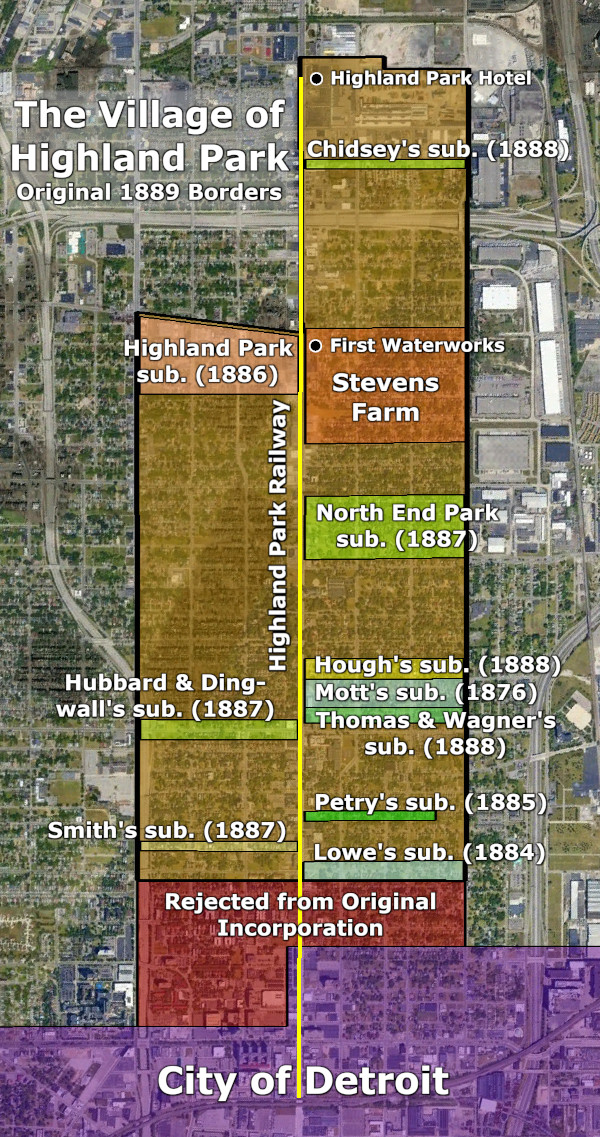

This blog post started off as another entry in the "Detroit Borders" series, with this installment examining the city's border with the City of Highland Park. But after diving a little too deep into the history, I ended up with more material than could fit into a single article. So now I present to you a series on Highland Park, beginning with the following long and detailed development history, covering its founding as a village in 1889 up through Ford Motor Company's purchase of a factory site here in 1907.

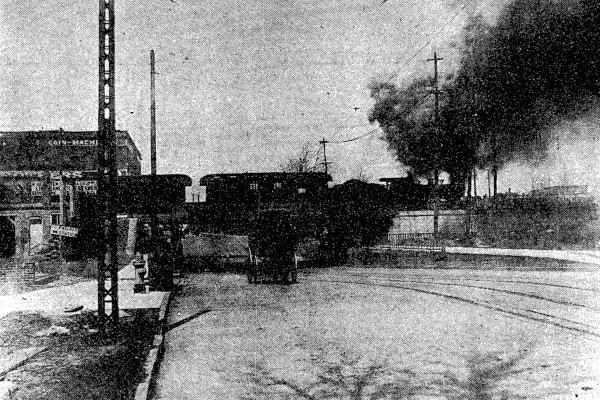

Facing south toward Woodward Ave. and Victor St. in 1908.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

As early as the 1870s, there was a movement to improve the area surrounding Woodward Avenue north of the crossing of the Grand Trunk Railroad, which for decades was the northern barrier between city and country. In April 1875, a group of interested businessmen and residents met at the Five Mile House, a tavern on Woodward located near what is now Sears Street, to discuss possible future projects, such as establishing a permanent home for the Michigan State Fair, building a driving track for horses, grading Woodward Avenue, planting trees, and otherwise improving the area in what is today Highland Park. ("Woodward Avenue." Detroit Free Press, Apr. 2, 1875.) This area was then known as Whitewood, an unincorporated rural farming community straddling the border between Greenfield and Hamtramck townships. The village of Highland Park was still more than a decade away, as the man who was the main driving force behind its establishment had his attention focused on other matters.

The Captain

(Hathi Trust)

William Henry Stevens was born September 14, 1820 in Geneva, New York. He began to learn locomotive engineering as a teenager, and by age 18 he was operating a passenger train. Afterward, he worked as a steam engine fireman on both trains and steamboats, eventually commanding vessels which plied the waters of the Great Lakes from Chicago to Buffalo. From then on, he was often respectfully addressed as "Captain Stevens." In the early 1840s he settled in the Upper Peninsula, where he was a successful prospector in both timber lands and copper mining for more than twenty years. It was during this period that he married Ellen Petherick, a native of England, in Copper Harbor in 1859. After a brief retirement in Philadelphia, Captain Stevens was living in Detroit by 1870. His ambition undiminished, he invested and took an active interest in multiple Detroit institutions, most notably Parke, Davis & Company in 1871. By 1874, Captain and Mrs. Stevens were living in a handsome brick mansion on Woodward Avenue, where Detroit's Main Library stands today.

Captain William H. Stevens' Detroit home on Woodward Avenue in 1887.

Captain William H. Stevens' Detroit home on Woodward Avenue in 1887.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Captain Stevens remained actively engaged in mining, exploring the Rocky Mountains for valuable mineral deposits. While prospecting around the former gold-mining town of Oro City, Colorado, he and metallurgist Alvinus B. Wood discovered that a heavy, black sand which had been great annoyance to mining operations there was actually rich in lead and silver. Their discovery triggered the Colorado Silver Boom and made Captain Stevens fabulously wealthy. In 1880, Captain Stevens co-organized the Iron Silver Mining Company, whose investors were mainly Detroit capitalists, including John S. Newberry, James McMillan, and Senator Thomas W. Palmer.

By 1881, sixty-year-old Captain Stevens was spending less time out west and focusing more on his life in Detroit. He had purchased a 113-acre estate which he called "Highland Park," due to its slightly higher elevation (of about 50 feet) over downtown Detroit, five miles away. Captain Stevens bred livestock on the property, located in Hamtramck Township, and experimented with drilling for water and gas. The natural advantages of the location enabled it to form the nucleus of a village, by which the Captain could escape city taxes, control local streetcar franchises, and reap a fortune in land speculation.

The Highland Park Railway

The boundaries of Detroit have historically been limited by the transportation methods available at the time. When the borders were extended in 1857, all of the city was within three miles of Campus Martius. Horses were mostly used to move heavy loads and the wealthier class of citizens, but for everyday personal mobility, most people simply got around the city on their own two feet. The first horse-drawn street cars appeared in 1863, allowing the city gradually to expand to the boundaries first reached in 1885. However, the four-mile range of horse-drawn streetcars practically put a limit on Detroit's urban growth.

Breaching this barrier and making Highland Park accessible required an advance in technology: the electric streetcar. On May 12, 1886, Captain Stevens co-founded the Highland Park Railway, one of the very first working electric streetcar lines in the United States. (That same year, similar systems were introduced in Montgomery, Alabama and Scranton, Pennsylvania, as well as on Detroit's own Dix Avenue route.) Other investors in the enterprise included Fremont Woodruff, a lawyer who was also Stevens' son-in-law; Frank E. Snow, vice-president of Third National Bank (of which Stevens was president); William A. Jackson, an executive at the Detroit Electrical Works; and John B. Corliss, recently the Detroit City Attorney.

(insulators.info)

(insulators.info)The engines driving the streetcars were a recent technological innovation, designed by 27-year-old Detroit inventor Frank E. Fisher. His design greatly reduced inefficiencies seen in other available motors, until the invention of three-phase electric motors several years later. Fisher predicted that the "spectacle of jaded, worn-out horses pulling heavy cars would no longer be seen on the streets." ("Give the horses a rest." Detroit Free Press, Oct. 18, 1886.)

The Highland Park Railway's car "Ampere" on Woodward Avenue, with trailer. Other cars included "Franklin," "Faraday," and "Volta." All were manufactured by Pullman Car Works of Detroit.

The Highland Park Railway's car "Ampere" on Woodward Avenue, with trailer. Other cars included "Franklin," "Faraday," and "Volta." All were manufactured by Pullman Car Works of Detroit.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

The company obtained the rights to occupy Woodward Avenue from Detroit and Greenfield Township, which had jurisdiction over the west side of the road, where the tracks would be laid. A small station was built at the southern end of the line, where Woodward crossed the Grand Trunk Railroad. This is the spot where Detroit's horse-drawn streetcar service ended, just south of Baltimore Street. The Highland Park Railway ran more than three miles north before looping back at a point north of Manchester Street.

