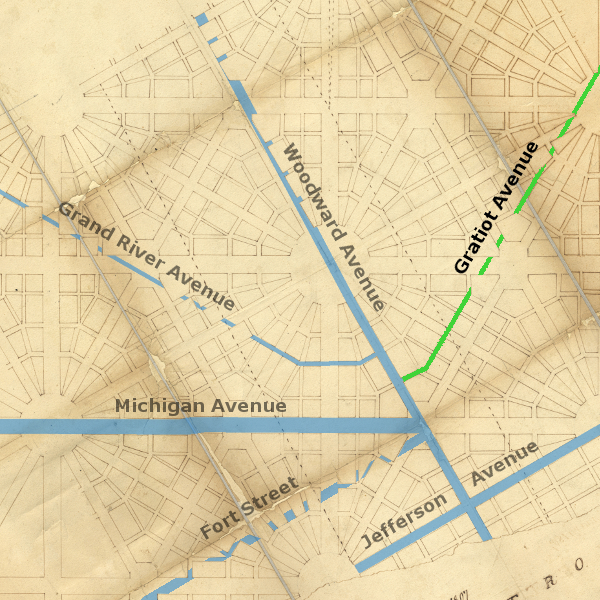

Like Woodward, West Jefferson, and Michigan Avenues, Gratiot Avenue was established in the early 19th century as a military road. But unlike previous radial avenues, it wasn't an extension of a radial avenue on the Woodward Plan, and it did not coincide with an Indian trail.

There was a road near Detroit leading northeast constructed by Lenape (Delaware) Indians in the late 18th century. They were Christian converts of the Moravian Church and founders of New Gnaddenhütten, a small village on the Clinton River in what is now Clinton Township. Led by Chippewa guides, they cleared a path from their settlement to Conner's Creek in the winter of 1785-1786. Parts of Moravian Road supposedly preserve its original path. But when this road is compared to the location of Gratiot Avenue, there doesn't appear to be any correspondence.

Fort Gratiot

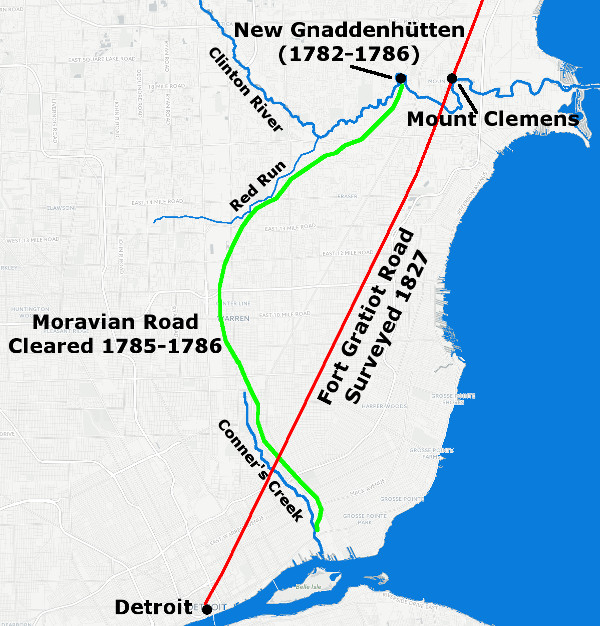

In May of 1814, the US government established a fort at the head of the St. Clair River in what is now Port Huron. The fort was named after the US Army engineer who oversaw its construction, Captain Charles C. Gratiot.

An 1839 plan of Fort Gratiot.

Image courtesy of Seeking Michigan. (Source.)

Although Fort Gratiot was vacated in 1821, it was considered to be essential in the event of another war with Britain. An 1826 report of the Congressional Committee on Military Affairs on the subject of military roads stated in part:

[T]o give that quarter of the country [Michigan] the security that its importance to the Union requires, the aid of the government is loudly called for, in the laying out, opening, and constructing roads in this section of the territory. ... With this view of the subject, your committee recommend that provision be made for surveying a road from Detroit to Fort Gratiot, at the outlet of Lake Huron.The report included a memorial from Governor Lewis Cass, who wrote:

From Detroit to Fort Gratiot, at the entrance into Lake Huron, is about fifty-six miles. This is an important military position, and will unquestionably be occupied in every future war. But it has been already shown, that this point cannot be reached by water while an enemy is in force on the opposite shore. In such a contingency, it must be abandoned, or in the intercourse must be preserved by land. This intercourse is also essential to our command of Lake Huron, and to a communication with the posts upon it, and upon the straits of St. Mary [Sault Ste. Marie].

The Surveyors

On March 2, 1827, Congress passed An Act to authorize the laying out and opening of certain roads in the territory of Michigan. The law empowered the President of the United States to "cause to be laid out a road from Detroit to fort Gratiot, at the outlet of Lake Huron." He was also authorized to appoint three commissioners--at least one of whom was required to be a surveyor--to "explore, survey, and mark" the road "in the most eligible course." The commissioners were to submit a plat and field notes to the President for approval. The law stipulated that they were to be paid $3.00 per day for their work, and their assistants $1.50 per day.

The commissioners appointed by President John Quincy Adams were Hervey Parke of Pontiac, Amos Mead of Milford, and Conrad Ten Eyck of Dearborn.

