Seven Mile Road in northwest Detroit in 1930. (Virtual Motor City)

While studying the borders of Detroit, I've come to learn a lot about how it's grown from a small, congested city into the sprawling metropolis that it's become. I've also recently had a conversation about Detroit's preponderance of single-family houses with journalist Aaron Mondry, for a podcast project that was ultimately shelved. Our discussion inspired me to share these important facts about our region's development and to clear up common misconceptions about it. For example, I had always assumed that suburban sprawl started in the 1950s, during the post-WWII building boom. But I was surprised to learn that...

#1: A 1920s real estate bubble shaped metropolitan Detroit.

(freep.newspapers.com)

(freep.newspapers.com)As the United States recovered from the First World War, it was entering into a period of economic prosperity known as the Roaring Twenties. Unemployment was low and banks were happy to loan money for home construction, resulting in a flurry of building activity all across the country. Detroit was in an especially sweet spot, as the wealth pouring in from the automobile industry fueled an abnormal amount of building activity, being surpassed only by New York and Chicago in terms of construction volume. At the peak of the building boom in 1925, the city issued a record-smashing 41,891 building permits, including 11,951 permits for new single-family homes. When the National Association of Real Estate Boards held its annual convention in Detroit that year, its president, Charles G. Edwards, called Detroit "the miracle city of the country." ("Detroit Wins Warm Place in Hearts of Nation's Realtors." Detroit Free Press, Jun. 28, 1925.)

This was more than a growth spurt—it was the beginning of a movement that would fundamentally change the way Detroiters inhabited the landscape. Richard L. Maxon, a suburban property salesman for the Detroit realty firm Wormer & Moore, described it this way to the Detroit Free Press in 1928:

Twenty years ago there was a sharp dividing line between living in the city and living in the country. Then the country estate was in reality a farm; it was devoid of such conveniences as gas, electricity and running water, which the city homes enjoyed; social life was almost unknown; and the city, although perhaps only a few miles away, could be reached only by a long and tiresome journey. As a result, the better class of homes were built in the city, and except for the dwellings on the largest and most prosperous farms, country homes were humble and unpretentious. Now, however, the situation is gradually reversing itself; for today the better class of new homes are being built in the suburban areas, away from the noise and confusion of the city. They have every city convenience available with perfect roads for the motor car. Schools in the suburban areas are in many cases even superior to those of the metropolian districts; social life, centering around the country club, is even more complete than in town.

("Suburb Trend Gains Steadily." Detroit Free Press, Jul. 8, 1928.)

It had always been common to build single homes on the edge of town, where land is cheaper and one was closer to that division between the city and country. But this practice took on epic proportions in Detroit, which had plenty of countryside in which to expand and a well-employed population eager to borrow money to build homes of their own. Between 1916 and 1926, the city annexed 90 square miles from the surrounding rural townships. People were leaving Old Detroit behind, and crossing Grand Boulevard to dwell in one of the many fashionable suburban neighborhoods still within the city limits of New Detroit.

Today's city borders superimposed over an 1876 map of Wayne County.

Today's city borders superimposed over an 1876 map of Wayne County.(University of Michigan)

The suburban communities beyond the city limits also emerged during this time. Fifteen new villages were incorporated in the metropolitan area in the 1920s: Bloomfield Hills, Clawson, Berkley, Huntington Woods, Pleasant Ridge, Oak Park, Halfway (later East Detroit, now Eastpointe), Center Line, Roseville, Garden City, Inkster, Melvindale, Allen Park, Lincoln Park, and Lochmoor (now Grosse Pointe Woods). Additionally, the older villages of Ferndale, Royal Oak, Farmington, River Rouge, Hamtramck, and Dearborn incorporated as cities all in this decade.

The expansion of Detroit and nearby municipalities, 1910-1938. (Hathi Trust)

The expansion of Detroit and nearby municipalities, 1910-1938. (Hathi Trust)Following the 1925 construction peak, 1926 saw a 4% dip in building permits issued in the city, and a 12.5% drop in the number of new single-family homes. However, the estimated valuation of all projects rose by $3.5 million, since banks were loaning for larger projects. Regardless, the city's realtors continued to promote Detroit real estate as a safe investment, which was guaranteed to increase in value indefinitely. Advertisements for building lots often seemed to be less about building homes, and more about the profit one would ultimately reap when reselling the property.

