Hinsdale's Atlas

The first attempt to document all known Native American archaeological sites in the state was Wilbert Hinsdale's Archaeological Atlas of the State of Michigan in 1931. Accepted informants ranged from historical documents to "hearsay sources." Hinsdale and his collaborators examined claims and visited sites to determine plausibility, and concluded that there had been more than 1,068 mounds and 113 earthworks in Michigan, but that fewer than 5% "have escaped mutilation." Outside of Detroit, the largest earthworks in the state were found in Grand Rapids and Port Huron.

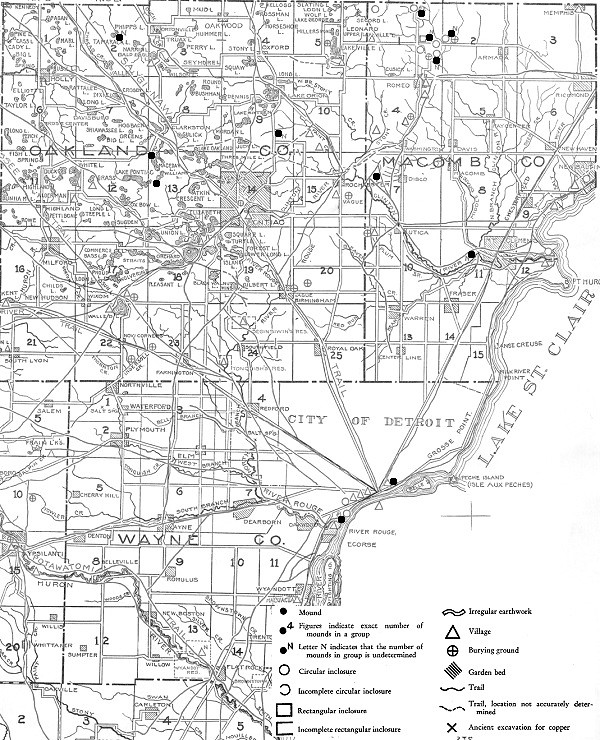

The following sites in Metropolitan Detroit were included in Hinsdale's atlas:

- Wayne county--In addition to the Springwells Mound Group covered in my last post, Hinsdale showed a mound by the Detroit River east of downtown. I have not found any information on it.

- Oakland County--Hinsdale counted five mounds, including "a group in Groveland Township, near the center, and another in the eastern half of Orion Township. The exact number in either group is not a matter of record." A 1960s subdivision in Bloomfield Township contains streets named Indian Mound Road and Indian Mound Trail, but no such features appear near this location on Hinsdale's map.

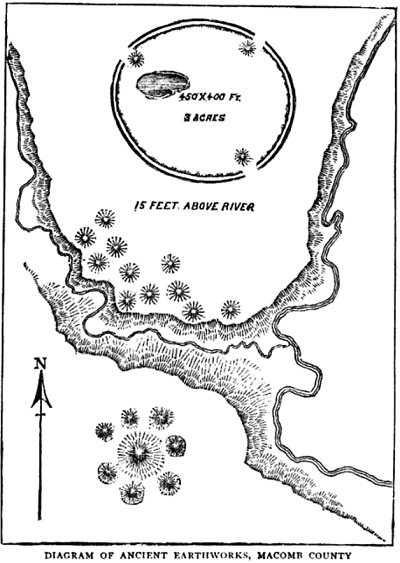

- Macomb County--Here there were once twenty-six mounds, eight circular enclosures, and one rectangular enclosure. According to Hinsdale, "All we know of the extensive inclosures [sic] that had been built in unusual designs in Macomb County is gathered from the literature." In other words, they had all been destroyed.

From Archaeological Atlas of Michigan, by Wilbert Hinsdale. (Source.)

Some of the following mounds and earthworks appear in Hinsdale's atlas, others do not.

The Prairie Mound and Mound Road, Detroit

In the mid-19th century, Hamtramck was a large and mostly undeveloped township with borders extending from Woodward Avenue to Connor's Creek, and from the Detroit River to Eight Mile Road. Around 1865, Civil War veteran Philetus W. Norris purchased a large tract of land in the township close to a sandy hill he called the Prairie Mound. An 1876 history of Wayne County described the location:

"The low but fertile glades and blue joint prairies...were alike the chosen hunting grounds of the prehistoric Mound Builders and Indians... The famous Prairie Mound, of some four acres, was ever a chosen haunt for the Indians, trappers and herders; the site of countless broils and revels, and probably the torturing of prisoners--certainly a bone tumulus of the unknown dead."Norris convinced the Detroit & Bay City Rail Road to come through his property in order to help establish a village there. He wanted to call his settlement "Prairie Mound," but the railroad named their stop "Norris," and the subsequent village plat and post office bore the same name. The original plat contained a Prairie Street and Mound Street, but they have since been renamed Iowa and Davison Streets, respectively. However, the north-south road on the western border of the village was named Mound Avenue. It coincides with today's Mound Road.

