Detroit's current borders superimposed over an 1876 map of Wayne County.

Detroit's current borders superimposed over an 1876 map of Wayne County.Researching exactly where Detroit's sometimes confusing borders lie—and how they got that way—has been a long-overdue topic for this long-neglected blog. This post will be the first installment of an in-depth series on the history of the borders of the city. We will begin following the municipal boundaries starting where the eastern border meets the Detroit River, and then progressing counterclockwise from there.

I had in fact mostly finished the research and writing for this post about nine months ago. But at some point I just go fed up with the ugly divisiveness in the history you're about to read, and I gave it up in disgust. (Warning: this post contains an image of suggested racial violence.) I only picked this project back up about a week ago because a) I may as well get this history out there, and b) I particularly need something productive to focus my mind on at this stage of the COVID-19 lockdown. I hope that the reader finds this post informative!

The History of Detroit's Borders Part I:

The Grosse Pointe Park Border War

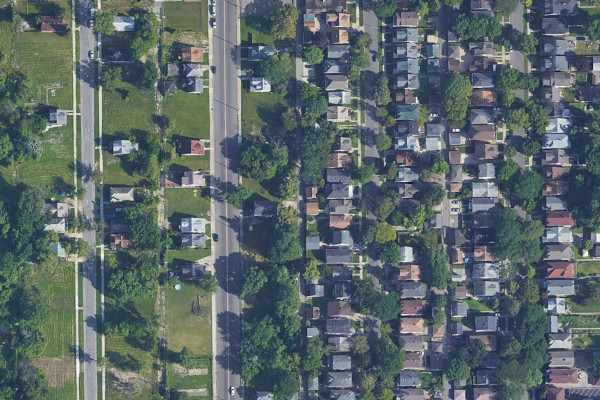

The Detroit-Grosse Pointe Park border near Charlevoix Street.

Our exploration of Detroit's boundaries begins with the two and a quarter-mile long segment where the city meets the western border of the City of Grosse Pointe Park. The line as it exists today was drawn after years of fighting between the two cities. Amazingly, even though this border continues to draw controversy to this day, the roots of this contention can be traced back to events that occurred well more than a century ago.

The Annexation of Fairview

The border between the present-day cities of Detroit and Grosse Pointe Park runs through what was once a municipal village called Fairview. It existed for just a few years early in the twentieth century, located within what was then the Township of Grosse Pointe. Stretching from just west of Bewick Street to Cadieux Road, it was incorporated by the Michigan legislature on May 28, 1903.

Soon after its founding, Fairview planned to construct a sewer beneath Jefferson Avenue beginning at Cadieux Road, running westward until it emptied into Conner's Creek. This threatened to be a public health problem, as Conner's Creek flowed into the Detroit River just upstream from Detroit's waterworks, which supplied drinking water for 300,000 people. In order to halt the project, Detroit's leaders decided to annex enough of Fairview to encompass both Conner's Creek and Fox Creek. The remainder of the village would revert to being an "unincorporated" part of the Township of Grosse Pointe. Under the law at that time, a vote by the state legislature was all that was required to alter municipal borders—and Detroit's delegation in Lansing was more than powerful enough to get their way. The citizens of Fairview had no say in the matter. It wasn't until the adoption of the 1908 state constitution and the passage of the 1909 Home Rule Cities Act that citizens in lands to be annexed were entitled to a vote on the issue.

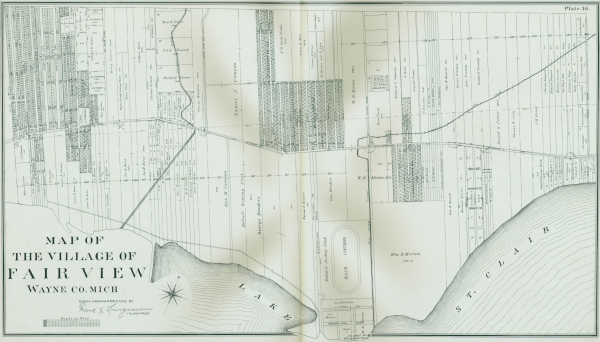

A 1904 map of Fairview. Click here for a larger version.