Detroit Free Press, Jul. 27, 1924. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, Dec. 5, 1926. (freep.newspapers.com)

By 1927, Henry Ford was beginning to observe something about his cars that few automakers or home builders in Detroit would have admitted about their products: that the market was becoming saturated. In May of that year, soon after the fifteen-millionth Model T rolled off the assembly line, Ford shut down operations for six months in order to retool his factories to begin production on his new "Model A." The sudden laying off of 60,000 workers sent a shockwave through the city's economy, and home construction figures continued to fall.

In the mad rush for easy profits, developers chopped up huge swaths of land in and around Detroit into subdivisions, determining the layout of our built landscape as we know it. An investigation by the State of Michigan found that "hundreds of new subdivisions were created primarily to take advantage of the speculative fever," and that most subdivision activity "was purely speculative in nature, and had little or no relation to any normal present or future suburban growth." The report, published in 1939, found that 54% of all subdivision activity in the metropolitan area outside of Detroit in the last century had taken place in just three years: 1924, 1925, and 1926. While the metropolitan region's population had increased 479% since 1900, there was a 1105% rise in subdivision activity outside of the city in the same period. By the time the building boom ended—followed by the 1929 stock market crash—Detroit was surrounded by many partially-built subdivisions, which became the template for continued suburban sprawl as subsequent waves of building activity filled up the vacant lots.

Lathrup Village, founded in Southfield Township in the early 1920s, shows few homes built by the time this aerial photograph was taken in 1940.

Lathrup Village, founded in Southfield Township in the early 1920s, shows few homes built by the time this aerial photograph was taken in 1940.(Oakland County Property Gateway)

The San Bernardo Park Subdivision No. 3, at Northwestern Highway and Pembroke in Detroit, was platted in 1925, but remained largely unbuilt when this aerial photograph was taken in 1949.

The San Bernardo Park Subdivision No. 3, at Northwestern Highway and Pembroke in Detroit, was platted in 1925, but remained largely unbuilt when this aerial photograph was taken in 1949.(digital.library.wayne.edu)

How did people think it was practical to build houses up to 20 miles away from downtown Detroit nearly a century ago? Before the US Interstate Highway System, was such a thing even feasible? Well, as it turns out...

#2: Sprawl-feeding superhighways existed back then.

(freep.newspapers.com)

(freep.newspapers.com)Long before the US Interstate System, the radial avenues that extend from Detroit's center—Woodward, Gratiot, Grand River, Michigan, and Fort—made it possible to live far outside of the city center but still drive downtown for work each day. The widening of Woodward Avenue north of Six Mile Road from a two-lane dirt road into a 200-foot-wide highway beginning in 1923 made real estate all along the corridor suddenly much more valuable. Many of metropolitan Detroit's most exclusive residential communities were founded here in this period.

A 1924 advertisement by the Greater Woodward Avenue Association. (freep.newspapers.com)

A 1924 advertisement by the Greater Woodward Avenue Association. (freep.newspapers.com)"Wider Woodward Avenue" was unlike any other road in the world at the time, and Detroiters were eager to see more infrastructure like it. When the Detroit Rapid Transit Commission compiled a report on traffic conditions in 1924—citing a 343% increase in automobile registrations in just the previous six years—it recommended a system of 204-foot-wide "superhighways," just like the new Wider Woodward Avenue, to be constructed about three miles apart throughout the surrounding suburbs.

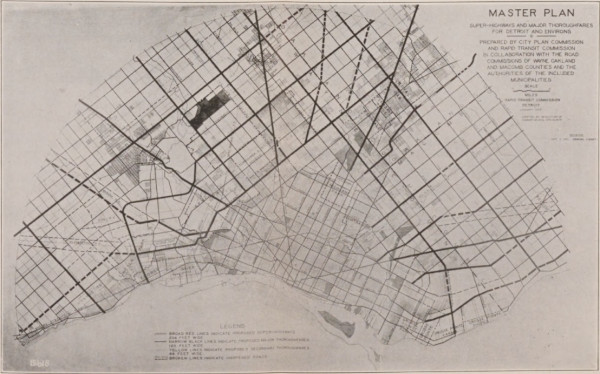

A map of the proposed superhighway system from the 1925

A map of the proposed superhighway system from the 1925version of the Rapid Transit Commission's report. (Hathi Trust)

Below is a satellite image of the Detroit area with the 1925 version of the superhighway plan superimposed. Although the scheme was often revised, many of these originally designated superhighways remain major thoroughfares today. In addition to their generous width, they are characterized by the grassy medians which separate opposing traffic lanes, requiring the use of a "Michigan left".

