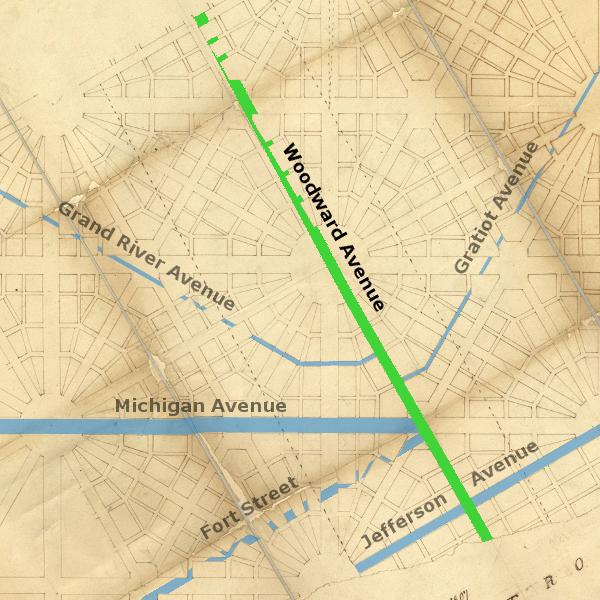

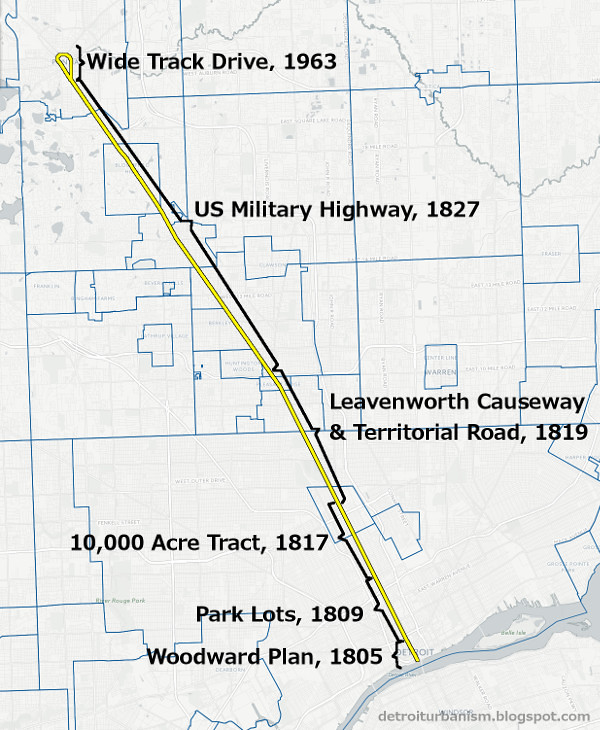

Woodward Avenue was born with the passage of "An act concerning highways and roads" on September 18, 1805. Along with Jefferson Avenue, it was the first road created by Michigan's territorial government following the great Detroit fire of June 11, 1805. Although the Woodward Plan could not yet be made law, its main principles had been worked out by this time and these two roads were established in anticipation of it.

Woodward Avenue, as originally established by this law, ran one mile inland from the Detroit River, heading north, thirty degrees west. However, no maps, laws, or other documents predating the War of 1812 refer to the avenue as "Woodward." One name adopted early on was Court House Avenue, when the plan at the time was to build the State Court House at the center of the Grand Circus.

The Saginaw Trail

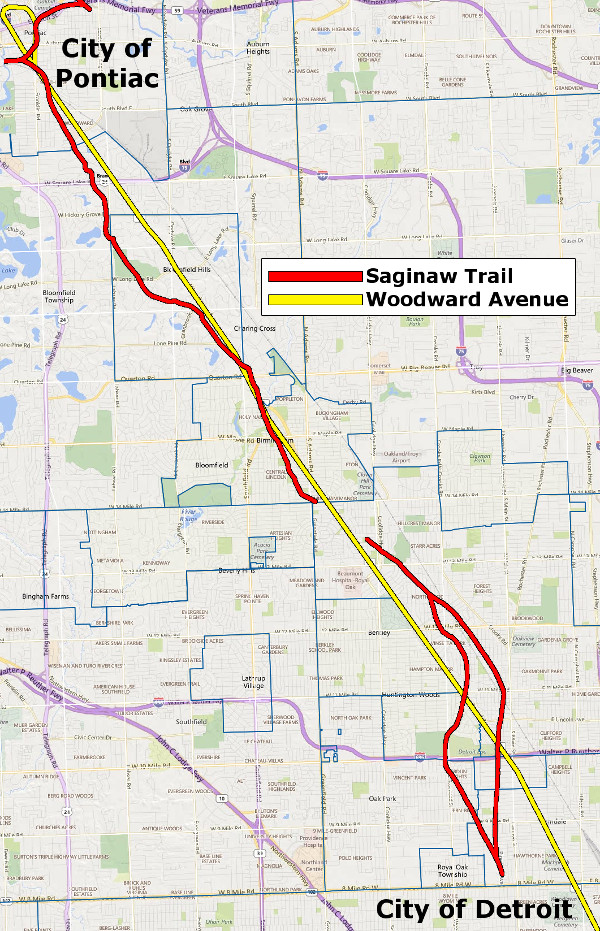

Before the existence of Woodward Avenue, overland travelers to Oakland County and beyond utilized the Saginaw Trail, which led to the Saginaw River of Lake Huron. This ancient footpath had a profound effect on the development of Woodward Avenue and Metro Detroit.

