Source: Trafficways for 3 Million People, Detroit City Plan Commission, 1954.

Although the Woodward Plan was designed to be an indefinitely repeatable pattern, it never covered more than half of one square mile. Even within this area, it has been infringed and even removed. This article explores why the plan never expanded and how these disruptions came to be.

The Park Lots & Ten Thousand Acre Tract

The 1806 law that allowed the governor and judges to lay out a new town also directed them to sell 10,000 acres of adjacent land owned by the U.S. government in order to fund the construction of a court house and a jail. The first area to be sold was the narrow strip of land north of the town lying between the Brush and Cass farms. It was divided into lots ranging from five to ten acres.

These lots, which came to be known as the Park Lots, were auctioned off in 1809. When deeds were finally issued (some as late as 1816), Judge Woodward added the proviso "the City of Detroit may extend over [the lots], without [the owner] expecting or claiming any compensation for the avenues, streets, roads, alleys, lanes, squares, circuses and other public spaces and reservations of ground of the said City of Detroit according to the original plan thereof." The Woodward Plan wasn't technically defeated, but this proviso hardly guaranteed its northward expansion.

Then in late 1817, the governor and judges resolved to sell the rest of the 10,000 acres, which had been surveyed into farms containing roughly 160 acres each in a large rectangle known as the Ten Thousand Acre Tract. The farms were set to be auctioned on June 1, 1818.

Woodward wrote a long and detailed protest against the sale, knowing that his plan could never extend into parcels completely at odds with it. His arguments included:

- Federal law specifically authorized the governor and judges to lay out a town. The disposal of the land into large farming tracts was illegal.

- Territorial law established the Woodward Plan as the basis for Detroit, and dividing land into 160-acre parcels contrary to the plan was a violation of the law.

- The plan sent to Congress in late 1806 clearly showed Woodward's system extending far north of the Grand Circus, and to deviate from the plan was an "unlawful assumption of power."

Nature has destined the city of Detroit to be a great interior emporium, equal, if not superior, to any other on the surface of the terraqueous globe.... In such a case the art of man should aid the benevolence of the Creator, and no restricted attachment to the present day or to present interests, should induce a permanent sacrifice of ulterior and brilliant prospects. ...Woodward even offered a compromise: It so happened that it was possible to divide the land into rectangles containing approximately 160 acres in such a way that would conveniently accommodate the Plan of Detroit. Let the farmers farm, Woodward proposed, but on the the condition that they let the streets, avenues, plazas, etc. run through their land when the city reaches them. Woodward even offered to pay the estimated $300 to resurvey the ten thousand acre tract accordingly.

None of the great cities of Europe,--Lisbon, Paris, London, Dublin, Moscow,--can boast an antiquity (of more than) eight centuries, to the period when their magnitude, resources and accommodations were inferior to those of the present city of Detroit. If then in that period, of some in less, they have grown to their present opulence, splendor and celebrity, what may not the same period, prospectively regarded, bring about with respect to the city of Detroit, with superior natural advantages to any of these, and under a government more free, and (ten) times more enlightened? In half that period, it is not possible to assert not within one fourth of it, this phoenix of the world, now rising from the ashes of its parents, may transcend the present glories of those great and celebrated marts.

It was not to be. Woodward's protest was ignored, and the sale was held as planned. The Woodward Plan never extended north of the center line of Adams Avenue. In fact, Adams Avenue was never built to its planned width of 120 feet, but remains only sixty feet wide.

The Military Reserve

When the territorial government was empowered to lay out a new town in 1806, an exception was made for the land surrounding the fort. This land remained property of the U.S. government until an improved fort could be constructed elsewhere.

The Military Reserve at Detroit.

Image courtesy Library of Congress. (Source.)

On May 26, 1824, Congress granted a small part of the Military Reserve to the city, including Larned Street and the lots on its south side, between Griswold and Wayne Streets. There were no violations to the Woodward Plan in this area.

The City of Detroit petitioned Congress in January 1826, stating that the large quantity of ammunition stored on the Military Reserve was a "danger to the safety of the city and the lives of its inhabitants." The city asked that the military operations be moved farther away, and inquired whether the city could obtain the vacated land afterward. As a result, President John Q. Adams signed a bill on May 20, 1826 that granted most of the Military Reserve to the City of Detroit.