The route of the Highland Park Railway and the borders of surrounding municipalities, as they appeared in 1886.

The route of the Highland Park Railway and the borders of surrounding municipalities, as they appeared in 1886.By October 1886, the system was in regular operation, opening hundreds of acres of rural farmland for suburban development, which was the reason for the Highland Park Railway's existence. According to historian Ken Schramm, author of Detroit's Street Railways, the Highland Park Railway "published a real estate promotional booklet highlighting its many fine services."

Once the electric streetcar line proved its ability, Captain Stevens tore down the Five Mile House which had stood at the northern end of the line and built a small summer hotel in its place. Designed by Detroit architect Henry Englebert, the Highland Park Hotel was open for business by May 1887. Originally containing just seven sleeping rooms, the establishment was "intended to be merely a road house for the accommodation of the wealthier class of persons, who drive in that direction and desire a meal before their return." But business had so far surpassed expectations that plans were already underway for an expansion by the time a fire destroyed the building on October 26, 1887. ("Nothing left but the chimneys." DFP, Oct 27, 1887.) The hotel was immediately rebuilt and continued to be popular destination.

The Highland Park Hotel (left) and attached dance hall, date unknown.

The Highland Park Hotel (left) and attached dance hall, date unknown.(Virtual Motor City)

First Subdivisions

When Detroit burned in the Great Fire of 1805, Congress granted 10,000 acres of federal land to the city in order to raise funds to build a new court house and jail. This block of land, known as the Ten Thousand Acre Tract, was surveyed into 60 "quarter sections," each containing one-quarter of a square mile, shaping the development of borders and streets in the area that would become Highland Park and Hamtramck. A post office was established here in 1873 bearing the name "Whitewood," as the quiet farming community was then known.

The 10,000 Acre Tract in 1876. (University of Michigan)

The 10,000 Acre Tract in 1876. (University of Michigan)The first part of Highland Park to be subdivided into village lots was in Quarter Section 16 of the Ten Thousand Acre Tract. The subdivision consisted of all of that quarter section lying south of Glendale Avenue. Glendale, once known as English Settlement Road, was still just a country lane, established along the ridge of high land which gave the area its name. The subdivision, simply called "Highland Park," consisted of 216 lots located just across Woodward Avenue from Captain Stevens' farm. Wayne County officially recorded the subdivision plat on November 11, 1886. Landowners listed on the document included William Jackson, Frank Snow, John Corliss, John B. Price and DeForest Paine.

Highland Park, Subdivision of Part of 1/4 Sec. 16, Ten Thousand Acre Tract, South of Glendale Ave.

Highland Park, Subdivision of Part of 1/4 Sec. 16, Ten Thousand Acre Tract, South of Glendale Ave.The second subdivision to open in the future village was North End Park (not to be confused with today's North End neighborhood). The Detroit realty firm Hunt & Leggett marketed the property, advertised as "one of the highest and dryest pieces of lands about the city." (Advertisement. DFP, Nov. 9, 1887.) The subdivision, lying just south of Captain Stevens' farm, encompassed Englewood, Rosedale, and Harmon streets. Hunt & Leggett inserted deed restrictions requiring a minimum construction cost of $1,500 for houses, and banned "saloons and business establishments" from the subdivision altogether. Lots came with some improvements, including shade trees, graded streets, and access to "a new system of local waterworks being put in by Capt. W. H. Stevens ... assur[ing] an ample supply of pure water." ("North End Park." DFP, May 15, 1887.) As a sales promotion, each purchaser of a lot was entered into a contest to win a two-story house in the subdivision, designed by local architect William G. Malcomson (pictured in the advertisement below). The drawing was supposed to occur after all of the lots were purchased, however parcels would remain unsold for years.

North End Park advertisement, Detroit Free Press, May 15, 1887. (freep.newspapers.com)

That summer, Captain Stevens opened an 80-acre tract of old-growth forest on his Highland Park farm as a semi-public park. In July, he dedicated the space to be used as a "picnic and meeting ground to be free for all educational, religious, benevolent and moral purposes" for the remainder of his life. ("Highland Park dedicated." DFP, Jul. 4, 1887.).

A new group advocating for infrastructure investments in the area was organized in March 1888, known as the Woodward Avenue Improvement Company. They called for the installation of street lights, sewers, and water mains from the city limits up to the Highland Park Hotel. ("The north end of Detroit will be completely citified." DFP, Mar. 15, 1888.) Increased activity in the suburban real estate market in the area followed. In the original Highland Park subdivision, the Detroit Free Press noted that homes costing "from $1,700 to $2,500 are being put up on the lots by the purchasers." ("Far too conservative." DFP, Jul. 29, 1888.) The Malcomson-designed prize home in North End Park was reportedly under construction by August, as were two miles of six-foot sidewalks throughout that development. ("Moderately active." DFP, Aug. 26, 1888.) Advertisements the following month claimed that several more houses were under construction there. Wooden sidewalks were laid along Woodward Avenue as far as the Highland Park Hotel, gradually giving the rural community a more village-like appearance. That summer, the Free Press reported:

Plans for laying sewers are being considered, but further improvements will probably be delayed until after the next session of the [state] legislature. The idea is to have the property beyond the city limits and extending out to Highland Park incorporated as a village, thus giving it a distinct government. Once this was accomplished extensive improvements would be made and a suburban city built up. ("A summer siesta." DFP, Jul. 8, 1888.)

Woodward Avenue at the Grand Trunk Railroad crossing—the longstanding northern divider between Detroit and the countryside beyond—in 1882.

Woodward Avenue at the Grand Trunk Railroad crossing—the longstanding northern divider between Detroit and the countryside beyond—in 1882.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

"In no way or sense a public necessity"

State Representative Tyler John Wells of Greenfield Township introduced the legislation to incorporate the Village of Highland Park as House Bill 284 at a session of the Michigan House of Representatives on February 14, 1889. The bill was referred to the legislature's committee on municipal corporations. In the meantime, the legislature received petitions both for and against the new incorporation. Representative Wells presented petitions from both sides on March 12, including one from Senator Thomas W. Palmer "and 79 others, taxpayers in the territory affected" in favor of the village. The committee on municipal corporations returned an amended version of the bill to the House on March 15, and recommended its passage. The House approved the bill by 76-0 that same day and forwarded it to the Senate, where it was referred to that body's committee on cities and villages.

At this stage, Senator Anthony Grosfield of Detroit presented another petition against the village incorporation on April 3, which property owners and tax-payers in the affected area had sent to the legislature, citing the following reasons:

First, That the majority of the residents within said limits are opposed to and do not desire to be so incorporated.

Second, That such incorporation would be detrimental to our interests as property owners.

Third, That such incorporation would burden us with increased taxes, without adequate returns or benefits therefrom.

Fourth, That such incorporation would force many of us to sell the small holdings and farms upon which we now depend for a living.

Fifth, That such incorporation is in no way or sense a public necessity, and will be of no benefit whatsoever.

Sixth, That we respectfully call the attention of your honorable bodies to the affidavits hereto attached as setting forth certain facts bearing on the mutilation and false use of a petition of remonstrance previously forwarded, to be presented to the honorable, the House of Representatives.

Senator Grosfield produced an additional petition against the village on April 4. According to the Free Press, "Quite a delegation of citizens of Hamtramck [Township] and Greenfield were heard to-night in opposition to the bill to incorporate Highland Park as a village. They denounced and supported their denunciations by affidavit, setting forth that unfair advantage had been used to obtain the passage of the bill in the House." ("The boulevard bills." DFP, Apr. 5, 1889.) Property owners Robert Stewart and William McFarlane, respectively of Hamtramck and Greenfield townships, appeared at the state capital on April 9 to oppose the village proposal. ("Legislative doings." DFP, Apr. 10, 1889.) That day, the committee on cities and villages returned an amended version of the bill to the Senate, where it would be further debated.

The lawmakers came to a compromise of sorts by April 16, by which it was decided that the borders of Highland Park would not reach all the way down to Detroit, but a buffer of unincorporated land would remain. The bill was sent back to the Senate's committee on cities and villages, which returned the additionally amended bill that day. The Senate concurred with the amendments and voted 21-0 in favor of the bill. It was returned to the House, which concurred with the Senate's amendments and approved the legislation by 71-0. Governor Cyrus G. Luce signed the bill into law on April 17, as Act 371 of 1889, and the Village of Highland Park was born. However, its borders had a completely different configuration than they do today.