A 1904 map of Fairview. Click here for a larger version.The state initially passed an annexation bill on March 27, 1907, which took effect the following May 1. However, on October 15, the Michigan Supreme Court declared the law unconstitutional due to a technicality regarding the wording of the bill's title. The legislature quickly reenacted the March bill, only making the necessary change to the title. On October 24, 1907, Governor Fred M. Warner signed the new bill, which took immediate effect.

Measured from the Center or the Edge?

One week after the annexation, the remainder of what had been Fairview was reborn as the Village of Grosse Pointe Park. The state passed Act 534 on May 8, 1907, which defined the village's western boundary as lying "two hundred feet east of the center...of Alter Road." However, according to the text of the the earlier annexation bill, Detroit annexed all of that part of Fairview "lying and being west of a line two hundred feet east of Alter Road," which seemed to imply 200 feet east of the edge of the road, not the center.

This subdivision plat, like all others made after the 1907 annexation, shows

the city border lying 200 feet from the edge of Alter Road, not the center.

This contradiction apparently went unnoticed for decades. Maps made after the annexation show that line the farther east was assumed to be the correct one. When the this area was subdivided, the border ended up running through lots along the west side of Wayburn Street, about 20 feet west of the sidewalk. When the homes were built, owners paid property taxes to both cities. Residents were free to declare themselves citizens of, vote in, and send their children to schools in one municipality or the other. Detroit provided police and fire protection, trash collection, and sewer maintenance to these homes, which had Grosse Pointe Park mailing addresses, as well as access to the suburb's private parks. This made the west side of Wayburn particularly attractive to City of Detroit employees, who were required to live within the city limits at the time. Neal Shine, a former editor at the Detroit Free Press, once wrote that his father, a Department of Street Railways conductor, slept in a back room in his home at 1119 Wayburn every night for the last 21 years of his career in order to comply with the residency law. The situation complicated law enforcement as well: if one of these border homes was robbed, homeowners were told that the appropriate police department to contact depended on whether the robber escaped through the front or the back door.

This municipal ambiguity might have persisted in splendid obscurity had it not been for the City of Detroit's income tax. By 1971, it had come to the attention of Detroit's income tax director, Albert L. Warren, that most residents living on the west side of Wayburn Street never paid the city's income tax, which was then at 2%. In February 1971, Warren billed these families for city income taxes for the years 1968-1970, including penalties and interest, as the law required. But this attempt to collect a mere $100 from approximately each of 100 families did nothing but set off a fifteen-year border war that would ultimately deprive the city of millions of dollars in taxable property.

The War for Wayburn

More than 120 Wayburn residents gathered at the Defer Elementary School auditorium on the evening of February 18, 1971 to protest the tax and to discuss possible ways to get out of paying it. The Wayburnites—at least those who were not City of Detroit employees—considered themselves to be citizens of Grosse Pointe Park, and therefore exempt from Detroit's residency tax. However, some admitted that they were registered to vote in Detroit. ("Tax Demand Stirs Ire of Residents West of Wayburn," Grosse Pointe News, February 25, 1971.)

The affected residents voted to form a representative committee to work with Grosse Pointe Park officials in finding a solution to their problem. They sought input from the Secretary of State's Office, which replied that the west Wayburn residents were free to register to vote in the city of their choice. This confirmed the residents' rights to all the benefits of Grosse Pointe Park citizenship, but the city acknowledged that it still lacked the authority to prevent Detroit from collecting the income tax. Their next step, discussed at a March 8, 1971 Grosse Pointe Park city council meeting, was to petition both cities for a change in the border so that all properties on the west side of Wayburn would lie completely within the suburban municipality.