By 1930, 103 miles of superhighways were paved with double lanes of concrete, in addition to hundreds of miles of subordinate roads paved throughout suburban Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties. The landscape was being transformed to facilitate automobile travel, which in turn allowed subdivisions to develop in formerly inaccessible areas.

Detail from a 1926 advertisement for the Westwood Hills subdivision in Dearborn. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detail from a 1926 advertisement for the Westwood Hills subdivision in Dearborn. (freep.newspapers.com)Although the automobile had undoubtedly shaped suburban Detroit, in the view of property owners and developers in the 1920s...

#3: Public transportation was considered essential.

A 1924 advertisement for the Hazelcrest subdivision in Royal Oak Township,

later part of the City of Hazel Park. (freep.newspapers.com)

Not everyone who moved to new suburban communities wanted to rely exclusively on automobiles for transportation. The suburbs promised country homes with city conveniences, and the public still expected public transportation to be among those conveniences. Real estate advertisements often touted the advantages of living in developments near public transportation—and when there were none, developers frequently established property improvement associations which lobbied for such facilities.

Detroit Free Press, Nov. 16, 1924. (freep.newspapers.com)

All of the suburban "superhighways" were eventually supposed to include rapid transit railways. When public transit was extended to new suburban areas, realtors proudly advertised the new development.

A 1925 advertisement for the Brightmoor development. (freep.newspapers.com)

A 1925 advertisement for the Brightmoor development. (freep.newspapers.com)If you are wondering why the city expanded into areas before it had a plan to service it with public transportation facilities, you might be surprised to learn that...

#4: City government had nothing to do with annexations.

(archive.org)

(archive.org)Up until 1909, the State of Michigan held absolute control over the incorporation cities and the location of their boundaries. The Home Rule City Act was an attempt to put the power over city boundaries into the hands of local citizens, rather than politicians. The law set up a process for annexing new land to cities which started with a petition and was decided by a local election. As long as the petitioners filed their paperwork correctly and had the votes to back them up, no government official could stop an annexation.

Detroit's realtors quickly learned that they could increase their profits by taking advantage of this process. Land was much more valuable once it was annexed to the city, since properties would then be entitled to city services such as sewers, paved streets, and fire protection. In 1917, prominent realtors Daniel J. Campau and William Hillger openly campaigned for a large east-side annexation, with Hillger organizing the petitioning process. Realtors also paid for advertisements in support of annexation election proposals.

An advertisement in support of a major annexation in 1916, listing the names of organizations in support of it, almost all of which are real estate companies.

An advertisement in support of a major annexation in 1916, listing the names of organizations in support of it, almost all of which are real estate companies.Detroit Times, October 28, 1916. (loc.gov)

Between 1905-1917, annexations tripled Detroit's landmass. In 1916 alone, 21 square miles were added onto the city. Assured of unlimited future growth, the city government issued hundreds of millions of dollars in municipal bonds for school buildings, playgrounds, sewers, water mains, street lighting, grade separations at railroad crossings, parks, hospitals, a new bridge to Belle Isle and a new art museum. Despite the miraculous "growth" that Detroiters could see all around them, City Comptroller William J. Nagel shocked civic leaders in 1923 when he announced that the city was broke. Detroit had reached the legal limit of municipal bonds that it could sell, and public improvements worth tens of millions of dollars had to be delayed indefinitely. To keep the problem from getting worse, Nagel recommended "close scrutiny of further annexations of undeveloped territory." ("Nagel Insists City Is Beyond Its Bond Limit." DFP, Sep. 5, 1923.)

Detroit Free Press, Aug. 19, 1923. (freep.newspapers.com)

In a strange way, the city's building boom paradoxically enabled it to borrow even more. Because thousands of brand new buildings were going up, the total assessed valuation of property in the city grew by leaps and bounds. Since Detroit's borrowing limit was a percentage of its total assessed property valuation, an increase in this figure allowed the city to sell more bonds, allowing some relief in the backlog of munipal improvements.