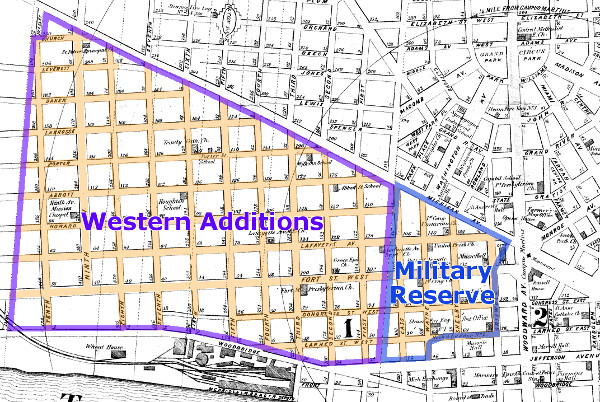

The city saw this acquisition as an opportunity to abandon the Woodward Plan once and for all. Although the city council was still bound by territorial law to follow the triangular system, on December 16, 1826 it unanimously adopted a resolution to petition the territorial legislature for the power to alter the city plan in any manner it chooses. The legislature complied, passing "An act relative to the City of Detroit" on April 4, 1827. The city was now free to redraw the map at will.

This law didn't simply apply to the Military Reserve--it permitted the city to scrap the entire plan north of Larned Street. The City Council had the power to condemn all property north of Larned Street--including lots that had been privately owned for more than twenty years--and to lay out an entirely new street grid, either paying the owners of the condemned lots or reassigning them a lot on the new plan. "A project was started, to alter the whole plan of the City, so as to establish it uniformly at right Angles," wrote Mayor John R. Williams in 1831. "This project (was) in the origin a wise and acceptable one."

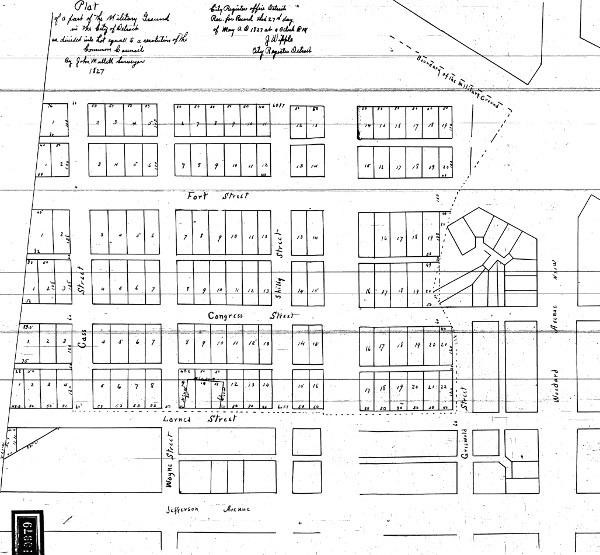

The city wasted no time. An auction of lots on the Military Reserve was advertised just days after the passage of the law, even before a plat was completed. Surveyor John Mullett drew plan of the Military Reserve, divided according to the new gridiron system and submitted it to the Wayne County Register in May of 1827. The auction was held on May 14, 1827 at Military Hall.

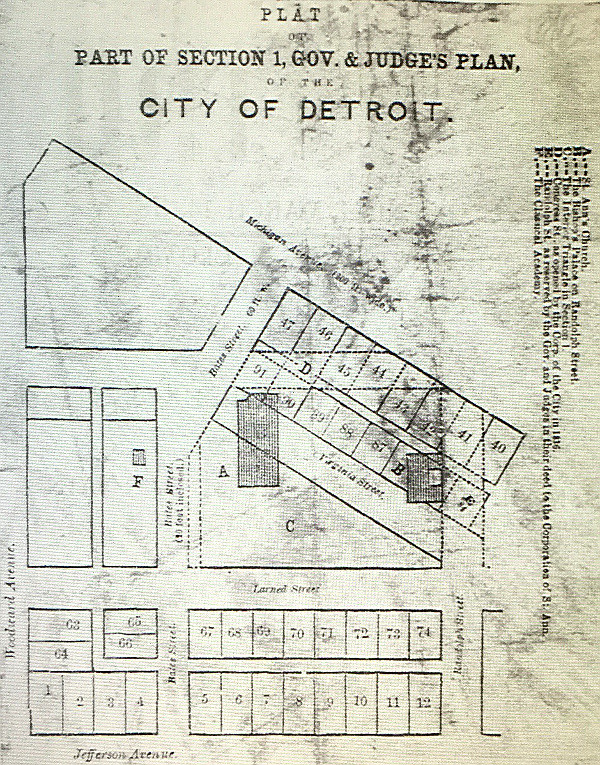

John Mullett's plat of the Military Reserve, 1827. (Source.)

The portion between Lafayette and Michigan Avenues was not platted right away, perhaps because the city planned to remove Michigan Avenue, which did not conform to the new grid.

Landowners in the city, alarmed at the city council's actions, petitioned Congress in January 1828, asking them to overturn the territorial law. The petitioners wrote:

[A]n ordinance ... has been passed vacating the recorded plan of the city of Detroit, and authorizing streets and alleys to be run, in directions entirely different, over the private property of your memorialists, throwing everything into the utmost confusion, and thereby impairing and destroying the property and rights of your memorialists without any kind of expediency or necessity for the public good, but merely to gratify the whim and caprice of some men who pretend to have a great predilection to a rectangular plan, instead of the old plan, which is on the basis of an equilateral triangle.Apparently the issue was solved locally, without federal intervention. Mayor Williams later admitted that "great objections existed" against the new plan, "which became more and more obvious and plain as the subject was examined into." He added, "After much individual effort (and) public Meetings ... the project was upon public reflection abandoned as impracticable."

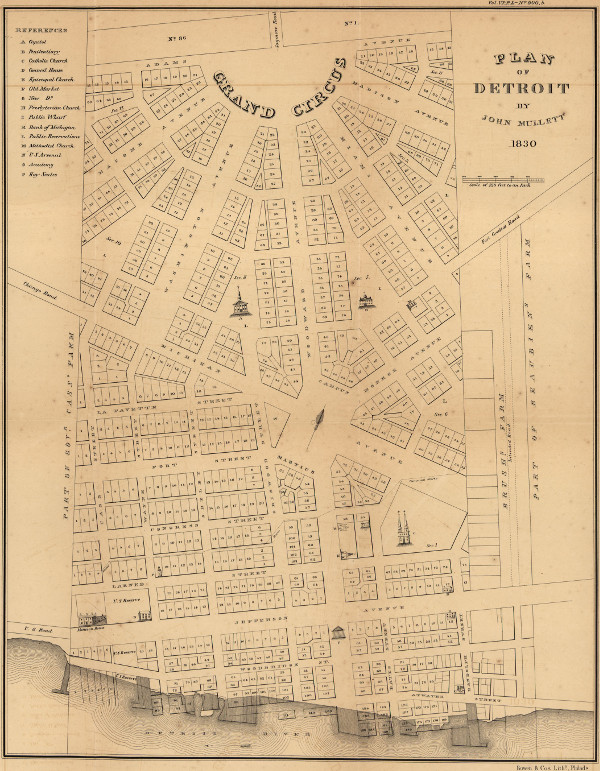

However, the gridiron system remained in place upon the former Military Reserve, a decision which Mayor Williams called "a sort of compromise" between the city and the owners of lots on the Woodward Plan. To this day, the southwest quadrant of downtown is divided into rectangular rather than triangular blocks.

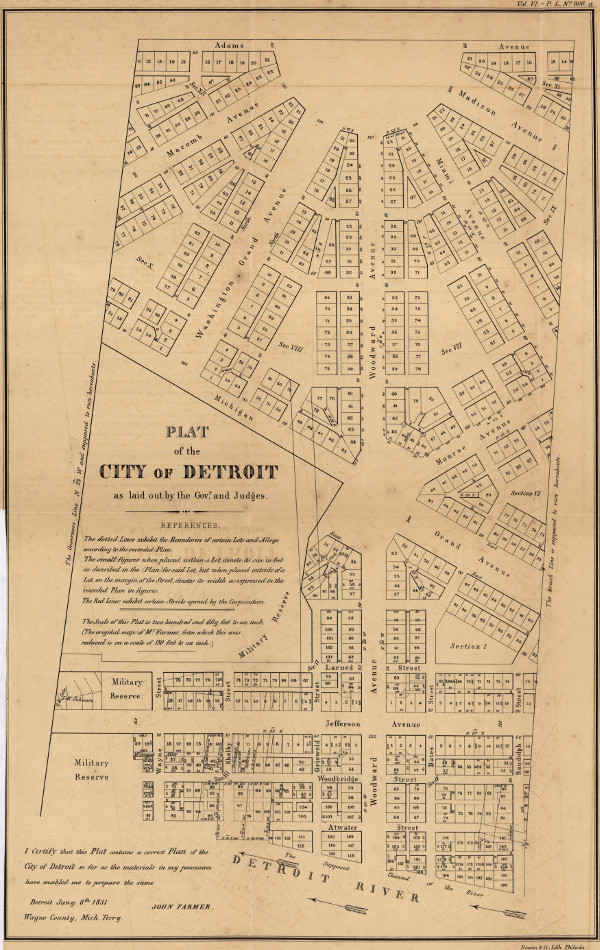

Plan of Detroit by John Mullett, 1830.

Image courtesy Library of Congress. (Source.)

Aside from the gridiron pattern in and of itself, this scheme also violates the Woodward Plan in that Michigan Avenue, like Adams Avenue, was only built to half of its intended width. Michigan Avenue should have been a continuation of Cadillac Square, a 200-foot-wide "grand avenue." Instead, the thoroughfare has a right-of-way of only 100 feet, and it used to narrow even further to sixty-six feet near Seventh Street.

As the city expanded westward in the 1830s, the Military Reserve gridiron was extended into what is now Corktown, covering all the land south of Michigan Avenue and east of Tenth Street. Parts of this grid have since been removed by the John C. Lodge Expressway and other urban renewal projects.

Although the Woodward Plan had been saved from being wiped out completely, the fact remained that as of 1827, it was no longer the official city plan. Not one more block would be laid out according to Woodward's formula.

A related violation of the Woodward Plan was the cutting through of Griswold Street across several lots in Sections 2 and 8. This connected the river to the territorial capitol building that was to be built at the center of Section 8.

Plan of Detroit by John Farmer, 1831.

Image courtesy Library of Congress. (Source.)

St. Ann's Church

The original Plan of Detroit called for the triangular lot at the center of each section to be reserved for public spaces or buildings, such as parks, schools, and churches. On October 2, 1806 the governor and judges directed that the new Roman Catholic Church was to be built in center of Section 1. No property was conveyed at the time, and construction did not begin on the church for more than a decade.

The Corporation of St. Ann's Church was formally granted the center lot of Section 1, in addition to lots 42-47 and 86-91 in that section, on October 17, 1816. The grant was made on the conditions that lots 40, 41, 84, and 85 remain vacant, as they were being used as an informal connection to Randolph Street; and that the church building be constructed by December 31, 1818, or else the central triangular lot would revert back to public ownership. On May 27, 1818, the governor and judges permitted the church to enclose and build upon the side street that ran on the north side of the center triangle, then called Virginia Street.

Image courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

This violation of the city plan opened the door to more infractions. The church lots that were used as an unofficial road were later officially incorporated into Randolph Street. Congress Street, which used to end at Bates Street, was continued straight through Section 1 in 1836 to conform with the Military Reserve gridiron.

In the late 1940s, two-thirds of Bates Street in Section 1 were eliminated as part of the Civic Center project. Because the sewer beneath Bates Street could not be removed, the City-County Building and an adjacent parking garage were designed to straddle the old right-of-way. The Civic Center project also erased all of the rectangular blocks platted by the governor and judges south of Jefferson Avenue.

Private Claims

The Woodward Plan's greatest impediments of all were the ribbon farms closest to the city. These were owned by Detroit's wealthiest men, one of whom was also the Governor of Michigan. Imagine that the core of the city was only just expanding today, and that the largest tracts of land were owned by Rick Snyder, Manuel Moroun, Mike Ilitch, and Dan Gilbert. How interested do you think they would be in continuing an idealistic city plan that reserved large amounts of land for public ownership? Detroit's major landowners were chiefly interested in dividing their tracts in the quickest, cheapest way possible, maximizing profits and minimizing the amount of land dedicated to public squares and grand avenues.

The sale of federally owned land in Michigan led to a boom in the territory's population in the 1830s. It was at this time that farms close to Detroit began to be subdivided. The first subdivisional plat of private land to be submitted to the Wayne County Register was that of portion of the Antoine Beaubien Farm in 1831. The plat anticipated the continuation of Larned Street, Jefferson Avenue, and Woodbridge Street. This plan called for a street to be run north through the farm, called St. Antoine Street.

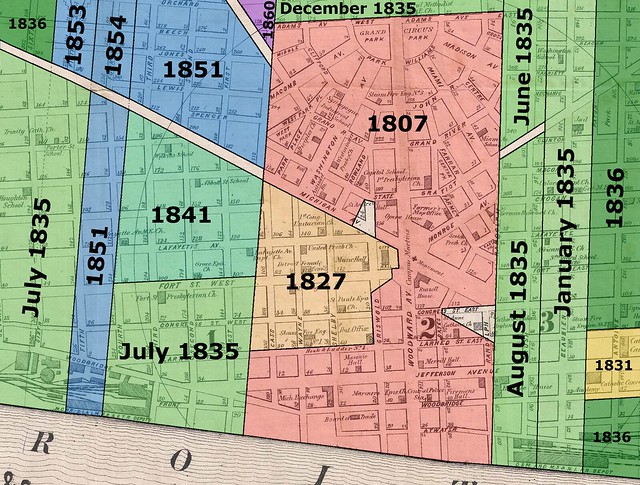

The years in which subdivisions in the heart of Detroit gained legal recognition.

CLICK HERE FOR A LARGER VERSION OF THIS IMAGE.

It's fair to say that 1835 was the year the Woodward Plan was cut off forever. It was then that a multitude of new subdivisions close to the center of the city were recorded by the county. First was the Lambert Beaubien farm, through which Beaubien Street now runs. Although drawn up in 1831, it was not received by the county register until January 1835. This plan made some attempt at cohesion, continuing streets from the Military Reserve (Lafayette, Fort and Congress) as if they were not "interrupted" by the Woodward Plan. This plat was followed by subdivisions of the Brush, Cass, Forsyth and Labrosse farms, as well as the southernmost parcels of the Park Lots, all before the year was out.

The image below is a satellite photo of downtown Detroit with Abijah Hull's 1807 plat of the Woodward Plan superimposed. Lots that remain more or less intact are outlined in white. Lots that have been removed or that have never been implemented at all are drawn in red. Please click here to explore the full-resolution version of this image. (The file is 6MB and takes a moment to load.)

CLICK HERE FOR A LARGER VERSION.

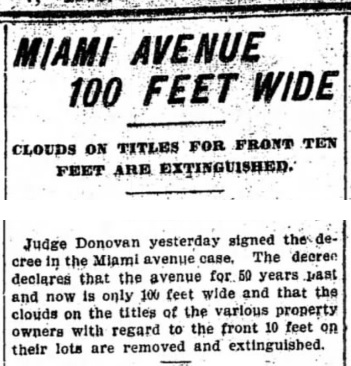

Miami Avenue

One last violation of the Woodward Plan is worth mentioning. Miami Avenue, according to the plan, should have had a full right-of-way of 120 feet. In the 1840s, when it was yet a residential area, parts of either side of the avenue were fenced in by various homeowners, narrowing the public right-of-way to 100 feet. The issue grew increasingly contentious as commercialization crept in. The builders of stores and hotels required a clearly defined building line.

Years of legal battles finally came to a decisive end when the proprietors on Miami Avenue filed a bill in chancery court in July 1900, arguing that the thoroughfare should be defined as 100 feet wide and that ten feet of the public property in front of each parcel be given to that lot's owner. The judge ultimately ruled in favor of the owners in May 1901.

Source: Detroit Free Press, May 7, 1901.

Five years later, business owners along the narrowed avenue wanted to give the thoroughfare a new name. What name did they choose? Why, Broadway of course!

Source: Detroit Free Press, June 30, 1906.

Consequences

By 1900, Detroit's population grew to one hundred times what it was in 1830. Without a proper street plan, the city had grown so disorganized that the Detroit Board of Commerce hired Frederick Law Olmstead Jr. and Charles Mulford Robinson in 1905 to suggest changes to the city street system. Robinson, an early leader in the discipline of urban planning and author of The Improvement of Towns and Cities, had this to say:

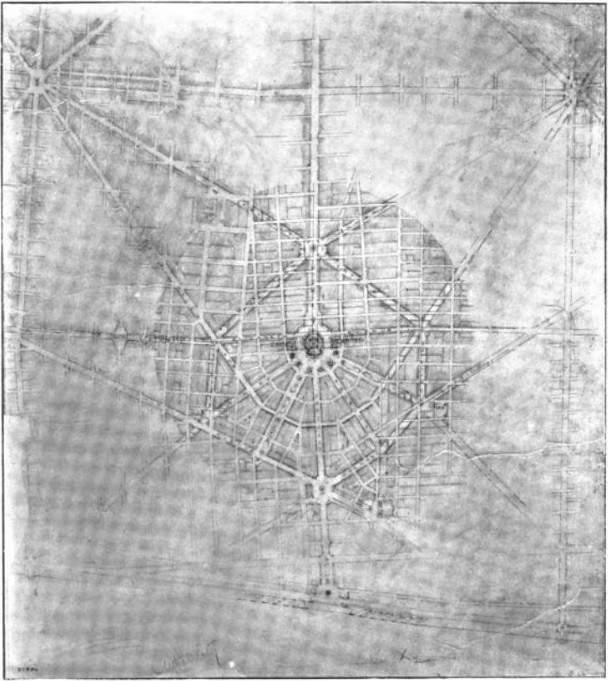

Nearly all the most serious mistakes of Detroit's past have arisen from a disregard of the spirit of the Governor and Judges' plan. If the plotters of the farms had had respect for that, instead of each going his own way, the streets beyond Cass and Brush would not have had the jogs they now have, and Detroit would have had a better chance for beauty and harmony, to say nothing of the added convenience and economy for its citizens in getting about.In 1915, the Detroit City Plan Commission brought in Chicago city planner Edward H. Bennett to advise on the future course for the city. The final report lamented,

It is most unfortunate that we have not developed the city entirely according to the Woodward plan. It is more than unfortunate that as the city extended itself, the same ideas and the same street lines could not be maintained; and that small parks have not been provided in the section north of Adams avenue. If this had been done, Detroit would have been a very much more handsome and convenient city.Bennett's suggestions for Detroit included the addition of parks, plazas, and diagonal avenues, as well as the completion of Grand Circus Park--elements that the Woodward Plan took for granted.

One of Bennett's suggestions for the Plan of Detroit. (Source.)

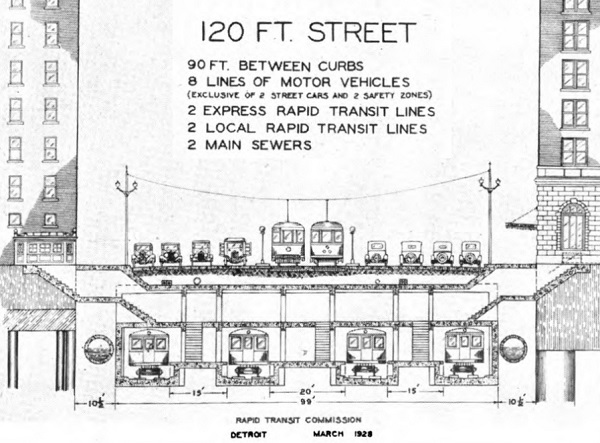

The absence of adequate crosstown thoroughfares and lack of public plazas weren't the only problems that resulted from the abandonment of the Woodward Plan. Avenues that should have been 120 or 200 feet wide were built to as little as 66 feet wide just outside the core of the city. In order to relieve severe traffic congestion, an array of street widening projects became necessary.

In 1925, Detroiters voted to expand Woodward Avenue to 120 feet wide, from Adams Avenue up to Highland Park. The city council approved the project in 1927, but the condemnation trial did not begin for another two years. A mistrial was declared after the death of a juror, and a final verdict did not come until 1932. Just the first portion of Woodward to be widened--between Kirby and Baltimore Streets--did not open until 1934, nine years and $2.5 million dollars ($44 million in today's money) after the process began. All of this just to bring Woodward Avenue up to the width it was originally prescribed more than 120 years before!

In a 1985 interview with researcher Perry Norton for a paper on the Woodward Plan, Walter Blucher, former CEO of the Detroit City Plan Commission, said that this widening project entailed "cutting chunks off the front of five or six churches, and for that I was consigned to hell at least once a week." In order to save Central United Methodist Church, the easternmost portion was demolished, a section was torn out of its center, and the remaining facade was rolled back twenty-six feet.

Image courtesy Wayne State University. (Source.)

Similar projects on Detroit's other main thoroughfares were no less of a waste. The widening of Michigan Avenue, for example, permanently mutilated Corktown's main thoroughfare. Had the Woodward Plan been followed from the beginning, there would have been no need to squander precious time and resources on condemnation proceedings, demolition, and rebuilding. So much more our historical architecture might have been saved.

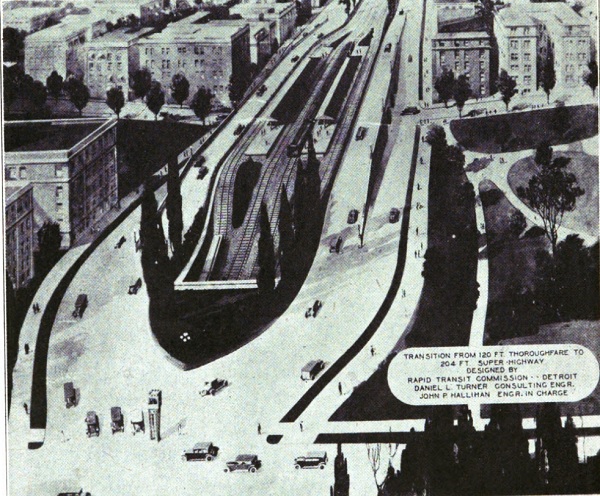

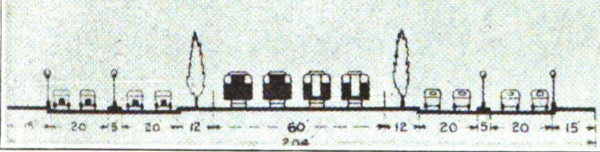

In 1924, city engineers devised a rapid transit plan for Detroit and standardized the rights-of-way that such a system would require. They called for highways 120 feet wide and superhighways 204 feet wide. One hundred twenty feet can accommodate pedestrian traffic, street trees, automobile traffic, street cars, a complete subway system, and other infrastructure. Superhighways would have contained all of these modes of transit, but with trains running at the surface level between opposing lanes of automobile traffic.

(Source.)

(Source.)

A breakdown of the 204-foot right-of-way. This system could easily

fit into Woodward's 200-foot grand avenues with minor alterations.

Many roads in Detroit were widened to 120 and 204 feet wide in anticipation of this modern rapid transit system. But by the time the lengthy condemnation proceedings ended, and hundreds of millions of dollars were spent on condemnation awards, demolition, and repaving, the Great Depression had arrived. When Detroit's economy finally recovered in the 1940s, there was insufficient political will to continue the project. Had Detroit's avenues and grand avenues been built according to Judge Woodward's specifications, all of the time and money spent on acquiring land could have instead been used to begin constructing the rapid transit system itself.

Woodward's Final Years

In 1824, the Territory of Michigan was to cease operating under the "governor and judges" system, and instead adopt a government with separate executive, legislative, and judicial branches. President James Monroe was to appoint the members of the new Supreme Court of Michigan. Jealous lawyers jockeying for positions on the court publicly attacked Woodward, making him a scapegoat for practically every problem that had occurred in the territory since 1805. Some even falsely accused Woodward of holding court in a drunken state. Monroe removed Woodward's name from the list of nominees in light of this accusation. By the time the president learned the truth, the appointments had already been confirmed by the Senate. Woodward's final term expired February 1, 1824, and he returned to Washington a month later.

After Gabriel Richard, Lewis Cass, and other prominent Detroiters came to Woodward's defense, Monroe offered Woodward a Federal district court position in the Territory of Florida. The vindicated judge arrived in Tallahassee in October 1824.

In Florida, Woodward was well-liked and he served capably, but his new career did not last long. After occupying the bench just two years, he died on June 12, 1827, at the age of fifty-two. The cause of death remains unknown. According to biographer Frank B. Woodford, author of Mr. Jefferson's Disciple: A Life of Justice Woodward, "He was buried June 13, from the residence of George Fisher, with the rites of the Masonic order. If his grave was marked, its location has long since been forgotten." Claude Kenneson of the Tallahassee Historical Society told me that this could mean that a ceremony was held in Fisher's home in Tallahassee and that Woodward was buried in whatever cemetery might have been available in the young city; or that Woodward was buried on a plantation owned by Fisher. Fisher did purchase 160 acres about ten miles northeast of Tallahassee the year before Woodward died, and it was commonplace for plantations to have their own small family cemeteries. Whatever the case may be, Woodward's final resting place will likely remain a mystery forever.

During his lifetime, Augustus Woodward's ideas regarding urban planning and Detroit's future were sometimes met with puzzlement and even outright ridicule. He predicted that the modest town of Detroit would grow into a great metropolis; he understood the importance of enlightened city planning in the nascent United States, and how narrow the window of opportunity to act was; and he somehow knew just the right proportions of broad avenues, narrow streets, and public spaces for creating a beautiful and successful city. If urban planners a century ago such as Charles Mulford Robinson and Edward H. Bennett recognized the legitimacy Woodward's ideas then, the judge should be all the more vindicated today, in the age when the failed experiment of mid-twentieth century style tract housing is coming to an end, and when downtown Detroit is experiencing a great resurgence.

When Woodward left Detroit in 1824, a number of friends and associates held a going away party for their beloved judge. It seems appropriate to close here with the words delivered that day by Detroiter John McDonnell:

Be assured, sir, that when the little bickerings and prejudices of the transient hour are buried in the vale of oblivion, when the pulse of the caluminator shall have ceased to beat, when his organ of detraction will no longer furnish a banquet to the worm; and when himself and his character are sunk in forgetfulness, a generation, yet unborn, will do justice to the man in whom were united the philosopher, the patriot, the judge and the philanthropist. In that day, the cultivation of the sciences will add an additional ray to the light which will shine around your name, and a grateful posterity will venerate the memory of him whose labors have enlarged the boundaries of their knowledge.

A lesson in unintended consequences of gov't action

ReplyDeleteAlso explains why Capitol Park is such an urban design success, imagine if that was every block...

ReplyDeleteSection 8, where Capitol Park is located, is the most built-up section and probably the best example of the Woodward Plan's potential. It's only flaw is that Griswold should have bent to meet Michigan Ave. at a 90 degree angle.

DeleteThe most intact section as far as streets go is Section 7, where the Skillman Branch Library is located. But because the Hudson block is still empty and because there is a library instead of a central public meeting space, it's not quite as beautiful or functional as Capitol Park.

Paul, I have a few questions for you.

DeleteFirst, what is the first map of the Military Reserve supposed to show? Is the blue supposed to represent the city's requst of the lands of the military reserve? What is the "Macomb Line"?

Secondly, on Beaubien you mention the Antoine Beaubien Farm being the first private plat in 1831 in one paragraph, but by the next you write this:

"First was the Lambert Beaubien farm, through which Beaubien Street now runs. Although drawn up in 1831, it was not received by the county register until January 1835."

Is this supposed to imply the farm changed hands within the family over those four years or something? Or are these two different farms you've talking about?

On the old Military Reserve map, the pink lines show the original boundaries of the entire reserve, and the blue lines were an early suggestion of boundaries where the federal government would still keep part of the land, but I'm not sure if any partial grants actually followed the blue lines.

DeleteThe Macomb line is just the eastern border of the Macomb farm, which later became the Cass farm.

I can see how what I wrote about the Beaubien farms was confusing. I'll try to reword it here... The Lambert Beaubien and Antoine Beaubien farms were different tracts of land. The first plat recorded by Wayne County of any private land (as opposed to the Woodward Plan, which was laid out on the publicly owned Commons) was a small part of *Antoine* Beaubien's farm. Surveyor John Mullett dated his "Plat of part of Antoine Beaubien Farm as divided into Town Lots" August 3, 1831, and was recorded by Wayne County on August 9. That little subdivision is highlighted in gold near the lower right corner of this image: https://c2.staticflickr.com/8/7531/27289130075_193babcef2_o.png

In the later paragraph, where I'm talking about how and why the Woodward Plan was abandoned, I consider 1835 to be the year that it officially died. There was a land boom at the time and everybody suddenly wanted to cash in. The first of the many subdivisions to be made around Detroit in the particular year of 1835 was part of the farm of *Lambert* Beaubien, which is in the image I linked to above, where it says "January 1835." Sorry about the confusion, I hope this explains it!

Can you tell me where the base map for your map showing when subdivision were legally recognized came from? It shows the location of Farmer's Map Office. John farmer is my 3rd great grandfather and I am trying to research the family history in Detroit.

ReplyDelete