(Archive.org)

(Archive.org)Much of Detroit's easternmost neighborhood, Cornerstone Village, came into the city when a half square mile of territory was annexed from Grosse Pointe Township in 1926. Homebuilding was booming on the east side in the 1920s, whether developers were constructing bungalows for middle-class workers, or designing exclusive enclaves for the rich. The various municipal boundaries coming into shape here, which would influence class divisions even more greatly over time, would sometimes be decided by a surprisingly small number of votes.

The present-day city border formed in part by the Cornerstone annexation begins at the center of Mack Avenue and Cadieux Road, runs east up the center of Mack, then turns northwest at Kingsville Street, ending at Linville Street in the City of Grosse Pointe Woods. This area was one of the last two strips of "unorganized" land (i.e., not being part of a village or city) in Grosse Pointe Township.

Grosse Pointe Township was originally established in 1846, when it was separated from Hamtramck Township. Grosse Pointe Township was itself split in two about fifty years later on May 16, 1895, when the Michigan legislature created Gratiot Township from part of Grosse Pointe. The line dividing the two townships, defined in Act 412 of 1895, was "ten rods" (1,650 feet) north and west of the center line of Mack Avenue. Although Mack runs nearly north-south in this area, the resulting 1,650-foot-wide strip of land lying between Gratiot Township and the the rest of Grosse Pointe Township was sometimes referred to as "North of Mack."

After thirty years of city annexations and village incorporations, the political boundaries of Gratiot and Grosse Pionte townships were arranged like this:

The east side building boom did arrive until after 1923, when the city reconstructed Conner's Creek as an immense, 54-foot-wide sewer—believed to be the largest in the world at the time. Homes began popping up all over the areas annexed in 1917 and 1925, now having access to newly extended city services, including sewers, transit, and fire protection. But some property owners were building houses in subdivisions in unincorporated portions of Grosse Pointe Township where these facilities were completely unavailable. The situation is described in April 1924 edition of the Grosse Pointe Civic News:

In the past five years there has been considerable building in the "North of Mack" section. No other section of our Township has witnessed the construction of more homes. The area lacks improvements. Most of the homes are on streets unpaved and without sidewalks, sewers, or water. In some cases the people carry water in buckets the distance of a quarter of a mile.

Naturally, the residents have been anxious to remedy the conditions, and have looked to the organized villages of Grosse Pointe for annexation.

The past failure of any accomplishment along this line has been due to a lack of unified effort on the part of the people north of Mack and also to the indifference of the organized areas....

Grosse Pointe cannot afford to neglect the annexation or organization and subsequently the development of any part of the township adjacent to the City (of Detroit), unless it is expected that at some future time Detroit will annex the area in question.

It may be that the best solution to the problem is future annexation by Detroit.

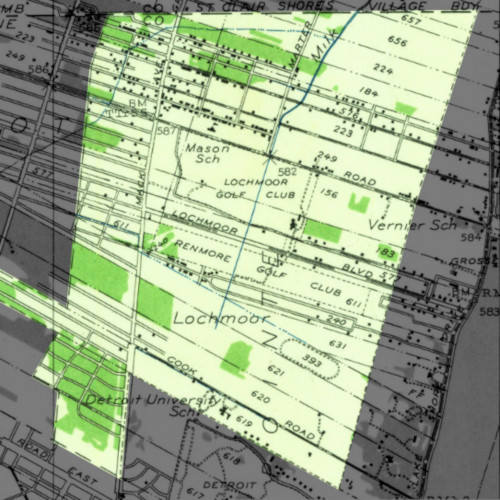

The "North of Mack" strip is highlighted on the map below, which is taken from a 1925 real estate atlas of Wayne County. The yellow-shaded areas indicate subdivided tracts, where people were reportedly building houses before running water was available.

(Historic Map Works)

(Historic Map Works)Fortunately, as those words in the Civic News were being written, another government improvement project had just been announced, potentially increasing the value of the "North of Mack" section and thereby spurring annexation petitions. In April 1924, the Detroit Rapid Transit Commission—collaborating with the road commissioners of Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb counties—announced a metropolitan transportation plan, which called for rebuilding specified roads throughout the region as 204-foot-wide "superhighways," in order to accommodate the explosive growth of both automobile ownership and suburban developments in just a few years. Seven Mile Road and Mack Avenue, highlighted on the map from the commission's report below, were recommended for expansion as part of the new highway network.