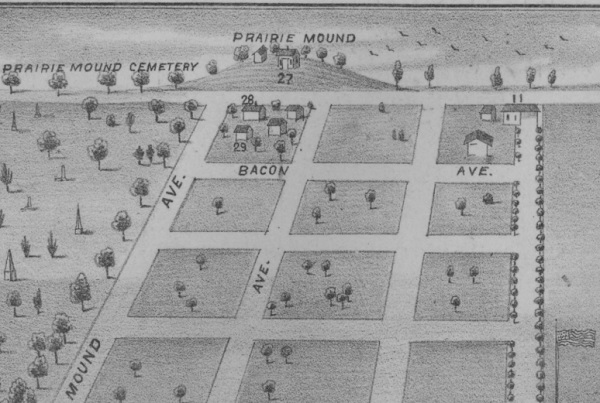

The Prairie Mound would have stood northeast of the intersection of Mound and Seven Mile Roads. It appears on this 1876 "bird's eye view" of Norris:

From Illustrated Historical Atlas of the County of Wayne, Michigan, H. Belden & Co.

Image courtesy University of Michigan. (Source.)

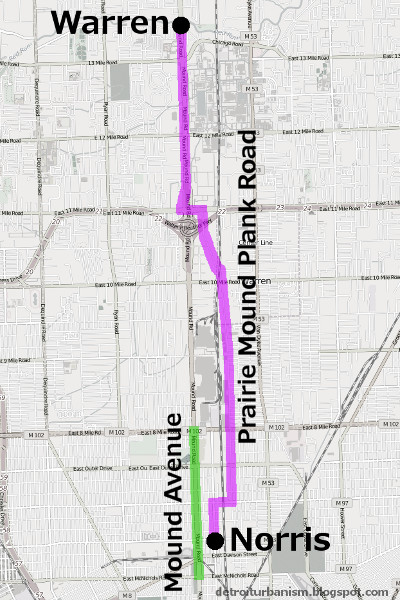

In 1873, Philetus Norris incorporated the Prairie Mound Plank Road Company and was authorized to build this toll road to Warren. To trace the path of the Prairie Mound Plank Road today, begin at the intersection of Nevada St. and Mt. Elliott St. and head north; turn east on 7 Mile Rd., north on Sherwood St., west on 11 Mile Rd., and north on today's Mound Rd. to Chicago Rd., the historic center of the Village of Warren. Today's Mound Road runs from Caniff Ave. in Detroit to Auburn Rd. in Shelby Township, and coincides with the former "Mound Avenue" in Norris and the northern segment of the Prairie Mound Plank Road.

The routes of Mound Ave. and Prairie Mound Plank Rd., circa 1876.

The Prairie Mound was probably not a human-made burial mound. In his 1913 Geological Report on Wayne County, William H. Sherzer wrote:

"The so-called 'Prairie Mound' (in) Hamtramck township, is simply a crescent-shaped sand dune, some 9 to 10 feet high and about 500 feet in length. Upon this William A. Ennis built a house and barn about the year 1865 and came across bones associated with Indian relics,--but whether of the Mound Builder type or not is not known."Whatever the nature of this mound, there is no trace of it left. Standing at approximately this location today is Lou's Coney Island at 19100 Mound Road, Detroit.

Tucker Farm Earthwork, Harrison Township

William Tucker was eleven years old in 1753 when a band of Chippewas raided his family's settlement in Stover, Virginia and killed his father. The Chippewas kidnapped Tucker and his brother, adopted them as members of the tribe, and brought them to their homeland in what is now Clinton and Harrison Townships. When Tucker was allowed to leave the tribe at the age of eighteen, he traveled to Detroit and used his knowledge of Native American dialects to work as a guide and interpreter for Detroit merchants, the British government, and Native American tribes. Twenty years later, in 1780, the Chippewas rewarded Tucker for his friendship and honesty in business with a large land grant on the north side of the Clinton River. He built a log cabin on this land in 1784. The home has since been extensively modified, receiving a brick facade in the 20th century. But the log cabin remains hidden beneath, and appears to be the oldest surviving house built in Michigan outside of Mackinac Island.

The William Tucker House, 29020 Riverbank Street, Harrison Township.

This home became a Michigan State Historic Site on February 23, 1981.

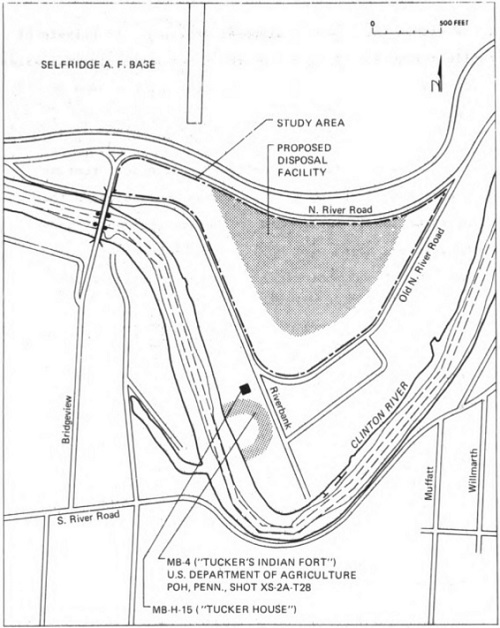

Having been raised by the Chippewa on this land, Tucker knew the area well. The fruitful hunting grounds and the fertile soil made it an ideal place to homestead. In fact, the site Tucker selected had already been an old Native American settlement. He built his cabin next to an old circular earthwork similar to the one found in Springwells. Previous inhabitants of the area had grown maize on the same spot.

The site of Tucker's cabin and the now-lost "fort." (Source.)

Samuel Brown's The Western Gazetteer; Or Emigrant's Directory, published in 1817, noted the existence of the Tucker Farm Earthwork, and Michael A. Leeson's History of Macomb County, Michigan, written in 1882, claimed that there were other such "forts" along the river on land owned by members of the Tucker family. Archaeologist Arnold Pilling, in researching this location (PDF), noted that the earthwork was still visible in an aerial photograph taken in 1940. But by the end of the decade, the entire area had been built over with riverfront cottages.

Northern Macomb County Earthworks

The largest of the circular earthworks of Macomb County was located on a branch of the Clinton River in Armada Township. It encompassed three acres and stood four or five feet high when described around 1830. It was surrounded by a dry moat created by the digging up of the earth for the embankment. A pond lay within the earthwork. According to Leeson's History of Macomb County, south of this "fort" were many small burial mounds, each containing the remains of one individual. On the other side of a nearby stream was a large burial mound, out of which grew a large oak, surrounded by a series of smaller mounds. Not far from this area were found scattered mounds made entirely of stone piled four feet high, each concealing the cremated remains of one individual. All of these earthworks were destroyed prior to 1882.

From Memorials of a Half-Century by Bela Hubbard.

Farther upstream was a smaller circular earthwork with its own set of burial mounds. Edwin P. Sandford of Romeo dug into one of them in 1880 and extracted the skeletons of three adults and three children. Set apart from the smaller mounds was a larger one four and a half feet high with a diameter of twenty feet. A large oak tree grew from this mound which, when cut down, was found to have been 240 years old. When described in 1882, the mound had not yet been greatly disturbed thanks to the massive roots left behind by the felled oak.

New Gnaddenhütten, Clinton Township

In 1781, a group of Christian missionaries from Ohio were arrested and brought to British-controlled Detroit to answer charges of supporting the American Revolution. These were the Moravians, a group of whites and Delaware Indians practicing a form of Protestantism that predated Martin Luther and had been revived by Count Zinzendorf of Moravia several decades before. While some Moravian leaders were in Detroit, the congregants left behind in Ohio were horrifically massacred by American militiamen. Although the Moravians in Detroit were exonerated of the charges of treason, they feared returning to Ohio. With the help of Chippewa Indians and Fort Detroit's commandant, Major Arent DePeyster, they found a new home on the Clinton River, half a mile west of what is today Mount Clemens. They arrived at the site of their future village on July 22, 1782, and named it New Gnaddenhütten.

New Gnaddenhütten was founded close to this spot on the Clinton River.

Brown referenced this location in his Western Gazetteer:

On the river Huron [the old name for the Clinton River], thirty miles from Detroit, and about eight miles from lake St. Clair, are a number of small mounds, situated on a dry plain, or bluff near the river. Sixteen baskets full of human bones, of a remarkable size, were discovered in the earth while sinking a cellar on this plain, for the missionary.Strangely, the diary of David Zeisberger, the Moravians' minister, did not mention any mounds. But he did write that his group "found many traces that a long time ago an Indian town must have stood on this place," including "little hills where corn had been planted, but where now is a dense wood of trees two to six feet in diameter." Perhaps these "little hills" were exaggerated into "mounds" in the twenty years between Zeisberger's landing and Brown's research.

The Moravians' village was near the south bank of this bend in the Clinton River.

Also absent from Zeisberger's diary is an account of unearthing a large number of bones. Archaeologist Arnold Pilling has speculated that the Moravians very well could have encountered a mass burial since it was the site of an ancient village, but no cellar was dug for the mission. Instead, the cellar in question may have been one of the "out cellars" mentioned by the Moravians when describing improvements made to the land several years later (see "Six Archaeological Sites in the Detroit Area," Michigan Archaeologist, vol. 7, Sep. 1961).

Riviere au Vase, Chesterfield Township

Bernard Trinity's Many Yesterdays, published in 1986, recounts the stories told by those who grew up in Macomb County in the early 20th century. A Mrs. Mary Quine recalled attending the Green School, a one-room schoolhouse on Sugarbush Road in Chesterfield Township. "What she remembered especially well about the Green School," wrote Trinity, "was the Indian cemetery that was located on the sandy knoll in back of the school. At noontime school children often gathered on the sandy knoll to play or dig for Indian treasures. Marie frequently joined them." A Mrs. Hazel Stevens recounted the story of Martin Green, who lived across from the school, frequently unearthing skulls in his field and placing them on his fence. After the fence pickets accumulated dozens of skulls, a neighborhood meeting was called to ask Green to remove them. Green stored the bones in his attic, Trinity wrote, but "whatever happened to Mr. Green's collection of skulls and human bones was never explained by the members of Green's family or neighbors." These incidents have been corroborated by other longtime residents of the area, according to Chesterfield historian Alan Naldrett.

The site of the sandy knoll on an 1818 government survey of Chesterfield Township.

The Chippewa held the land as a reservation per the 1807 Treaty of Detroit.

It and other local reservations were ceded to the U.S. in 1836 when they

were traded for a thirteen square mile reservation west of the Mississippi River.

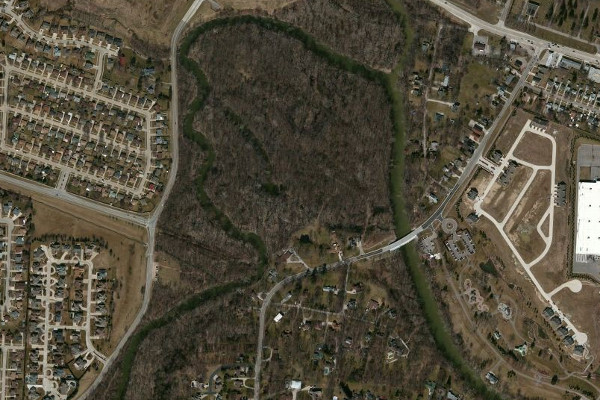

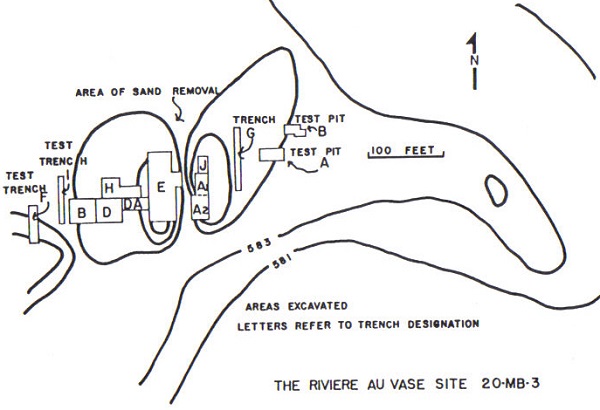

Whether the sand ridge behind the Green School was a natural formation or was partly human-made isn't known, but it had clearly once served as a significant Native American burial ground. Residents reported that part of the sandy knoll was removed for commercial purposes in 1927, upon which more skeletons were uncovered. This sand ridge, located on the south bank of the Riviere au Vase (now called Auvase Creek), was excavated in the summers of 1936 and 1937 by Professors Emerson Greenman and George Quimby of the University of Michigan. Remains from at least 350 individuals were removed. Samples taken from the site have been radiocarbon dated to between 900 and 1200 A.D.