When annexations from Redford, Greenfield, and Gratiot townships were proposed in 1923, the city's Corporation Counsel, Richard I. Lawson, met with the Wayne County Board of Supervisors to plead with them not to place the proposals on the ballot. However, their hands were tied—as long as the annexation petitions were in order, the board was forced to proceed with the election process. ("County Board Deaf To City's Economy Plea." DFP, Aug. 29, 1923.) According to Joseph A. Martin, Commissioner of Public Works, existing city infrastructure at the time could have accommodated a population of two million. "Detroit does not need more area any more than the average home needs to annex a dozen extra bedrooms," he told the Free Press. ("Vote No, Lodge, Martin Urge On Annexation." Aug. 30, 1923.) One Free Press editorial commented:

This city now has all the territory it needs, and considerably more than it can comfortably or even decently take care of in the present state of its finances. There is just one argument for further annexation of the ordinary sort, the pride of numbers, and that under prevalent conditions, should not be given consideration. ... [T]he three proposals for annexation of territory to Detroit which are about to be placed before the voters ought to be emphatically rejected. All of them appear to be real estate enterprises being pushed primarily by subdividers for the benefit of property which they have sold, or which they hope to sell. ... Detroit must no more be an easy mark for suburban communities that want to get the comforts and conveniences of a big city without paying for them.

("No More Annexation." Detroit Free Press, Sep. 6, 1923. Editorial.)

Despite these protests, the Detroit Real Estate board was firmly in favor of annexation. "If Detroit is to continue to be a city of single and semi-detached homes, we must continue to extend our boundary lines," the board said in a statement. ("Realtors Ask Annexation." DFP, Sep. 4, 1923.) The public voted in favor of all three annexations.

Detroit Free Press, Oct. 8, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, Oct. 8, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)Officials tried to halt the city's expansion again in 1925, when annexations totaling 17 square miles were proposed. When Mayor John W. Smith asked all city departments to calculate the cost of taking on the territory, the total was found to exceed $24 million. ("Officials Hit Annexation." DFP, Mar. 20, 1925.) The Department of Public Works reported that it was already 10 years behind in paving streets, and that the city didn't need any more. Only 978 of the 1,945 miles of streets inside the city were paved as it was. ("Paving Work 10 Yrs. Behind." DFP, Apr. 3, 1925.) In one of his weekly radio broadcasts over station WCX, Mayor Smith warned listeners of the "added costs to the taxpayers of Detroit in the extension of sewer facilities, of schools, of fire and police protection, and of lighting facilities" if the annexations were approved. ("Voters Urged To Be Cautious." DFP, Sep. 3, 1925.) The real estate interests shot back with advertisements telling voters that annexations "will cost you nothing." Again, the proposals won.

Detroit Free Press, Sep. 27, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)

The annexation approved by voters on October 6, 1925 added 34 square miles to the city. That was greater than the total area covered by Detroit in 1905—a size which had taken a century of growth to reach. The new Commissioner of Public Works, John W. Reid, pointed out that this added 726 miles of dirt roads to the city—a situation which he said "cannot be even approximately coped with under conditions as they now exist in the extensive areas affected." He also reported:

Buildings have been erected along miles of these streets and roads. These building operations, together with continued rainy weather, have contributed very largely to cut up the roadways. Installations of water, sewer and gas facilities, necessary to serve the properties, have distrubed and will continue to disturb, the normal ground conditions. The very general reliance on the use of the automobile to get to and from these areas by the people living in them makes the situation tremendously acute.

("Much Street Work Needed." Detroit Free Press, Nov. 29, 1925.)

Commissioner Reid told the city council that the annexation would require extensions to the city sewer system totaling $101 million—$1.5 billion in today's dollars. This was in addition to the $39.6 million the city already needed for a sewer interceptor and disposal plant. ("100 Million Sewer Asked." DFP, Dec. 25, 1925.) Soon every city department was feeling the cost of "growth" as Mayor Smith slashed $31.6 million from his proposed 1926-27 budget "to allow as much money as possible for the sewer program." ("31 Million Cut From Budget." DFP, Feb. 28, 1926.)

The voters of Detroit finally finally broke their long record of favoring annexations when they rejected all four of such proposals appearing on the November 2, 1926 ballot. The defeated annexation areas were: the part of Royal Oak Township that is today the City of Hazel Park; the part of Warren Township south of Stephens Road and between Shoenherr and Ryan roads; and the entire cities of Lincoln Park and Melvindale.

"How Detroit Has Expanded," from Detroit Has Decided Not to Grow Too Rapidly (The American City Magazine, January 1927). (hathitrust.org)

"How Detroit Has Expanded," from Detroit Has Decided Not to Grow Too Rapidly (The American City Magazine, January 1927). (hathitrust.org)Hat tip to Nailhed!

The comparatively small size of Detroit before 1910 and its extremely rapid growth according to a new kind of development pattern led to a strange situation for what was once the nation's fourth-largest city...

#5: Most of the city is actually "suburban."

The vicinity of Wyoming and Puritan avenues, 1931. (Virtual Motor City)

The vicinity of Wyoming and Puritan avenues, 1931. (Virtual Motor City)There are generally two land development patterns by which cities grow: "traditional" and "suburban"—and the 1920s real estate boom brought with it a massive shift from one method to the other.

Most of the city outside of Grand Boulevard has developed according to the suburban method.

Most of the city outside of Grand Boulevard has developed according to the suburban method.The suburban development pattern is the dominant city growth pattern in North America today. In this system, various land uses (such as single-family, multi-family, business, etc.) are carefully segregated according to a predetermined plan. After buildings are constructed, their function and character are expected to remain unchanged until the end of time. Once a neighborhood is built up, it is "finished." Zoning laws and restrictive deed covenants are designed to prevent changes from occurring (such as tearing down a one-family home to build a duplex, or building a neighborhood corner store). The suburban development pattern has nothing to do with density, architecture, or detached houses—it's about: 1) our attempt to plan and control growth, and 2) to freeze it in time.

A detail from a 1924 advertisement for Detroit's Curtis Avenue Subdivision, located northeast of Wyoming and Curtis avenues, stressing the benefits of property restrictions.

A detail from a 1924 advertisement for Detroit's Curtis Avenue Subdivision, located northeast of Wyoming and Curtis avenues, stressing the benefits of property restrictions.(freep.newspapers.com)

Cities grew differently under the traditional development pattern. A farmer at the edge of town a century ago might have decided to sell out and subdivide his land into streets and building lots. The lots were typically sold at public auction. The new owners generally built what they wanted to, but typically low-cost investments like cheap wooden houses would often spring up on new streets. When enough people were living in an area, owners could petition city hall to pave the street, install a sewer, etc. If that part of the city was growing, it might make sense for a lot owner to knock down their cheap house and build an expensive brick home, or some other more substantial building. This was considered to be a sign of progress, since the land was becoming more productive for the owner and yielding higher taxes for the community. Traditional development occurs slowly, over a long period of time, in small increments. Instead of following a predetermined plan, it responds to changes in its environment. Long before there was zoning, cities developed residential and commercial districts emergently. Remember that what we consider to be "downtown" Detroit was once the entire city, and contained districts of single-family houses.

The southwest corner of Madison Ave. and John R St., circa 1860s.

The southwest corner of Madison Ave. and John R St., circa 1860s.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

But why wait generations for a city to grow "incrementally" when you can just build the finished product all at once and have it now? And why risk spending your life's savings on a substantial home if there is no telling what kind of structures the other lot owners in your subdivision will build? The suburban development pattern was intended to solve these issues. Before modern zoning, developers typically attached restrictive deed covenants to their properties, determining what types of structures could be built (e.g., single-family homes only), and even requiring specific construction materials (e.g., brick only). Instead of selling bare dirt lots, suburban developers would add improvements to their subdivisions—such as street paving—and then include the improvement in the lot price. Lots were no longer sold at auction, but salesmen were hired to market properties to private buyers. The suburban development pattern promised efficiency, control and predictability, in contrast to the slow, messy, and chaotic process of traditional development.

Detail from a 1927 advertisement for Bloomfield Hills subdivisions sold by the Judson Bradway Co. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detail from a 1927 advertisement for Bloomfield Hills subdivisions sold by the Judson Bradway Co. (freep.newspapers.com)Despite these advantages, suburban development comes with many costs. Because housing is separated by type, families tend to be separated by class and income. Building and zoning restrictions yield less variety and utility in housing types. Separating residential and commercial activities makes communities less walkable and more car-dependent. A subdivision built all at once is going to age and lose its luster all at once. Overall, the limitations placed on suburban developments create places that are more susceptible to economic downturns and less productive in generating tax revenue.

Traditional development adapts to change and treats land like a precious resource. Suburban development is designed to resist change and views land as something disposable. That is why...

#6: Suburban sprawl initiated urban decay.

In 1907, the Board of Commerce adopted the slogan, "In Detroit—Life is Worth Living." It's not hard to find examples of Detroiters at the time waxing poetic about the City of the Straits. But after profitable new subdivisions began cropping up outside of the Boulevard, the city well regarded for its beauty and high quality of life was depicted by real estate developers as unfit for human habitation.

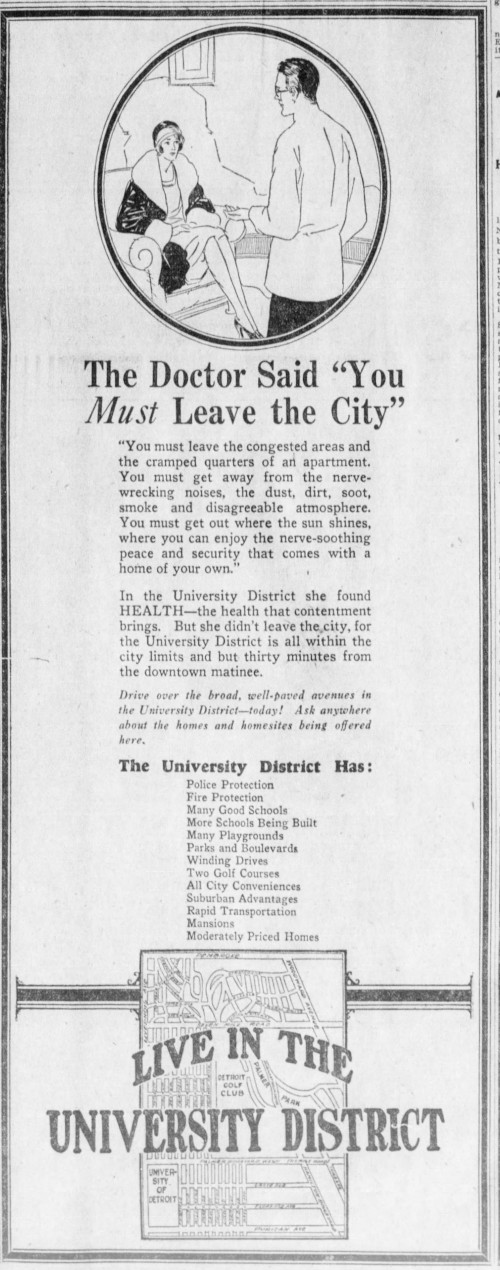

A 1927 advertisement for Detroit's University District subdivisions.

(freep.newspapers.com)

It is true that Detroit's population tripled between 1910 and 1930 due to the demand for industrial labor. Rent inside of the Boulevard was high, and families often had to share homes or take in boarders. The inner city was crowded at the time, but was it blighted? The prominent suburban realtor, John H. Castle, went so far as to claim in 1927 that the city was "entirely free of slums."

Detroit Free Press, January 2, 1927. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, January 2, 1927. (freep.newspapers.com)Despite Castle's claim, poverty obviously existed, and some inner city neighborhoods were in fact labeled "slums." On September 19, 1926, the Detroit Free Press printed a fascinating article, "Detroit Slum's Nice Places, Residents There Say," telling the story of fifteen families of Hastings, Beaubien, St. Antoine, Larned, and Congress streets who had moved out to the suburbs but returned to their old neighborhood because they preferred it. Although these residents all enjoyed the fresh air and open spaces outside of the Boulevard, "they complained of the suburbs as lonely, unsociable spots, with no community spirit, no amusements and little in the way of conveniences to which one is entitled." The increased commute times, longer distances to church and school, and the higher cost of living were also cited.

The photos on the right are captioned: "Top—Children of five races, all above weight and all athletic, slum residents. Below—Six who seem to be happy and above the average."

The photos on the right are captioned: "Top—Children of five races, all above weight and all athletic, slum residents. Below—Six who seem to be happy and above the average."(freep.newspapers.com)

A housewife who lived on Beaubien Street who was interviewed for the story told the Free Press:

What is needed in this district is not an exodus to the country, or to anywhere else, but better buildings. Most of the people who live down here like it, and would be willing to pay for modern flats if they could be had.