This petition, along with a supporting resolution from the Grosse Pointe Park city government, was presented to the Detroit city council on November 4, 1971. Grosse Pointe Park officials met with the Detroit Common Council on January 13, 1972 with the ultimate aim of negotiating mutually agreed-upon changes to the border. The issue was referred to Detroit's Corporation Counsel, which reported the following April that the only change that could be made without involving the state legislature would be to annex the entirety of the Wayburn lots to Detroit, since about 80% of each parcel fell within its limits. Detroit directed its engineers to study the exact location of the city line, and the city assessor and revenue department were tasked with estimating the total losses in income and property taxes. Detroit appeared to be taking steps to remedy the problem without taking any real action to surrender an inch of its territory.

Some Wayburn residents voiced their complaints about the tax levy to the Michigan Tax Tribunal. To bolster their case, they claimed that the Detroit border was not 200 feet east of the east edge of Alter Road, but 200 feet east of the center of the road, according to the text in the 1907 village incorporation law. According to their argument, the majority of their properties should have been part of Grosse Pointe Park all along. However, the Michigan Tax Tribunal ruled that it did not have jurisdiction in cases involving boundary disputes.

Wayburn residents argued that the border should be moved 33 feet westward, placing their homes mostly in Grosse Pointe Park.

Wayburn residents argued that the border should be moved 33 feet westward, placing their homes mostly in Grosse Pointe Park.After the Michigan Tax Tribunal failed to help them, the Wayburnites sued Detroit in Wayne County Circuit Court in 1974 in order to block the city from collecting its income tax in the disputed area. They again argued that the border should lie 33 feet west of where it was previously believed to exist. Although the issue was already several years old at this point, it would be another five years until this case was heard in court.

Windmill Pointe Park

All of this attention on the border dispute brought to light another peculiar situation between the two cities that had evidently gone unnoticed for decades. Approximately one-third of Windmill Pointe Park, owned by Grosse Pointe Park, was within the Detroit city limits. That in itself was not unheard of (for example, Detroit owned the Detroit Zoological Park, located in the cities of Royal Oak and Huntington Woods, until the city's bankruptcy restructuring in 2014). What was unusual was Windmill Pointe Park's exclusionary policy of admitting only Grosse Pointe Park residents or their guests, even going so far as to erect fences and a guard post to keep out unwelcome visitors. All the while, Grosse Pointe Park had been enjoying the Detroit portion of the land tax-free.

Ray Rickman, who was then director of the Jefferson-Chalmers Citizens District Council, reported this information to the local media in August 1975. The Detroit portions of the park had been purchased in 1931 and 1965. The portion of the park located in Detroit contained a parking lot and a bath house, constructed in the 1930s. Rickman demanded that Grosse Pointe Park City Manager Robert Slone open the park to Detroit residents. Slone flatly rejected the plea. "If Mr. Rickman wants to use the park facilities," Slone quipped, "why doesn't he move into our city?" ("Park Turns Down Plea To Open Recreation Area To Residents of Detroit", Grosse Pointe News, September 4, 1975.)

(Source: Detroit Free Press, September 4, 1975.)

Rickman pointed out a state law which required, in cases where one municipality owned a park located inside of another, that the property must be taxed if it is not generally open to the public. Rather than allow Detroiters into Windmill Pointe Park, Grosse Pointe Park chose instead to pay approximately $11,500 in annual property taxes on the valuable waterfront land.

Historical Context: The Busing Issue

This border squabble wasn't the only divisive topic fanning the flames of discontent between the city and suburbs in the 1970s. A related and no less controversial fight was being carried out during the first four years of the border dispute.