Detail from Super-Highways and Major Thoroughfares for Detroit and Environs.

Detail from Super-Highways and Major Thoroughfares for Detroit and Environs.The annexation area lies southwest of the intersection.

(Hathi Trust)

"Seven Mile Superhighway at Mount Clemens Drive (Harper Avenue)," circa 1930.

"Seven Mile Superhighway at Mount Clemens Drive (Harper Avenue)," circa 1930.(Hathi Trust)

These superhighways were originally intended to facilitate not just automobiles, but also streetcars and rapid transit. The Detroit Rapid Transit Commission's report called for reserving 204-foot-wide corridors for future superhighways, which is why Seven Mile Road (now called Moross Road) was built to this grand width between Kelly Road and Mack Avenue. Suburban real estate dealers with property anywhere near a these proposed superhighways freely advertised the benefits of living near rapid transit almost as if the tracks had already been laid. Below is a detail from a 1924 advertisement for a west side subdivision at Seven Mile and Greenfield, where the road was never even widened to the superhighway width.

(freep.newspapers.com)

(freep.newspapers.com)Wormer & Moore's "Mack-Seven Mile Subdivision"

These roadway improvements would not have escaped the attention of Wormer & Moore, a Detroit real estate firm founded by Clarkson C. Wormer Jr. and Lucian S. Moore Jr. in 1919. The firm originally dealt with downtown real estate and exclusive residential areas such as Indian Village and Grosse Pointe. They met with enough success by 1923 to construct an eight-story downtown office building, now known as the Iodent Building.

Wormer & Moore Building, 2231 Park Avenue, Detroit.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Around the time it occupied its new headquarters, the firm created a department to deal exclusively in suburban subdivision lots, as the entire region got swept up in a speculative land craze that would ultimately end with the Great Depression. Any corn field could be surveyed into a subdivision, but Wormer & Moore specialized in lots which were close to paved roads and included pre-installed improvements (sewers, sidewalks, etc.) in the purchase price. "All conditions are favorable to vast operations in the subdivision field, wherever good roads and street car service are available," William L. Helmer, head of the department, said in a press release. ("City best realty center in America." Detroit Free Press, Jan. 11, 1925.) The department's fifty salesmen made a record $3.75 million in sales in 1924.

In June 1925, Wormer & Moore began advertising their new Mack-Seven Mile subdivision, located southwest of the intersection. The firm was already doing a brisk business with several nearby subdivisions put on sale earlier that spring, including Merriweather Park, Roland Estate, Seven-Mile Cadieux, and Seven-Mile Cadieux No. 1.

The "Outer Drive" referred to in this ad is today's Chandler Park Drive.

Detroit Free Press, June 14, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)

Wormer & Moore announced that Mack-Seven Mile lots would be put on the market June 28, 1925. The advantages of the location included service by Detroit's new bus system, which was extended up Mack Avenue up to Seven Mile Road; Seven Mile Road's distinction of being the longest paved road in Wayne County, at 30 miles; its proximity to the new Mount Clemens Drive, which is now Harper Avenue; and various "restrictions" placed on the property. Prices started at $1,350 per lot, and the first week's sales netted $200,000.

Detroit Free Press, June 21, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, June 21, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)According to a Detroit Free Press article—which appears to quote heavily from a company press release—"restrictions" in another nearby Wormer & Moore subdivision "confined the development to a residential section of the better class." The article quoted Helmer, the company's sales manager, saying, "A tremendous factor in the almost unbelievable increases in property value, however, has been the building restrictions. There are few highly-restricted developments of this character in the city of Detroit except on the east side..." ("Mack-7 Mile Road activity cited." Sep. 13, 1925.) The usual types of rectrictions at the time included building setbacks, type of building (e.g., single-family homes only), minimum cost, type of construction (e.g., exclusively brick), and racial occupancy. Deed restrictions prohibiting any person other than a member of the Caucasian race from living on a particular lot were very common at the time and enforced by the government.

The Vote

Detroit Free Press, August 29, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)

In August 1925, the Wayne County clerk announced that the proposal to annex territory from Grosse Pointe Township to Detroit would be on the ballot at the upcoming election of October 6. The announcement was made after the county board of supervisors received petitions calling for the change in boundaries. Under the Home Rule City Act, the petitions had to be signed by registered voters in the affected area, equalling at least 1% of its population. Unlike the case of the 1917 annexation, the circumstances surrounding this petition drive didn't receive media attention. However, such campaigns were usually orchestrated by Detroit's well-organized real estate interests. There is no evidence that Wormer & Moore were involved in the annexation, but the circumstances surrounding their development can be observed in many other annexations to the city.