The village consisted of the following tracts of land: in Greenfield Township, all of Quarter Sections 25, 36, and 45 of the Ten Thousand Acre Tract, plus the part of Quarter Section 16 lying south of Glendale Avenue; and in Hamtramck Township, all of Quarter Sections 4, 17, 24, 37, and 44, in addition to a six-acre tract attached to the north side of Quarter Section 4.

Municipal boundaries in the Ten Thousand Acre Tract in 1889.

Municipal boundaries in the Ten Thousand Acre Tract in 1889."We shall take care who comes into our community."

Soon after the Village of Highland Park came into existence as a legal municipality, an anonymous village authority described to a Free Press reporter some of the big improvements in store for the community:

We shall make every necessary public improvement in the way of sewers, sidewalks, surveys, grades, etc., upon the most economic basis. That is, it will be done more in the way of private business than after the public system, and $1 will thus go as far as $2 expended on a political partisan plan. Men who work for us will work for their money, and not because we expect them to vote for us. When this ground work is finished we shall take care who comes into our community. The resident must be one whose ideas are in consonance with ours; thus we shall avoid high city taxes for police, fire engines and the like, and every man will be an aid instead of a burden to the community. There will be exceptions, of course, but you may be sure of one thing—birds of a feather flock together—and a disreputable class of citizens very soon seek their kind when they find no congeniality or support in their neighborhood." ("Detroit property." DFP, Apr. 28, 1889.)

The village held its first election at the blacksmith shop of August Seiss on Woodward Avenue on May 6. The new village council met for the first time three days later, awarding contracts for sidewalk construction and discussing plans for a municipal building. Contracts for new homes in the Highland Park and North End Park subdivisions were announced at this time, as were the Highland Park Railway's plans for doubling the capacity of its streetcars, and beginning 20-minute service in the village. ("Detroit's suburbs." DFP, May 12, 1889.)

Some homes had already been built in the village's first two subdivisions, Highland Park and North End Park. Three additional subdivisions had been platted the previous year, including Chidsey's (north side of Gerald Street), Thomas & Wagner's (Leicester Court), and Hough's (Westminster Avenue). By May 1889, Hough's subdivision was optimistically advertising that "sewers will be built before long." Later in the year, another new subdivision—Duffield & Dunbar's—opened in the southwest corner of the village, advertising properties for a home or "for an investment," predicting a "large increase in real estate values" in the area.

Ad for Duffield & Dunbar's subdivision, Detroit Free Press, Nov. 24, 1889. (freep.newspapers.com)

After the village council ordered sidewalks to be built along Woodward Avenue, Captain Stevens declined to use wooden planks for the half-mile portion which ran alongside his farm, but insisted on expensive but durable asphalt. Convinced that he could build a village waterworks on his property, he constructed a brick building over deep wells drilled at what is now Colorado Street, installing an 80-horsepower, steam-powered pump in the autumn of 1889. He had also contracted with Henry Engelbert (the architect of the Highland Park Hotel) for a residential/retail building on Woodward Avenue, and there was discussion of building a school for the village. Old Whitewood was rapidly disappearing, with even the local post office officially changing its name to Highland Park on June 27, 1889.

The home of Charles H. Ketcham, 80 Highland Ave. When Ketcham died in 1924, his obituary claimed he lived in this house for more than 36 years, placing its date of construction around 1888.

The home of Charles H. Ketcham, 80 Highland Ave. When Ketcham died in 1924, his obituary claimed he lived in this house for more than 36 years, placing its date of construction around 1888.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

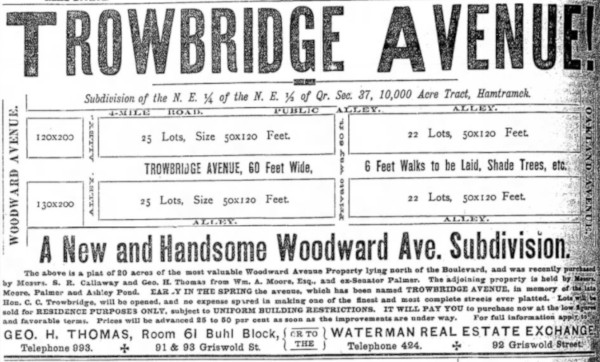

More than a dozen new subdivisions opened within the village the following year, 1890. In order to make Highland Park the exclusive suburb it was intended to be, realtors targeted the wealthier class of buyers by adding deed restrictions which permitted only the construction of single-family houses, which had to meet minimum construction costs. Advertisements for Highland Park subdivisions typically emphasized their spacious lot sizes, proximity to transit, and the "high and dry" quality of the land.

Advertisement for Callaway & Thomas' Subdivision, Detroit Free Press, Feb. 9, 1890. (freep.newspapers.com)

Advertisement for Callaway & Thomas' Subdivision, Detroit Free Press, Feb. 9, 1890. (freep.newspapers.com)An early 1890 advertisement for the original Highland Park subdivision claimed that water pipes were about to be laid in Glendale and Highland avenues, and another ad months later claimed that 21 houses had been completed in that development. Hamilton Avenue was established along the village's western border up to Glendale Avenue that year. Rudimentary improvements were made to the new subdivisions cropping up along both sides of Woodward Avenue. "Sidewalks are being laid on Hazelwood, Trowbridge, Blaine, Gladstone, Euclid, and Pingree avenues, about six miles of which will soon be complete," the Free Press reported, "and shade trees are being transplanted by the hundreds daily." ("A healthy market." DFP, Apr. 20, 1890.)

The Annexation of 1891

It did not appear at all likely that the village council of Highland Park was about to provide water, sewers, police, fire protection, and all other city services in all of the subdivisions cropping up—and few property owners would build without them. It was far more realistic to simply annex territory to Detroit. This idea did not appear to chagrin Highland Park's investors. In fact, it appears to have been their plan all along.

A sketch of proposed annexations from Springwells, Greenfield, and Hamtramck townships from the February 9, 1891 edition of the Detroit Free Press. (freep.newspapers.com)

In September 1890, a group of property owners in and around Highland Park—including Captain Stevens and several real estate dealers—established the North Woodward Avenue Improvement Association. At its inaugural meeting, realtor Joseph R. McLaughlin declared: "That portion of Detroit beyond the [Grand Trunk] railway tracks and [Grand] boulevard is destined to develop into a suburb of great importance." McLaughlin listed six objectives to help accomplish this goal, including "the extension of the Woodward avenue sewer to the city limits ... the paving of the street [Woodward] between the railway crossing and the city limits ... [and] the extension of the city limits." ("On the co-operative plan." DFP, Sep. 19, 1890.) Rather than preserving the boundaries of his village, Captain Stevens seemed to be far more focused on extending his electrical streetcar franchise into downtown Detroit, eliminating the need for a transfer to Highland Park.

"To extend the city limits offers an easy solution to the rapid transit problem," Alderman John C. Jacob told the Free Press in October 1890. "None of the street railway companies want to adopt rapid transit when their lines extend only three or four miles in any direction. But give them a six, ten or thirteen mile run, and it is to their own interest to cover the distance as quickly as possible." ("May take in the suburbs." DFP, Oct. 15, 1890.) The Free Press concurred in an editorial printed several days later:

There can be nothing more to the advantage of all the owners of this property than to have it included within the limits of the city. The only thing that can possibly make the suburban acreage of anything more than speculative value is rapid transit, and this will be of questionable advantage, unless the city has the power to give franchises for the construction of roads many miles in length and can control the fares charged thereon. The man who would otherwise readily buy a lot at Highland Park, and make his home there, would hesitate to do so if he were to be charged a second fare after passing the present limits of the city...("Bound to come." DFP, Oct. 19, 1890.)

A horse-drawn streetcar on upper Woodward Ave., circa 1880s.

A horse-drawn streetcar on upper Woodward Ave., circa 1880s.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

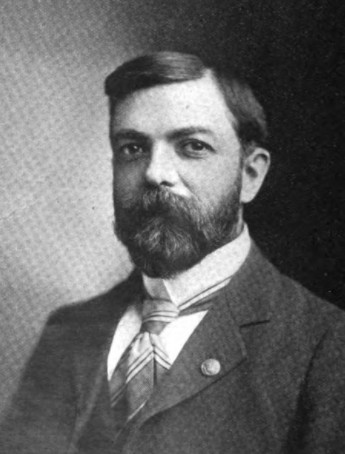

When the North Woodward Avenue Improvement Association was organized, Wilson I. Davenny served as board secretary. Davenny had just quit his job as editor at the Detroit Journal in order to enter into the real estate business. As the organization pursued its various objectives, including extending the city limits, he told a Free Press reporter:

"Petitions for the annexation of this section to the city have been signed almost unanimously by the owners of property in the territory. The petitions in question set forth the willingness of the property owners to assume the obligation of increased taxation in return for an opportunity to participate in municipal public improvements. The signatures to the petitions for the extension of the limits of course include the names of real estate dealers in the section, but they are largely outnumbered by the single lot owners, the major portion of whom expect ultimately to make their homes on the land they have purchased." ("Against the toll road." DFP, Jan. 18, 1891.)