As the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s brought the racial segregation of American public schools to light, progressives at the time had hoped to bring integration through busing—the practice of redrawing school district boundaries to reduce these imbalances, even if it meant busing students to schools miles away from their homes. In February 1970, Judge Damon J. Keith of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan had found in Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, Inc. that public schools in Pontiac were in fact segregated, and he ordered the school district to produce a plan for integration which would include busing. The following year, the U.S. Supreme Court had upheld the constitutionality of busing in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education in April 1971. The resulting rage among local whites culminated in the bombing of thirteen Pontiac school buses just days before the beginning of the 1971 school year.

Then came the September 27, 1971 decision on Milliken v. Bradley, in which U.S. District Judge Stephen J. Roth found that Detroit Public Schools were racially segregated—about 65% of DPS students were black, but three-quarters of them attended schools that were 90% black. On June 14, 1972, Judge Roth ordered a nine-member panel to devise a comprehensive busing plan covering not just Detroit, but 53 suburban school districts as well—including all five Grosse Pointe communities.

The Grosse Pointe News headline for October 7, 1971.

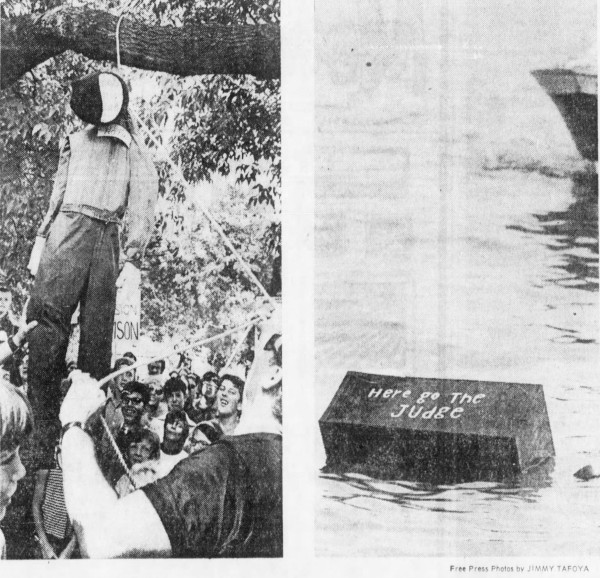

The Grosse Pointe News headline for October 7, 1971.Judge Roth received hate mail and death threats after the rulings. "Not since the early days of the school integration movement in the South has a federal court judge presiding over a case become the focus of such abuse," wrote the Detroit Free Press. "Bumper stickers with comments like 'Roth is a four-letter word' and 'Judge Roth is a child molester' appeared on cars throughout the Detroit area" (DFP, July 12, 1974). Busing opponents held a mock trial of Judge Roth in Wyandotte in July 1972, after which an effigy of him was hanged by the neck. "The stuffed dummy was strung up in Bishop Park and then dumped into the Detroit River in a black coffin labeled 'Here Go the Judge.'" ("Judge Roth Hanged in Effigy After 'Trial' by Busing Foes," Detroit Free Press, July 31, 1972.)

(Source.)

(Source.)The U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Roth's decision in June 1973. However, the case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which struck down cross-district busing in metropolitan Detroit in its decision on July 25, 1974. (Judge Roth did not live to see the final outcome, having suffered a fatal heart attack just two weeks prior, at age 66.) The overturning of Roth's decision came as a relief to many suburban residents. One unidentified Grosse Pointe mother told the Detroit Free Press, "I'm interested in equality, but I do not want my child in the inner city and faced with the problem of the ghetto." ("Most Pleased with Busing Veto," July 26, 1974.)

Fairview's Revenge

The border suit that the Wayburn residents had filed in Wayne County Circuit Court in 1974 was finally heard by Judge Roland L. Olzark of Grosse Pointe on June 28, 1979. The Wayburnites had hired the firm Moll, Desenberg, Purdy, Glover and Bayer, which by then had persuaded the City of Grosse Pointe Park and the Grosse Pointe School Board to join the lawsuit against Detroit. Judge Olzark ruled on October 24, 1979 (the 72nd anniversary of Fairview's annexation) that the border between Detroit and Grosse Pointe Park lay 200 east of the center of Alter Road. Siding with the Wayburn residents, he asserted that the boundary was actually 33 feet west of where it had been believed to exist for most of the twentieth century.

