"The Woodward Plan" by Kati Belz.

"An Adjustment of Titles"

Governor William Hull and Justice Augustus Woodward left Detroit for Washington in October 1805, seeking approval from Congress for their plan to lay out a new town. They issued a report on the situation in Detroit to President Thomas Jefferson, who delivered it to Congress himself on December 23. Hull and Woodward evidently showed Jefferson the new plan of Detroit, actualized by surveyor Thomas Smith. According to Smith, the plan met Jefferson's personal approval.

Thanks to Woodward's lobbying, Congress passed "An act to provide for the adjustment of titles of land in the town of Detroit and Territory of Michigan, and for other purposes" on April 21, 1806. This law authorized the territorial government to:

- Establish a new plan for Detroit, including not just the incorporated town, but also 10,000 acres of adjacent federal land.

- Grant up to 5,000 square feet of property on the new plan to every U.S. citizen over the age of seventeen who lived in the Town of Detroit on the day of the fire.

- Sell the remainder of the land to fund the construction of a courthouse and jail.

Hull returned to Detroit June 7, 1806, followed by Woodward and John Griffin, a new judge appointed by Jefferson to fill a vacancy on the court. Justice Frederick Bates had remained in Detroit. The reassembled governor and judges were ready enact legislation under the new powers granted to them by Congress.

"The Bases of the Town"

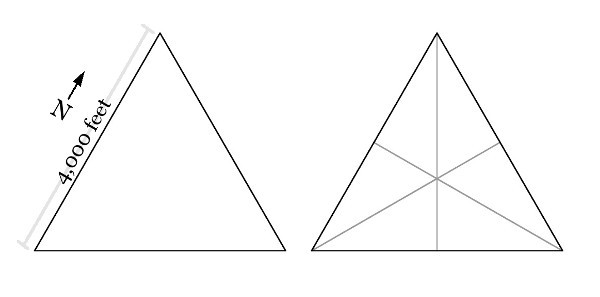

On September 13, 1806 the governor and judges passed "An Act concerning the town of Detroit," which codified the Woodward Plan, more formally known as the Governor and Judges Plan:

The bases of the town of Detroit shall be an equilateral triangle, having each side of the length of four thousand feet, and having every angle bisected by a perpendicular line upon the opposite side...

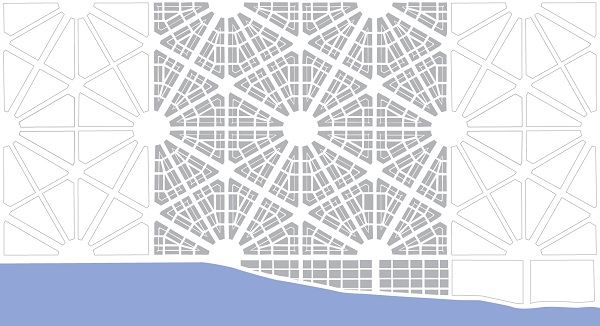

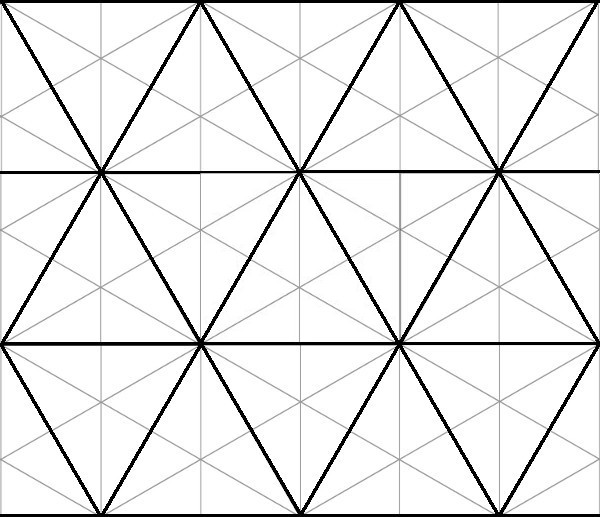

As the settlement grew beyond the confines of the first 4,000-foot triangle, all that town planners had to do was simply add more triangles. This was the main point of the plan--it wasn't simply a decorative arrangement of streets, but a system designed to accommodate growth indefinitely and in an orderly fashion.

Exempted from this pattern were areas close to the Detroit River or where "other unavoidable circumstances may require partial deviation," according to the law. Due to this exemption, the area south of present-day Jefferson Avenue was divided into ordinary rectangular blocks.

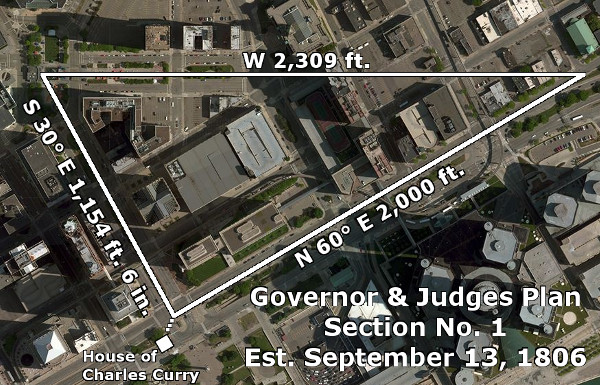

The six segments into which each 4,000-foot triangle was divided were simply called "sections." This legislation defined the boundaries of Section 1, beginning at the intersection of Woodward and Jefferson Avenues:

The town shall commence at a stake, distant eighty-four feet ten inches and one fourth of an inch, from the most northern and western corner of the house of Charles Curry, and shall run thence on the course north, sixty degrees east, two thousand feet; thence on a course due west two thousand three hundred nine feet, thence on the course south, thirty degrees east, one thousand one hundred fifty-four feet and six inches, to the beginning ; with such public squares, or spaces of ground, and such avenues, streets, and lanes, as may from time to time be directed by competent authority. The said figure shall be denominated a section, and shall be numbered section one...

There was nothing special about the house of Charles Curry other than it happened to be the first building standing at the corner of Woodward and Jefferson Avenues. Also, the governor and judges' calculations for Section 1 are slightly off. The approximate lengths of the sides should be, counterclockwise from the bottom: 2,000 feet; 2,309 feet, 4.81 inches; and 1,154 feet, 8.41 inches.

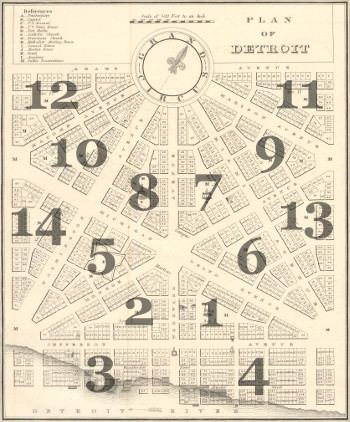

More sections were added, each receiving its number by the order in which they were surveyed. The known numbered sections are as follows:

On the same day that the law codifying the Woodward Plan was enacted, the governor and judges passed "An Act concerning the city of Detroit," which stated that the land "laid off, surveyed and numbered" under the preceding law "shall be a city." The Town of Detroit was now the City of Detroit. (Detroit's status would waver between town and city a few more times until its final incorporation in 1824.)

Anatomy of a Section

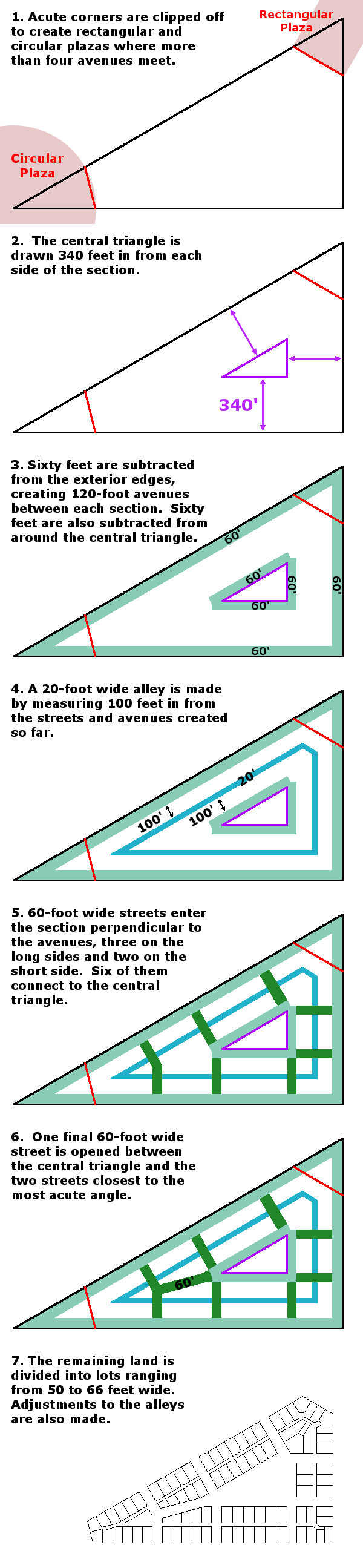

There is no one "true" version of the Woodward Plan. In fact, disparity among the work of several surveyors (often a result of Woodward's own meddling) created a significant amount of confusion that took years to resolve. Yet some principles have remained constant. Woodward described his plan as having been laid out

with squares, circuses, and other open spaces of ground where six avenues, and where twelve avenues intersect; with all the six sections comprising the triangle uniformly and regularly divided into lots of about five thousand square feet; with an alley or lane coming to the rear of every lot; with subordinate streets of about sixty feet width; with a fine internal space of ground for education and other purposes, with...avenues of one hundred and twenty feet width..."The broad thoroughfare running along the border of each section was called an avenue. Where twelve avenues came together, a large circular plaza was created (e.g. Grand Circus Park). Six avenues coming together created a smaller rectangular plaza (e.g. Campus Martius). These open spaces were made by clipping off the acute angles of each section, preventing a multitude of narrow and undevelopable lots. There was also a triangular public space reserved at the center of each section. Legislation passed in 1807 directed that this area should be reserved for open spaces or public institutions, such as markets, churches, schools, fire stations, and other government buildings. This law also mandated ten-foot sidewalks and set strict, detailed standards for the planting of street trees--city planning concepts that would meet the approval of New Urbanists of the twenty-first-century.

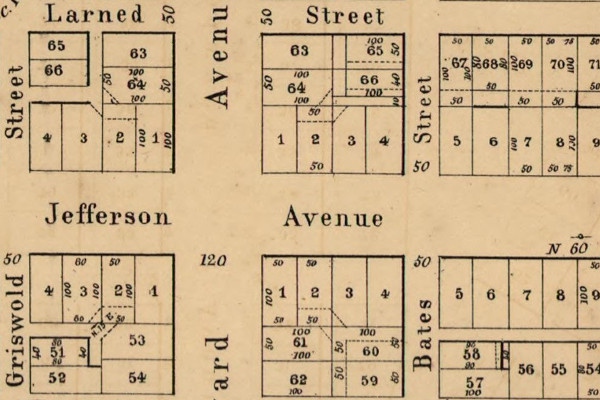

What follows is a breakdown of how a "section" in the Woodward Plan, once outlined, was generally subdivided. Some details differed between the several versions of the plan, such as the widths of the lots and the exact placements of side streets.

The sections closest to the river were mostly subdivided into lots measuring fifty feet wide by 100 feet deep, because 5,000 square feet was the maximum allowance to be granted according to the 1806 act of Congress. Farther away from the river, the standard rectangular lot was about sixty feet wide, but would vary greatly in width in order to maintain regularity in the street network. Odd widths of 61 feet, 65.65 feet, 62.046 feet, etc. can be seen.

Place Names

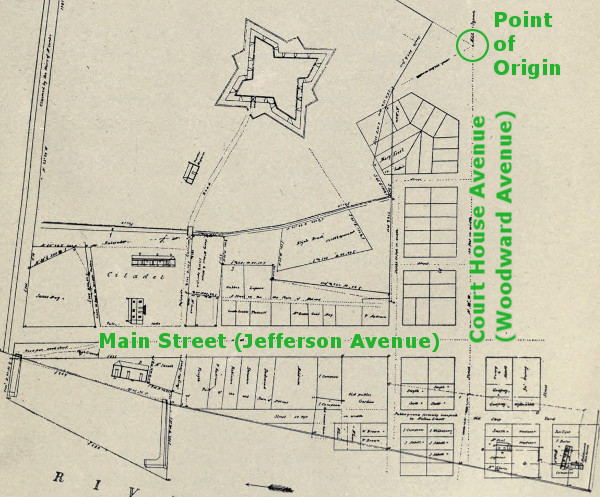

The governor and judges originally envisioned the court house for the Supreme Court of Michigan located at the center of the grand circular plaza now referred to as Grand Circus Park. Such a mandate was included in the 1806 law codifying the Woodward Plan, and early documents refer to this area as the Court House Circus. The road leading from the river to the Court House Circus was called Court House Avenue. This road was of course renamed Woodward Avenue, probably around the time an 1815 law repealed the directive to locate a court house in the Grand Circus.

The rectangular plaza where the Point of Origin was set was called the Military Square because it was adjacent to the Military Reserve. The square was renamed Campus Martius, perhaps in imitation of Marietta, Ohio (once the capital of the Northwest Territory) or of ancient Rome, both of which had public squares with the same name.

In some early records, Michigan Avenue was originally referred to as West Street because it ran west out of Campus Martius. Cadillac Square used to be East Street. The center of commercial activity was Main Street, later renamed for Woodward's idol, Thomas Jefferson.

Abijah Hull

The governor and judges created the office of Surveyor of Michigan by a law passed on September 14, 1806. One of the chief duties of this official was to "lay out, survey, mete and bound the Town of Detroit...and all lands, lots, sections, avenues, streets, lanes, squares, and public spaces of ground within the same."

One month later, the governor and judges selected Abijah Hull, a cousin of Governor William Hull, to fill the position. This was much to the chagrin of Stanley Griswold and James Abbott, commissioners of the Detroit Land Office who had favored Aaron Greeley for the job. Griswold, Abbott, and Greeley--together with John Gentle, the British Detroiter who publicly mocked Woodward's Plan--comprised a faction against Governor Hull and his allies. Surveyor James McCloskey claimed that these men were "Constant associates ... frequently seen ... walking the Streets of Detroit together by night." Griswold was Secretary of the Territory, a position he hated, and he conspired to overthrow Governor Hull and take his place.

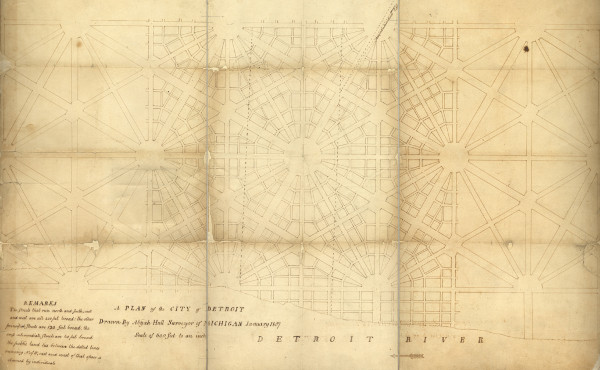

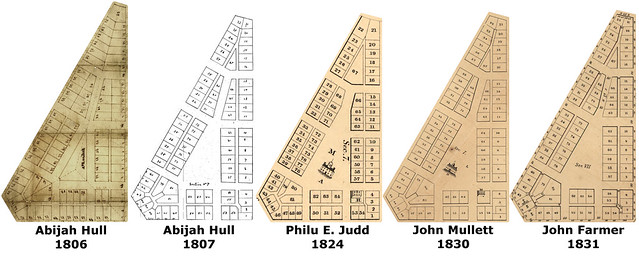

Within several weeks of his appointment, Abijah Hull completed a new draft of the Woodward Plan. The governor and judges sent it to Congress with a letter dated December 12, 1806, stating, "We have the honor to report ... that we have laid out a town or city, of which a plan accompanies this report, and have made progress in the adjustment of titles and the distribution of the donations ... and expect shortly to complete the same." Hull's drawing is the oldest surviving rendition of the Plan of Detroit.

Abijah Hall, "A Plan of the City of Detroit," (1807).

Image courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. (Source.)

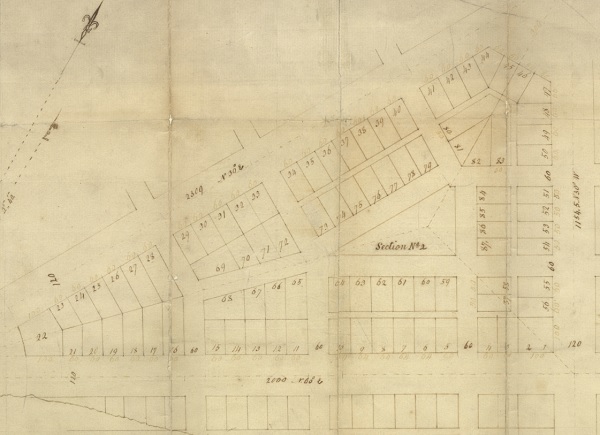

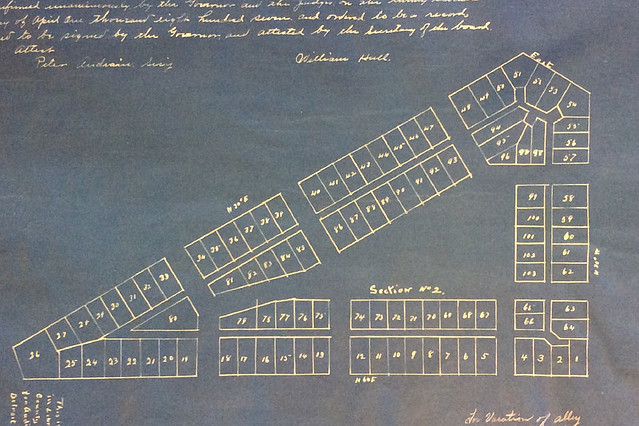

Section No. 2 of the Governor & Judges Plan of Detroit, early version.

Abijah Hall, "A Plan of One Section of Detroit," (1807).

Image courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. (Source.)

Notice that the lots on the left hand side of the lower image do not have rear alleys. This is the only known version of the plan with this omission. The circular plaza at the bottom left is also smaller than subsequent versions, having a radius of only 400 feet rather than 500 feet.

The most significant aspect of Abijah Hull's plan is the variation in the widths of avenues. Apparently, in Thomas Smith's version, all avenues were a uniform 120 feet wide. But by this point, Woodward had instructed Abijah Hull to broaden the avenues that ran north-south or east-west to an extremely generous width of 200 feet. These were referred to as "grand avenues." Smith objected to this change, saying, "The Plan is practicable but it will not admit Innovation without destroying its mathematical beauty and symmetry, and therefore, I was always adverse to the 200 foot streets."

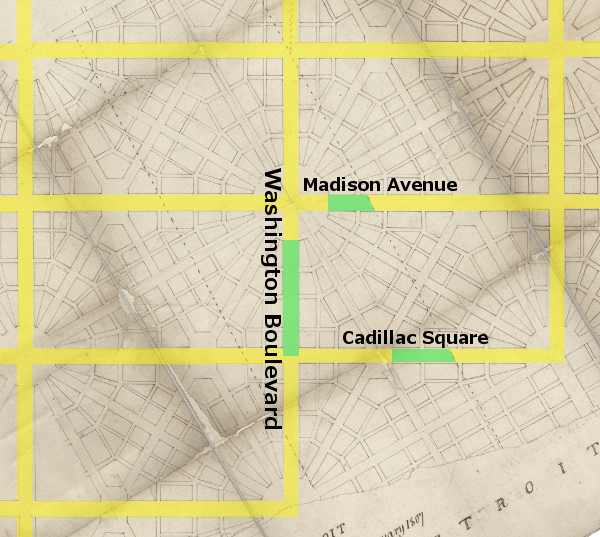

Perhaps Smith never fully appreciated Woodward's grand design, which is easier to see when Abijah Hull's diagram is oriented to true north and the 200-foot grand avenues are highlighted. This creates a grid of rectangular areas each containing 159.05 acres--almost exactly one quarter of a square mile. Had Woodward's plan been fully carried out, this grid would have grounded an otherwise intimidating web of diagonal thoroughfares within a recognizable and familiar framework. Only a few small segments of Woodward's grand avenues were ever built: Washington Boulevard, Madison Avenue, and Cadillac Square. Michigan Avenue runs due west from Campus Martius, but it is only the north half of a grand avenue.

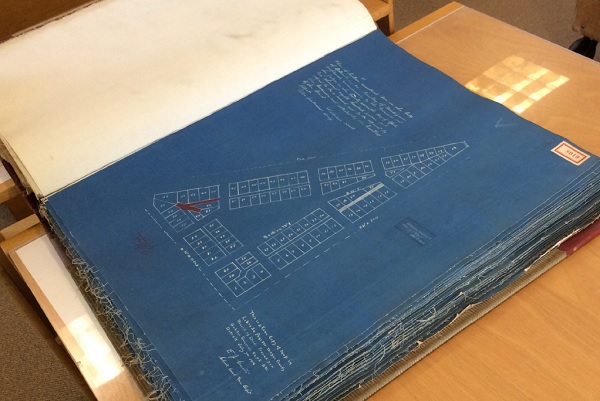

Abijah Hull and Woodward continued to tinker with the plan, eventually producing plats of the first twelve sections of the city, approved by the governor and judges between April 7-27, 1807. In this incarnation, every lot has alley access. Section 2 of this version is below.

Courtesy of the Archives of Michigan.

This is more or less the plan that was finally implemented. On December 12, 1848 the Detroit City Council ordered that copies of Hull's 1807 plan be recorded by the Wayne County Register as a subdivision plat. Sections 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8 were recorded in liber 34, pages 543-550 in the county's book of plats on December 23, 1848. Sections 5, 9, 10, 11, and 12 were recorded on pages 551-555 of the same book on May 30, 1849. Cyanotypes of these pages were made July 6-10, 1916 for the State of Michigan, and can now be found in the Record of County Plats in the Archives of Michigan, volume 118, plat 8019. An online version is available here. Sections 13 and 14 were not recorded, and may never have been fully surveyed. They appear only on Philus E. Judd's famous "Plan of Detroit," drawn in 1824.

The new alley recesses seen in Hull's 1807 plan were criticized by Smith, who called this "theoretical improvement" a "deformity and a nuisance" to his original plan. He also believed that no churches, schools, or other buildings should be constructed in the center of the sections. In an 1831 letter to John R. Williams, he wrote that originally, these spaces "were for gardens and gravel walks, places of deposit in the event of fires and circulation of air," but that Woodward "caused (them) to be filled up with lots ... and obliged subsequent Surveyors to perform his whimsical schemes.... The Plan in its original form drew the attention of scientific persons, and from its novelty, it is to be regretted it was not continued."

"The Satisfaction Due to a Gentleman"

In addition to surveying the city, Abijah Hull was also supposed to mete and bound the private land claims around Detroit, a necessary step in confirming the new government's recognition of their ownership. On August 1, 1807, commissioners of the Detroit Land Office--Stanley Griswold, James Abbott, and Peter Audrain--wrote to the Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin to complain that Abijah Hull had not surveyed a single land claim because he was too busy laying out the new City of Detroit. Word of this complaint got back to Hull, who alleged that he had asked the commissioners for instructions and for the names of the farmers whose land was to be surveyed on multiple occasions, but was ignored.

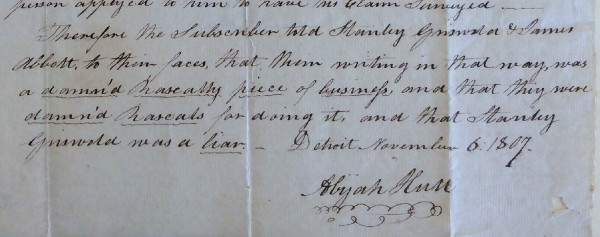

Hull confronted the commissioners on at least three occasions, demanding to see a copy of the letter they sent to Gallatin. At one point he was promised a copy, but the commissioners later changed their minds. Hull furiously drew up a public denunciation of Griswold and Abbott and nailed it up at some conspicuous location in the city on November 6, 1807. "To act openly and expose villains is the duty of every honest man," it began, "for the roguery of Rogues ought ever to be made public." Hull went on to explain all that had happened up until that point, and closed with the following remarks:

"Therefore the subscriber [Hull] told Stanly Griswold and James Abbott to their faces, that their writing in that way was a damm'd rascally piece of business, and that they were damm'd Rascals for doing it, and that Stanly Griswold was a liar."

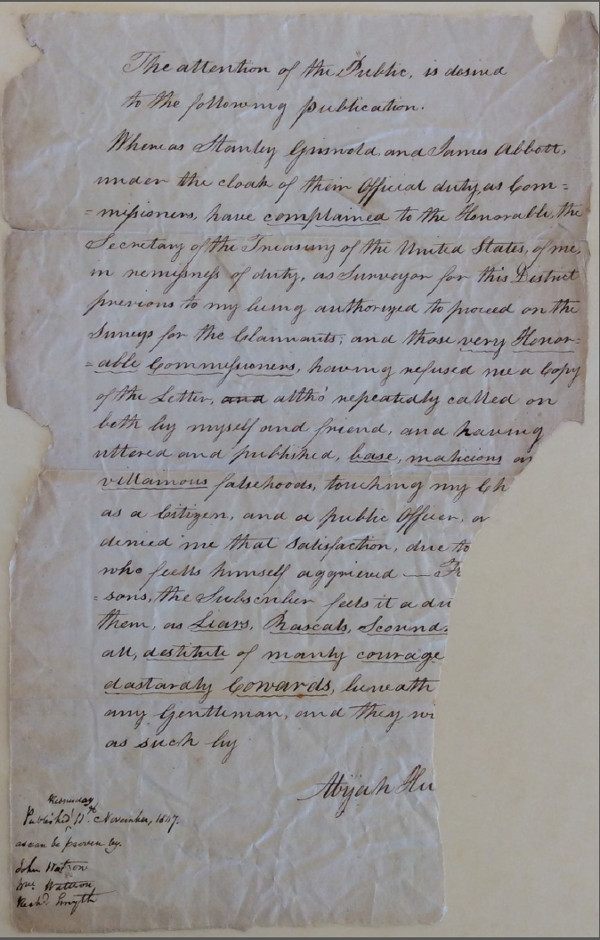

Detail from Abijah Hull's notice posted November 6, 1807.

Courtesy of the Archives of Michigan.

James Abbott shot back with his own public notice:

In a scurrilous piece published this day by Abijah Hull relative to Stanly Griswold Esq. and myself, I observe several falsehoods, consequently think it necessary to inform the public that the said Abijah Hull is not only a liar, but a Perjured Villain and as such he will be treated byWith his mind already agitated by the hours of trigonometric calculations demanded by the Woodward Plan, Hull snapped. The following day, he challenged Stanley Griswold, the Secretary of the Territory of Michigan, to a duel via the following note:

James Abbott.

Stanley Griswold, Esq.:La Petite Côte--the "Little Coast"--was in present-day Windsor, Ontario, about three miles downstream from Detroit. Griswold never showed up, prompting Hull to address the other land commissioner who had so gravely insulted him:

Sir--For reasons which must readily suggest themselves to you, I request that you will meet me as a gentleman this afternoon, at 4 of the clock, below the windmill at the Petite Cote, on the Canada side.

Abijah Hull.

James Abbott, Esq.:Abbott, too, failed to meet his challenger. Hull was reportedly arrested for this behavior, but then bailed out by Elijah Brush.

Sir--The language which you used respecting me in your publication of Saturday last imperiously demands satisfaction. As I conceive that no legal redress can give adequate compensation to injured character and insulted honor, I shall expect you to give me the satisfaction due to a gentleman by meeting me at 11 o'clock tomorrow morning at the windmill on the Petite Cote, on the other side of the Detroit river.

Abijah Hull.

Not ready to give up, Abijah Hull publicly posted a final notice on November 11, 1807. A surviving but badly torn copy reads:

Whereas Stanly Griswold, and James Abbott, under the cloak of their official duty as Commissioners, have complained to the Honorable, the Secretary of the Treasury of the United States, of me, in remissness of duty, as Surveyor for this District previous to my being authorized to proceed on the Surveys for the Claimants; and those very Honorable commissioners, having refused me a copy of the letter, altho' repeatedly called on both by myself and a friend, and having uttered and published base, malicious and villainous falsehoods, touching my Cha[racter] as a Citizen and a public officer, and [having] denied me that satisfaction due to [one] who feels himself aggrieved—— For [these rea]sons, the Subscriber feels it a du[ty to brand] them as Liars, Rascals, Scoundrels [who are] all destitute of manly courage, dastardly Cowards, beneath [the notice of] any Gentleman, and they will [be treated] as such by

Abijah Hull

Abijah Hull's notice published November 11, 1807.

Courtesy of the Archives of Michigan.

The Aaron Greeley Affair

Griswold and Abbott wrote to the U.S. Surveyor General Jared Mansfield and his superior, Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, asking them to remove Abijah Hull and appoint Greeley in his place. Meanwhile, Griswold sent Greeley to Washington, D.C. to deliver a petition for the removal of Governor Hull and Justice Woodward. Gallatin acknowledged that the territory needed a surveyor who would "act in concert" with the land commissioners, but rather than remove Abijah Hull, Mansfield made Greeley an additional deputy surveyor in January 1808. Greeley, however, would not return to Michigan until the following May.

The troubles with Griswold finally ended when Thomas Jefferson removed him from office in March 1808. Still, Abijah Hull told Mansfield that he and McCloskey were only ready to continue surveying "provided we have nothing to do with Greely in the business." Mansfield declined to remove Greeley, simply making McCloskey yet another deputy surveyor that April. Hull complained to Mansfield again in May: "Since you informed me that Mr Greely was appointed to Survey the Claims I have declined acting altogether." Abijah Hull ultimately resigned on August 2, 1808.

Perhaps doubting McCloskey's abilities to continue work on the Woodward Plan, Governor Hull asked Thomas Smith to return to Detroit in October 1808, but Smith declined. McCloskey worked mostly in the city and in surveying a road to Ohio, while Greeley chiefly focused on the private claims. Greeley did however draw up his own rendition of the city plan, but it has not survived.

The subtle but important differences between versions of the plan become apparent in a side-by-side comparison of a sample section.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FULL SIZED VERSION OF THIS IMAGE.

The McCloskey Plan

In late 1808 and early 1809, Woodward was away in Washington, D.C. In his absence, McCloskey proposed that the Woodward Plan be abandoned. At a meeting of the governor and judges on November 21, 1808, McCloskey presented a sketch of an entirely new street layout in an ordinary gridiron pattern. Governor Hull liked the idea and proposed that a full and proper plan be drawn up. The motion passed, with Justice James Witherell voting for and and Justice John Griffin voting against it.

William Flannagan, a friend of Woodward's, immediately informed him of what had happened. "The mighty complex city of Detroit is to be reduced down to a plain scale," he wrote. Flannagan claimed that Governor Hull and Justice Witherell hired McCloskey "in their individual capacities, because the subject has never been agitated in the board, and moreover Mack [McCloskey] told me yesterday, when he produced me his new plan, that he had been requested to keep the matter secret for the present, that the governor and Judge Witherell had promised to see him well paid, and were sanguine in what they had undertaken."

On November 29, a meeting of about thirty citizens was held to discuss this change. Of all who attended, only a single individual, William Scott, spoke in favor of the McCloskey plan. As Flannagan reported, "After the matter was thoroughly discussed a motion was made for the meeting to disperse; it did so without taking any question. The commissioners are now pursuing the old plan, and they promised to make thorough work."

Although the Woodward Plan was safe for the moment, Governor Hull had grown to hate it. He was mortified when Woodward, dismissing fears of an Indian attack, proposed that the fortifications surrounding the city be removed. Woodward's suggestion could only have arisen "from his devotion to his darling child, the plan of the City of Detroit," Hull wrote just after McCloskey's plan failed to garner support.

It is deeply to be regretted that [Woodward] ever had influence sufficient to have brought that plan into existence—It is certainly the most unfortunate act of the administration of this Government—In experiment it is found to be illy adapted to the situation and circumstances of the town.Several weeks later, with Woodward yet to return, the governor and judges repealed the act incorporating Detroit into a city ("An act concerning the city of Detroit") on February 24, 1809, reverting it back to township status, as if to send the message that Detroit's top priority was military protection, not city planning. Nevertheless, the law which codified the Woodward Plan, "An act concerning the town of Detroit," was not repealed.

The Military Reserve and surrounding parcels in 1809, shown encroaching

upon Section 2 and obstructing Section 5 completely. (Source.)

Thomas Smith Returns

Detroit's urban planning activities weren't merely interrupted by the War of 1812, they were thrown into complete disarray when the occupying British officers destroyed or confiscated many territorial documents, including plans of the city. The situation was so bad when Michigan's new governor, Lewis Cass, took office in 1813, the government found it was unable to continue selling lots or issuing deeds until its land records were straightened out.

The only person capable of restoring order to the confusion was Thomas Smith, the original surveyor of the Woodward Plan. He returned to Detroit and began drawing up yet another master plan in 1816, based on his own knowledge in addition to whatever documents could be cobbled together. In assessing the "irregularities which have crept into the survey of the city," even before the war, he reported that his original plan

fell into the hands of Mr. [Abijah] Hull, (surveyor,) who drew from it several other plans, different from the original, and also differing with each other, as well in the measurement as in the numbers of lots. Deeds were issued upon all those plans, and no regular record was kept, so it became impossible to know what lots were granted or ungranted.Smith found inconsistencies in the method of numbering of lots within a section, which led to some lots being granted to more than one owner. Some deeds described lots wider or narrower than they appeared on the plan, while others inadvertently included portions of streets and alleys. Smith also reported that many lots were measured using a surveyor's chain that was too short!

Subsequently the original plan fell into the hands of Aaron Greely (Surveyor) in whose House it was seen in A broken window keeping out the weather, and in whose hands it disappeared.

This 1831 plat by John Farmer outlines discrepancies with dotted lines. (Source.)

Smith ably completed his task, albeit with much difficulty. Among his more unusual solutions in reconciling the conflicting lot numbering systems was to assign the ungranted lots two numbers. "That is of no consequence," he reported to the governor and judges, "as it is as easy to describe a lot with two numbers, as one." He also recommended that the 200 foot streets be narrowed, that the streets inside the sections be closed, and that the excess land be attached to the adjacent lots, but it doesn't appear that these suggestions were ever seriously considered.

After the years of work that went into repairing the plan, only a very small part of the city was platted accordingly. How it came to be that way will be explored in part three of this article.

Architectural Legacy of the Woodard Plan

Special thanks to Michelle and Chris Gerard, who very generously provided all of the following photographs. Click on any image to see a larger version.

The David Whitney Building - Lots 20-23, Section 8.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Although most of the lots in the Woodward Plan are ordinary rectangles, it is the plan's irregular parcels and unusually angled streets that give the center of the city its distinct character. Historian Silas Farmer put it best:

No one who studies the original plan can avoid wishing that it could have been adhered to. The portions of the city of which we are most proud and which are most admired by strangers, our main avenues, the Campus Martius, the Grand Circus, and the smaller public squares, are all parts of Judge Woodward's plan. His diagonal streets and avenues have produced several locations of special prominence which afforded exceptional opportunities for architectural display. Peculiar and pleasing vistas result in many places from the triangular intersection of streets arranged for in his plan.

—Silas Farmer, The History of Detroit and Michigan. (1884)

Metropolitan Building (rear) - Lot 67, Section 7.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Isaac Agree Downtown Synagogue - Lot 65, Section 8.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Isaac Agree Downtown Synagogue - Lot 65, Section 8.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

The genius of the Woodward Plan is that it satisfies seemingly opposite human needs--of grand, open places on the one hand, and of close and intimate urban spaces on the other--or the desires for both novelty and uniformity. Somehow they're all included, in just the right proportions, within a unified, repeatable system, still relatable two centuries after its creation.

Looking toward the interior of Section 8 from Grand River Ave. and Woodward.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Louie's Lounge - Lot 82, Section 8.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Urban Bean Company - Part of Lot 63, Section 8.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

The triangular lots at the center of each section remain public spaces just as Judge Woodward envisioned.

The Skillman Branch Library - Center of Section 7.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

The Skillman Branch Library - Center of Section 7.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Rosa Parks Transit Center - Center of Section 10.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Rosa Parks Transit Center - Center of Section 10.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Capitol Park - Center of Section 8.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Capitol Park - Center of Section 8.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Harmonie Park - Center of Section 9.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Harmonie Park - Center of Section 9.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

The Detroit Water Board Building - Center of Section 6.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

"Are cities built in a day? Can you throw them down, when your ground-plan is found contracted and inconvenient, and erect new ones on a better ground-plan, among the ruins of the old? ... No, cities are the work of time, of a generation, of a succession of generations. ... A proper and prudent foresight can alone give to a great city its fair development. Order, regularity, beauty, must characterize its original ground-plan."

—Augustus Woodward

The David Whitney Building - Lots 20-23, Section 8.

The shape of this skylight is dictated by the Woodward Plan.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Grand Circus Park.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Grand Circus Park.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

The Henry Clay Hotel, aka The Ashley - Lots 68 & 69, Section 9.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

The Henry Clay Hotel, aka The Ashley - Lots 68 & 69, Section 9.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

One Campus Martius - Lots 40-49 & 79-81, Section 7. Like the David Whitney building, the shape of the lobby and skylight reflects the block on which it stands.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

One Campus Martius - Lots 40-49 & 79-81, Section 7.

Photo courtesy Michelle and Chris Gerard.

Click here to continue to The Woodward Plan Part III: Interruptions.

Thank you so much for part II. Fascinating! And the Gerard's photography is amazing.

ReplyDeleteI always wondered why only these three streets had boulevards and why Michigan seemed to be chopped in half

ReplyDeleteAlso explains why Capitol Park is so grand, looks like the only central public space to actually be realized and preserved. Maybe Gilbert could do something behind Compuware to honor the plan

ReplyDeleteI love the Capitol Park "sample section" block analysis.

ReplyDeleteHello Paul!

ReplyDeleteThank you for posting what I have found to be the most digestible and comprehensive summary of Detroit's planning history. I would be interested in learning more about the sources you consulted to compile these posts, as this is a research interest of mine at school. I can be reached at tg268@cornell.edu! Looking forward to possible correspondence if you're available.

As I Master of Architecture student I am working on designing a city and I as a native detroiter I have been obsessed with our history, I have never delved this far into the woodward plan and can't thank you enough for all of this fantastic work! I will be citing your work in my much abbreviated analysis of Detroit.

ReplyDeletePlease be aware that Aaron Greeley Affair was more than a spat. By 1810 Greeley had surveyed all the Private Claims from Monroe N along the Detroit River to N of Mt Clemens on Lake St. Clair. He surveyed each showing all of them individually on a single page in his field books, signing each Aaron Greeley, Surveyor of Private Claims and made a very large (3ft x 6ft) drawing of them. They had to be surveyed first to define the Private Claims; outside of them was the Public Lands to be surveyed into townships and sections. The PCs were done before the Public Lands started in 1815. Besides being a US Deputy Surveyor, Greeley was a Deputy Surveyor in Canada and surveyed public lands there as did his friend Thomas Smith (who never sought work as a US Dep Sur). Greeley showed the Canadian bank of the Detroit River as well. He showed little detail on the Canadian side of the Detroit River, except for the location of Smiths house and tavern W of the current Windsor area.

ReplyDeleteHaving your own house is the dream of every person. For a middle class person, it is considered as a lifetime achievement as it requires quite a huge amount of money. Banks play a pivotal role in fulfilling this basic need. The products they offer and the services they provide are of immense use to people who intend to have their own house. For a safe and beneficial home loan, proper awareness over the products, policies, terms and conditions of the bank is most important as ignorance may result in more payments to the bank in terms of principal and interest components.

ReplyDeleteBut working with Mr Pedro changed everything in the lending experience, Mr Pedro helped me with a home loan at 2% rate which was very fast and smooth.

I will recommend Mr Pedro a loan officer and his awesome funding company Email Mr Pedro on pedroloanss@gmail.com.

Marie Carlos,

Texas USA