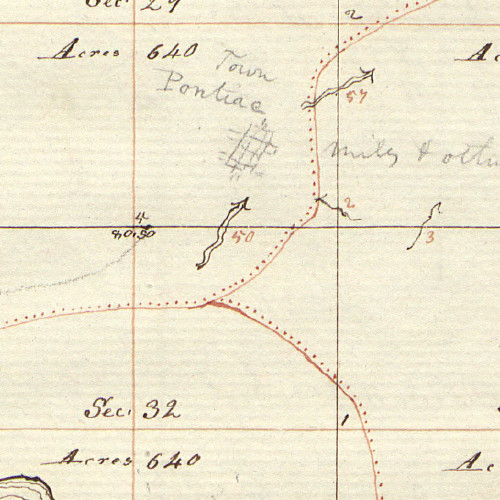

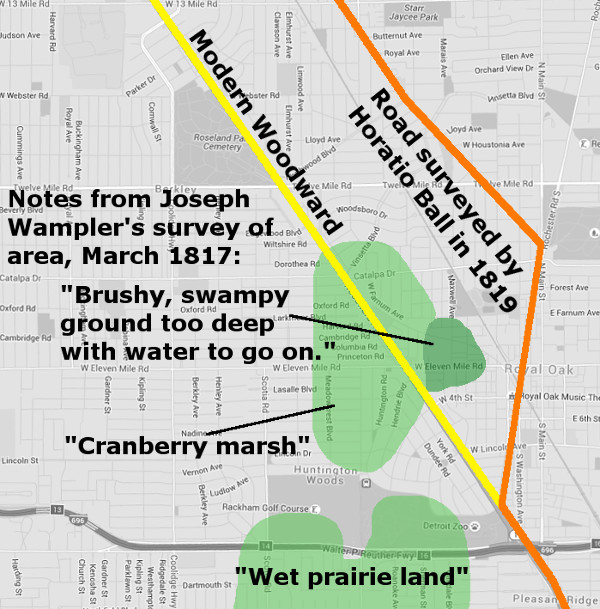

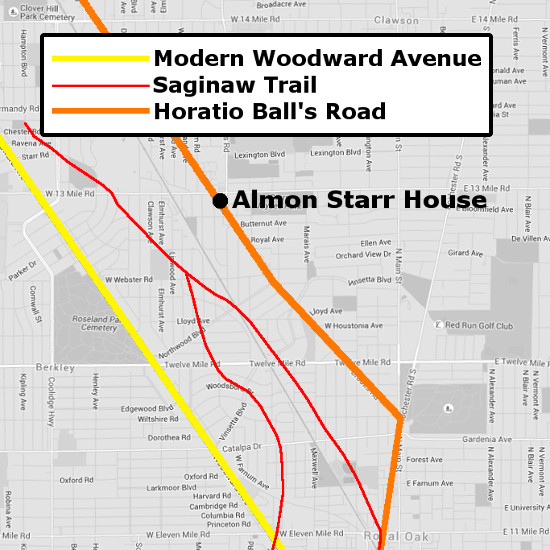

The path of the Saginaw Trail through southeastern Oakland

County, as documented by surveyor Joseph Wampler in 1817.

For example, when a group of pioneers from Detroit set out to establish the first white settlement in Oakland County, they chose the spot where the Saginaw Trail crossed the Clinton River. The settlement, established in 1818, would become the City of Pontiac. Although Woodward Avenue was destined to connect these two cities on the Saginaw Trail, very little if any of the road was built on exactly the same path. Instead, Woodward Avenue became a straight and direct alternative to the trail, replacing it in stages over time.

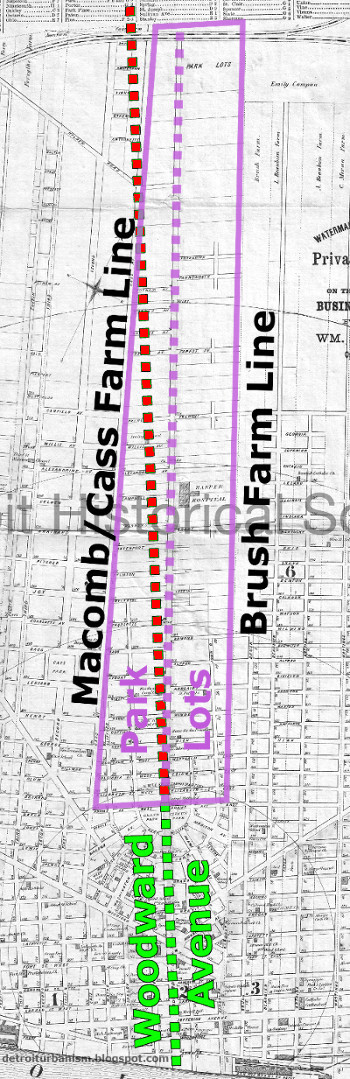

The Park Lots & 10,000 Acre Tract

When today's Woodward Avenue meets Grand Circus Park, it makes a four-degree turn to the north. Not one foot of the road north of Adams Avenue truly follows the Woodward Plan. The reason for this deviation has to do with a large donation of federal land to the Michigan Territory, and how it was divided up for sale.

In 1806, Congress granted ten thousand acres of federal land to the Michigan territorial government to fund the construction of a courthouse and a jail. This land was surveyed in two sections, the first being known as the Park Lots, and the second called the Ten Thousand Acre Tract.

The Park Lots were located just north of Adams Avenue, in the long, narrow space between the Macomb and Brush farms. The land was surveyed into two tiers of lots in 1809. In order to maintain some uniformity in lot sizes, the line dividing the two tiers was kept parallel to the border of the Brush farm. This was a problem. When Woodward Avenue was extended northward, it followed this line parallel to the Brush farm in the direction north, twenty-six degrees west. But according to the Woodward Plan, the avenue should have followed a course north, thirty degrees west.

The Park Lots (in purple) with original Woodward Avenue (in green), where it should lie beyond the Grand Circus (in red), and where it was actually built (in purple).

Judge Woodward complained about this divergence from his plan, writing, "When the deviation from a direct course in the avenue leading from the strait to the forest was originally made, an angle awkwardly and injudiciously placed in the course of the communication, and the width reduced to sixty feet, it was done, as I understand, to gratify [Judge] James Witherell." To add insult to injury, the road north of the Grand Circus was for many years known as Witherell Street.

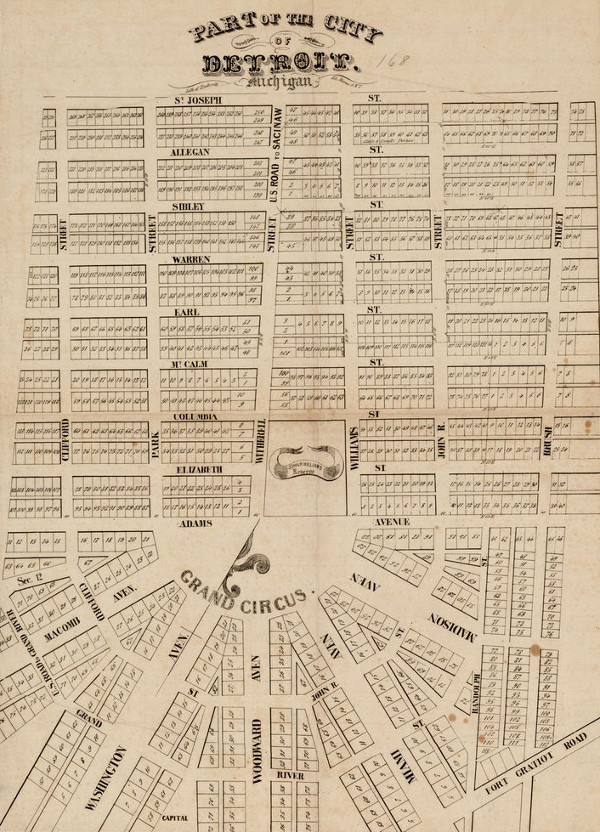

A circa 1835 map of the vicinity of Witherell St./Woodward Ave.

Image courtesy RareMaps.com (Source.)

When the Ten Thousand Acre Tract was surveyed in 1817, a right-of-way was reserved especially for an extension of "Witherell Street." As with the Park Lots, the assigned course was north, twenty-six degrees west. This right-of-way ended on the north border of the tract, at what is now the intersection of Woodward Avenue and Sears Street in Highland Park, six miles from the Detroit River.

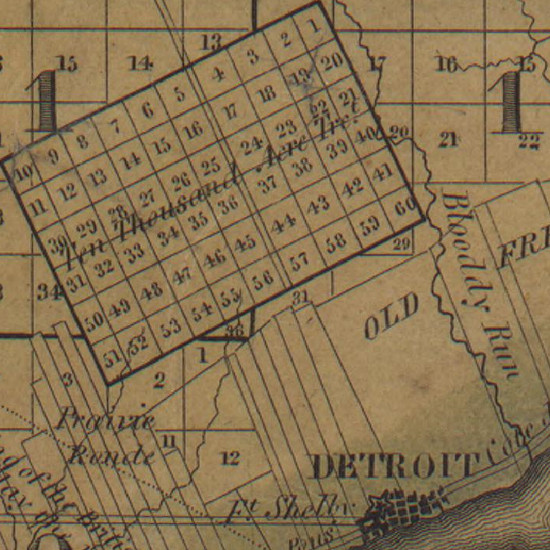

The Ten Thousand Acre Tract, bisected by Woodward Avenue, in 1826.

Detail from Orange Risdon's map of Michigan Territory. (Source.)

The Mack & Conant Turnpike

and the Leavenworth Causeway

As mentioned earlier, the settlement that would one day become the City of Pontiac was established where the Saginaw Trail met the Clinton River. A group of Detroit businessmen founded The Pontiac Company for the purpose of establishing this town in November 1818, purchasing US government land at the chosen site. The first settlers arrived before the end of that year.

Detail from surveyor Joseph Wampler's 1817 plat of the Pontiac area, with the settlement penciled in at a later date. The red lines represent Indian paths.

Image courtesy Bureau of Land Management, General Land Office.

Eager to attract settlers to Michigan's interior, the territorial government passed "An act to establish a certain road" on December 7, 1818. The law empowered the governor "to lay out and make a public highway and road, commencing at the center of the military square" (referring to Campus Martius), following the extant paths of Woodward Avenue and Witherell Street, and "thence on such a course as shall be determined by three commissioners, or a majority of them, to be appointed for that purpose by the governor." Governor Lewis Cass appointed John Hunt, Ezra Baldwin, and Levi Cook as the commissioners who would determine the route beyond the Ten Thousand Acre Tract.

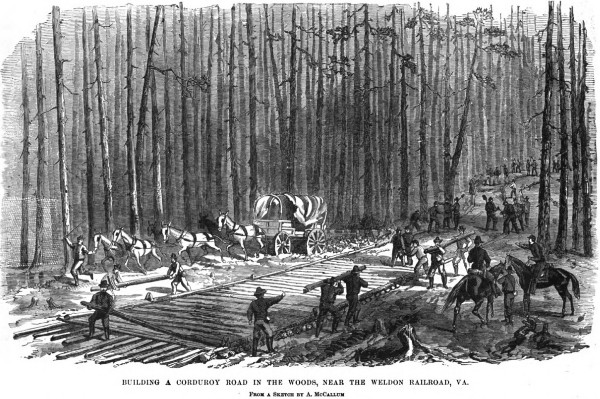

In the meantime, work began on the first portion of the road. John S. Roby was appointed superintendent of the project, and the mercantile firm Mack & Conant was contracted to build the road from Grand Circus through the end of the Ten Thousand Acre Tract. The proprietors of Mack & Conant were Major Stephen Mack and Shubael Conant. Mack was a founding member of the Pontiac Company. (Coincidentally Mack's nephew, Joseph Smith, was founder of the Church of Latter Day Saints.) Mack & Conant were paid $6,000 to construct the road, which was built on a foundation stabilized by logs laid across its path. This type of thoroughfare was commonly referred to as a corduroy road.

An 1860s depiction of corduroy road construction. (Source.)

The US government took responsibility for the continuation of the road beyond the Ten Thousand Acre Tract. The first few miles were constructed by US troops under the command of Colonel Henry Leavenworth of Fort Detroit. Work began at least as early as January 1819. The road continued in the same direction as it had since the Grand Circus: north, twenty-six degrees west.

Pioneer Edwin Jerome would later recall that Mack & Conant "built 5¾ miles of the present Detroit and Saginaw Turnpike, leading directly towards (an) impassable swamp." It was through this swamp that Leavenworth's troops attempted to continue the road, which here would be known as Leavenworth's Causeway. Surveyor Hervey Parke, who traversed the road in 1821, called this segment "the worst ever built, as no regard was had to equalizing the size of the logs--the largest and the smallest lying side by side."

The following item, printed in the November 10, 1820 edition of the Detroit Gazette, reported the progress on the new road to Pontiac:

The Pontiac Road.--The six miles of this important road, which Maj. S. Mack contracted to complete, and the progress of which our citizens have watched with so much interest, are now finished, and, we are happy to say, in a manner highly to the reputation of the contractor and the satisfaction of the public.--Considerably more than one half of the road made by Mr. Mack, is formed of very large logs, laid closely together, across the road, on which are piled small timber, brush, clay and sand, making a dry, and at the same time a durable highway. The principal obstacles encountered in making the road, were the immense number of large and small trees, with which the country immediately in the rear of this place abounds.Many of those who traveled to Oakland County by way of Detroit took Mack & Conant's turnpike part of the way and followed the Native American trail for the remainder of their journey. Mrs. Jane M. Palmer, who came to Detroit in 1820 at the age of twenty, recalled making the trip in those early days:

It is, we believe, admitted on all hands, that Maj. Mack has completed the most difficult part of the road between this place and Pontiac.--Still considerable labor remains to be done, for the track beyond the six miles does not deserve the name of road--we refer more particularly to the portion lying this side of the cranberry marsh, and that near Mr. Woodford's and beyond Mr. Thurber's.

Mrs. John P. Sheldon and myself, each with an infant in our arms, started to visit Mrs. Sheldon's father, who lived in Oakland county, twenty-eight miles from Detroit. We made the six miles over Mack & Conant's turnpike and twenty-two miles along an Indian trail in just two days. Rather slow, wasn't it?

The Cass Proclamation

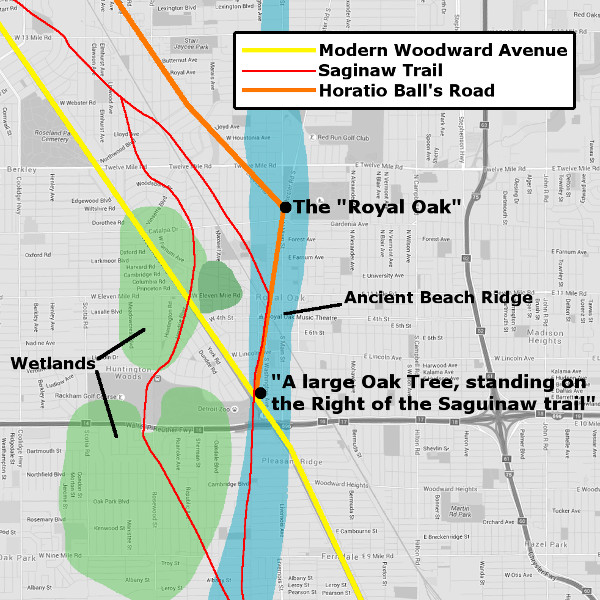

By the end of 1819, the road commissioners appointed by Governor Cass had completed their report on the planned road to Pontiac. Horatio Ball had been appointed surveyor of the Michigan Territory on July 17 of that year, and he assisted the commissioners in surveying the route. But the route they chose was not the Woodward Avenue we know today.

The commissioners' report was delivered to Cass on December 13, 1819. On December 15, Cass issued a proclamation, declaring much of what is now Woodward Avenue to be a public highway for the first time. The document outlined the route in the following way:

I do lay out the following, as a public Road or Highway, namely:—commencing at the centre of the Military Square in Woodward Avenue in the City of Detroit, and Running thence along said Avenue to Witherell Street, and thence with Witherell Street to the commencement of the Space of one hundred feet between Lots numbered 56 and 57 in Fletcher's Plan of the Survey of the Tract of Land granted by the Act of Congress passed April 21, 1806... thence along said space of one hundred feet and with the course thereof, through the said tract;—thence westwardly on the Road which was opened and cut by the Troops of the United States, to the termination thereof; thence westwardly to a large Oak Tree, standing on the Right of the Saguinaw [sic] trail so called, and within a short distance of the same, the said Tree being marked with the Letter H. Thence westwardly in a direct Line as surveyed and marked by Horatio Ball to the Main Street in the Village of Pontiac, and thence along said Street to its termination.In other words, the road began at the Point of Origin in Campus Martius, ran up Woodward Avenue to the center of the Grand Circus, followed "Witherell Street" up through the Park Lots and Ten Thousand Acre Tract, and continued along the Leavenworth Causeway. This follows present-day Woodward Avenue for just over eleven miles, but it departs from today's road, zig-zagging through what is now Royal Oak, as seen in Orange Risdon's 1826 map:

To understand why this detour was made, one needs to look at the topography of Royal Oak at the time.

Swamps, Marshes, & the "Pleasant Ridge"

When surveyor Joseph Wampler subdivided the township later known as Royal Oak into one-mile sections in March 1817, he recorded in his field notes the locations of swampy and marshy areas. When Wampler's data are superimposed over a modern map, we can see that continuing Woodward Avenue on a straight line would have run it straight into a cranberry marsh. The territorial government was eager to establish overland travel into Oakland County, but it was not yet practical to drain the wetlands or build a substantial causeway through them.

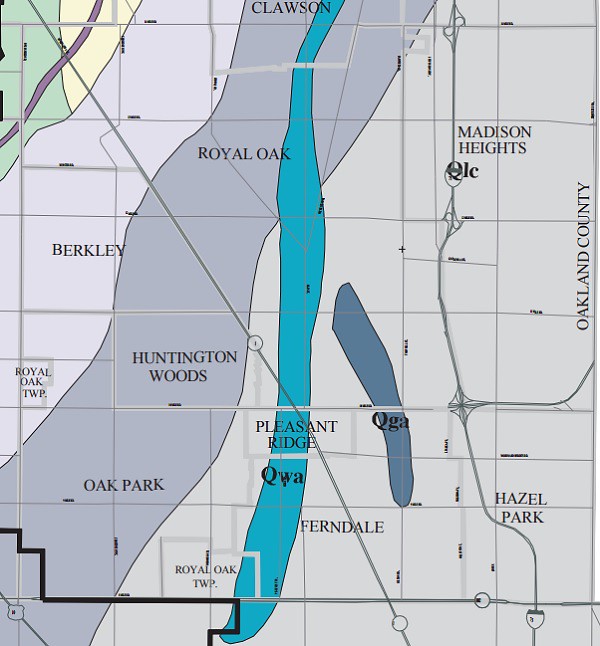

Fortunately, Royal Oak wasn't all swampland. There was also a ridge of high, well-drained ground that runs north through the area. This is an ancient beach ridge, formed 13,000 years ago when this was the shore of Lake Wayne, an ancient great lake that encompassed what is now Lakes Erie and St. Clair. This ridge is what gives Pinecrest Drive, Ridge Road, and the City of Pleasant Ridge their names.

The ancient beach ridge formed by Lake Wayne, shown in light blue. (Source.)

When the road surveyed by Horatio Ball made an abrupt turn to the north, it followed this ridge to bypass the cranberry marsh. The older Saginaw Trail took the same route, naturally avoiding areas prone to flooding. In fact, Ball's road coincided with the Saginaw Trail for a short distance, now preserved as Lafayette Avenue. This bend in the road, as noted in Cass' proclamation, was marked by "a large Oak Tree, standing on the Right of the Saguinaw trail."

When approaching Lafayette Avenue in Royal Oak today, it's easy to see that it follows the crest of the prehistoric beach ridge. The photographs below were taken while facing Lafayette Avenue at a ninety degree angle.