Wilson I. Davenny, Secretary of North Woodward Ave. Improvement Assn.

(Hathi Trust)

State Representative William B. Jackson of Detroit announced in early February 1891 that he would soon introduce the legislation to expand the Detroit city limits. (At the time, only the legislature could alter municipal boundaries.) In addition to the lower Highland Park area, the original annexation bill included large portions of Hamtramck and Springwells townships on either side of the city. On February 6, the Free Press noted:

Mr. Davenny is here [Lansing] in the interest of some Woodward avenue real estate men to procure an enlargement of the city limits of Detroit. ... The following Detroit real estate dealers arrived to-night to further the annexation of a strip of Greenfield and Hamtramck on either side of Woodward avenue: Homer Warren, J. R. McLaughlin, R. Wagner, F. L. Brooks, Charles D. Warner, C. D. Standish, F. W. Claxton, J. W. Bearmont, F. R. Hawley, Clarence Leonard. ("The legislature." DFP, Feb. 6, 1891.)

Representative Jackson officially introduced House Bill 214 on February 12. After weeks of debate and some modifications (including dropping Springwells from the annexation), the House passed the legislation on April 23, followed by the Senate on May 12. By the signature of Governor Edward Winans on the following day, the border of Detroit was moved about one and a half miles north, to the alley between Webb and Tuxedo streets.

The following celebration occurred two weeks later, as reported in the press:

The real estate dealers of Detroit covered themselves all over with glory last evening by the magnitude and richness of the reception they accorded to the Wayne County delegation in the State Legislature at the Hotel Cadillac. The grand dining room of this superb hotel was a picture of fairyland at 9 o'clock when about 120 of the most enterprising, pushing and energetic business men of Detroit sat down to one of the long banqueting boards, made brilliant with roses and maiden hair fern and the air fragrant with the heavy perfume...

With the coffee and confections came the speech-making, much of which was extremely felicitous. W. I. Davenny acted as toastmaster and the following gentlemen responded. Senators Park, of Wayne, and Brown, of Montcalm; Representatives Henze, Marion, Nolan, Holton, McCloy and Jackson. The next speaker was Homer Warren and at the conclusion of his remarks he presented W. I. Davenny, in a very graceful speech, a gold-mounted inkstand on an onyx base with a gold pen, inscribed: "To W. I. Davenny, by the North Woodward Avenue Improvement Association, in recognition of services, May 30, 1891."

("Business men and law makers." DFP, May 31, 1891.)

The northern annexation of 1891—often referred to as the "North Woodward" section— did eventually grow into a high-class residential section stocked with elaborate homes. Today, the area contains the neighborhoods of Boston Edison, Arden Park, Virginia Park, Piety Hill, North End, Historic Atkinson, and Gateway Community. However, actual development was still years away, as the nation entered into a long economic depression following the Panic of 1893.

The Remnant

An odd result of the annexation was that the village lost most of its local government. The village president, three of the six trustees, the clerk, treasurer, assessor and constable all lived on the Detroit side of the border after the change, leaving just three village trustees and the street commissioner in Highland Park. The remainder of the village council called for a special election, and the vacancies were filled. The Detroit & Birmingham Plank Road Company, which was being sued by the Highland Park council to move its toll gate outside the village, made the claim that the village was no longer a legal government after losing so many of its officers, thereby eliminating the suit against the company. However, the Michigan Supreme Court sided with the village, affirming its legal existence.

Real estate in Highland Park and vicinity was fully booming during the 1891 annexation. A businessman named Clarence A. Black purchased 17 acres at the corner of Woodward and Glendale avenues for $30,000 in January 1891, and flipped the property just less than two months later for $35,000—a profit equal to $145,000 in today's dollars. ("Another excellent week." DFP, Mar. 27, 1892.) Hamilton Boulevard, on the village's western border, was extended from Glendale Avenue up to Six Mile Road that year, opening up more land for development. There was already discussion of establishing another electric streetcar down Hamilton. The village council had condemned three lots on Buena Vista Street for a school in October of that year, so that children no longer had to attend class on the second floor of Captain Stevens' waterworks building. The Captain had in fact given up on the idea of supplying the village with groundwater and leased the building to Wilbur W. McAlpine, who began operating a shoe factory there in March 1892, employing 30 workers. (Incidentally, Captain Stevens was an investor in the shoe factory and sat on the company's board of directors.) The new school building, designed by architects Malcomson and Higginbotham, was completed by June 1892.

The Stevens School on Buena Vista Street in 1902.

(freep.newspapers.com)

Students posing at the Stevens School, 1903.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

The Village Annexes

The borders of Highland Park took on the shape they have today as a result of a bill which State Representative Ari E. Woodruff of Wyandotte introduced at a session of the Michigan Legislature on February 18, 1893. Known as House Bill No. 456, it was referred to the House committee on municipal corporations, which recommended the bill's passage on February 28.

Ari E. Woodruff introduced the legislation to expand Highland Park's borders in 1893. (No apparent relation to Fremont Woodruff, Captain Stevens' son-in-law.)

(freep.newspapers.com)

On March 2, Representative Woodruff presented a petition from property owners asking to be included within the village's borders. Later that day, he moved that the House vote on House Bill No. 456, which it passed by 67-0. The Senate's committee on cities and villages also recommended passing the bill, which the Senate did on March 7, by a vote of 25-0. Governor John T. Rich signed it into law the next day.

The legislation—officially Act 264 of 1893—defined the new boundaries of Highland Park as follows. The western border is a line "80 rods" (1,320 feet, or one quarter of a mile) west of and parallel to the east edge of Hamilton Boulevard. The northern border is "the center of the six mile road so called," which is really a US Public Land Survey section line. (I have written about the public land surveys in metropolitan Detroit here.) On the east, the village ends at the western boundary of the right-of-way then owned by the Detroit, Grand Haven and Milwaukee Railway, now used by Canadian National Railway. The southern boundary is the same as Detroit's northern boundary at the time, which is essentially a line running directly through the center of sections 23, 24, 25 and 26 of the Ten Thousand Acre Tract.

Under Michigan law, villages are not completely independent municipalities, but remain part of the townships from which they derive their territory. The township government remained in charge of certain functions within the village, such as collecting taxes and organizing elections. As a village, Highland Park was inseparable from Greenfield and Hamtramck townships.

A Tax Haven?

Captain Stevens was a stockholder and president of the Crescent Transportation Company, whose fleet of steamboats transported goods all across the Great Lakes. The company was originally called Ward's Detroit & Lake Superior Line, but changed its name in 1891, while at the same time changing its address from Detroit to Highland Park. The following year, the company's assets were taxed both by the city, for $1,975 and by the village, for only $495. The $1,480 in annual savings equals about $43,000 in today's dollars.

The SS William H. Stevens, one of Crescent Transportation's package freighters.

(Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library, Great Lakes Maritime Collection)

When Detroit attempted to collect the taxes, Crescent Transportation sued the city, insisting that only Highland Park could tax them. However, the judge in the case found Captain Stevens' company primarily conducted business out of its Detroit office, that most company officers lived in the city, and that Crescent's cash was held in a Detroit bank. Also, company officials openly admitted to moving to Highland Park explicitly to take advantage of the lower taxes. ("Must pay city taxes." DFP, Mar. 18, 1894.)

Suburban Development

The great promise of Highland Park is that it offered "city conveniences without city taxation". Before any development is built, however, three basic requirements must be met: 1) transportation, 2) water, and 3) sewerage. The electric streetcars solved the first problem. Yet providing water and sewerage economically and sustainably is a problem that Highland Park never solved. Founding the village was the easy part—but once people began moving in and demanding the utilities that had become custom to in the city, the village started heading down a path of reckless borrowing that not even Captain Stevens was able to stop.

On the same day that Representative Woodruff introduced his bill to expand the borders of Highland Park (which passed without difficulty), he also sponsored the much more controversial House Bill No. 455, which would empower Highland Park's village council to issue up to $60,000 ($1.8 million today) in municipal bonds for sewer construction. The landlocked suburb was still using the county ditch as its sewer, discharging their raw sewerage into Conners Creek. Detroit had spent an accumulated $300,000 on its Woodward Avenue sewer—which had just been extended through the 1891 annexation area—and Detroiters were indignant at the wealthy, low-tax suburb's sense of entitlement to use city property. When discussing the issue with village representatives in June 1892 (months before the bill was introduced), Detroit Department of Public Works Commissioner James Dean remarked, "I don't believe that I or anyone in Detroit should be taxed to enrich anybody else, and granting this proposition opens the door to others of a like nature." ("Highland Park." DFP, Jun. 7, 1892) Several days after that meeting, an outbreak of typhoid fever in Detroit was blamed on heavy rains and flooding, causing sewerage to back up into people's basements. City Health Officer Dr. Samuel Duffield expressed concerns about Detroit's overburdened sewers which seem almost prophetic today:

"The recent heavy rains ought to be a warning to the city not to allow outside villages to connect with our public sewers. I understand that the officers of Highland Park have made an application in this direction which is now in the hands of the committee on streets. My opinion is that for the safety of the city the outlying villages should not be granted the privileges of the city sewerage, and that they should have sewers of their own. The rapid growth of Detroit has changed matters very materially: the woods outside of the city limits are rapidly disappearing which prevents the absorbing of water, and, as a natural consequence, the water forced through the city sewers is heavier than in former years. The City Engineer should calculate on a greater rain fall than what we have had in making estimates for new sewers so that all the water can be taken care of." ("Contagious diseases in Detroit." DFP, Jun. 12, 1892.)

Sewer pipe awaiting installation on Congress Street, circa 1900.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

The sewer bond bill continued to be debated weeks after the village expansion law passed. One opponent of the proposition was the recently elected Senator Joseph R. McLaughlin, one of the founding members of the North Woodward Avenue Improvement Association. He believed that the village's debt would ultimately become Detroit's problem:

"The bonds will be issued to run thirty years, at a low rate of interest, and that interest is all the people of Highland Park will ever pay. Long before the bonds become due the Village of Highland Park will be annexed to the City of Detroit, and the City of Detroit will have the bonds to pay. Detroit people were taxed $17 on each $1,000 of valuation last year; Highland Park people, $3. Now they propose to construct a sewer, connect it with our Woodward avenue sewer, pay about one-sixth as much taxes as we do, and thirty years hence we will have the privilege of paying for their sewer. It is a scheme that I shall oppose in the Senate." ("The trick of a neighbor." DFP, Mar. 31, 1893.)

Detroit Board of Public Works Commissioners John McVicar and Jacob Guthard expressed similar concerns. ("Think it a real estate scheme." DFP, Mar. 25, 1893.) There was also a fear that the bill would force Detroit to accept a sewer connection against its will, although the bill did not include such language specifically. Captain Stevens asserted that Highland Park would never seek annexation. He pointed out that sewerage in Highland Park was already draining into open ditches, which emptied into Conners Creek, potentially creating a public health hazard. "The trouble with Mr. McLaughlin," said Captain Stevens, "is to be found in the fact that he is interested [invested] largely in subdivided land inside the city limits of Detroit, and is naturally opposed to such facilities being extended to localities outside the city." ("That Highland Park sewer." DFP, Apr. 15, 1893.) Captain Stevens also assured the public that Highland Park's sewers would be built up to the standards and under the supervision of Detroit's Department of Public Works.

Captain Stevens' fieldstone house on Woodward Ave. was a conspicuous addition to the village in 1893, constructed by masons Henry Ivo and Franklin N. Cooper. The McGregor Public Library now stands on this spot. (freep.newspapers.com)

Captain Stevens' fieldstone house on Woodward Ave. was a conspicuous addition to the village in 1893, constructed by masons Henry Ivo and Franklin N. Cooper. The McGregor Public Library now stands on this spot. (freep.newspapers.com)When the bill came up for a vote on the Senate floor on April 18, Senator McLaughlin tried to introduce amendments requiring that the bonds be repaid in ten annual installments, and that Highland Park be prevented from spending the funds before reaching a definite agreement with Detroit on a sewer connection, but the amendments were defeated. McLaughlin expressed his disapproval:

"I earnestly protest against the passage of the bill in its present form, because, first, said Village of Highland Park is not a village in the character of its composition. It is not a compact or homogenous center of population. On the contrary, it has an area of 1,920 acres of land with but sixty-five houses scattered over it, one house to each thirty acres. Second, it is organized as a temporary makeshift with no idea of permanently maintaining its village form of government, but of seeking annexation to the City of Detroit. A village of this character should not be allowed to incur debts without making provision for their payment and especially should it no be permitted to issue long-time bonds intended to outlive it without such provision. I believe it to be the deliberate intention of said village to construct its sewers on a plan which will necessitate connection with the sewers of the City of Detroit and then throw itself upon the generosity of the city in getting permission for making the necessary connections. I believe and charge it to be their purpose to avoid a discussion of this question upon its merits and freed from any embarrassing conditions, but that they propose to complicate the matter by endeavoring to put the city in a position where it would seem ungenerous in refusing, inasmuch as their money was expended and their system would be of no use to them unless they obtained the desired outlet." ("Church taxation." DFP, Apr. 19, 1893)

Besides his successful career as a real estate dealer, State Senator Joseph R. McLaughlin had also organized the Edison Illuminating Company of Detroit and later served as Acting Lieutenant Governor of Michigan.

(Hathi Trust)

Although Highland Park was not ultimately annexed, McLaughlin described exactly what happened with annexations in the 1910s and 1920s: outside villages and townships carelessly issued municipal bonds for expensive schools, sewers, and other improvements, netting big profits for land speculators, after which Detroit was stuck with all the debt. In any case, Captain Stevens' accusation—that McLaughlin opposed the sewer bond bill because he was heavily invested in city property—appears to be true. When McLaughlin was up for reelection in 1894, Mayor Hazen Pingree backed one of McLaughlin's opponents, telling the Free Press:

"[McLaughlin] opposed the bill permitting Highland Park to bond itself for sewers, and when I asked him for his reason he said that he owned some property out Woodward avenue inside the city limits. If Highland Park were sewered people would buy property in the village, and it would hurt his property. I thought that a very peculiar argument." ("Pingree will be in it." DFP, Sep. 11, 1894.)

Joseph R. McLaughlin was part owner of at least these six subdivisions in the North Woodward area, annexed in 1891. They are now part of the Gateway Community, Arden Park, North End, and Piety Hill neighborhoods.

Joseph R. McLaughlin was part owner of at least these six subdivisions in the North Woodward area, annexed in 1891. They are now part of the Gateway Community, Arden Park, North End, and Piety Hill neighborhoods.The bill easily passed, with McLaughlin and Marden Sabin of Centreville casting the only "nay" votes. "There was much rejoicing at Highland Park on Tuesday evening as the result of the passing of the park sewer bond bill," reported the Free Press. "In addition to a large bonfire, there were speeches and songs." ("Sayings and doings." Apr. 20, 1893.) The village council unanimously voted in support of issuing the $60,000 sewer bonds the following month. However, no further action was taken that year, as the village remained preoccupied with fights over street car franchises, complicated by an ongoing legal battle with the toll road company. Captain Stevens scored a major victory that year, when the Detroit Suburban Railway purchased the Highland Park Railway in February. The lines were united, and villagers could now take a single electric train all the way downtown.

Drainage

Dissatisfied with the 1893 council's performance, voters elected all new candidates to village offices in March 1894, in what the Free Press called a "contest waged ... between the friends, so-called, of Highland Park and those who are interested in village real estate," citing the sewer issue as "the one bone of discord." ("Highland Park election." DFP, Mar. 13, 1894.) The new council president, Herman E. Cook, met with Detroit's Board of Public Works the following month to discuss the village's sewer plan. They wanted to build a 1.8-mile sewer down the middle of Woodward and connect it to the northern end of Detroit's sewer at the city limits. Officials were cold to the idea burdening the sewer with drainage from an outside village. They demanded $35,000 just for permission to make the connection. No deal was reached, and the bonds were never issued.

There were plenty of factors complicating the drainage situation between Detroit and Highland Park. There was Palmer Park, recently donated to the city and lying just north of Highland Park, which itself would require a sewer connection. Senator Palmer himself lobbied the Board of Public Works in support of a sewer connection between Detroit and Highland Park to no avail. There was also the issue of the city having recently removed the ditches alongside Woodward Avenue after the 1891 annexation, when the city sewer was extended and the street was paved with asphalt. These ditches had previously emptied into Conners Creek by way of the Holbrook Ditch, draining the part of the village lying south of the "high land" around Glendale Avenue. The city simply did not view this as their problem.

Locations of ditches indicated on old maps dating between 1885-1905.

Locations of ditches indicated on old maps dating between 1885-1905.The village focused on other improvements for the remainder of 1894, including the purchase of a chemical fire engine, establishing a uniform width of 100 feet for Woodward Avenue inside the village limits, and granting a new electric street car franchise on Hamilton Boulevard. Meanwhile, Captain Stevens was negotiating with Detroit to connect the city's water supply to pipes he had already laid.

Up by the Highland Park Hotel, where horse races had been held since at least the 1880s, the newly established Gentlemens Driving Club was at work on constructing a half-mile race track. A grandstand was built the following year. The club later reorganized as the Highland Park Club and expanded the track to one mile in length. The races (and betting) drew thousands to the track every racing season.

The grandstand as it appeared in 1895.

(freep.newspapers.com)

Highland Park Seeks Annexation

Feeling that they had waited long enough for city services, a large number of villagers held a meeting in February 1895 to determine what to do about it. The Free Press claimed it was "the unanimous sentiment that the time had come when the village must have some improvements in the direction of water, electric light and fire protection." And if these couldn't be obtained, then the village should seek annexation to Detroit, which would automatically entitle the territory to all city services. Should annexation fail, they would seek permission from the state to raise $25,000 through issuing municipal bonds. ("May be annexed." Feb. 10, 1895.) A committee of villagers drafted an annexation bill, which Representative Ari Woodruff introduced in the legislature on February 15 as House Bill No. 476. The legislation contemplated taking in not just all of Highland Park, but all of the area north of it up to Eight Mile Road.

The legislature received a petition in protest of the bill, signed by 23 area residents. "The petition states that most of the property proposed to be taken in is farm land, and that if annexed to the city it would increase taxation," according to the Free Press. "It says annexation is favored principally by the real estate dealers, and others whose land is uncultivated." ("Puzzling." DFP, Feb. 28, 1895.) After passing in the House, the Senate received a second petition, signed by 68 citizens of Highland Park, including Captain Stevens. The petitioners pointed out that 90% of the village consisted of open fields and contained fewer than 100 voters. They repeated the assertion that annexation "is desired by a very few real estate speculators whose lands are uncultivated," and that city improvements "are premature and will not be necessary for several years to come." The Senate committee on cities and villages reduced the annexation area slightly in April, eliminating the land east of Oakland Avenue. Ultimately, the committee tabled the bill in May, effectively terminating it.

The only attempt to take on debt to pay for massive improvements that year came when Wilbur McAlpine—the shoe manufacturer, who had become a village trustee—presented a resolution that Highland Park bond itself for $40,000 to pay for a waterworks. But the council unanimously rejected the resolution, and even McAlpine apparently changed his mind on the subject.

By the end of 1895, the village council was meeting in a new hall which Captain Stevens had constructed on Woodward Avenue, known as "Stevens Hall," located where Highland Norge Village Cleaners now stands. The village government had previously conducted business in various places, including several months in a house on Cortland Street, according to one newspaper account. One block to the south, on the other side of Woodward, work was under way on the Highland Park Presbyterian Church, which began as a Sunday school held in the McAlpine shoe factory building. The church was dedicated in January 1896, originally standing at the northwest corner of Woodward and Cortland, but later relocated 300 feet to the north, where it still stands.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

(Google Street View)

The Village Gets City Water

At their first meeting following the March 1896 election, the council appointed committees on sewers, sidewalks, water and light, and adopted a resolution "to present at the next meeting plans for the most expedient means to secure" these benefits. ("Highland Park council." DFP, Mar. 17, 1896.) This resulted in three ballot proposals in May, asking voters to approve issuing $30,000 in bonds (≈$950,000 today) for a waterworks, electric lighting, and a combination village hall and fire station. Although all three proposals passed, the village's biggest taxpayers organized a "landowners committee" in protest, contending that Highland Park's population was below the 500 minimum for taking on that debt. Captain Stevens, William H. Davison, and Arthur G. Tyler obtained an injunction in Wayne County Circuit Court to prevent the village council from issuing the bonds, arguing that a recent village census included horsemen and jockeys staying at the Highland Park Hotel during a racing event.

The Highland Park Club, some time following an 1897 renovation.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Captain Stevens was especially critical of the estimated $23,000 cost for a water supply. He insisted the job could be done for $10,000, based on his own research, having corresponded with 26 cities and villages across Michigan. Claiming that the village only had 420 inhabitants anyway, Captain Stevens asked, "What's the use of this village putting in a system for a city of 5,000 inhabitants?" ("A waste of money." DFP, Jun. 28, 1896.) A Wayne County Circuit judge ultimately dissolved the injunction against the village issuing the bonds, after most of the disputed residents signed affidavits affirming their Highland Park residency.

By December 1896, village officials had signed an agreement with Detroit's Board of Water Commissioners to lay 26,445 feet of water mains in sections of Woodward, Hamilton, Tuxedo, Cortland, Highland, Glendale, Farrand Park, Buena Vista and Gerald. The city also installed water gates and fire hydrants, and was to supply the water, billed at three cents per 1,000 cubic feet. Work commenced before the new year. By January, the Detroit Electric Light & Power Company was installing the first street lights. The village council also revived the sewer issue in early 1897, again placing a sewer bond proposal on the ballot at the upcoming election.

The various buildings of "downtown" Highland Park as depicted in the 1897 Sanborn maps of Detroit.

(loc.gov)

As the village looked forward to the 1897 election, a group calling themselves the Citizens' Improvement Party organized in opposition to the incumbent members of the village government. They produced a list of nominees for all elected positions, including large landowners such as William H. Davison, Arthur G. Tyler and George T. Ford. The Citizens' Improvement Party supported the popular infrastructure improvements going on in the village, but at the same time seemed bitterly opposed to taking on debt or raising taxes to pay for them. ("Politics in the north." DFP, Feb. 21, 1897) The voters elected every single nominee of the Citizens' Improvement Party—while at the same time approving the $60,000 sewer bonding proposal. ("Township elections." DFP, Mar. 9, 1897.)

When the village approached the city to negotiate a sewer connection several months later, Board of Public Works President John McVicar refused, saying that the Woodward Avenue sewer was already at capacity. And even if the sewer could take on all of Highland Park's drainage, then the village should pay at least $5,000 a year for the privilege. "If the Highland Park people do not agree to my terms, I shall offer them the right of way through the city for a sewer to be built by themselves," McVicar said. "I do not think property in the village would be worth much, if incumbered by the amount of bonds such a course would make necessary." ("Must pay $5,000 a year." DFP, Sep. 3, 1897.) The formal written proposition from the city demanded $20,000 cash for the connection in addition to annual payments of $1,500, which the village council rejected. McVicar informed Highland Park that Detroit would build larger sewers in the future, which Highland Park could connect to some day.

There was another short-lived attempt to annex Highland Park in 1897, when Nathaniel McLean Seabrease, a Detroit bond broker, showed up in Lansing in February with a drafted annexation bill. He convinced State Representative William L. January to introduce the legislation after State Senator Arthur L. Holmes refused. However, the bill was killed in committee in April because it was believed to be unconstitutional.

One particularly interesting development seen in Highland Park in 1897 was construction of a bicycle racing track at the northwest corner of Woodward and Monterey. The banked, quarter-mile track had a wood-plank surface and first opened to the public on May 31, 1897. Detroit Cycle Park, as it was first known, also contained a grandstand and bleachers for the crowds who attended competitive racing events.

Bleachers and track at Detroit Cycle Park.

Bleachers and track at Detroit Cycle Park.(Detroit Historical Society)

(freep.newspapers.com)

(freep.newspapers.com)

The "Sewer Party"

At the spring 1898 election, two factions had developed: the Improvement party, and the unfortunately named Sewer party:

The Sewer party is in favor of building a tunnel sewer under Woodward avenue to the city limits and then bringing suit against the city of Detroit to compel it to allow the village the use of its sewers to the river for a moderate rental. They have secured the opinions of able lawyers to the effect that they can force the city to do so. The Improvement party, on the contrary, wants the sewer project shelved until the city has decided to grant the request of the village. The Sewer party also wants to erect a city hall.

("Suburban election." DFP, Mar. 14, 1898.)

The election only resulted in a divided village council. The only opposition candidate to win was Wilbur McAlpine, the new council president. When it came time to actually issue the sewer bonds, McAlpine—along with the reelected clerk, Joseph W. Brinkert—refused to sign them. The village sued the McAlpine and Brinkert, who lost their case, even after appealing it up to the state supreme court. With his hand now forced, McAlpine wrote to the city, again pleading for a sewer connection: "It is a mere question of time when the village of Highland Park will become part of the city of Detroit," he wrote, "and as a natural and common law right the village is entitled to drain its surface water down Woodward avenue." ("Some day." DFP, Jul. 31, 1898.)

The village council quickly accepted contractor James Hanley's $51,850 bid to build the sewer, seemingly indifferent to whether Detroit would allow them to discharge into their system. When excavations began in late August, and Board of Public Works Commissioner Herman F. Kallman was incredulous that the work was allowed. "The area that the Highland Park people propose to drain is 1,800 acres additional, and it would swamp the sewer," he told the Free Press. "If the property was ruined, it would not be Highland Park that would suffer most, but the best down-town districts." ("Highland Park sewer." DFP, Aug. 6, 1898.) Lawyers from both sides were ordered to draw up a preliminary sewer connection agreement, which was delayed as they awaited consultation by the appropriate engineers. Meanwhile, Hanley the sewer contractor worked at a furious pace. After a month of waiting, by which time Hanley's sewer was completed up to just 57 feet from Detroit's end of the sewer, city lawyers obtained a temporary injunction in the county courts to halt any further progress, arguing that Detroit had to protect itself from potentially dangerous sewerage backups. There was also controversy surrounding the amount Hanley was paid—supposedly double what the job should cost—and allegations that bids for the job were not advertised.

"This whole fuss was started by the real estate men having property in the northern part of the city," complained President McAlpine. "We shall go right along with our improvements, and shall win out, in spite of the real estate men." McAlpine was right about real estate dealers in the North Woodward district opposing improvements in the village. McLaughlin Bros., for instance, protested the sewer connection in August, complaining that village real estate would have the same advantages as adjacent city property, while only paying one-fifth of the tax rate. Village trustee Dr. George Andrews apparently agreed, boasting additional improvements to Highland Park, including the paving of Woodward Avenue, would "effectually stop all real estate transfers in the northern part of the city near the village." ("Have a sewer anyway." DFP, Sep. 4, 1898.)

The sewer issue was sowing contention all around, not just between Highland Park and Detroit, but among the villagers as well. As the Free Press described it:

Taken altogether, it is one of the hottest fights that has ever been waged in Detroit's suburbs, and many Detroit people are taking sides as they are heavy owners of Highland Park real estate. One session of the council became so stormy a few weeks ago that men had to separate a trustee and the village clerk when they were about to come to blows, and every meeting of the council is attended by a numerous lobby to watch the proceedings.

("Big cost to village." DFP, Oct. 29, 1898.)

After the courts stopped the work on Highland Park's sewer, Detroit's lawyers next claimed to have no legal authority under state law to make agreements with outside municipalities regarding sewer drainage. Some pointed out that a certain Greenfield Township subdivision under development by Frank J. Hecker was allowed to connect to Detroit's Sixteenth Street sewer. But the city argued back that their agreement was with a private individual who was improving his property without bonded debt, and that the developer fully expected that subdivision—LaSalle Gardens—to become part of the city. In any case, the Board of Public Works refused to consider Highland Park's connection until the matter was decided in court.

Paving Woodward

Ahead of the March 1899 village election, a "Good Government" party organized on the platforms of "value for money expended" and "improvements not dictated by outsiders." ("Village elections in the suburbs." DFP, Mar. 12, 1899.) They accused the incumbent village government—of the Improvement party—of being behind yet another attempt to annex Highland Park to Detroit. (Not just one, but two annexation bills—House Bill 1013 and Senate Bill 341—were introduced in February, but neither progressed far.) The Improvement party was running on its record of infrastructure upgrades, and paving Woodward Avenue was the next big project. In order to make this happen, State Representative Solon Goodell introduced legislation on February 8 allowing villages to pay for paving projects over a period of five years rather than all at once, and issue bonds up to four years paying 6% interest. In a what was effectively a mandate from voters in favor of the continued spending, the Improvement party swept the village election. Council members openly supported the paving bill, while major landowners from the Good Government party—including Captain Stevens, William Davison, and Arthur Tyler—lobbied against it. The bill passed in April, and the paving of Woodward Avenue began that August. Street car tracks were moved to the center of the road, and the asphalt pavement was laid on either side. In coordination with this project, Greenfield Township announced that it would pave Woodward Avenue between Six Mile and Eight Mile roads with macadam. The Free Press declared that this would make Woodward "one of the most magnificent driveways in the world, extending from the river eight miles to the north and including in its course the charms of city, village and country scenes." ("Improve Woodward avenue." DFP, Aug. 6, 1899.)

Woodward and Victor avenues, facing south, 1909.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Highland Park secured another victory that summer, when the injunction against sewer contractor Hanley was dissolved. The court ruled on June 28 that blocking sewer access posed too great a threat to human health, and that the village's natural drainage was partially blocked off by development on Detroit's side of the border. The judge ordered a sewer gate to be installed at the border, which Detroit could close with court permission, and Highland Park was ordered to make annual payments of $500 (≈$15,000 today) for sewer access. But the village had an ace up its sleeve—the new sewer at the city's Palmer Park needed an outlet, and Highland Park offered to let the the park drain into the upper end of its sewer in exchange for the city cancelling the $500 payments. The issue was again brought to court, where the Circuit Court judge ultimately approved of this new deal on December 29.

By the close of 1899, Highland Park had a functional sewer, electric lights, city water, gas pipes, and a newly paved Woodward Avenue. Stevens Hall had been remodeled into a makeshift fire station. The plank road company agreed to move its obnoxious toll gate farther up Woodward Avenue in exchange for $5,000 (to be paid in installments, with interest). Not only could villagers take an electric streetcar downtown—they now had access to interurban cars going as far as Pontiac and Rochester. Highland Park was also beginning to see the construction of higher-class homes around this time. Prominent Detroit architect Almon C. Varney designed a house for John Langdon, an English-born farmer, across Woodward from the Highland Park Hotel in 1899. Frank Weisgerber, owner of the Central Paint and Glass Company, hired Charles W. Koehler to plan a residence at 44 Grand Avenue in 1900. Architect Samuel C. Falkinburg designed multiple homes around this time, including a notable cobblestone house for village president Wilbur McAlpine on Grand Avenue.

Wilbur McAlpine residence, constructed in 1900.

Wilbur McAlpine residence, constructed in 1900.(Google Street View)

The New Century

The "Improvement party" incumbents on the village council were reelected in March 1900, despite opposition from a group of villagers who caucused as the "Reform" party. The Free Press characterized the results of that election:

[T]he people intend to continue the system of public improvements already inaugurated. Under present arrangements it costs no more to ride from the city hall to the northern limits of Highland Park than to ride one block in the city. It is confidently expected by those interested in that suburb, that these improved conditions will induce many homeseekers to pass by the higher priced properties of the city and secure homes in Highland Park village. ("Real estate field." DFP, Mar. 18, 1900.)

All of the shiny new upgrades in Highland Park were attracting a lot of attention in the local real estate market. In early May, the Free Press wrote:

Ever since the new asphalt pavement was completed out North Woodward avenue the inquiry for real estate in Highland Park and vicinity has been increasing. More property has been sold in this part of the city since March 1, 1900, than had changed hands before since the panic of 1893. The public begin to appreciate the advantages this section of the city has to offer now that the fine street car service makes it possible for the business man to reach his down-town office in 25 minutes. ("In the real estate field." DFP, May 6, 1900.)

One well publicized development in the village this year was the Park View Subdivision, lying on the north side of Glendale Avenue. The original developers of this subdivision, Bamlet & Miller, were among the few large landholders on Woodward Avenue who supported the paving of the road the previous year ("Tempest tossed village." DFP, Mar. 27, 1899.), but selling out their land freed them from any taxes and debt associated with the project. Advertisements for Park View highlighted its location on the newly paved Woodward Avenue, calling it "the finest driveway and bicycle road in the world." In addition to paying only one-third the tax rate of Detroiters, residents of the subdivision could also expect:

city and country luxuries combined, a beautiful park at your door, broad boulevards and asphalt pavement for drives and cycling, balmy breezes in summer, away from the noise and dust of the city, a place to rest, to think, to meditate, to grow young. (Advertisement, Detroit Free Press, May 6, 1900.)

After a successful auction sale of Park View lots, one unnamed real estate dealer excitedly told the Free Press, "the men who bought that Woodward avenue frontage will have a chance to double their money in less than three years." ("Real estate market." DFP, May 13, 1900.)

A front-page advertisement for the Park View Subdivision, May 10, 1900. (freep.newspapers.com)

A front-page advertisement for the Park View Subdivision, May 10, 1900. (freep.newspapers.com)Maintaining Highland Park's low tax rate was expensive. The village council called a special election on April 19 for voters to approve an additional $23,000 bond issue for extensions to the water mains and street lights. A majority of voters approved them, but not the two-thirds required to pass. Village trustee Dr. George Andrews feared that this would lead to raising the overall village taxes by $5,000 per year if they were still to attempt these extensions. ("No bonds." DFP, Apr. 20, 1900.) Several months later the village council was discussing cutting the salaries of the clerk and treasurer in half, and the possibility of eliminating some positions in the government. ("Wave of economy at Highland Park." DFP, Sep. 9, 1900.) By the end of the year, the council was attempting to sell the chemical fire engine, which apparently never worked properly. (The only fire protection came from Detroit's Mott Avenue fire station, which the village was allowed to call if the engine was available.) There was no police protection in the village besides a night watchman, while Detroit police officers patrolled Palmer Park and provided security during major races at the Highland Park Club.

The US Census of 1900 found exactly 427 people living within the limits of Highland Park. Incidentally, the supervisor of the census in Michigan's first district, a Detroit lawyer named Flavius L. Brooke, expressed an opinion regarding the city's growing suburbs:

"It is a shame that so many citizens have taken up their abodes in the resorts and townships just without the city limits. They have about all the benefits of the city, but do not share in the cost of maintaining it. If I had my way a delegation would go to Lansing next winter and see that a law was passed incorporating into the city of Detroit all the outlying towns, villages and townships, which would include Highland Park, Woodmere, Delray, Grosse Pointe and slices off of each of the contiguous townships. I hold that all property adjacent to a city that has a value greater than that which it may have for truck farming purposes secures that value for the sole reason that it is adjacent to the city. It should therefore be made to stand for its proportion of the cost of maintaining the city." ("Detroit probably the thirteenth." DFP, Aug. 5, 1900.)

Later that year, the Free Press claimed that several (unnamed) members of the village council were "openly in favor" of annexation, "as it is realized that Highland Park has big sewer and paving debts to pay and would be glad to turn them over to the city." ("Want to be city people." DFP, Nov. 20, 1900.) In January 1901, "Highland Park officials" circulated petitions both for and against annexation "to get the sentiment of the people." ("Suburban." DFP, Jan. 24, 1901.) The majority presumably opposed annexation, as the paper doesn't mention this petition again.

The 1901 Election

At a celebration on February 27, 1901, Detroit Mayor William C. Maybury ceremoniously operated the first street car to pass beneath the Grand Trunk Railroad tracks south of Baltimore Street. The new viaduct replaced an at-grade railroad crossing that was not only very dangerous, but also delayed traffic and generally slowed the city's northward growth. The increased safety and efficiency of Woodard Avenue was about to be a boon for Highland Park real estate, and more changes were on their way.

A vehicle on Woodward approaches the newly completed grade separation at the Grand Trunk Railroad, two miles south of Highland Park, circa 1902.

(freep.newspapers.com)

The grade separation today.

The village council pitched another bonding proposal at the March 1901 election in order to borrow $10,921.50 for water main extensions in Oakland, Woodward, Stevens, Grand, Monterey and McLean streets. Additionally, Representative Frederick C. Martindale of Detroit was in Lansing that February, introducing several bills allowing Highland Park to borrow even more: House Bill No. 446, to authorize the Highland Park school board to borrow $6,000 in order to pay off a previous $6,000 loan; House Bill No. 572, to legalize and validate a controversial sewer tax levy in two Highland Park special assessment districts; and House Bill No. 573, authorizing Highland Park to assess property for more than 5% of its taxable value (the legal limit) for building sewers and drains, and to pay for the assessments by issuing bonds.

The faction of villagers who were opposed to the spending habits of the "Improvement" party then in power had again organized as the "Citizens' Improvement" party. However, they lost one of their largest supporters just five days before the election, when Captain Stevens died from a severe case of pneumonia on the evening of March 6, 1901, at the age of 80. A Free Press obituary remembered him as a "bank president and capitalist (who) wore cowhide boots and coon skin caps to directors' meetings."

Capt. Stevens' fortune is not known, yet it is certain that it runs into the millions... His holdings in real estate amount to more than half a million dollars, most of which is in Highland Park. He owned more than half the village and for years was its political dictator...

Personally, he was blunt in manner, but under the rough exterior there was a kindly and generous nature that prompted him to do many acts of kindness. Only a sturdy physical and mental constitution could have withstood the hardships that Capt. Stevens passed through.

(freep.newspapers.com)

Captain Stevens' funeral was held on Friday, March 8, which was followed by a tribute at the Highland Park Hotel the next day. On the morning of Sunday, March 10, the day before the election, a circular published by his Citizens' Improvement party appeared on the front doorstep of every house in the village, detailing accusations against the incumbent village council. The circular pointed out that overall village taxes were raised from $7,725 in 1899 to $23,400 in 1901, of which the treasurer had only collected $9,000. The high cost of the sewer and paving projects was brought up, as well as the exorbitant inspection fees charged by the contractor. Records showed expenses being paid for the fire department, although Detroit was still providing this service. The circular alleged that village officials held secret sessions, kept irregular records, and paid a lobbyist to support the current bonding bills being debated in Lansing.

The Improvement party complained about the timing of the circular being distributed the day before the election, but the Citizens' Improvement party said it wasn't issued sooner out of respect for Captain Stevens. ("Politicians' last hours." DFP, Mar. 10, 1901.) However, the Improvement party managed to print a circular in its defense by the following day. It responded that tripling taxes within two years was necessary, as the Free Press paraphrased it, "to pay interest on the bonded indebtedness, and maintain the improvements which have changed the village from a farming neighborhood to an up-to-date civic community." ("Improvement circular out." DFP, Mar. 11, 1901.) The Improvement party stood by its record of infrastructure spending, pointing out that the work was well done, that costs were slightly cheaper than in the city, and that the council managed to get out of paying an annual sewer fee to Detroit. The unpaid taxes, they alleged, were mostly owed by prominent members of the Citizens' party. Ultimately, the candidates of the Citizens' Improvement party won every office on the election of March 11, and no new bonds were approved. The Improvement party's nominee for clerk, former village president James F. Hickey, lost to Royal Milton Ford, a 22-year-old grandson of one of the first white settlers in the area. Ford would serve in that position for 16 years until Highland Park incorporated as a city, after which he was elected as the first mayor.

Subdivisions in Highland Park (1904).

Subdivisions in Highland Park (1904).(University of Michigan)

The Post-Stevens Years

At a meeting of the new council held the week following the election, the village was found to be "bankrupt" and that some of its financial records were in disorder. ("Highland Park books in bad condition." DFP, Mar. 20, 1901.) The following month, the Free Press editorialized:

Citizens having business with Highland Park as a municipality did not require the confirmatory evidence of an expert accountant to know that affairs are flying at loose ends in that village. At one time and another it has been the victim of real estate sharks, corrupt officials and a local Tammany in the matter of "grafting" from contractors and [streetcar] franchise seekers. Now the alien property holder is lucky if he can find his land there, and is left to discover for himself whether improvements assessed against him without having been brought to his knowledge, actually exist or not... There have been some excellent individual officials, but the commercial element in politics has had its way too long. (Editorial. Detroit Free Press, Apr. 18, 1901.)

The new council succeeded in lowering total village taxes from $23,400 to $14,208 their first year, but Highland Park was going to have to continue borrowing money in order to continue the improvements that everyone had gotten used to. In April, a divided council voted to spend $50 to lobby in support of one of the state bills being debated at the time, which was to allow Highland Park to take on more bonded debt. A special election was announced in August, for the issue of $10,000 in bonds to pay for improvements, and to pay down other debt. ("Suburban brevities." DFP, Aug. 8, 1901.)

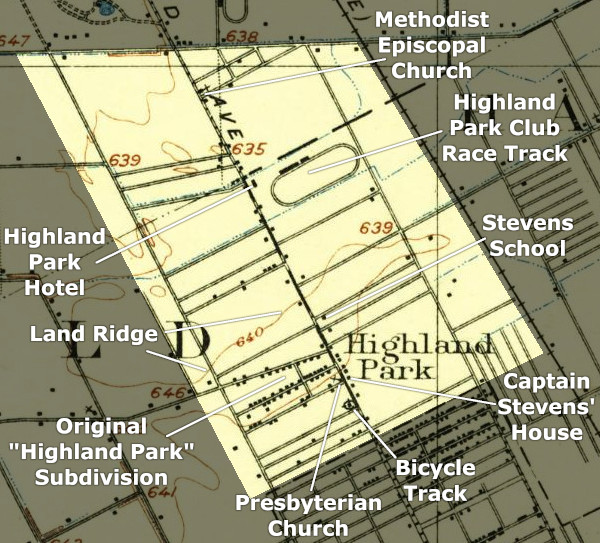

This 1905 USGS topographic map of Highland Park shows that most building activity was limited to Woodward Ave. and the first subdivision by this time.

This 1905 USGS topographic map of Highland Park shows that most building activity was limited to Woodward Ave. and the first subdivision by this time.(USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer)