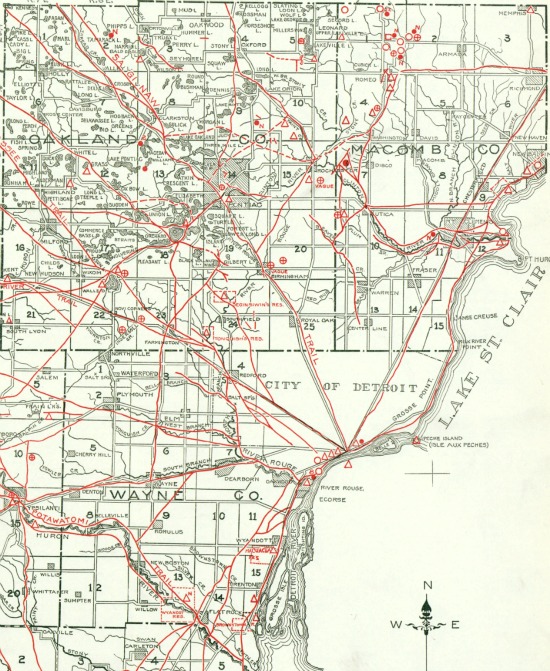

From Archaeological Atlas of Michigan, but Wilbert B. Hinsdale. (Source.)

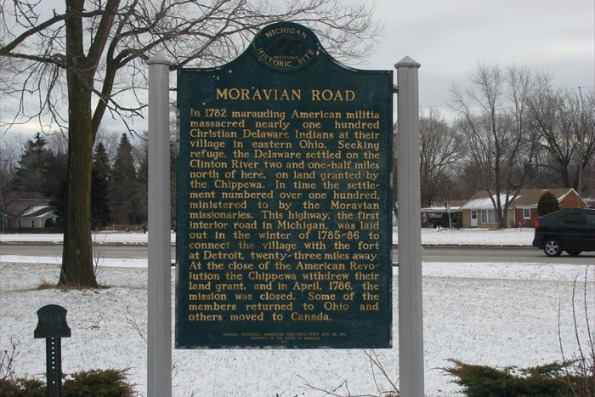

I first learned about this on a childhood visit to my grandparents' house in Clinton Township. There was a historical marker a few blocks from their subdivision, and I asked my grandpa what it said. He told me that it said Moravian Road, where it was located, was originally a trail cut through the wilderness by Delaware Indians to connect their Moravian village to Detroit.

The historical marker at Moravian Road and Metropolitan Parkway.

Image courtesy waymarking.com. (Source.)

The Moravian Trail is young, being "only" 230 years old. The establishment of Fort Pontchartrain in 1701 likely influenced the locations of some older trails, but many certainly existed since the time when the Mound Builders lived in southwest Detroit more than a millennium ago.

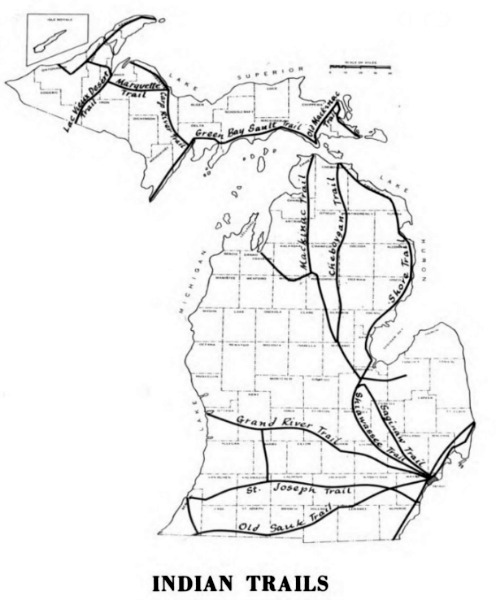

From Michigan Highways: From Indian Trails to Expressways, by Philip P. Mason. (Source.)

These trails were narrow, single-file passageways simply created by the earth being trampled along the paths most frequently traveled. But in a way, it was the land itself that created these highways. The Earth predetermines where humans will settle (on arable land, close to waterways convenient for transportation) and the most logical path between those settlements (high, dry, level land, avoiding swamps and other obstacles, and crossing rivers at their most narrow or shallow points). Some trails in Michigan trace glacial moraines deposited ten thousand years ago. Archaeologists hypothesize that roaming herds of animals were the first to travel these paths, showing the way to the hunters who followed them. When the Europeans came, they found that the best places to settle were the sites of former Native American villages, and they utilized and maintained the same trails between them.

From Archaeological Atlas of Michigan, but Wilbert B. Hinsdale. (Source.)

You have probably already heard about roads that used to be "Indian paths." This isn't a new revelation. The question I'm interested is, How do we know that a certain road was once a Native American trail?

One source is the accounts of early settlers. The Pioneer Society of the State of Michigan was founded in 1876, the year of the United States' first centennial, to preserve the memories of the first white settlers of the state's interior before that generation had completely disappeared. They described seeking out and relying on the trails for their own needs, and later expanding them into wagon trails and roads.

But we have even better proof.

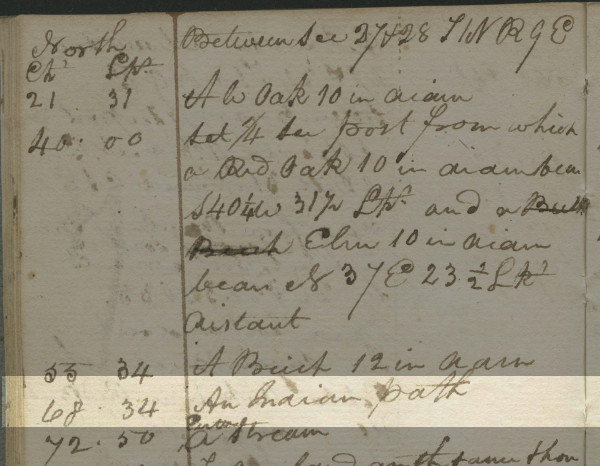

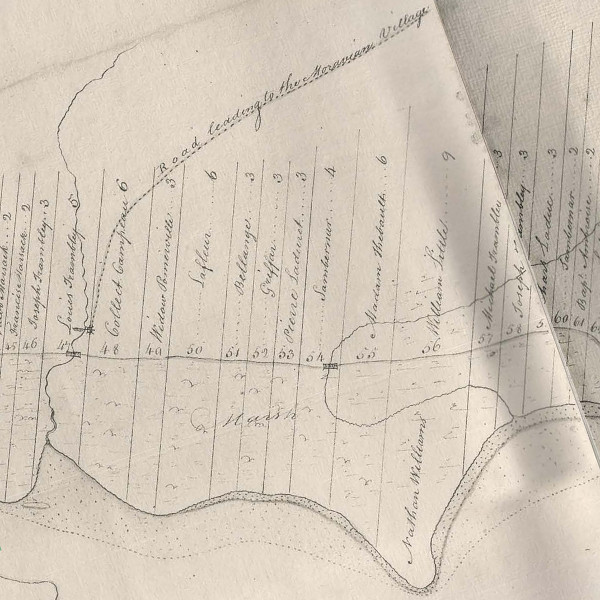

The U.S. Government Surveys

Following the 1807 Treaty of Detroit, all land in southeast Michigan that had not been settled upon before 1796 or designated an Indian reservation became property of the United States Government. In order for the land to be sold or used as payment, it needed to be surveyed. The first surveyors in southeast Michigan divided the land into six-mile by six-mile townships. At a later date these townships were subdivided into one-mile square sections. While imposing this massive grid onto the landscape, driving posts into the ground every half mile along their paths, surveyors had been instructed to note, among other observations: the condition of the soil and land; the type of timber or other growth; the boundaries of rivers, lakes and other bodies of water; and the locations of "all roads and trails, with the courses they bear." In theory, the surveyors' field notes should contain this data.

Take for example Farmington township, subdivided by Samuel Carpenter. His field notes show that he set a marker (probably a cedar post) at what is now the intersection of Farmington Road and Nine Mile Road on May 11, 1817. The post is long gone, but its exact location has been continuously preserved for nearly 200 years. Today, a modern surveyors' mark is on this very spot, protected by a cast iron cover:

A survey marker in the intersection of Farmington and Nine Mile Roads.

Image courtesy Google Street View.

The following day, Carpenter ran a line north from this point, carefully measuring the land with a sixty-six foot surveyor's chain. Below are the notes he took while running this line:

Image courtesy Seeking Michigan. (Source.)

We can see in the highlighted text that at 68 chains, 34 links (4,510.44 feet) north from the Farmington/9 Mile marker, Carpenter noted an Indian path. This is that spot today:

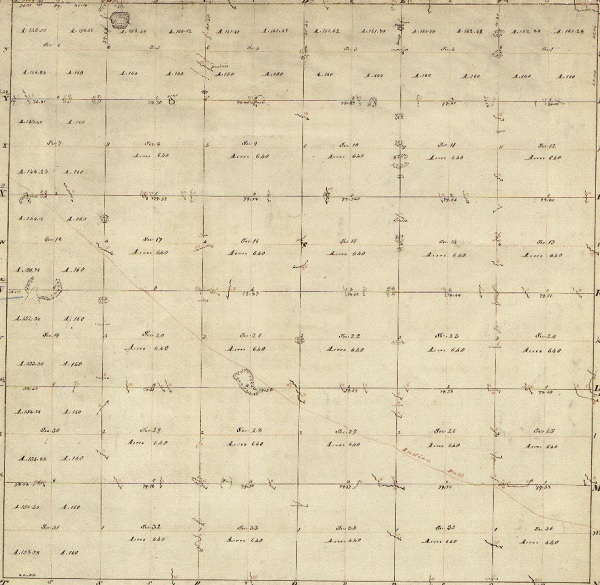

This is Shiawassee Street, once part of the Shiawassee Trail. Google Earth places the point 4,510.44 feet north of Carpenter's survey marker inside of the First Baptist Church, but this road was clearly a continuation of the old trail. Carpenter repeatedly crossed over this trail in his survey, but you don't need to read through his field notes to decode its path. The surveyors themselves drew up plats of the townships they subdivided. Below is Carpenter's plat of this township, years before it contained a single white settler:

Plat of Township I North, Range IX East of the Meridian, Michigan Territory.

The faint red line running diagonally is a Native American trail.

Image courtesy Bureau of Land Management, General Land Office. (Source.)

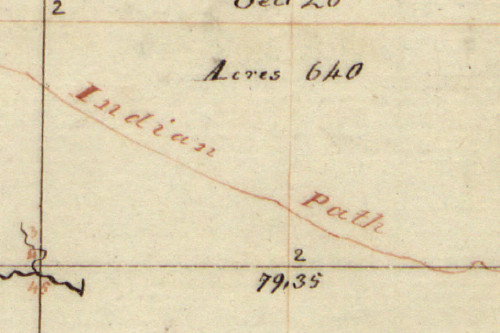

The survey plats often indicated trails with a red line.

The Shiawassee Trail in Farmington, now Shiawassee Street.

Sometimes the trails were labeled.

The Saginaw Trail in Independence Township, now Dixie Highway.

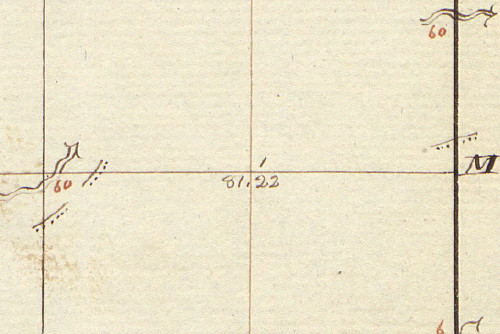

Usually paths were only indicated by a dotted line paired with a solid line, and only where they intersected the surveyor's grid.

Pieces of the Great Sauk Trail in Canton Township, now Michigan Avenue.

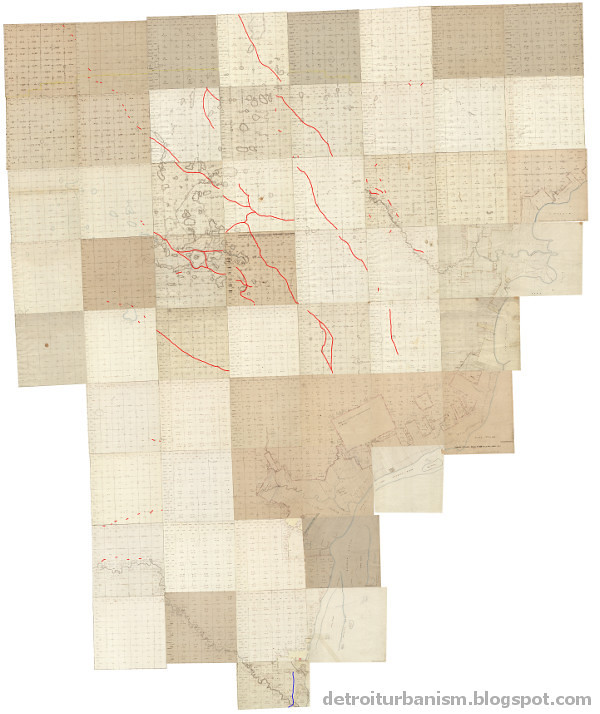

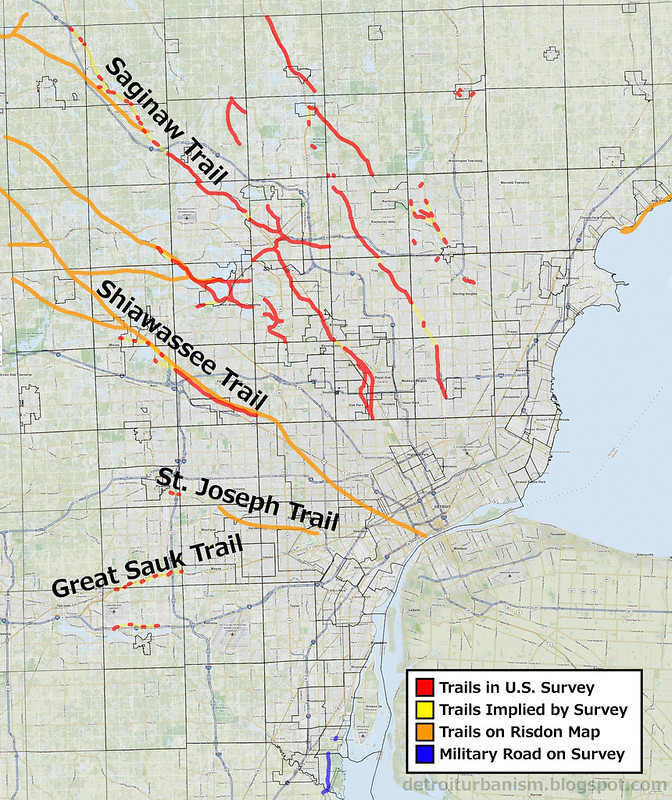

We know exactly where many Native American trails were because their locations were carefully measured in relation to markers that still exist, by eyewitnesses who were trained surveyors, years before any of the land was purchased, developed, or inhabited by white settlers. Because the grid drawn by the surveyors persists--it is what our "mile road" system is based on--it is possible to superimpose the surveyors' plats over a modern map of Metropolitan Detroit and retrace the old trails with great accuracy. Here is a composite of all fifty-eight plats that comprise the tri-county area with trails highlighted in red. Near the bottom is the military road to Urbana, Ohio, denoted in the surveys, highlighted in blue.

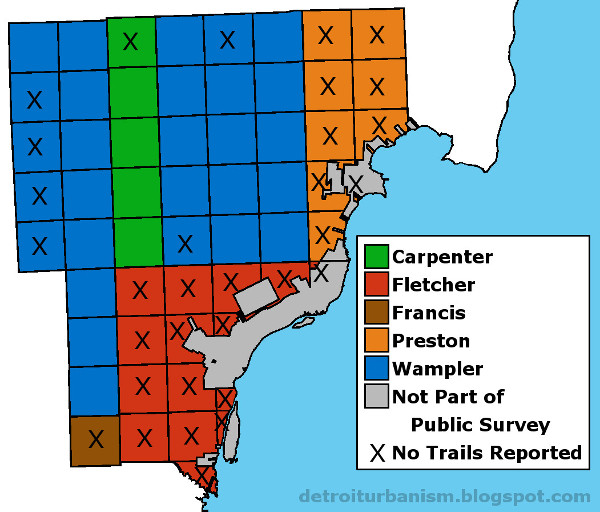

This image isn't quite ready to trace onto a modern map. There are some obvious gaps in the trails. Why are most of Macomb and Wayne Counties devoid of any paths? To find the answer, I looked into who was doing the surveying. All of the townships that comprise the tri-county area were subdivided by five surveyors (and their crews): Samuel Carpenter, Joseph Fletcher, Joseph Francis, William Preston, and Joseph Wampler. Below is a map showing who subdivided which township. Townships that did not indicate any Native American trails on their plats or in their field notes are marked with an "X." Do you notice any patterns?

Surveys of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb Counties, 1815-1823.

Isn't it strange that four out of five townships surveyed by Carpenter and Wampler contain trails, while Fletcher, Francis and Preston show a combined total of zero? Maybe these men misunderstood their instructions. Negligence might also have played a role. Fletcher was originally contracted to survey an area close to the Points of Origin for the Michigan Survey, but his work was so flawed that it had to be redone by Wampler. Unfortunately, Fletcher's surveys included all of the modern City of Detroit. We may never accurately know the locations of the Native American trails in the city.

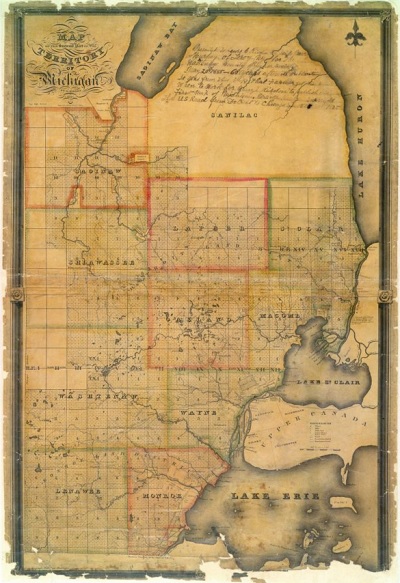

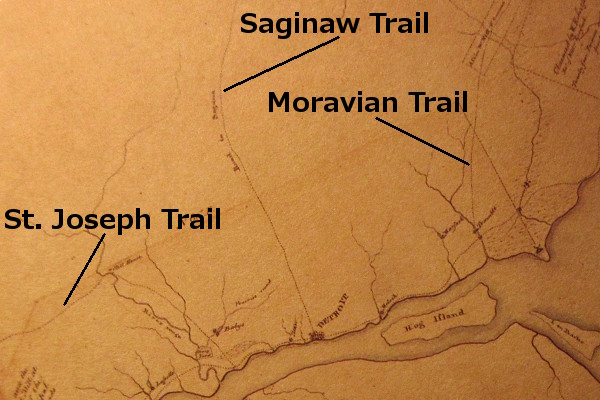

The Orange Risdon Map

In the 1820s, Michigan was on the verge of a massive influx of both homesteaders and speculators seeking cheap land. The southeast part of the territory had been surveyed and was up for sale. Orange Risdon, himself a professional surveyor and well-traveled explorer of the area, tried to capitalize on the mass immigration by producing a detailed map of the region. He utilized government surveys and his own firsthand knowledge to create a map that would help land purchasers make informed selections.

Map of the surveyed part of the territory of Michigan, by Orange Risdon. (Source.)

Risdon published an advertisement in the October 1, 1824 edition of the Detroit Gazette in order to gain early subscribers of the map, which would be published the following year. In the ad, Risdon stated:

"The publisher, having spent some time in exploring that junction of the territory embraced in his map, will be enabled to locate the most important Indian paths, which as they were made by those who were acquainted with every part of the country will be an important guide in the future location of our roads."Risdon's map uses dotted lines to indicate Native American trails, including the portion of the Shiawassee Trail missing from Fletcher's surveys. Some trails had already been replaced by straight, surveyed roads by the time the map was produced, but enough remained to fill some of the surveyors' omissions.

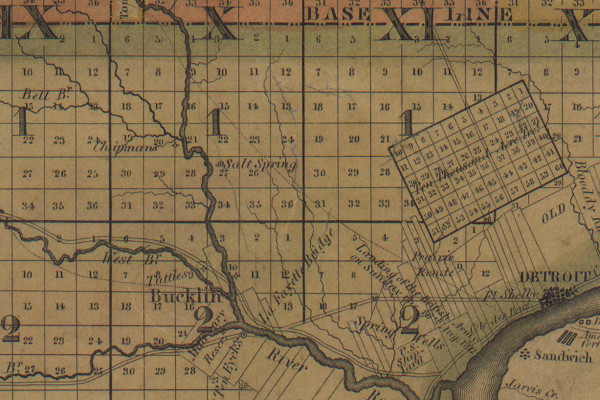

Detail from Map of the surveyed part of the territory of Michigan. (Source.)

Near Bucklin (modern Dearborn) is the St. Joseph Trail.

Leading northwest out of Detroit is the Shiawassee Trail.

Below is an image that superimposes the trails seen on both Risdon's map and the U.S. surveys onto a modern map of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb Counties.

The Native American trails of Metropolitan Detroit.

Click here for a larger version of this map.

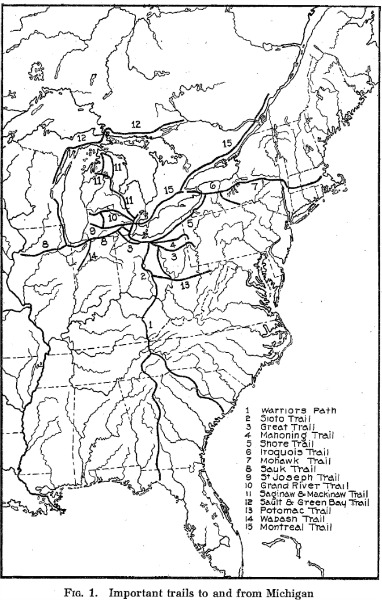

Important Trails Around Detroit

The Saginaw Trail • Ran northwest out of Detroit to the Saginaw River. The site of the settlement at Pontiac was chosen because it was where this trail crossed the Clinton River. North of Pontiac, the Saginaw Trail is mostly preserved as the Dixie Highway. But the winding footpath between Detroit and Pontiac was supplanted by the straight and rigid Woodward Avenue in the 1820s. Even this incarnation of Woodward is not quite the same as today's route. There used to be an abrupt jog in the road in Royal Oak to avoid a swamp. The road turned right at what is now Lafayette Avenue, which used to continue to what is now Crooks Road, where it turned left, then continued to Pontiac. I believe that a portion of Lafayette Avenue traces the old Saginaw Trail, which was bypassing the same swamp. Below is an animation showing this road in the 1817 government survey, an 1872 map, and a modern satellite image.

The Great Sauk Trail • Also called the Chicago Road. It ran west from the Rouge River near Detroit, terminated at Rock Island, Illinois on the Mississippi River. In the 1820s, the trail was used as the foundation of a military road to Fort Dearborn at what is now Chicago. This road exists today as US-12.

The St. Joseph Trail • Also called Territorial Road. It connected the Rouge River near Detroit to the St. Joseph River of Lake Michigan, passing through Jackson, Battle Creek and Kalamazoo. The highway that coincided with the trail was originally marked as US-12 before that designation was transferred to the Chicago Road in 1962.

The Shiawassee Trail • Began just west of Detroit according to Risdon's map, ran northwest and connected to the Shiawassee River at the present site of the Village of Byron. It then followed the Shiawassee River downstream to the Saginaw River. The site of Farmington was chosen by its founder Arthur Power because it was where the Shiawassee Trail crossed the Rouge River.

The Moravian Trail • Cleared of timber in the winter of 1785-86 by Delaware (Lenape) Indians who were members of the Moravian Missionary on the Clinton River. The trail ran southwest from the mission along the Clinton River likely where Moravian Road is today. It continued south through what is now Warren, then took a slightly southeasterly course to Connor's Creek on Detroit's east side. The Fort Gratiot Turnpike later replaced the trail as the northeasterly road out of Detroit.

(There are other roads I haven't mentioned which, even though they appear on Hinsdale's map at the beginning of this entry, may not actually be native American in origin. These will be discussed in a future post.)

Detail from Patrick McNiff's Plan of the Settlements at Detroit, 1796. The Moravian Trail ended at Conner's (formerly Trombley's) Creek close to the Detroit River.

Image courtesy Detroit Historical Society. (Source.)

Native American trails near Detroit in 1797.

Detail from A Rough Sketch of Part of Wayne County Territory by Robert King.

Source: Brian L. Dunnigan, Frontier Metropolis: Picturing Early Detroit, 1701-1838.

Our map was not a blank canvas when Cadillac landed in 1701. Sometimes we assume that the tribes pushed out of southeast Michigan left without a trace, even as we drive along the pathways they built, unaware of their origin. The land was worked and shaped by those who had preceded us since time immemorial, and the Earth bears witness to this fact.

I'm pretty sure the Saginaw Trail is still visible in Royal Oak. Crooks road turns due north just south of 13 Mile. On the west side of the road there is an historical marker and the ground has a clear worn-out path running through it.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.coheadquarters.com/PennLibr/HistoricRO/StateMarkers/IndTrailMarker.htm

I've read about that before, it's awesome that it's preserved. Even though that site is very old and historically important, I believe based on the old maps and surveys that that depression in the ground comes from the first 1820s version of Woodward and not the Native American footpath. I will definitely have to research it in more detail. Thanks!

DeleteI was actually just looking at that trail on the map, as I live right down the street from the marker and have always been intrigued by it. Here's some details behind the plaque and Starr house - http://www.royaloakhistoricalsociety.com/almonstarrindiantrail.html

ReplyDeleteFrom laying the survey over a modern map of the area it doesn't seem they correctly align to this location, but perhaps there's another explanation for this.

Another trail that was well-documented in the survey and aligns nicely is Orion road through Goodison, following Paint Creek.

Great work!

The Shiawassee Trail Follows Shiawassee Road (marker on Shiawassee just west of Inkster Rd) It's important to note that the area of Inkster to Beech Daly, and 8 to 9 Mile roads, was one of two Indian Reservations in Southfield; this one was called Tonquish after it's CHief, yes the same one as buried in Westland. I really wish we would document and display these facts.

ReplyDeleteThank you for this information, and yes angered, we should.

DeletePaul, Very interesting, I would like to thank you for your hard work and dedication to this investigation. You have certainly opened a few new doors of understanding for me. I really enjoyed how you have presented this. I think I may differ on a few points as this blog continues.. but for now, I will have to find two of your maps I have never seen before, and re-examine some others, so we can be on the same page. Great Job!

ReplyDeletePaul, Very interesting, I would like to thank you for your hard work and dedication to this investigation. You have certainly opened a few new doors of understanding for me. I really enjoyed how you have presented this. I think I may differ on a few points as this blog continues.. but for now, I will have to find two of your maps I have never seen before, and re-examine some others, so we can be on the same page. Great Job!

ReplyDeleteThank you, Kurt! In trying to cut my posts down to a readable length, some details or explanations might be glossed over, but I'd be glad to explain any points that may not have made sense. Or if you need to know the source of any of the maps I posted, I'll be happy to link to the source. And of course I'm open to correct any errors I might have made. :) (Honestly I'm learning a lot of this as I go!)

DeleteI have heard that about an Indian trail near the Starr House. I have also read somewhere that in Wagner Park in Royal Oak, located between Main Street and Rochester Road north of 12 Mile Road, you can see a depression that cuts across the park - this was also part of an Indian trail. Can anyone confirm that?

ReplyDeleteTraci -- The trails on the 1817 survey do not overlap the present site of Wagner Park, but a stream used to run through it. Here is an 1872 map superimposed over a modern satellite view: https://c2.staticflickr.com/2/1482/24142565109_ed0ef08497_o.jpg

DeleteI am a Wayne County native, history buff, and cartography geek, and this may be the most interesting and informative blog post I've ever seen. You may be an amateur, but I think this is impressive research--and I AM an academic researcher! The amount of work that went into producing this piece is truly impressive. Awesome job, and thank you for your efforts!

ReplyDeleteThank you for all of what you've brought together here. Some years ago I copied this image that shows how of these trailed were continued across the Detroit River into Canada: https://www.flickr.com/photos/mita/2392454030/ I believe it might have come from this book (http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002746637) but I'm not sure.

ReplyDeleteI just discovered your blog and am now following.

ReplyDeleteThis post in particular is excellent - - thank you for your time and research.

Interesting! I'm Algonquin from Quebec Canada

ReplyDeleteWhen Cass, Wing and other prominent gentlemen from Detroit decided to dispel the "interminable swamp" notion and prove Oakland County and the rest of the state above 8-Mile was not only habitable but preferable for Easterners to settle on and raise families and crops, they went north on the Saginaw Trail past Royal Oak and then somewhere around 14-Mile headed NW to connect with the trail that is next to Wing Lake. They reported this in a November edition of the Detroit Gazette. Our question is: what was the impetus to head NW? They were on horseback so it must have been more than a footpath. Any thoughts? This is an incredibly researched project and is very helpful to the local historians who have posited the trail information but have not been able to provide the necessary documentation. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteMichael Carmichael, Bloomfield Historical Society

I do not believe that Cass attended the expedition described in the November 13, 1818 Detroit Gazette piece. Cass did, however, travel north to Saginaw in 1819 and would have passed through Oakland County then. The footpaths were described as being about 18 inches wide, so there is no reason horses couldn't have traveled over them. Many old pioneer accounts describe folks riding horses and even driving oxen along them. Once the 1818 exploration party got into what is now Oakland County, they departed from the Saginaw trail and followed the surveyor's lines.

DeleteRegarding why the 1818 exploration party took the path that it did: First, I would guess that traveling northwest was simply the most direct way to travel toward the interior of the peninsula. Second, each person whose name appeared on that Gazette piece, except for Rev. John Monteith, was a member of the Pontiac Company. A few days before that piece was published, the Pontiac Company was chartered and land was purchased for a settlement where the Saginaw Trail met the Clinton River. These investors would have been interested in attracting homesteaders along the path between Detroit and Pontiac. I don't yet know if these investors knew where they wanted Pontiac to be located based on government surveys, or if part of the point of the expedition was to check out multiple possible locations and then choose the best spot. I would love to one day write a full-length piece about the expedition.

The Gazette piece described the land just north of Detroit and south of 8 Mile: "That flat land in the rear of our city which has been a barrier against explorers and which has been called a swamp, is not a swamp, but is rich land, covered with large timber and though in certain seasons it is wet, it is now perfectly dry. ... We passed through 8 miles of land that is but little undulated, yet sufficiently so as to afford many good habitations for farmers. The soil is of good quality, and every where sandy and remarkably loose."

P.S. For what its worth, the report notes that Oakland County's farmland isn't the best, but references land in Livingston and Shiawassee counties, which had recently been surveyed by Joseph Fletcher, was the most excellent:

Delete"It appears by information of Indian traders and surveyors, that the part of the territory we have thus imperfectly described is by no means the best. We have been assured from unquestionable authority that Mr. Fletcher who surveyed the interior of this territory, and who has for 30 years been employed in surveying in various parts of Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio, has frequently asserted that he had never surveyed 20 townships of land in a body of a quality so uniformly excellent as 20 townships north of the Huron [Clinton], on the upper branches of the rivers that fall westerly into lake Michigan."

To be fair, though, Joseph Fletcher did not survey any townships in what is now Oakland County.

Paul, I'm a couple years late on this, but what tool did you use to create the composite of the fifty-eight original plats? I stumbled onto this blog while halfway through my own attempt to create a trail map from the survey plats, and while you beat me to it, I can't be upset because the result is so interesting and well-done. I've been cropping the images from glorecords.blm.gov to just the plat and then placing them as image overlays in Google Earth Pro, but that approach has some serious ups and downs. The result is a searchable overlay on the modern map, but inconsistencies mean the plats don't actually align correctly with the modern map and placing them as separate overlays produces a .kmz file rather than a composite image I can save and use elsewhere. Really curious to know how you approached the problem.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThank you for this incredibly informative and fascinating post. It will be extremely helpful to a book I'm writing about a land speculator in 1830s Michigan.

ReplyDeleteHi Paul,

ReplyDeleteI appreciate your work and contributions.

I wonder if you know about Mulvey Road (a short stretch of road) in Fraser—if it had been a Native American trail. I find this claim super perplexing and curious. Because according to the Atlas of Early Michigan’s Forests, Grasslands, and Wetlands, most of Mulvey Road would have been traveling through shrub swamp. A good place for snakes.

The claim is made by the authors of Images of America: Fraser. “… Mulvey Road, the oldest street in Fraser, was originally a Native American trail.” A book with no sources.

So I emailed the Fraser Historical Commission asking for the source(s), because a few of its members are also a few of the authors of the book. So far I’ve been met with good ol silence. I plan to keep asking through others means, but figured to inquire here too. Either way, thank you!

I also find the claim that Mulvey was a Native American trail perplexing. It's not shown on the original government survey plat, but then again it looks like that particular surveyor (William Preston) didn't show Native American trails on any of his plats. But he does show a swampy area on what is now Garfield Road just south of Mulvey. I also notice that the path is not in Hinsdale's atlas.

DeleteI see the road on this 1859 atlas:

https://shelbyhistory.tripod.com/1859_wall_map_of_macomb_county/Clinton_.JPG

On that map it looks like what is now 14 Mile Road did not continue east of Mulvey, so this area might have been a little swampy too. My guess is that the area through which the Harrington Drain runs was swampy, and that Mulvey Road in addition to Fruehauf/Klein Roads bypassed it. I would also guess that these started out as "desire paths" by the early white settlers before they were eventually recognized as public roads.

Also, with Moravian Road nearby traveling in the same direction, it's not clear why Mulvey Road, running just about a mile, would crop up nearby.

That helps paint a preliminary picture in my mind, thanks (erroneous or not so much, excuse my ignorance; and I'm relying on the atlas I had mentioned, Atlas of Early MI's Forests, Grasslands, & Wetlands, to be more or less accurate):

ReplyDeleteMulvey was never a Native American trail. Most of Mulvey had been covered in swamp. The only part not covered in swamp started somewhere between today's Harrington and Nicola Drives till 14 Mile: this stretch was upland forest. Thankfully the old St John Cemetery (right there, very near the intersection of Mulvey & 14 Mile) kinda preserves this upland-forested topography. (I wonder if it was ever referred to as the cemetery "on the hill".)

Mulvey merely connected 14 Mile to Garfield. The ditch (Harrington Drain) would have had to precede Mulvey, hence Mulvey's directional situation. (Again, I know almost nothing about the ways early settlers could have drained such immensity of wetland.) Maybe it was this ditch that deterred road development east of Mulvey, since the Drain does travel south, crossing 14 Mile, where the ecosystem turned to wet prairie till about today's Miller Park in Warren.

Looks like Fruehauf/Klein Roads were in mesic forest, neatly skirting around the wetter ecosystems. PS in case you don't know, the Michigan Natural Features Inventory provides an interactive online version of their Atlas.