In his decision, Judge Olzark pointed out that the state legislature is the final authority in defining municipal boundaries. The first two laws defining the border—both passed in 1907—were: 1) the law by which Detroit annexed most of Fairview, which ambiguously placed the line "two hundred feet east of Alter Road"; and 2) the law by which the Village of Grosse Pointe Park was incorporated, which drew the border beginning at a point "five hundred feet south and two hundred feet east of the center of Mack Road and Alter Road." According to Judge Olzark, the first unambiguous law was the second one. By his ruling, the city border ran through the back yards of the homes on Wayburn Street, and the plaintiffs were really residents of Grosse Pointe Park.

Above: Text from the Fairview annexation law.

Above: Text from the Fairview annexation law.Below: Text from the law incorporating the Village of Grosse Pointe Park.

Undeterred, Detroit brought the case before the Michigan Court of Appeals. The city's lawyers argued that that the 1950 state law incorporating the City of Grosse Pointe Park (which had only been a village until then) placed the border "200 feet more or less, east of the east line of Alter Road." (This same definition also appeared in the city's own charter, which Grosse Pointe Park voters approved by 1,561-226 on December 11, 1950.) Detroit contended that the doctrine of acquiescence should be employed to let it keep the disputed 33-foot strip of land not included in the 1950 law. But the court's September 9, 1981 decision, written by Judge John H. Gillis of Grosse Pointe Shores, determined that the 1950 law "was for the purpose of incorporating the city, not to change its boundaries nor to annex to Detroit the 33 feet of disputed area. ... [Therefore,] the boundary remained as set forth in Act 534 (of 1907)." Ironically, although Judge Olzark's ruling had essentially moved the border 33 feet, Judge Gillis wrote in upholding that decision, "The fixing of municipal boundaries is a legislative function... The courts will not disturb a legislative determination in this regard... Nor will the courts extend boundaries by judicial construction to include territory outside a legislatively established line."

Attorneys for Detroit appealed this decision to the Michigan Supreme Court, which ruled on May 24, 1982 not to hear the case. That could have been the end of it, and yet the lawsuits kept coming. Some Wayburn residents sued Detroit to recoup income taxes that they never should have paid. Grosse Pointe Park sued Detroit to obtain tax assessment data. Detroit sued Grosse Pointe Park to prevent it from collecting property taxes, because Detroit believed that the Supreme Court decision applied to income taxes only. And so on.

Fifteen years after the dispute began, Detroit's Law Department finally proposed to City Council that a settlement be reached with Grosse Pointe Park. In the resulting deal, the border would be redrawn by an act of the state legislature, placing each previously divided lot wholly within Grosse Pointe Park; and Grosse Pointe Park would pay Detroit five annual installments of $10,000. Both cities dropped all other claims against each other, and every household along the border was now completely inside of Grosse Pointe Park, as was all of Windmill Pointe Park. The suburb voided more than $350,000 in tax claims against Detroit, while adding $2.25 million of property to its tax rolls.

Under Michigan law, if two municipalities agree upon a border change, no additional legislation or vote is required. When the necessary resolutions and other documents were filed with the Secretary of State on November 17, 1986, the change was made official.

The 1986 Detroit-Grosse Pointe Park border.

The meticulously detailed legal description of the redrawn

Detroit-Grosse Pointe Park border nearly fills two printed pages.

Scenes from the Border

The image above shows where Detroit's east border meets the Detroit River, adjacent to where Fox Creek (in the foreground) empties into the river. Lake Saint Clair is in the distance. This photo was taken from Detroit's Mariner Park, facing east toward Grosse Pointe Park's Windmill Pointe Park.

Although the border was redrawn in 1986 with the express purpose of not dividing any individual property parcel, there are however several buildings which straddle the border, because they are constructed on two adjacent lots. One of these buildings, pictured below, is part of Grosse Pointe Park's Department of Public Works facility. The left (west) side half of the building lies in Detroit, and the other in Grosse Pointe Park.

Grosse Pointe Park Department of Public Works, 1005 Wayburn Avenue.

Grosse Pointe Park Department of Public Works, 1005 Wayburn Avenue.Another such building is Shaw's Books, pictured below. The business's entrance lies just within Detroit.

Shaw's Books, 14932 Kercheval.

Shaw's Books, 14932 Kercheval. The city border runs between sheds at the Grosse Pointe Park Farmer's Market.

The city border runs between sheds at the Grosse Pointe Park Farmer's Market. A monument box in the center of Mack Avenue marks the extreme northwest corner of Grosse Pointe Park.

A monument box in the center of Mack Avenue marks the extreme northwest corner of Grosse Pointe Park.The Border Walls

The barricade in Goethe Street, at the Detroit-Grosse Pointe Park border.

The barricade in Goethe Street, at the Detroit-Grosse Pointe Park border.As a lasting testament to the bitterness of the boundary disputes between the two cities, multiple streets which cross the border have been barricaded. Although these structures have been well documented by other researchers (e.g.: The Other America, Unequal Scenes, 63 Alfred), it is worth reiterating some of their history here.

Unlike several other barricated streets, Korte Street is still open to pedestrian traffic.

Unlike several other barricated streets, Korte Street is still open to pedestrian traffic.According to researcher and Grosse Pointe Park resident Katherine Gowan:

Since the 1980s, physical barriers have been erected by Grosse Pointe's city planning department to further isolate the suburb and protect it from Detroit. Of the twelve streets that cross Alter Road, connecting Detroit to Grosse Pointe, four have been physically blocked off, three are without direct access into Detroit, two are one way streets, two run adjacent to the front and rear of the main police station, and the last remaining street [Kercheval] is now [2014] approved to be closed.

Grosse Pointe Park began closing streets near its western limits less than a year following the border's reconfiguration. The city council voted uninimously to close Wayburn at Mack Avenue on August 24, 1987, following a temporary closure of that intersection as well as a nearby alley between Wayburn and Alter. According to the Grosse Pointe News, several Wayburn residents at the August 24 meeting asked the council to investigate closing even more streets and alleys. "A residential alley and a commercial alley, they pointed out, and the one-block section of Goethe between Wayburn and Alter, serve no useful purpose." ("Park council approves Wayburn/Mack closing." Aug. 27, 1987) When the issue of closing Goethe was brought up at a council meeting the following January, the News reported:

City Manager John Crawford and several councilmen felt that the planning commission should study the street closing. Crawford also felt that the residents in the area should be polled and that the Detroit engineering department be consulted since the street flows into the city.

"Can I ask why we would have to consult the city of Detroit?" asked councilwoman Carol Evola.

"We can't just cut a street off at a boundary," Crawford said. "It could create problems for Detroit residents."

("Council approves several parking changes." Grosse Pointe News, Jan. 28, 1988)

Goethe Street was closed several months later, in July 1988, following another petition by Wayburn Street residents. ("Park closes west end of Goethe." Jul. 21, 1988) The next year, 150 citizens of Grosse Pointe Park signed a petition to close Korte Street, making it the largest petition that the city had ever received. The city council permanently closed the street in April 1993, citing the need to reduce traffic. ("Park votes to close Korte." Apr. 8, 1993)

In August 2003, Grosse Pointe Park closed St. Paul Street, which is called Brooks Street in Detroit ("St. Paul will remain dead-end street at Wayburn." Aug. 14, 2003). More recently, Grosse Pointe Park attempted to close Kercheval Avenue by constructing a farmer's market in the middle of the right-of-way in 2014. However, the two cities reached an agreement in 2019 to fully reopen the street, which has since reopened to two-way traffic.