The Royal Oak

The original road continued along the ridge to a second large oak tree, once located close to the present-day intersection of Main Street and Crooks Road. Horatio Ball marked this tree with a letter H, and from this point surveyed the remainder of the road, leading northwest to Pontiac.

The tree marked by Horatio Ball's initial became an important landmark, as pioneer Thomas J. Drake recalled in 1872:

The tree was of some magnitude, and, after the issuing of the proclamation, became an object of observation and was called, by way of distinction, the "Royal Oak," and soon the name of Royal Oak was applied to that portion of the country, and was given to the town at its organization.An apocryphal story later developed in which it was Lewis Cass who personally gave the tree its name. Cass allegedly stopped at this spot during an expedition and, being reminded of the legend of the future King Charles II hiding from his enemies in the branches of a large oak, bestowed the tree with the same name as the one in the English legend.

The Royal Oak is now gone, but a plaque has been placed not far from where it once stood.

With an understanding of the early topography and landmarks of Royal Oak, we can now see where and why the "original" Woodward Avenue described in Cass' 1819 proclamation used to lie.

Ball Line Road

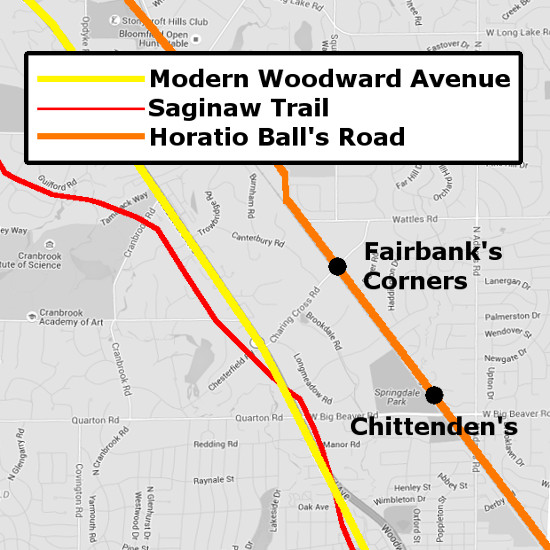

The road built on the line surveyed by Horatio Ball from the Royal Oak to Pontiac was known by early settlers as Ball Line Road. Sections of it survives as Crooks Road in Royal Oak and Kensington Road in Bloomfield Township.

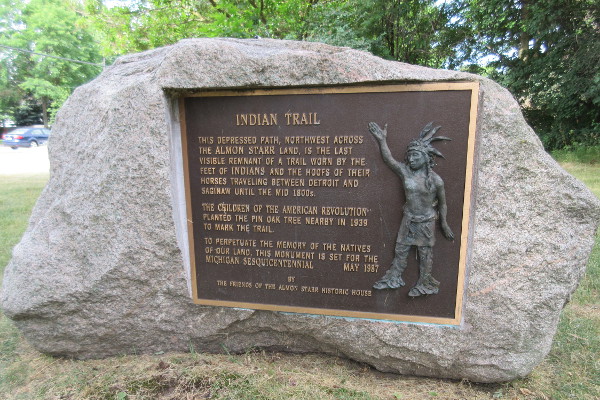

An early settler of Royal Oak, John Almon Starr, built a home close to Ball Line Road in 1868. The house is still there today, along with evidence that the road once crossed his property. The indentation in the earth seen in the photos below matches the former location of the road to Pontiac.

The depression in the earth lines up with Crooks Road.

A plaque on the site alleges that the road used to be part of the Saginaw Trail. However, the Indian paths recorded in Joseph Wampler's 1817 survey do not cross the Starr property, whereas the road surveyed by Horatio Ball certainly did.

Plaque at the Almon Starr House.

Woodward Avenue Continues

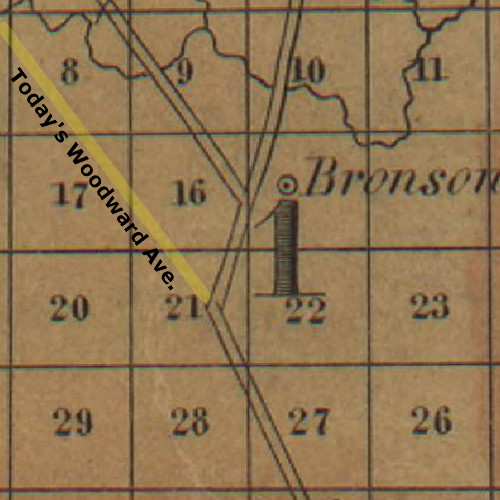

The road established by Cass' proclamation remained the chief route between Detroit and Pontiac for the better part of a decade. The first lodge and store for travelers to open in Royal Oak was that of Henry O. Bronson in 1822, located close to the Royal Oak tree. Small settlements were even started on the road, including Fairbank's Corners and Chittenden's, both in what is now Bloomfield Township.

The detour in Royal Oak was only temporary, and the federal government was ultimately determined to continue Woodward Avenue as a straight highway. An 1827 law authorized the President of the United States to appoint three commissioners to survey a road from Detroit to Saginaw. The appointed individuals were Ellis Doty, Davis McKinstry, and Linah Mims, whose report was submitted June 9, 1827. Congress paid for the survey, but did not yet fund any further construction. In December 1828, the House of Representatives asked the Secretary of War to report on the cost of completing the road to Saginaw as well as his opinion of its military importance. The report was made to Congress within a few weeks, supporting the completion of the road, and the legislature appropriated $10,000 "for completing the road from Detroit to Saganaw [sic]" on March 2, 1829. Brigadier General Charles Gratiot, Chief Engineer of the US Army, reported in November of that year, "The construction of fifteen miles and a quarter of this road has been contracted for and is in progress." In May of 1830, Congress approved an additional expenditure of $7,000 for the project. Gen. Gratiot's report for that year noted, "seventeen and a half miles (have) been completed, and contracts made for continuing the work to the end of the 1st quarter of the thirty-third mile," and Congress appropriated another $8,000 four months later. Finally, in 1831, it was reported that twenty-seven miles of the road had been finished. There was much more work to be done before the road would reach Saginaw, but the portion connecting Detroit and Pontiac--what is today designated as Woodward Avenue--was complete.

Ball Line Road Bypassed

The completion of the military highway to Pontiac left Oakland County with two roads connecting Pontiac and Royal Oak. The two intersected about one and a half miles southeast of Pontiac.

Orrin Poppleton, an early Oakland County resident who opened a mercantile business in what is now Birmingham in 1840, wrote about the events that led to one road becoming a major arterial highway and the other virtually dying off. He described Fairbanks and Chittendens, the villages on the Ball Line Road, as having bright futures, offering serious competition to Birmingham, which was then called Hamilton's. Poppleton wrote:

When a mail route was about to be established, each proposed route or road had its advocates and promoters. Men who were interested in each, circulated petitions to the postmaster general, praying for the establishment of the expected mail route on each one's favorite road. The strife and heat of the petitioners waxed warm but the influences brought to bear upon the authorities at Washington were strongest in favor of the territorial road [Woodward Avenue]. The mail was then ordered carried by way of Hamilton's on that route. From that date Fairbanks and Chittendens began to decline, and many years ago there disappeared the last vestige of what once promised to be lively manufacturing towns. Had the influences at Washington been strongest in favor of the Ball line and had the mail route been established on that road there would have been no Birmingham here.Samuel Durant's 1877 History of Oakland County notes that Talbot's tavern in Royal Oak, located on Ball Line Road, "enjoyed a season of comparative prosperity so long as the travel continued to pass by its doors," but the establishment was "ruined by the opening of the Saginaw or Detroit and Pontiac road, which carried the travel away from it, over a new route."

Modern Alterations

Woodward Avenue near Seven Mile Road in 1915, at a fraction of its current width.

Image courtesy Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University. (Source.)

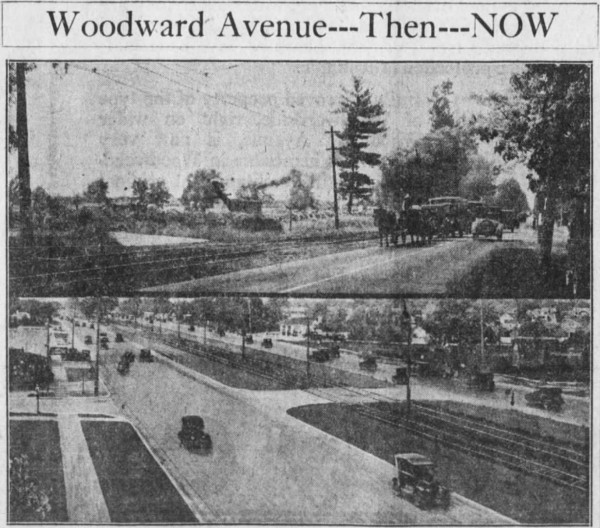

In November 1921, a group of civic and business leaders founded the Wider Woodward Avenue Association, a nonprofit corporation whose goals were to increase public support of widening the road, lobbying for legislation to fund the project, and obtaining the necessary land where it could be purchased. Woodward Avenue from Six Mile Road to Pontiac would ultimately be expanded to the standardized "superhighway" right-of-way (including driving lanes, medians, sidewalks, etc.) of 204 feet.

Before and after the widening in the Royal Oak area.

Source: Detroit Free Press, 22 Jan. 1928.

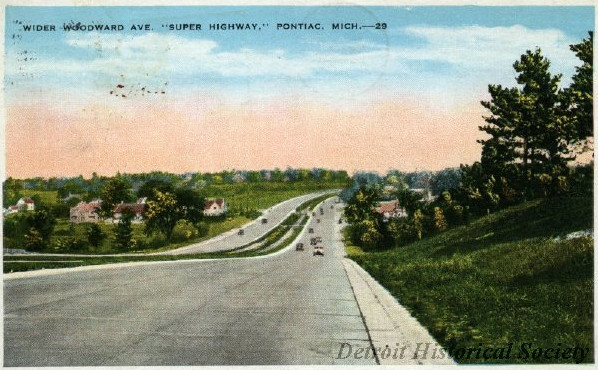

A 1931 postcard depicting the newly widened Woodard Ave. near Pontiac.

Image courtesy Detroit Historical society. (Source.)