From Late Woodland Cultures of Southeastern Michigan by James E. Fitting.

Image courtesy Alan Naldrett.

In his 1965 report on the 1936-1937 excavations, archaeologist James Fitting decries the poor quality of the record keeping associated with the digs and the subsequent site destruction. "After the University of Michigan excavations," he wrote, "the site was subject to much indiscriminant collecting. Many burials and features were destroyed and artifacts removed with no record of provenience. Only one other excavation was undertaken in a controlled manner and adequately reported. This was done by Mr. Jerry DeVisscher" in 1957.

One and a half miles to the northeast of this location, on the southwest bank of the Salt River, was a circular earthwork enclosure with an entrance facing the river. A white oak tree whose truck had a diameter of three feet grew in the middle of it as of 1837. I have not found any reference to this outside of Leeson's History of Macomb County and Robert F. Eldredge's Past and Present of Macomb County, Michigan.

Undisclosed Location, Southeast Michigan

We drove slowly along the dirt road, trying to spot something, anything through the forest. Even with the summer foliage gone, we couldn't make out any unusual mounds or hills.

But this was the right place. Hidden among the trees was, I believe, a circular earthwork--an "Indian fort"--similar to the one that used to lie in Springwells. The similarity between a 19th century eyewitness description and a shape faintly visible on a 20th century aerial photograph on that very spot couldn't be a coincidence.

Signs were posted nearly every ten feet around the property: "No Trespassing / No Hunting" -- "No Trespassing / Violators Will be Prosecuted" -- and a few weathered scraps of wood with hand-painted lettering: "NO TREZ." Maybe sneaking into the forest was a bad idea. We decided to park the car on the public road and walk up the long, muddy, pothole-filled driveway to speak directly to the property's residents. They will appreciate the direct, honest approach.

A dog chained to the front porch of the careworn house barked when we approached. I waved to a man I saw walking from the house to a pickup truck, but the Unsmiling Man did not wave back. He started his vehicle and drove towards us, and we waited for him rather than approach any farther. The silhouette of a second man appeared in the doorway.

The Unsmiling Man stopped his truck next to me with his window down. "Hi," I said, "I am a ... researcher of history." (Yes, that will do...) "I came across some historical records of an old Indian fort located on this land. The--"

"No." The Unsmiling Man was oddly unphased that someone had just walked up to his house talking about an Indian fort. Then, in a tone that was neither rude nor polite, yet unambiguously demarcated The End of the Conversation, he added, "Stay out of the woods."

The direct, honest approach did not work that day. All that was left to do was turn around and walk back down the long, swampy driveway, with the Unsmiling Man's truck following us all the day down to the road. We did not park near the driveway, but a short walk down the road. As we approached our car, a different pickup truck passed us from behind, turned around where our vehicle was parked, and then drove past us again. Was this the shadowy figure we had seen on the porch, protecting the non-existent Indian fort that isn't in the woods that we definitely shouldn't go into?

Although I was disappointed to have missed out on the chance to commune with the past amid the ruins of a lost civilization, let's face it--these events are essentially confirmation that prehistoric earthworks are very much intact right here in Metropolitan Detroit. And I am happy to see that they are hard to find, well hidden, and well protected.

Wait, should I just have bribed him instead?

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteExcellent article! Keep them coming!

DeleteExcellent article! The "forts" you describe sound to be exactly like the ones I recently wrote about seeing, up north in Ogemaw County...

ReplyDeletehttp://www.nailhed.com/.../ancient-echoes-from-forest.html

That's awesome! Seeking out and actually finding one of those in person must have been an incredible experience. I don't have the exploration experience you do, so I might just have to go to Ohio in the summer to see some in person. Thanks for the link!

DeleteGreat article! Is the other mound in Detroit besides the Springwells mound the one by Fort Wayne? It's mentioned in a number of accounts, including here: http://www.historicfortwaynecoalition.com/NAConway.html

ReplyDeleteand here:

http://detroittechnomilitia.com/main/index.php/techno-history/detroit-history/120-detroits-curse-indian-burial-mounds

Alan

The Springwells Mound Group in southwest Detroit consisted of at least five mounds and one circular earthwork. One of the five mounds was the same one described in those links that is still standing by Historic Fort Wayne.

DeleteOk, thanks.

DeleteAny idea where on the Salt River the enclosure was in Chesterfield? I found an article on it once and was fascinated by it. This is the only other reference I have seen. I figured it was near Callens Road based on the description I found.

ReplyDeleteThe only sources I found don't offer too much specific information. Michael A. Leeson's "History of Macomb County" (published 1882) at the bottom of page 151, says, "There were the remains of an old fort on the bank of a streamlet flowing into Salt River, in 1837. The walls were circular with a gateway leading to the stream. At the time of its exploration by Robert P. Eldredge, a white oak tree, at least three feet in diameter, sprung from the very center of the fortress, but whether this was planted by the builders, or grew up since the fort was constructed, the explorers were unable to state."

DeleteRobert F. Eldredge (apparently a relative of the Robert P. Eldredge mentioned above) published "Past and Present of Macomb County, Michigan" in 1905. On page 546 he wrote, "On the southwest bank of Salt river not far from its mouth was located on of these forts which inclosed some three acres. The gate or mouth of the inclosure appeared opposite the river, and directly across from the same was a cornfield, where thousands of little hills, the result of corn cultivation, were apparent even as late as 1827."

Unfortunately, these two books are the references I've ever found to this fort.

After everything ive read im prettu sure i live exactly where this description is saying

Deletehave you explored the area much? I have been to the old fort and kayak around that area of salt river for fun! im glad they put a park in at the dead end on hooker rd.

DeleteAwesome post.Thanks For share this post with us. We would wish to share with you a prime four list of accessories things, that area unit essential for the winter season trends. you'll Friendship Bracelet beat the cold and dark days with these merchandise, as a result of they need a practical role besides the modern one:we wear to decorate up and build these outfits shine and shimmer!

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for Great amazing blog. I am very satisfied to see your article. Keep up the good work. What are you waiting for? Contact us for more information website What is the entrance gateway to University of Michigan? & Call 9718417575 for more data/to approach.

ReplyDeleteI have a map from 1929 i want to share/ post i think pilling had it backwards...i think im living on all the descriptions found thus far and are out there

ReplyDeleteVery well could be backwards.

DeleteI am finding the surveyor for Bruce, Romeo, and Washington had it misconstrued.

along with the fact they gave no legitimate coordinates but gave great detail what each site possessed.

I have got a weird theory but i feel there is something that has been hidden from us in the Macomb County area.

The mention of large skeletons, low-brow skulls found.

intersecting cultures, the whole area here is interesting.

Hi, do you know the address of the fort wayne mound in detroit? Im having issues finding it on google

ReplyDeleteTry these coordinates: 42.297926597075644, -83.09765414475633

DeleteHi, I hope you still get notifications to this post you've made.

ReplyDeleteI live in Macomb County, specifically Romeo, Bruce.

I have been doing a great deal of reading and research in this area because it is all so elusive.

I do believe I have found the location mentioned and described by Bela Hubbard.

it was noted the tree was cut down, but removal of the stump and root system proved too difficult, and it is said that it can still be seen to this day, speaking 1882

I have compared aerial photos of the area and plat maps.

The pond appears for one year and then it continues to dry and eventually trees hide it away.

but the mound, and stump can still be seen on google earth 2023.

there is a lot of interesting things noted about the area, but no locations or coordinates are ever given.

Do you think the state actually knows of a still standing mound, it is plowed around and has not been removed, but I am worried it may not be known and properly preserved.

You might be interested to discuss these Macomb earthworks with Tom Stanis (https://www.tomstanis.com/map-of-estates--water-mills.html) . He and I had exchanged emails a couple years ago, and he had spoken to an archaeology professor at Oakland University who had visited the site and says that the earthen "fort" in Bruce Township was still intact. The state does know about these things, but the information is well guarded in order to safeguard their preservation.

DeleteIn 2000 through 2003, I worked with a neighborhood group to try to protect old-growth forest and extensive wetlands on the proposed Secluded Woods and Lakeview Estates residential developments southwest of 23 Mile and Jefferson in Chesterfield Township. The site was part of an Indian reservation and also the location of the "Wolf Site", a native American occupation site and burial ground dating back to around 1200 or earlier. I don't recall all the details but this may have been associated with the Green School site as it was not far away. After about 3 years of trying almost everything, SHPO wrote-off on the site and it was developed. We managed to protect a little extra area but not because of the Wolf Site. See links: https://www.angelfire.com/falcon/swat1/wolfsite.html

ReplyDeletehttps://www.angelfire.com/falcon/swat1/

Bill Collins

mail@ThumbLand.org