The only item on the ballot for Grosse Pointe Township voters was the annexation question. But Detroiters were also voting on a city council race, road widening expenditures, proposals to annex land from Redford and Greenfield townships (which will be covered in another post), and not just the one annexation proposal from Grosse Pointe Township, but two. The two Grosse Pointe Township parcels covered the entire "North of Mack" strip, from Cadieux Road all the way up to Macomb County. The line dividing the strip into the two separate annexation proposals was the border between two old French ribbon farms, designated as Private Claim 123 and Private Claim 617 after US occupation.

Somewhere, in an alternate universe where the second proposal passed, Detroit's northeastern border might look like this:

Of course, the rest of Gratiot Township would probably also be annexed in this universe...

Of course, the rest of Gratiot Township would probably also be annexed in this universe...Following the annexation announcements, Wormer & Moore began running ads for their Mack-Seven Mile Road subdivision which included a drawing of a bustling street corner in some great metropolis, and the promise of a rapid rise in value for an easy profit.

Detroit Free Press, September 13, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, September 13, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)The One That Passed

The first annexation proposal won at the election of October 6, 1925. It was approved by voters in Detroit (74,194 to 34,204), in the annexation area (76 to 57), and in the remainder of Grosse Pointe Township (126 to 56). The law required majorities in all three areas for the proposal to carry. The second proposal passed in Detroit and Grosse Pointe Township, but not in the annexation area. (More on that in a moment.)

Annexation proceedings were filed with the Secretary of State on January 15, 1926, legally completing the process. The addition brought about 1,000 residents into Detroit, and added $1.2 million onto the city's tax rolls. Grosse Pointe Township was also relieved of $170,000 of school bonds, which were added to Detroit's debt, but the city also gained the township's Hanstein School, built in 1918 and added onto in 1923. Once located at 4290 Marseilles, it was demolished in 2015 for a sports dome.

The Hanstein School in 2013. (Google Street View).

The Hanstein School in 2013. (Google Street View).In what looks like another Wormer & Moore press release rewritten as a Detroit Free Press article, sales manager Helmer declared that the intersection of Mack Avenue and Seven Mile Road was "unquestionably ... destined to be one of the fastest developing business intersections on the east side," now that the area was within the city limits. "Bus lines on Mack avenue, affording the best of transportation facilities, have done much to enhance the desirability of the carefully restricted Mack-Seven-Mile road subdivision." Helmer reminded Free Pressreaders that Wormer & Moore's east side subdivisions have "yielded consistent profits, especially in those sections where rigid restrictions have attracted builders of substantial homes." ("Mack-7 Mile area gaining." Detroit Free Press, Oct. 25, 1925.) The city made the land valuable, and the developers enjoyed the profits.

(freep.newspaper.com)

(freep.newspaper.com)Due to the extreme overabundance of subdivision plats laid out throughout metropolitan Detroit during this time, many developments had only just constructed a few model homes by the time the stock market crashed in 1929, and the torrent of building activity was reduced to a trickle. An indication of how long it took to develop the Mack-Seven Mile Road subdivision (and many others like it) can be seen on Hillcrest Street just a few doors up from the city border, where a house built in 1928 under the supervision of Wormer & Moore stands next to a "colonial" constructed in 1966:

Hillcrest Street, Mack-Seven Mile Road subdivision, Detroit.

Hillcrest Street, Mack-Seven Mile Road subdivision, Detroit.(Google Street View)

The eastern and northern edges of this annexation contribute to just more than two miles of today's city border.

The One that Got Away

Unsuccessful annexation from Grosse Pointe Twp. to Detroit, 1925.

Unsuccessful annexation from Grosse Pointe Twp. to Detroit, 1925.Back on the election of October 6, 1925, the second annexation proposal failed, despite carrying by two-to-one both in Detroit (72,383 to 34,027) and in the outside part of Grosse Pointe Township (205 to 106). But within the annexation area itself, there were only ten registered voters. Nine of them voted against the measure. The tenth ballot was reportedly spoiled and could not be counted. What exactly happened?

Following the election, the Grosse Pointe Civic News—published by the Citizens Association of Grosse Pointe Township—reported on a general lack of interest in the election, citing a turnout of less than 10%. It also noted:

It is rumored that township officers were active in opposing the annexation of this portion of the township and campaigned at the polls against annexation. It would seem that any campaign conducted by an official either for or against a public question is outside his regular line of duty and should be discouraged.

It is also rumored that township territory outside of the present Grosse Pointe Villages is planning to incorporate as the village of Lochmoor. What progress has been made other than the selection of a name is not known. It is evident that this territory needs public improvements not obtainable except by annexation or incorporating as a separate village.

("Special election results." Grosse Pointe Civic News, October 1925.)

The Village of Lochmoor

Detail from a 1936 real estate atlas of Wayne County. (Historic Map Works)

The Lochmoor Village project had actually been in the works for nearly a decade by the time that "rumor" was printed. Its origins can be traced back to the Grosse Pointe Township Improvement Company, which was incorporated in December 1916 in order to establish a private golf course attached to an exclusive neighborhood in the township. The Lochmoor Club was organized in February 1917 with 68 founding members, including at least two officers of the land company, as well as Clarkson C. Wormer Jr. of Wormer & Moore. The Grosse Pointe Township Improvement Company recorded the "Lochmoor Subdivision" plat at the county registrar in July 1917. The plat included a 128-acre outlot set aside for a golf course, which the Lochmoor Club purchased from the land company in March 1919. The company retained ownership of the lots, which were "sold on such conditions as to insure residential development beneficial to the club interests." ("Detroit adds country club." Detroit Free Press, Mar. 11, 1917.)

Detail from the Grosse Pointe Township Improvement Company's plat of the Lochmoor Subdivision.

(State of Michigan)

Daniel Fickes Altland, who was both the executive director of the Lochmoor Club and president of the Grosse Pointe Township Improvement Company, envisioned a community of elegant homes lining a 100-foot wide boulevard running the length of the subdivision, from Jefferson Avenue to Mack Avenue. Altland wished to hire the Olmsted Brothers, the firm founded by the sons of Frederick Law Olmsted, as the project's landscape architects. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., who happened to be in Ann Arbor at the time, visited the property in March 1917. Olmsted thought the site had great potential, but he thought the subdivision plan was subpar. He wrote to Altland:

To construct the boulevard as proposed, with an absolutely uniform design throughout ... without deviation from mathematical straightness of alignment, and without other relief from their thin and ribbon-like extention, would tend to produce a commonplace and skimpy looking result. It would almost inevitably look like an attempt to do a grand kind of thing in a small, timid, penurious manner; and no amount of ingenuity of expense lavished upon planting or other subsequent decoration could successfully overcome this basic mistake. (Source.)

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.Olmsted and a Detroit-based architecture firm worked with the Lochmoor group for a few weeks, but Olmsted felt his advice was being ignored and ultimately withdrew from the project. He wrote to Altland, "Since we cannot convince ourselves that the plan you have adopted has a sound business basis to justify its artistic defects we have no choice but to withdraw from responsibility in the matter."

They ignored his advice and built the boulevard exactly as planned. (Google Street View)

They ignored his advice and built the boulevard exactly as planned. (Google Street View)In July 1926, nine months after the northern annexation proposal was defeated, Wayne County received petitions from voters in the remaining unorganized portion of Grosse Pointe Township to incorporate as the Village of Lochmoor. The proposal won by vote of 116 to 25 on the election of September 16, 1926. A commission was elected to draw up a charter, which was approved by voters on January 4, 1927 by 182 to 22. The incorporation became official on that day.

Five candidates, running unopposed, were elected to write the village charter in September 1926: Joseph E. Beaufait, James Carter, James Goodrich, Edward Vanderbush, and Edmund C. Vernier. At the January 1927 election, voters also selected the village's first officers. Edmund C. Vernier, running unopposed, was elected the village's first president.

(freep.newspapers.com)

Vernier's signature of approval on a property plat of Grosse Pointe Township, circa 1915.