The westbound lane in Kercheval Avenue, unobstructed once again.

The westbound lane in Kercheval Avenue, unobstructed once again.One Generation Passes Away, Another Generation Comes

Photo: Max Ortiz, The Detroit News (Source)

Photo: Max Ortiz, The Detroit News (Source)In 1907, the growing industrial giant of Detroit chomped off and swallowed most of the sparsely populated Village of Fairview. Adding insult to injury, the village charter was revoked in the portion of Fairview that Detroit didn't want. But this very act of hubris would hurt the city in the end. Had the remainder of Fairview been left alone, then there wouldn't be any need to incorporate the Village of Grosse Pointe Park soon after, and the typographical error in its incorporation law could never have been used to justify moving the city's border by 33 feet. Grosse Pointe Park's population of 290 in 1910 had swelled to 15,641 by 1970. By the time Detroit picked a petty tax fight with the residents of Wayburn Street, Grosse Pointe Park was resourceful enough not just to win that battle, but even to take back some of the land that had been annexed in a previous generation.

What does the future hold for this border as the balances of political power and public opinion are constantly shifting? We are probably no better capable of answering this question than the Detroiters of 1907, but there are signs that more residents on both sides of the border are increasingly interested in healing the divide. Some Grosse Point Park residents recently opposed the construction of a public works facility where Wayburn was closed at Mack, saying that it would create yet another barrier at the city border. Other Grosse Pointers are actively calling for the street barricades to be torn down. History is still shaping our borders.

Explore in Detail on Google Earth

As part of this series on the borders of Detroit, I will include a Google Earth file with each post showing exactly where the city boundaries lie, in addition to other relevant information. Click here to download the file "Borders1.kmz", and then open it in Google Earth. The file will appear within the "My Places" folder, as seen in the image above. Click on the check boxes next to each line to show or hide the items from the map. To keep this information available whenever you open Google Earth, select File / Save / Save My Places after opening it.

Excellent piece. I live on the west side of Wayburn St and knew about the changing border but not why. Very cool. I often wonder why Alter Rd between Outer Drive and the GPP border jogs so much. Connor makes sense due to the creek. Any idea why the jogs?

ReplyDeleteWonderful job.

ReplyDeleteThank you for another first-rate, excellent history.

ReplyDeleteGreat article and very informative! I lived on wayburn for years between Kercheval and Charlevoix and my garage was in Detroit and House in GPP if you used 200 ft east of center.

ReplyDeleteI'm confused. Why did the portion of Fairview in Grosse Pointe Township lose its status as a village aftr Detroit incorporated the other half? That wouldn't be the case, today, I know that for sure. Did the legislature revoke it?

ReplyDeleteI was also a bit surprised to read that the Park's city council and manager seem initially uncomfortable with closing off Goethe. That really adds a bit of additional context to the relationship the two cities have. It wasn't entirely black-and-white, pun not intended. It at least seems to show that the Park realized that people from both sides of the city limits crossed it every day for perfectly valid and legal reasons.

BTW, I had no idea the western border of the Park jogs ever-so-slightly east and west dependent upon the width/length of each lot so as not to take in partial lots. I guess I'd always assumed the lots were uniform at the border.

Lastly, man did Detroit lose the roll of the dice when its case was given to a Circuit Court judge from the Pointes...and then a Appeals Court just from the Pointes. lol I actually sympathized with Detroit's position given the evidence. When even the Park's own charter put the line where Detroit was saying it was, why should Detroit have let that go? Anyway, glad they were finally able to work it out.

Curious if the James Robson quoted in the 1975 article is a current City Council member? https://www.grossepointepark.org/james_e_robson/index.php

ReplyDeleteAs a new GPP resident, this history is so valuable as the master planning process begins and we consider the racist legacy of our city, that many residents are ready to change. I plan to share this with City Council.

https://www.gppmasterplan.com/

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete