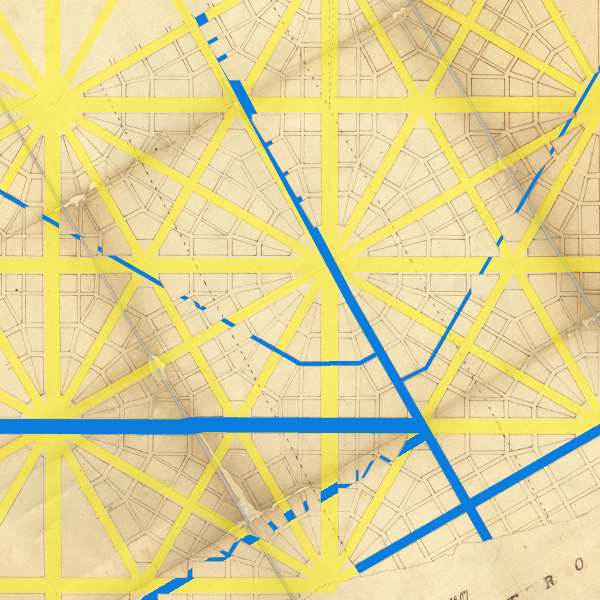

The arrangement of Detroit's main avenues, radiating from the center of the city like the spokes of a wheel, is often attributed to Augustus Woodward's Plan of Detroit, devised between 1805-1807. This is not completely accurate. When you compare today's radial avenues to early renditions of the Woodward Plan, it's clear that the two are not completely in sync.

In fact, the Woodward Plan did not call for five avenues to extend from a central area, but for dozens of avenues to crisscross a busy city.

While some segments of these roads did begin on the Woodward Plan, Detroit's characteristic radial avenues are mostly the result of a military highway system implemented by Governors William Hull and Lewis Cass in the 1810s and 1820s. Today's roads don't so much extend outward from the Woodward Plan as much as they were skillfully woven into it after the city was already surveyed.

This is the first in a series of articles about the early origins of Detroit's radial avenues--when they were laid out, why they exist where they do, and what connections they might have to the Woodward Plan or Native American trails.

Detroit's Main Street

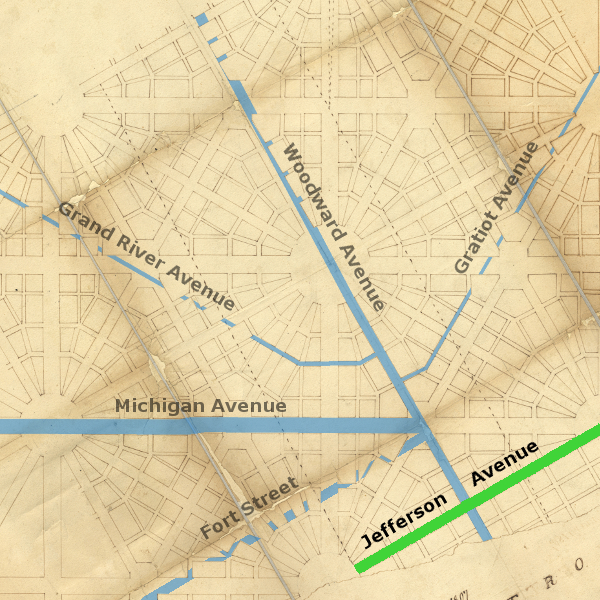

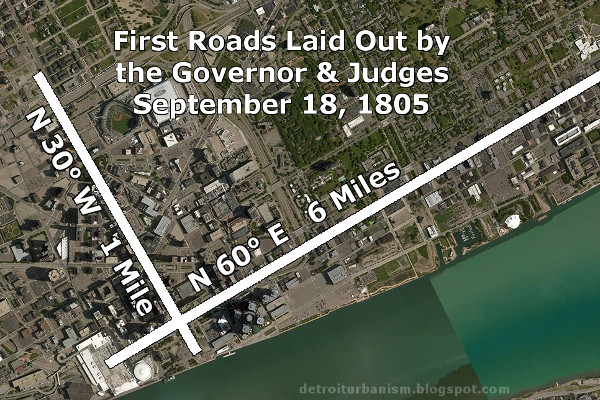

The first pieces of the radial system to be laid out (if only on paper) were one mile of Woodward Avenue and six miles of Jefferson Avenue. There were in fact the very first roads established after the great fire of June 11, 1805. Although the Woodward Plan had not yet been officially enacted, these roads were created by law in section two of "An act concerning highways and roads," passed by the territorial government on September 18, 1805. Neither road immediately had a formal name, but early documents refer to Jefferson Avenue as "Main Street."

Jefferson Avenue was never built six miles straight as defined in the 1805 law. On June 23, 1817, the territorial government passed An Act for Opening and Regulating Roads and Highways, which repealed the original legislation and redefined Jefferson Avenue as extending only one mile east of Woodward Avenue, and west from Woodward until it intersected the river. Six months later, a second act entitled "An Act for Opening and Regulating Roads and Highways" was passed on December 1, 1817, which repealed the June act but did not re-establish Jefferson Avenue. This law was in turn repealed on December 30, 1819 with "An Act to Regulate Highways," which once more defined Jefferson Avenue as extending from the river to one mile east of Woodward Avenue.

On April 26, 1821, the territorial government approved "An act to extend Jefferson-avenue in the city of Detroit," which continued the avenue eastward "until it shall intersect the ancient French road, now traveled from La Grosse Pointe to the city of Detroit." This straight, "radial" portion of Jefferson Avenue remains just under three miles long, from Cobo Hall to just beyond the Douglas MacArthur Bridge at Belle Isle.

It was some time until Jefferson Avenue was built that far. Thomas Palmer recalled that, during his childhood in the 1830s, "Jefferson avenue was the principal street for business and residences. A rail fence terminated it at Russell street, and nothing but farms existed beyond."

Grave Obstruction

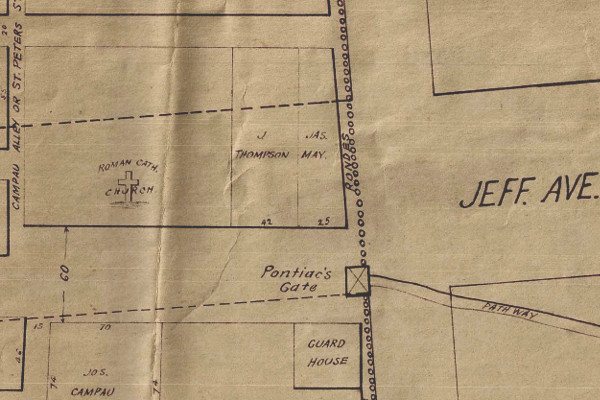

To open Jefferson Avenue, the government needed to obtain private property both from the surrounding farms as well as the old town of Detroit. Although the great fire of 1805 had removed every building (except one) from the road's path, there was a particularly problematic obstacle remaining: the Roman Catholic cemetery. St. Anne's Church burned in the fire, but its burial ground remained intact partially on land that was to become part of the avenue, between what is now Griswold and Shelby Streets.

Detail from Detroit - Prior to the Fire of June 11, 1805, by R. J. Mackey.

Image courtesy Detroit Historical Society. (Source.)

After a lengthy dispute between government and church officials, the graves were ultimately moved. In 1889, historian Silas Farmer wrote,

There are living witnesses who, as late as 1818, saw graves occupying a portion of what is now Jefferson Avenue ; from time to time since then, as excavations have been made for sewers and cellars in the vicinity, remains have been uncovered.

East Jefferson Avenue

From a point just beyond the bridge to Belle Isle, East Jefferson Avenue joins "the ancient French road" to Grosse Pointe. This original road veered inland away from the river in order to avoid what was once Le Grande Marais (The Great Marsh). The site of the marsh, now dry land, was located close to the present-day border of Detroit and Grosse Pointe Park.

The path of East Jefferson Ave. avoids what was once marshland.

Detail from an 1876 atlas of Wayne County. (Source.)

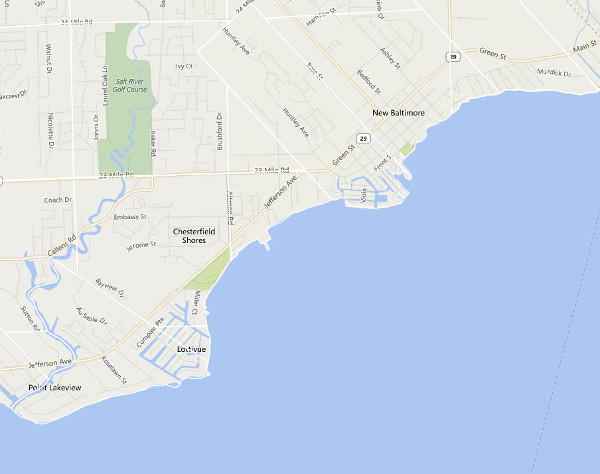

The remainder of East Jefferson Avenue in Metro Detroit more or less follows the ancient footpath that paralleled the shore of Lake St. Clair. Orange Risdon's 1825 map of southeast Michigan shows an Indian trail along the lake shore in what is now Chesterfield Township and the City of New Baltimore. In the detail from the Risdon map below, the area marked by three triangles and the initials "I.R." was a Chippewa reservation between 1807-1836.

Detail from Orange Risdon's 1825 map of the Michigan Territory. (Source.)

East Jefferson Avenue in Chesterfield and New Baltimore today.

Hull's Trace

On the west side of the city was another "ancient French road" that had started as a Native American trail. What was a humble dirt road following the Detroit River to Lake Erie when the Americans Arrived would be transformed into a military highway.

On December 19, 1808, the territorial government passed "An act for laying out and opening a road from the city of Detroit to the foot of the rapids of the Miami, which enters into Lake Erie." This badly needed military supply road was to connect Detroit to what was soon to be the site of Fort Meigs, or what is now Perrysburg, Ohio.

Governor William Hull ordered a route for the new road to be surveyed immediately. An 1809 petition to President James Monroe (suspected to have been written by Augustus Woodward) alleged that Hull "authorised a number of Commissioners to explore a road to the Miami [River], in the dead of winter; when the country was but one sheet of ice and snow; and which it would be impossible for the same, or any other persons to find again in the summer time." The criticism would prove to be valid.

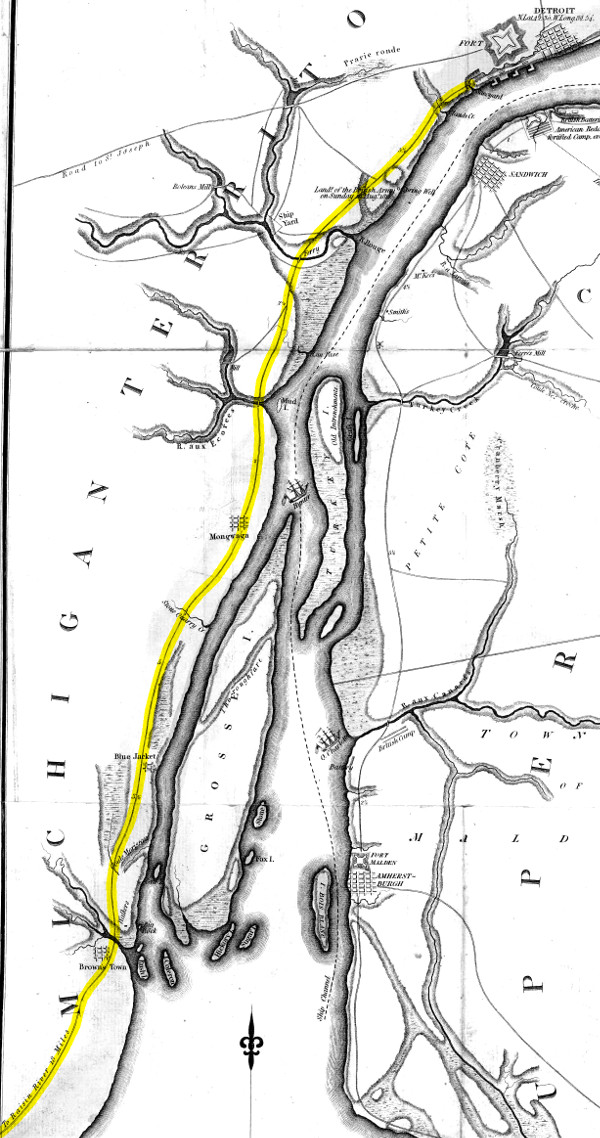

A British map of the Detroit River published in 1813 with Hull's Road highlighted.

Note that the road travels through the Indian villages of Maguaga and Brownstown.

Image courtesy DavidRumsey.com (Source.)

Construction on the road was delayed until the very eve of the War of 1812. Captain Hubert Lacroix began the work in Monroe, sending part of his force of 150 militiamen north to cut the road toward Detroit, with the remainder working southward. Meanwhile, Governor Hull and a force of 2,300 soldiers quickly hacked their way northward from Ohio. In June of 1812, Lacroix complained, "I have not been able to find the road exactly in the place laid out by the Commissioners, but according to the best information that I have been able to obtain, we are nearly in the same course." According to researcher Daniel Harrison, the road was built over the easy-to-find shoreline Native American trail, rather than the much safer inland route surveyed three years before. Constructing the road in this vulnerable location deprived Fort Detroit of a reliable supply line, which was a major factor in its surrender to the British in August 1812. The Battles of Brownstown and Maguaga were fought on this road days before Detriot's surrender.

Historical marker in River View Park, Brownstown Township.

Photograph by the author.

Macomb's Military Highway

In May of 1816, the U.S. Secretary of War ordered Major General Alexander Macomb, an experienced engineer, to build a road between Detroit and Fort Meigs. Rather than start from scratch, Macomb essentially widened and reinforced Hull's road. He started in Detroit, reaching Monroe in November of 1816. Two years later, he reported that the road had been completed to within eight miles of Fort Meigs. "The road is truly a magnificent one," he wrote, "being eighty feet wide cleared of all the logs and under brush, every low place causewayed and all the creeks and rivers requiring it bridged in a substantial manner."

Joseph Fletcher's 1818 survey of what is now the townships of Brownstown and Berlin shows this road where it crosses the Huron River. Today's Jefferson Avenue very closely follows the 200 year old route, with a few alterations.

"A durable road which should remain for ages"

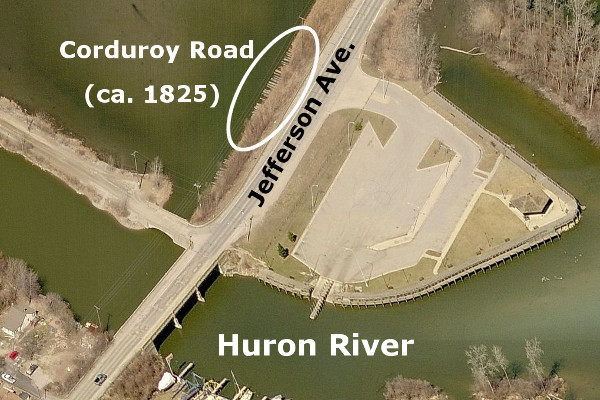

Lake levels were unusually low in 1812. As they rose, the original crossing at the Huron River in Brownstown Township became submerged. This required the relocation of part of the road west of the original path.

Left: Aerial image of the Jefferson Ave./Huron River crossing today.

Right: Fletcher's 1818 survey showing the original route.

Gabriel Godfroy owned a ribbon farm on the north side of this bend in the Huron River. His tenant, Claude Campau, farmed the land and operated a ferry on this site where the original Native American trail crossed the river. Hull's troops hastily built a bridge on this spot in 1812, which Godfroy replaced with a toll bridge five years later.

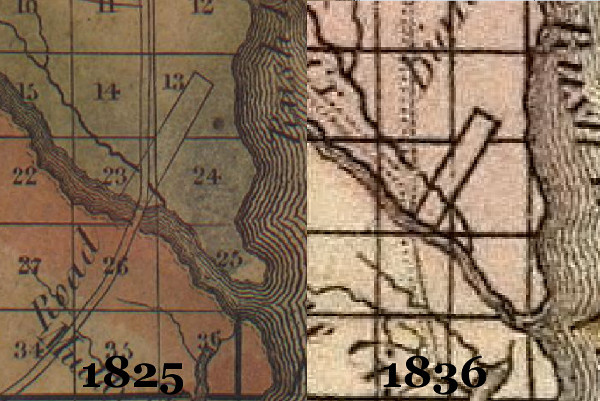

Old maps show the road was rerouted between the 1820s and 1830s. The slanted rectangle in the images below is Godfroy's ribbon farm. Orange Risdon's 1825 map shows the road passing through the base of the farm at Godfroy's toll bridge. But in John Farmer's 1836 map, the road already bypasses this spot.

The road built by Macomb evidently did not satisfactorily hold up to the low, wet conditions of the land south of Detroit. In 1824, Congress appropriated $20,000 for the survey and construction of a road from the Ohio border to Detroit. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun appointed Lewis Cass superintendent the project. While surveying the route, Cass realized that the funds would be insufficient to construct a durable road at its full length of sixty miles. Instead, he chose to lay out a higher quality road where conditions were the most difficult. He wrote,

A permanent road should be made over the worst part of the country... We should possess a durable road, crossing an almost impassable swamp, which, with occasional repairs, would remain for ages. I did not hesitate to make such arrangements, as would give a character of permanence to the work.Cass designated Otter Creek (four miles south of present-day Monroe) the southern terminus of the project. Private contractors bid for quarter mile portions of the road, and work was well underway by 1825. Congress appropriated $12,000 to continue the road south of Monroe in 1827.

Click here to view a survey of the improved 1825 route, which in some sections indicates where the new survey departed from the previous military road.

Like Macomb and Hull before him, Cass mostly followed the Native American shoreline trail. The segment that approaches the Huron River was an exception, having been rerouted slightly inland.

The original and new crossings at the Huron River in Brownstown.

Cass's road, like the original, was a "corduroy road," so called because its base consisted of logs laid across its path. Amazingly, many of these logs were found to be intact beneath Jefferson Avenue (or, more accurately, just alongside it), exposed by low water levels in 2000.

Since 2000, the Huron River has returned to higher levels. Still, parts of the road's foundation--logs felled two centuries ago--remain visible below the surface of the water. More than 500 logs spanning one quarter of a mile have, as Cass intended, survived for ages. Who knows how many miles of centuries-old corduroy roads might remain buried beneath the streets of Metro Detroit?

Remaining fragments of the 1825 corduroy road, now West Jefferson Avenue.

Photograph by the author.

Photograph by the author.

Photograph by the author.

Photograph by the author.

See photos of what the surviving remnants of the corduroy road looked like when water levels were lower here and here.

Check back soon for Radial Avenues Part II: Woodward Avenue!

Nice Work

ReplyDeleteWow, excellent work again, especially with those photos of the old corduroy! I've been wanting to go take a look at that spot myself.

ReplyDeleteTop notch work, as usual. So let me see if I have got this right. If I understand your information correctly, the logs remaining underneath Jefferson Avenue at the Huron River crossing are from 1825, not 1812. Doesn't that make the historical signage at the site wrong? It also means that all the newspaper articles that appeared in 2000, as well as Mr. Harrison’s dissertation on the subject, are all incorrect in calling these logs remnants of Hull’s Trace. They are instead remains from Lewis Cass’s 1825 rerouting of the Huron River crossing. That is not quite as “sexy” as being a part of the original Trace, but certainly worth noting. A true historian follows the evidence wherever it leads, rather than selecting the most interesting interpretation. Thanks for doing your homework!

ReplyDeleteI'm Абрам Александр a businessman who was able to revive his dying lumbering business through the help of a God sent lender known as Benjamin Lee the Loan Consultant of Le_Meridian Funding Service. Am resident at Yekaterinburg Екатеринбург. Well are you trying to start a business, settle your debt, expand your existing one, need money to purchase supplies. Have you been having problem trying to secure a Good Credit Facility, I want you to know that Le_Meridian Funding Service. Is the right place for you to resolve all your financial problem because am a living testimony and i can't just keep this to myself when others are looking for a way to be financially lifted.. I want you all to contact this God sent lender using the details as stated in other to be a partaker of this great opportunity Email: lfdsloans@lemeridianfds.com OR WhatsApp/Text +1-989-394-3740.

ReplyDelete