Vernier's signature of approval on a property plat of Grosse Pointe Township, circa 1915.(University of Michigan)

Vernier was born in Grosse Pointe Township in 1867 to the pioneering family for whom Vernier Road is named. He operated the popular Vernier Villa, a roadhouse tavern on Jefferson Avenue whose specialties included frog legs. Vernier was first elected supervisor of Grosse Pointe Township in 1902, but he was removed by the governor in March 1919 for falsifying documents in order to lower township property tax assessments by $3,000,000. The people immediately voted him back into office anyway. In fact, he served as township supervisor (and sometimes as treasurer) almost continuously from 1902 until his death in 1934, usually running unopposed. Vernier also served on the Wayne County Board of Supervisors.

Edmund C. Vernier stands second from left in this photo.

Detroit Free Press, April 13, 1932. (freep.newspapers.com)

When Grosse Pointe Township was assessed for the cost of paving Eight Mile Road, Vernier refused to spread the assessment on his tax rolls or disburse the funds to Wayne County in 1928 and 1929. The county covered the townships's $65,000 share, but then would not release funds to the local school district in Grosse Pointe, which was then forced to borrow funds to cover teacher payroll. The state government finally caved in to Vernier in 1932, when a special session of the legislature was convened to amend the road tax law. Following this victory, Governor Wilbur Brucker was the guest of honor at a celebratory dinner at the Grosse Pointe Yacht Club, where Vernier was the toastmaster. ("Supervisors fete Brucker." Detroit Free Press, Jul. 7, 1932.)

(Grosse Pointe Public Library)

(Grosse Pointe Public Library)A proposal to annex 44.13 acres from Gratiot Township to Lochmoor was presented to voters at the election of November 16, 1931. The area to be taken in was divided into three parcels. One parcel was a single tract of property, but the other two were part of subdivisions which were mostly already within the village limits of Lochmoor. The subdivisions—Grosse Pointe Country Club Woods and Grosse Pointe Country Club Woods No. 1—were marketed by Wormer & Moore, who advertised "rigidly restricted residence sites." They were literally named for the woods behind the Country Club of Detroit (not to be confused with the Lochmoor Club), which was "one of the few remaining areas in Detroit that is covered with native timber." ("Wooded land in big demand." Detroit Free Press, Feb. 28, 1926.)

Detroit Free Press, March 7, 1926. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, March 7, 1926. (freep.newspapers.com)Vernier, who was serving as both township supervisor and village president at the time, urged voters to approve the annexation. He pointed out that sewers had already been installed, and that the village would not be absorbing any bonded indebtedness. Village voters approved the annexation by 103 to 71. In Gratiot Township, outside of the annexation area, the vote was 23 to 0 in favor. No votes were cast within the annexation area, which was vacant as late as 1950. The boundary change became legal on November 24, 1931, upon the filing of the annexation proceedings with the Michigan Secretary of State.

In August 1938, Lochmoor Village President Jules De Porre announced that "a proposal has been made to the village officials of the Village of Lochmoor to change the name of the village to Grosse Pointe Heights." ("Lochmoor Village may change name." The Grosse Pointe Review, Aug. 4, 1938.) By November, the new name proposal had switched to "Grosse Pointe Woods." Voters approved the amendment to the village charter changing the name on March 13, 1939 by 479 to 205. A local paper proclaimed that the updated name "will undoubtedly give new inspiration for an enlivened ambition to strengthen the encouragement of the building industry which has been carried on during the past year to a most surprisingly and unexpected extent." ("Laud village officers of Grosse Pointe Woods." The Grosse Pointe Review, Apr. 6, 1939.) The village later incorporated as the City of Grosse Pointe Woods on December 11, 1950.

Lochmoor on a 1936 topographic map. Most construction activity was confined to the northern part of the village, as indicated by the small black squares representing buildings.

(USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer)

We may never learn the identities of the township officials who allegedly stopped the second Grosse Pointe Township annexation proposal from passing in October 1925, thereby determining the boundaries of today's east side communities. But if a certain representative of the old township office holders could bend the governor of Michigan to his will, one imagines that it would be comparatively easy for him to persuade nine voters to see his side of things.

Scenes from the Border

17133 Mack Avenue was built in 1916, according to tax records. Five houses, which once stood behind it, were removed in 1929 to accommodate the widening of Mack.

17133 Mack Avenue was built in 1916, according to tax records. Five houses, which once stood behind it, were removed in 1929 to accommodate the widening of Mack. Allemon's Landscape Center, Detroit.

Allemon's Landscape Center, Detroit. Detroit businesses on Mack near Woodhall Street.

Detroit businesses on Mack near Woodhall Street. Detroit businesses on Mack near Canyon Street.