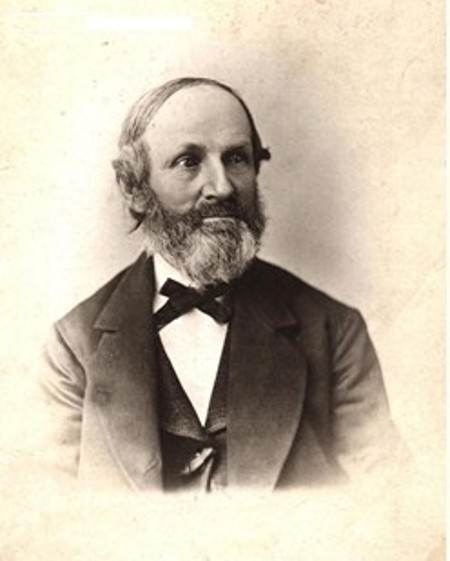

Hervey C. Parke, surveyor of the Fort Gratiot Road. (Source.)

Hervey Parke was the surveyor of the group, having arrived in Michigan to engage in surveying in 1821. (You can read his interesting account of traveling through Detroit and Oakland County when he first came to Michigan here.) Amos Mead was born in Vermont and came to Oakland County in 1825, having received a land grant in what is now Milford for his service in the War of 1812. From 1827-1833, Milford was part of Farmington Township, and Mead was elected Farmington Township's first supervisor. Conrad Ten Eyck, a New York immigrant, had been a successful businessman in Detroit before building his famous tavern on the Chicago Road in 1826.

A Peculiar Placement

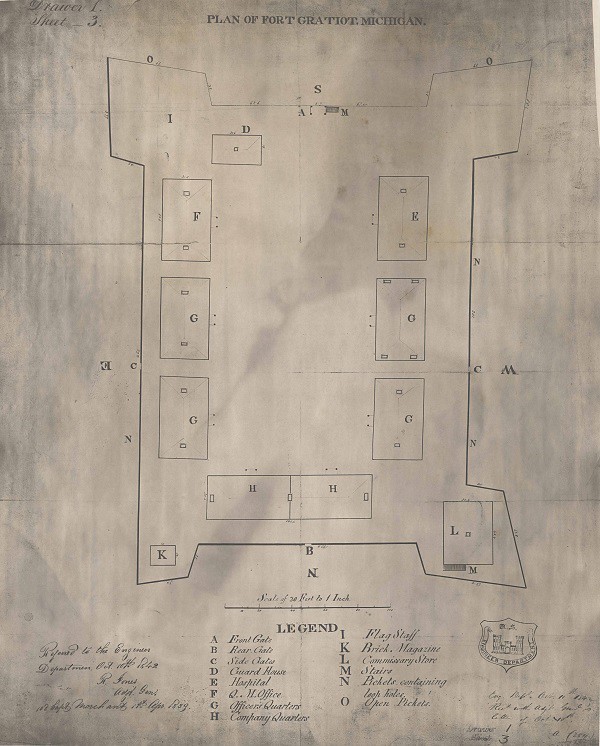

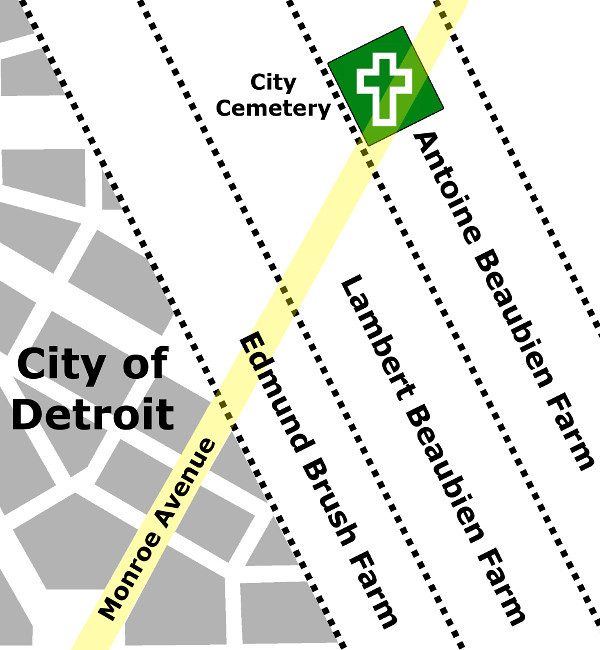

According to Augustus Woodward's Plan of Detroit, a 120-foot-wide avenue was supposed to extend from the city's Point of Origin at Campus Martius at a bearing of N 30° E. Only a small part of this avenue was ever built--Monroe Avenue between Campus Martius and Randolph Street. Just as the surveyors of the Chicago Road incorporated Michigan Avenue into their survey, making their road an extension of an existing radial avenue, the most logical design of the Fort Gratiot Road should have extended from Monroe Avenue. However, the surveyors chose instead to incorporate a narrow side street one block north of Monroe Avenue. Had the Woodward Plan have expanded eastward, this new road would have conflicted with it.

Gratiot & Monroe Aves. in Philu E. Judd's 1824 rendition of the Woodward Plan.

Why wasn't the road to Fort Gratiot made as an extension of Monroe Avenue? According to historian George B. Catlin, it had to do with the farm immediately east of the city, the border of which is now Randolph Street. In the Spring 1929 issue of Michigan History Magazine, Catlin wrote that the farm, owned by Edmund A. Brush, included "a fine orchard which would have been spoiled had that connection been made." This claim is repeated in Edith Forster's book Yesterday's Highways: Traveling Around Early Detroit (1951), as well as Robert Goodman and Gordon Draper's documentary Detroit's Pattern of Growth (1965). However, I haven't found any corroborating evidence of the Brush orchard story predating Catlin's 1929 article.

A more likely explanation lies east of the Brush property, on the former Antoine Beaubien farm. When Detroit's old cemeteries had become practically full, the City Council directed in 1826 that a new burial ground be established outside of the city limits. In March of 1827, the city reached an agreement with Antoine Beaubien to purchase two acres of his farm for $500, and the sale was officially executed the following June 1. Unfortunately, the new cemetery lay directly in the path of where an extension of Monroe Avenue would have run.

It is certainly an odd coincidence that this sale was being negotiated at the same time the commissioners of the Fort Gratiot Road were being appointed, but this appears to be the reason why Gratiot Avenue was not simply made an extension of Monroe Avenue. By beginning the military highway on the side street to the north, it was able to bypass the new burial grounds completely. The use of this property as a cemetery has long since been discontinued. Bodies were disinterred beginning in 1869 and the grounds were converted into a park, which was ultimately sold.

The Survey

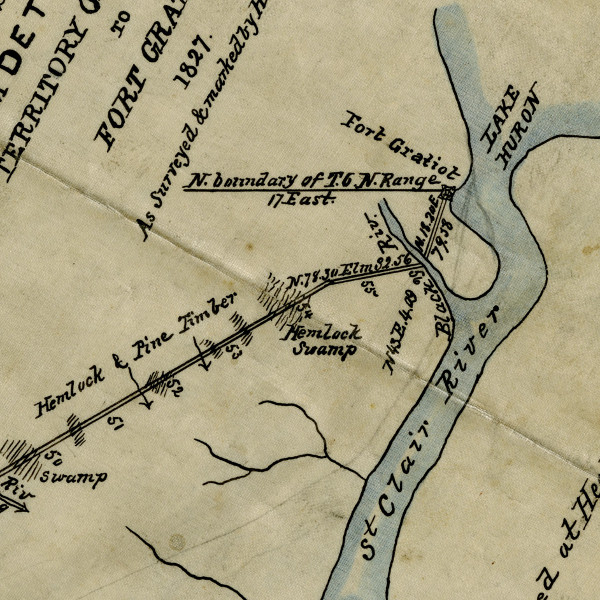

Detail from an 1871 copy of Parke's Fort Gratiot Road survey.

Image courtesy of the Clarke Historical Library, Mount Pleasant, Mich.

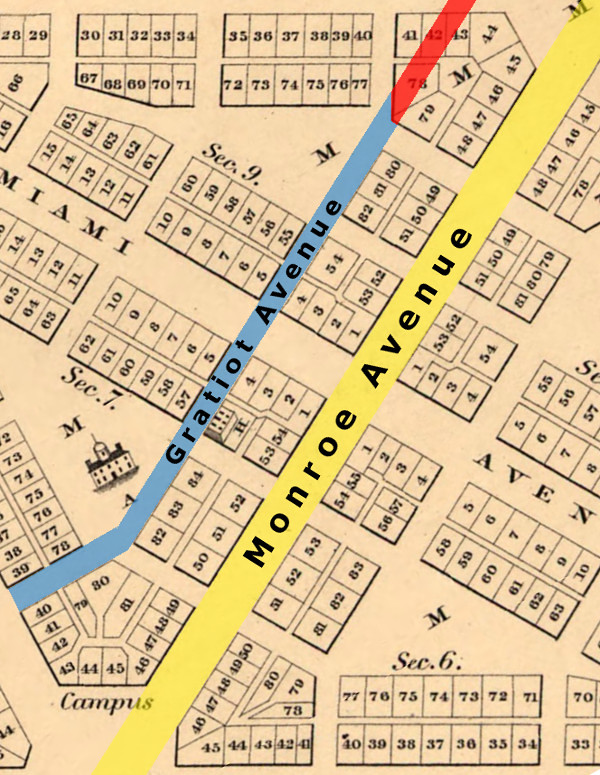

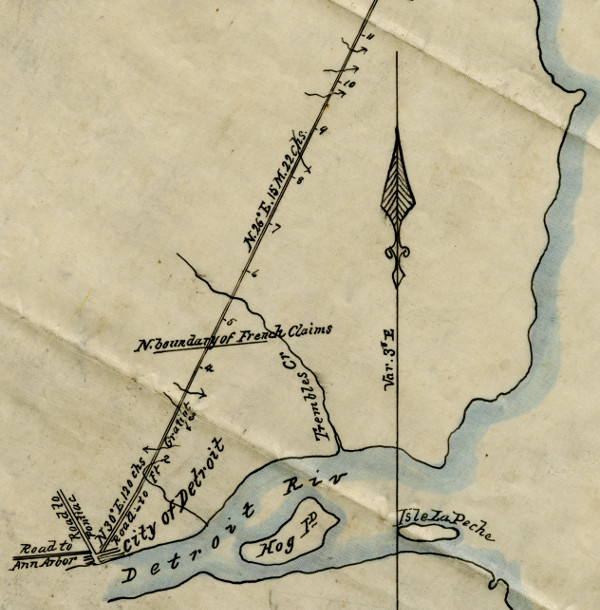

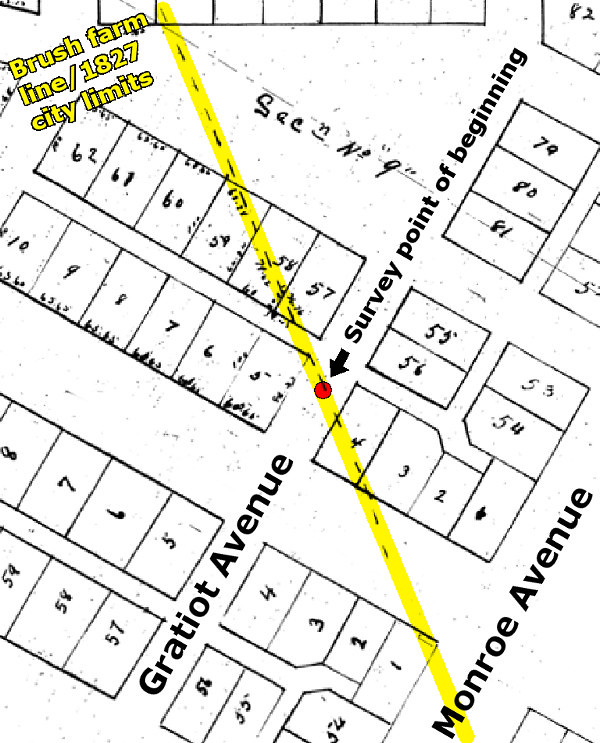

In June of 1827, using a theodolite and a Gunter's chain, Hervey Parke and his crew surveyed a line that was to be the center of the road, carefully measuring its direction and distance, and driving wooden posts into the ground every mile or turning point. The survey's point of beginning was recorded in Parke's field notes as

Commencing at a post standing on the NEly [northeasterly] side of the City of Detroit in the centre of a street between Lots No. 4 & 5 in Section No. 9.The city's eastern border at the time coincided with the beginning of the Brush Farm, approximately where Randolph Street lies today. Section Nine of the Woodward Plan was the triangle bounded by Madison, Miami (later renamed Broadway), and Monroe Avenues. And lots four and five of this section were at the northwest and northeast corners of the intersection of Miami Avenue and a sixty-foot-wide side street.

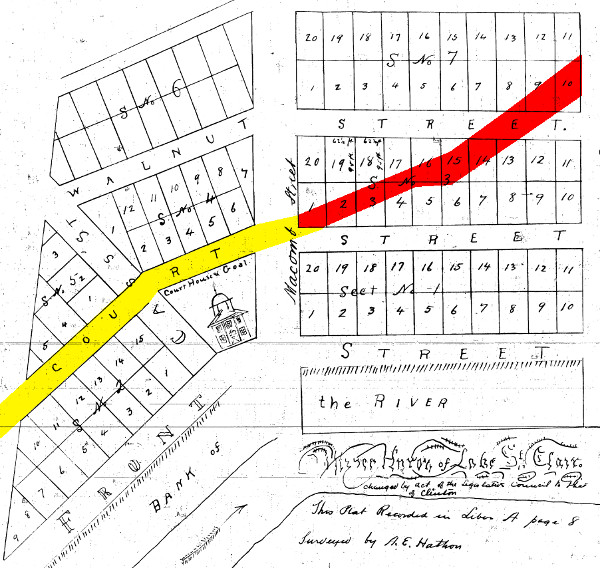

The Point of Beginning for Parke's survey, according to his field notes.

Background image: Abijah Hull's 1807 rendition of the Woodward Plan.

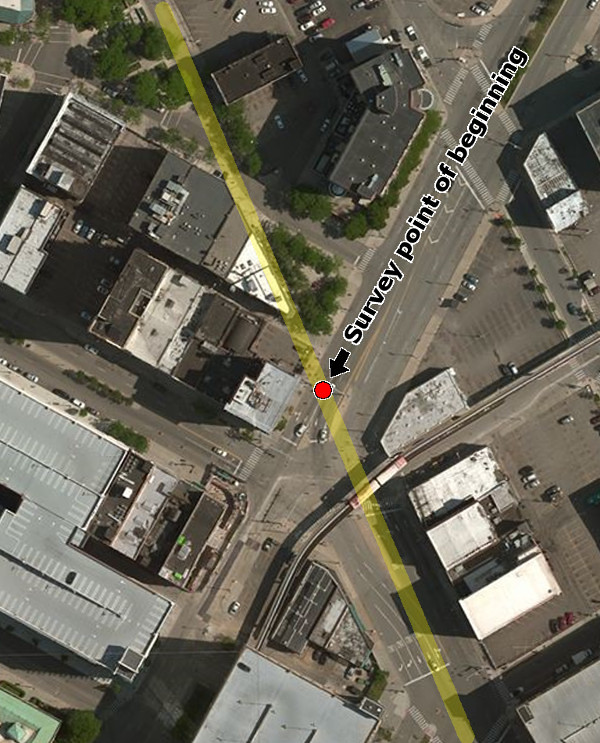

Gratiot Avenue's Point of Beginning today.

Detroit's 1827 border is highlighted in yellow.

This point was considered the beginning of "Gratiot Street" until July 9, 1867. Before then, the segment of the road between Woodward Avenue and Randolph Street was known as East State Street. On May 6, 1874, Gratiot Street became Gratiot Avenue.

From the Point of Beginning, Parke's line followed a bearing of N 30° E, the Woodward Plan's prescribed direction for Monroe Avenue. After 1.25 miles, near the present-day intersection of Dubois Street, the angle of the road changed to N 26° E, and stayed on that course for 15.28 miles, until reaching a point close to today's Quinn Road.

On the third day of the survey, Parke's crew planted mile post number twenty in Mount Clemens. Parke seamlessly joined new road with the village plat of Mount Clemens, which was set down in 1818. Parke appropriated a segment of Court Street and made it part of the Fort Gratiot Road. But to continue it, he found it necessary to cut through multiple lots of the village plat. Because a segment of the road cutting through these lots was especially narrow, an apocryphal story developed that the land was an orchard owned by Christian Clemens, and the road was forced to pass between two rows of fruit trees. Of course, it's doubtful that Clemens would divide a valuable orchard into town lots that he had no intention of selling or developing.

The path of Gratiot Avenue as it cut through Mt. Clemens.

Background image: The original 1818 plat of the village.

Downtown Mount Clemens today.

A History of St. Clair County, published in 1883, included the recollection of an individual who, at the age of eighteen, worked as a chainman on the Fort Gratiot Road survey team. The man, whose name was not included in the text, relays the difficulties encountered as the crew worked northward:

From Mount Clemens we took as straight a line as we could for Fort Gratiot. About four miles south of Belle River, we struck a heavy windfall of timber, where we camped for the night. The next morning we started on, creeping as we could through the dense mass of fallen timber, and halted at noon on the bank of Belle River for our cook and packer to come up with provisions. Here we waited until next day, enduring a fast of thirty hours. The windfall proved to be of much greater extent than we had supposed, and, in seeking to get around it, our cook and packer had to travel many miles eastward, and then work their way back to strike our lines. Though deprived of our tent and provisions, and feeling the keen demands of appetite, we had rather a social time, as Deacon Erastus Ingersol, of Farmington, the axman of the party, told several stories of a funny character. The deacon was a large, fleshy man, and, it being warm weather, he had divested himself of coat and vest, retaining only his pants and a thin cotton shirt to protect him from the hordes of mosquitoes that sought to refresh themselves from the deacon's store of blood. With the aid of punk, flint and steel, carried by one of the party, we succeeded in getting up a fire; but despite the smoke, in which the deacon sought to hide from his tormentors, he had a hard time of it.

Erastus Ingersoll, axman on the Fort Gratiot Road survey crew, and first white settler in Novi, which in 1827 was part of Farmington Township.

Image courtesy of the Novi Public Library. (Source.)

The last eighteen miles of the line intersected multiple swamps, marshes and streams in densely forested land. The survey crew finally arrived at Fort Gratiot just twenty-seven feet short of fifty-seven miles from the Point of Beginning.

Detail from an 1871 copy of Parke's Fort Gratiot Road survey.

Image courtesy of the Clarke Historical Library, Mount Pleasant, Mich.

Roadwork Begins

Although the survey was promptly approved and recorded, no action was taken toward the road's construction for more than one year. On December 5, 1828, the House of Representatives passed a resolution introduced by the Michigan Territory's delegate Austin E. Wing, which called upon the Secretary of War to report to Congress estimates for building the Saginaw and Fort Gratiot Roads, and to give his opinion on their relevance regarding national defense. Secretary of War Peter Buell Porter delivered the report before the end of the month. Regarding the roads' military importance, he referred to Governor Cass's memoir in the Committee on Military Affairs' 1826 report on the subject, quoted earlier. As to cost estimates, Porter included a report from Charles Gratiot, who had since been promoted to Colonel. Col. Gratiot wrote, "The country traversed by the road to Fort Gratiot being represented, likewise, as heavily timbered, will render necessary an expense equal per mile to that of the Chicago road; and the length of this road being about sixty miles, there will be required for its construction $30,000." But "with a view of obtaining an appropriation at the present session" of Congress, Col. Gratiot suggested an initial installment of $15,000.

Charles Chouteau Gratiot (1788-1855)

Following Gratiot's advice, Congress passed a $15,000 appropriation for the road on March 2, 1829. Major Henry Whiting of the US Army was made superintendent of the project. In Col. Gratiot's 1829 Report of the Chief Engineer, he stated, "seventeen miles (of the Fort Gratiot Road) have been put under contract, a considerable portion of it completed, and the remainder is in a state of forwardness."

Congress appropriated an additional $7,000 on May 31, 1830. Col. Gratiot reported that November that seventeen and a half miles have been completed "with the exception of some repairs," and additional contracts having been made "to the end of the thirty-second mile from Detroit." In March 1831, Congress earmarked $8,000 more for the project.

