right, an increase of $75,715,365 in Fordson's taxable valuation is reported on June 14.

After the Great Depression hit, Highland Park's taxable valuation fell 10% more. By 1931, the city's bonded debt totaled $1,679,076 for general city bonds, and $3,109,333 for school bonds. Yet the fight to keep taxes low continued. The city cut back on its summer school and night school programs, and instituted a $75 registration fee for the Junior College. City employees earning more than $1,500 per year took a 5% pay cut. The city especially clamped down on welfare recipients. "Applicants who came to Highland Park within the year were told to return to their former homes," the Free Press reported. In that same story, Highland Park Mayor John C. Shields explained, "When the 'unemployed' were first registered for welfare aid, we gave them brooms and shovels and offered them work on the streets and alleys. Only those actually in need stuck to the job. The first week our list of applicants shrunk at least 50 percent." Additionally, many city staff voluntarily donated funds in support of the city's welfare effort. ("Highland Park cuts taxes, limits dole." DFP, Jul. 20, 1931.)

Nearly a Century of Population Loss

The US Census figures for Highland Park give population figures in 1920 and 1930 as 46,499 and 52,959, respectively. But these numbers don't tell the full story, because the city's population actually peaked in between those years. Estimates of Highland Park's mid-1920s peak vary. A 1927 advertisement for Highland Park school bonds puts the population at 60,000; a 1927 Free Press story claimed that the number "exceeds 65,000" ("Highland Park proud of auditors' findings." DFP, Nov. 13, 1927); a 1925 report on municipal water systems estimated 65,255; a 1927 report by the National Board of Fire Underwriters cited 70,000; in 1926 the Free Press claimed 77,000 ("The letter box." DFP, Oct. 11, 1926.); and a 1928 story in that paper guessed a whopping 86,400 ("Detroit close to third city." DFP, Oct. 3, 1928.). Even the lowest of these estimates show a population decrease of at least 11% by 1930.

The population loss was so severe that it was by no means confined to just Highland Park. Even the acting mayor of Royal Oak, in October of 1927, worried that his city "and other North Woodward communities are in danger of losing part of their population," especially in light of inadequade public transportation facilities between Royal Oak and the Rouge complex. ("Buses suggested for Ford workers." DFP, Oct. 11, 1927.)

With a continually declining population, Highland Park's real estate market never had a chance to recover. Back in the 1880s, Captain Stevens and a few other investors established Highland Park as a means of increasing the value of their land holdings and then selling them for profit. But like the Bitcoin and Beanie Baby rackets, the game of ever-increasing real estate values is a Ponzi scheme that collapses sooner or later. By the time Ford left, the game was up in Highland Park. Developers and investors had already moved on to the outer suburbs, keeping the game going through suburban sprawl.

In order to help stabilize the housing market, the US government created the Home Owners' Loan Corporation in 1933 to refinance home mortgages. When the agency created color-coded residential security maps in 1939 to illustrate loan risk levels, all residential sections of Highland Park were shaded yellow or red, designating these areas "definitely declining" or "hazardous," the lowest categories. Quoting directly from government appraisers' area description files, Dr. Craig Wesley Carpenter of Michigan State University has observed:

Government appraisers redlined the neighborhoods in Highland Park with diversity, including where "Italian-Hungarian-Balkan," "Greek," "Jewish," and "Negro & mixture." This redlining occurred after the "removal of Ford Plant from Highland Park left many vacant stores." Although the houses were relatively good quality, "type of population rate the area 4th grade." Government appraisers yellow-graded neighborhoods that did not have Black people living there, though despite relatively quality homes, neighborhoods remained yellow because they had ethnically "mixed social groups."

Detail from a Home Owners' Loan Corporation's 1939 Residential Security Map

(Detroitography)

With the industrial sector, the real estate industry, and even the federal government all betting against Highland Park's future, residents faced many long, difficult years ahead.

The End of an Era

On October 30, 1926, midway between the dedication of the McGregor Library and the production of the last Model T, Highland Park laid the cornerstone for a new city hall on Gerald Street, next door to the old city hall built 15 years prior. The new building, designed by Marcus R. Burrowes and Frank Eurich, Jr., did not require the issuance of bonds. Appropriations from the general city budget were enough to cover the building's $250,000 construction cost. After all, the city could afford it.

Highland Park City Hall in 1927.

Highland Park City Hall in 1927.(Virtual Motor City)

Two months after Ford abruptly terminated all Model T production, the new city hall was ceremoniously dedicated on the evening of July 22, 1927. One can only wonder what feelings prevailed among the people on that day, marking what seems in retrospect to have been a bittersweet occasion.

Two months following the building's completion, the city's first mayor, Royal Milton Ford, died from a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 48. He was born on a farm in Greenfield Township which was annexed to the Village of Highland Park when he was 14 years old. As a young man, he worked for the village clerk for a time before he himself was elected to that position at age 22, occupying that office for 16 years until losing the March 1917 election. He was elected mayor the following year with Henry Ford's personal endorsement. Royal Ford considered himself "retired" after his electoral defeat at age 41. He died at the Highland Park General Hospital on September 7, 1927, and two days later was laid to rest at Woodlawn Cemetery.

(Find a Grave)

To be continued...

Coming soon: Highland Park Part IV: The Davison Freeway

Upon this “rock” let us remake our world!

ReplyDelete