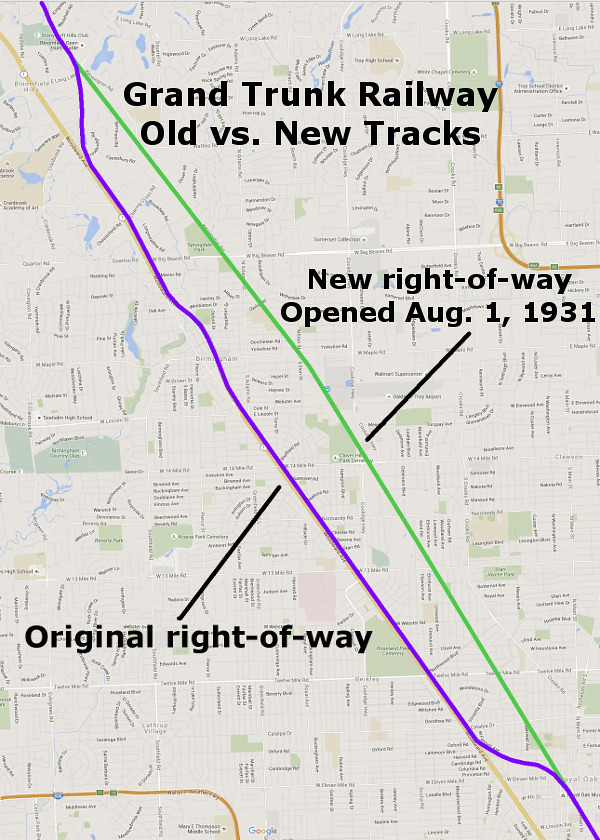

From Catalpa Drive in Royal Oak to Lone Pine Road in Bloomfield Hills, Woodward Avenue expanded by incorporating the Grand Trunk Railway right-of-way that ran parallel to it. The State of Michigan granted the railroad a new right-of-way approximately one mile to the east, in some parts following the former Ball Line Road. Commuter service began over the new Grand Trunk lines on August 1, 1931.

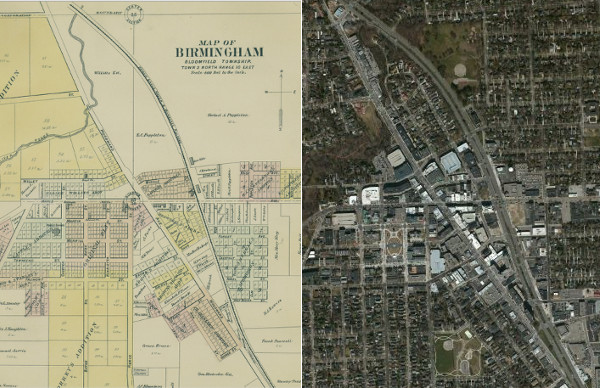

In areas where the original Grand Trunk Railway lines did not run adjacent to the road, the widening project entailed the condemnation of property along Woodward Avenue. Fortunately for Birmingham, the Grant Trunk Railway did not run through the center of the municipality, but bypassed it to the east. When the railroad tracks were removed, the right-of-way was paved over and transformed into Hunter Boulevard. The opening of this bypass on November 3, 1939, marked the completion of the Wider Woodward Avenue project. The name of this bypass changed from Hunter Boulevard to Woodward Avenue on September 6, 1997, and the former Woodward Avenue through downtown Birmingham was renamed Old Woodward Avenue.

Birmingham in 1896 and today. The "new" Woodward Avenue was built on what had been a railroad right-of-way since 1839. (Source)

Downtown Detroit also saw changes in the late 1950s. Woodward Avenue was widened by seventy feet south of Campus Martius and closed off completely south of Jefferson Avenue as part of the Civic Center urban renewal project.

Within the City of Pontiac, Woodward Avenue had long been called Saginaw Street. In the 1960s, all Saginaw Street traffic was forced onto a new, four-lane, one-way loop which cut off downtown from the rest of the city. It was completed in 1964 and named Wide Track Drive, after a General Motors marketing slogan. One urban planner has called this road "a metaphorical noose choking the life out of the downtown." Making matters worse, Saginaw Street was cut off just within the loop in the 1980s by the construction of the Phoenix Center, ensuring that traffic would be permanently diverted from the central business district.

Downtown Pontiac in 1940 and in 2015.

On September 5, 2000, Pontiac's Wide Track Drive loop and the portion of Saginaw Street south of it were renamed Woodward Avenue, finally uniting the twenty-seven miles of road that we recognize as a continuous avenue today.

From its beginning as one of the first two roads laid out by Judge Woodward after the fire of 1805, and its extension as the first highway into Michigan's interior, Woodward Avenue has remained the region's Main Street and an icon of Metropolitan Detroit's history.

Excellent writing and interesting history. Thanks for making the effort.

ReplyDeleteWhat do you think of "Spirit Plaza" at Woodward and Jefferson?

ReplyDeleteI know drivers were upset about having to take alternate routes to Jefferson, but I do like that the city is working to connect Campus Martius with the riverfront by making more places for people. What's there now was temporary and experimental, and it kind of looks that way. Now that it's supposed to become permanent, I hope the look and setup can be improved a little.

Delete