Detroit businesses on Mack near Canyon Street. Harvey Animal Hospital comes highly recommended!

Harvey Animal Hospital comes highly recommended! Village Locksmith, Grosse Pointe Farms.

Village Locksmith, Grosse Pointe Farms. Looking west on Warren Ave. from Mack.

Looking west on Warren Ave. from Mack. When I was your age this was a Chinese restaurant with a tiki bar.

When I was your age this was a Chinese restaurant with a tiki bar.

The above photo was taken facing north up Lannoo Street in the Mack-Seven Mile Road subdivision. According to the Detroit Historical Society, Lannoo Street was named for Belgian immigrant Emeric Lannoo, the farmer whose land comprised part of this and several other nearby subdivisions.

The things people believe! Oh well, if they think they're in Grosse Pointe Farms, that's none of my business...

The things people believe! Oh well, if they think they're in Grosse Pointe Farms, that's none of my business... Cleopatra Mediterranean Grill, Detroit.

Cleopatra Mediterranean Grill, Detroit. I'm not knocking the old Kinko's at Mack and Moross, but I think Wormer & Moore's illustration was a little over the top.

I'm not knocking the old Kinko's at Mack and Moross, but I think Wormer & Moore's illustration was a little over the top. Pointe Plaza, Detroit. (Formerly Grosse Pointe Township.)

Pointe Plaza, Detroit. (Formerly Grosse Pointe Township.)The easternmost corner of the City of Detroit lies where the center of Mack Avenue meets the line between Private Claims 123 and 617. That corner is marked on the image below, using the current center line of Mack. However, if you want to go by the old center line of Mack, before the avenue was widened during the 1920s east side building boom, then the corner should be about six feet into the first lane on the other side of the grassy median.

Part of Saint John Hospital crosses the city border.

Part of Saint John Hospital crosses the city border.The next photo was taken on the same line as the photo above, but farther away and looking in the opposite direction (note the hospital again). This is Kingsville Street, which was platted to lie exactly on the city border. But for one and a half blocks, Kingsville is only half a street, with hardly enough room for two cars to pass. The lucky Grosse Pointe Woods household on the left gets to use part of this half of a street as a driveway.

The brick wall was built in the 1970s by Saint John Hospital to replace a fence at the insistence of nearby Grosse Pointe Woods residents. Some neighbors tried to convert Raymond Street into a dead-end at Kingsville in 1984, but public safety officials pointed out that doing so would reduce the frequency of police patrols and complicate fire safety and trash collection, so the intersection was left open.

This street was originally called Kingsbury when real estate developers began drawing up subdivision plats around here in the 1920s. The name of the street was changed to Kingsville by Detroit on May 14, 1940.

Facing northwest. The parking garage is part of the Saint John Hospital complex.

Facing northwest. The parking garage is part of the Saint John Hospital complex.In the photo below, the Cornerstone annexation Line ends just beyond where the brick wall on the left stops. From that point on, Detroit borders Harper Woods all the way up to Eight Mile Road—which will be the subject of the next post in this series!

* * * * *

To check out these borders in greater detail, click here to download Borders3.kmz. Open the file in Google Earth, and select which items you want to show or hide from the map.

Great article! I enjoyed the photos of the current streets. Very nice.

ReplyDeleteone minor typo: Kingsville forms the border of Detroit and Harper Woods up to Kelly Road - not Eight Mile

ReplyDeleteTrue

DeleteTo clarify, I meant that from "that point on" (after where the brick wall ended in that photo), Detroit borders Harper Woods, all the way up to Eight Mile. I should probably reword that to make that more clear. Thanks!

DeleteSo, we get to learn about why the back of the lots onf Kingsville form the border with Harper Woods instead of Moross, next? I've always been curious about that.

ReplyDeleteI'm actually glad 7 Mile wasn't turned into a "superhighway" to be honest. lol When you think about how 8 Mile ultimately developed - completely without human scale, useless tree lawns or barrels of parking in front yards, etc. - I shiver to think of that x 2.

BTW, I assume Lochmoor wanted the northern strip to control each side of Mack? Because otherwise, I can't think of why the southern strip wanted in and the northern strip didn't, if it was about getting better municipal services. You'd kind of think Gratiot Township would have been more against that particular annexation than Grosse Point, since it would have enveloped what remained of Gratiot on three sides.

Delete