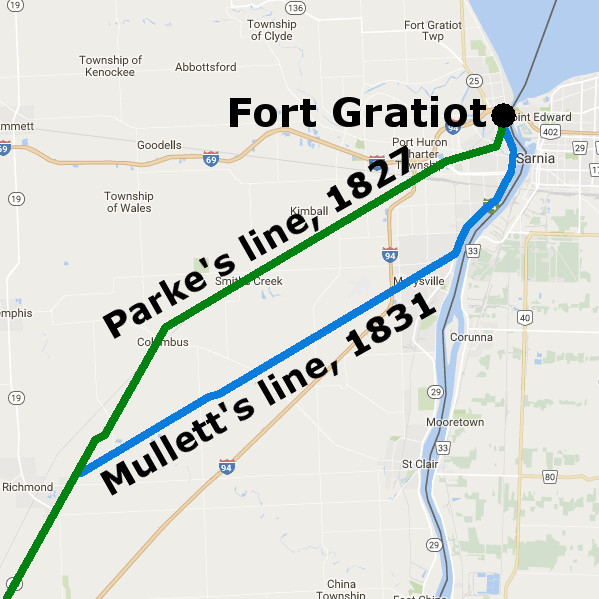

Re-Routing

The swamps and fallen timber along the final miles of the route weren't just a problem for the surveyors in 1827. They also caused Major Whiting to doubt whether this was the best location for the road itself. In 1831, he suggested to Col. Gratiot that a better path be found. Later that year, surveyor John Mullett was hired to do just that. Beginning at Parke's thirty-seventh mile post, Mullett's new line immediately turned toward the St. Clair River. The line then follows the riverbank up to Fort Gratiot.

Col. Gratiot's annual report for 1831 noted that, although work on the road had been contracted for up to the thirty-ninth mile,

at this point it was thought advisable to suspend the operations for a short time, in order to have a survey made of a route which the superintendent thought would prove more eligible than the adopted one--an anticipation which is confirmed by the result of the survey; and it is therefore recommended that authority of law to make the proposed change of location be requested. The construction of the road on the new route will be attended with less expense, and will open access to a finer country than that bordering on the adopted route.Lewis Cass, who by then had been appointed as Secretary of War, endorsed the plan and asked Austin Wing for congressional approval. When the next appropriation bill for the road was passed on July 3, 1832, it included a clause granting Cass the authority to make the change. Another $15,000 was also granted to continue its construction.

Col. Gratiot's report for 1832 stated that the available funds should be sufficient to finish the road, and no appropriation was made in 1833. The Fort Gratiot Road was completed by the end of 1834.

Gratiot Avenue Over the Years

The foot of Gratiot Avenue in downtown Detroit, circa 1915.

Image courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. (Source.)

Gratiot Avenue did not give rise to as many taverns, stagecoach stops, and settlements as did the Chicago Road, but there were few. One such tavern, built around 1840, was the Four Mile House, formerly located at 8806 Gratiot Avenue. It was converted into a private residence in the 1860s and demolished in 1938.

The Four Mile House, undergoing demolition.

Image courtesy Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. (Source.)

Travelers of the early 19th century could also have found accommodations at the Half Way House, so called because it was at the midpoint between Detroit and Mount Clemens. Located at what is now the southwest corner of Gratiot Avenue and Nine Mile Road, the settlement that grew up around it became known as "Halfway," even retaining that name when incorporating as a village in 1924. But when this village became a city in 1929, it adopted the name East Detroit.

The "Halfway House" Tavern, in what is now Eastpointe.

Image courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. (Source)

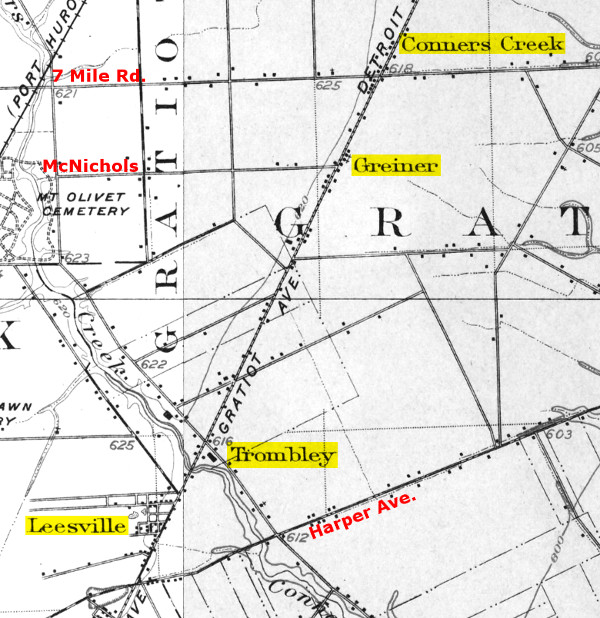

As late as the early 20th century, Gratiot Avenue was just a rural country road beyond Harper Avenue. Several unincorporated communities sprung up along its path, including Leesville, Trombley, Grenier, and Conner's Creek. Every one of these rural hamlets have since been incorporated into the City of Detroit.

Gratiot Ave., between Harper Ave. and 8 Mile Rd., 1905.

Maps courtesy USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer. (Source.)

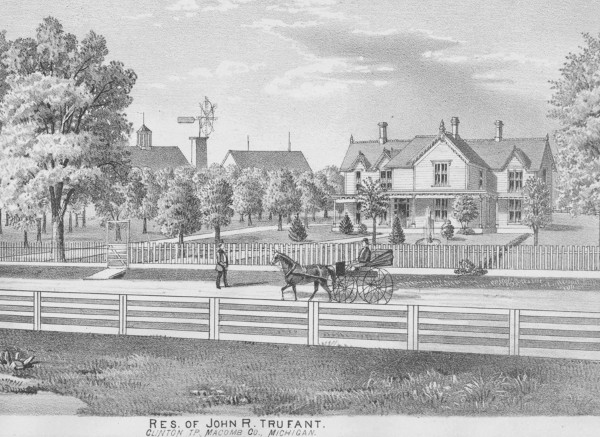

The Trufant Farm in Clinton Township, 1875. This depicts the west side of Gratiot, one half mile north of 16 Mile Rd. (Source.)

Gratiot Ave. in Mt. Clemens, circa 1910.

Image courtesy Suburban Library Cooperative. (Source.)

In 1915, Chicago architect Edward H. Bennett was hired to advise the Detroit City Plan commission on improving the city. Among his recommendations was extending Monroe Avenue at an angle to connect to Gratiot Avenue. Traffic congestion finally forced the city to decide whether or not to follow this recommendation in 1936, but the city council chose to widen Gratiot Avenue and Randolph Street, maintaining the zig-zag path drivers must take when heading northeast from the center of the city.

Detail from Edward Bennett's recommendations for the Detroit City Plan. (Source.)

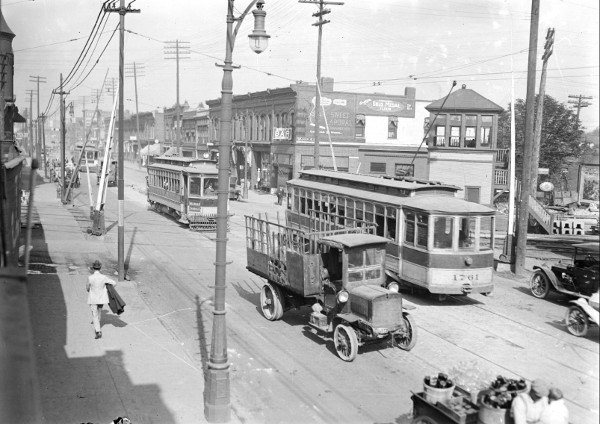

Gratiot Ave. at Dequindre St. in Detroit, circa 1920.

Image courtesy Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. (Source.)

Gratiot Ave. in Roseville, 1924. Interurban streetcar tracks once paralleled the entire length of Gratiot Ave., from Detroit to Port Huron, from 1899 to 1930. Service continued to Mount Clemens until 1932.

Image courtesy Suburban Library Cooperative. (Source.)

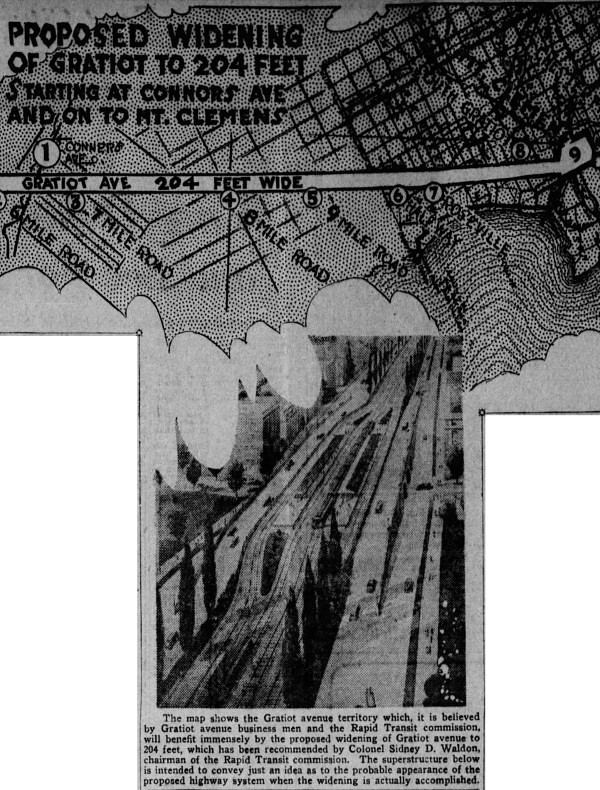

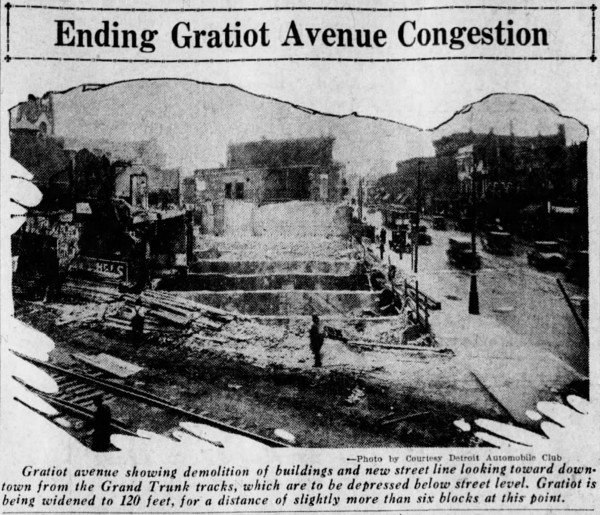

In 1924, the Detroit Rapid Transit Commission proposed a system of superhighways for the metropolitan region, with the intention of carrying not just automobile traffic, but passenger rail lines as well. The commission recommended widening arterial roads to 120 feet wide in urban areas and 204 feet in the suburbs. Over the next twelve years, Gratiot Avenue within the City of Detroit was expanded to widths ranging from 120 to 129 feet. North of Eight Mile Road, the right-of-way was widened to 204 feet. The first widening of Gratiot Avenue in Mount Clemens occurred in 1933.

Source: Detroit Free Press, April 13, 1924.

Source: Detroit Free Press, July 8, 1928.

Once the road widenings were complete, Gratiot Avenue more or less became what it is today. I'd like to close this post with a few photos of Gratiot Avenue icons that you might recognize if you grew up on the east side.

Gratiot Ave. in Roseville, circa 1930s. The two-story building is still standing, and now houses Paul's Bike Depot, 28057 Gratiot.

Image courtesy Suburban Library Cooperative. (Source.)

The Gratiot Drive-In, built in Roseville in 1948, featured a three-story waterfall on the reverse side of its projection screen. The waterfall was shut off in the 1960s, and the structure ultimately demolished in 1984.

Image courtesy SeekingMichigan.org. (Source.)

Better Made Potato Chips, in business since the 1920s,

moved to 10148 Gratiot by 1949. (Source.)

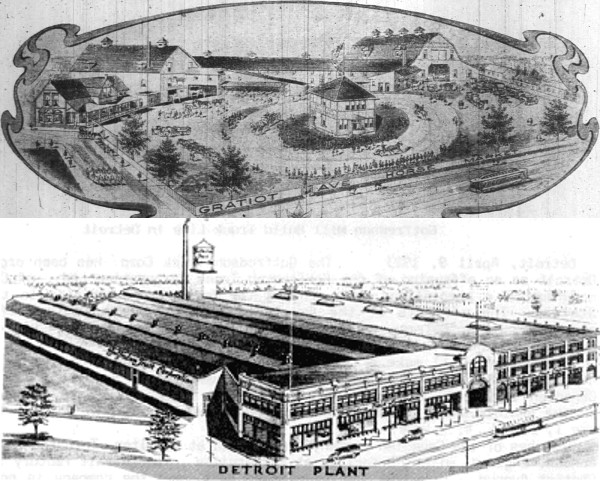

Top: The Kolb-Gotfredson Company's horse market on the west side of Gratiot, north of Leland Street, as it appeared in 1905. (Source.)

Bottom: Kolb-Gotfredson's truck factory, circa 1920s, built in stages on the site of the former horse market. In 1935 the building was purchased by the Feigenson Brothers Company, bottlers of Faygo. Faygo has been made here ever since. (Source.)

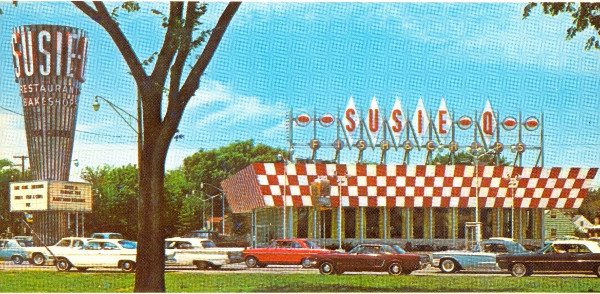

Susie-Q Restaurant, 27027 Gratiot, opened in 1964. Its iconic rotating metal tower was later associated with Arthur Treacher's Fish & Chips, Dmitri's, and National Coney Island.

Image courtesy Roseville History Archive.

John and Patricia Pioszak opened the Plum Pit, a retail store specializing in hippie clothing and paraphernalia, in 1967. (Source.)

Originally opened as the Eastwood Theatre in the 1940s, this building at 21145 Gratiot housed the Wired Frog Cafe from 1997-2004. (Source.)

Macomb Mall was built in 1964 on the former Mulso farm in Roseville. Since this photo was taken in 2006, this iconic neon sign has been replaced with back-lit plastic panels.

Photo from wayitwas.us by user phil101. (Source.)

Interesting description of French/American influence in this area

ReplyDeleteI recently moved to Detroit’s Eastern Market. I love watching and listening to Gratiot below my window. I am especially interested in what was in my area when the Native Americans had this land, long before I-375, and before Gratiot.

ReplyDeleteAre you ever available to meet in-person and walk this area with a coffee and to give a newcomer a historic talk?

You Do Excellent Work On Your Blog. I visited this website every day. Thanks and keep it up. doramas online

ReplyDeleteGreat article! Could you expand on a few points: Why does the CN/GTW railroad follow Parke's line and not Mullett's? When was Gratiot turned into a plank road? Did it have tolls? When was it paved? Diverted in Mt Clemens?

ReplyDelete