But the banks were not interested in loaning money to repair buildings in the older part of town, and landlords had little incentive to spend money since demand for space was so high. With the exceptions of the downtown business and shopping districts, Old Detroit was excluded from the building boom. Of the 40,204 building permits issued by the city in 1926, only 7,652 were for additions or alterations to existing structures. These repairs totaled just $13 million, compared to $170 million spent on new structures that year.

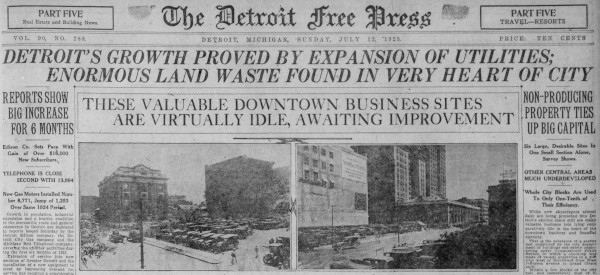

Detroit Free Press, Jul. 12, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, Jul. 12, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)A survey of downtown properties performed in the peak year of 1925 found 45 vacant lots just in the area bounded by Woodward, Adams, Second, and Jefferson avenues. Frank Burton, Commissioner of the Department of Buildings and Safety Engineering, found that six lots totaling $2 million in value were being used as parking lots. ("Non-Producing Property Ties Up Big Capital." DFP, Jul. 12, 1925.) Other valuable parcels were dotted with small and outdated buildings, utilizing only a fraction of the land's potential. Burton told the Free Press:

Throughout the downtown area there are many vacant lots lying idle while at the same time properties are not utilitized adequately. This becomes more noticable as the distance from the city hall increases until the better residential areas near Grand Boulevard are reached. Detroit may be compared to a mushroom which is rotting at the core and flourishing on the outskirts. There are large areas between the downtown financial section and the standard residential districts which are comparatively useless for want of proper development.

Signs of disinvestment within the Boulevard multiplied as the years went by. A Michigan population study published in 1932 claimed:

[T]he outward expansion of the city has pushed suburban develoment farther and farther away from the down-town section. As a result, smaller business districts have developed along the arterial highways and important cross streets, indicating that Detroit is deteriorating within the heart of the city itself and giving rise to the recent expression, "Detroit is becoming rotten at the core."

The June 1932 issue of Fortune magazine noted this recent trend of urban decay in American cities, and placed the blame on rapid and excessive suburban expansion. "Since the future greatness of the city was manifest as the will of God and since the omniscient fathers had laid out their plan for an all but innumerable population ... there was nothing for it but to spread and spread and pay and pay." The neglected "slum" areas, the magazine said, threatened to destroy cities financially "by a kind of creeping anemia."

Detroit realtor Judson Bradway described his experience appraising houses which were to be demolished for a slum clearance project. In "one of the very worst" homes he visited, a woman living there who had just moved from Tennessee claimed it was "heaven" compared to her previous home. As Bradway explained at the 1937 National Planning Conference:

It should be borne in mind that a large percentage of these buildings were single houses and had been allowed to run down during the depression period because the occupants were not paying any rent. Most of them, however, could have been repaired into quite confortable places when the occupants were again able to pay rent. [T]he Brewster slum clearance project ... did clear up a part of the worst section of our city, which however, was almost a paradise as compared with some of the slum districts I have seen in other cities and some of the living conditions I have seen in rural communities.

President Herbert Hoover promoted the idea of "slum clearance" as part of his economic recovery plan, and the Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 reserved millions of dollars in loans for this purpose. Eager to bring construction jobs into the city, Detroit took advantage of federal assistance to demolish a ten-block east-side area bounded by Mack, Beaubien, Wilkins, and Hastings, and to construct public housing on the site beginning in 1935. Although the benefits of projects like this are debatable, what is certain is that the federal government made the situation worse when the Home Owners' Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Administration—created in the early 1930s to finance and insure home mortgages—specifically excluded inner cities from assistance in favor of suburban areas.

Dr. Homer Hoyt, of Chicago, nationally known expert on the growth and structure of cities attached to the Division of Statistics and Economics of the Federal Housing Administration, sees little future value or use for decayed residential sections. The Housing Administration regards them with equal pessimism and examines such properties with extreme caution before issuing insurance on home mortgages in such sections.

("Slum Section Values Fading." DFP, Aug. 4, 1935.)

The Home Owners' Loan Corporation created "residential security maps," outlining areas to be included or excluded from government-backed mortgages. Areas which had been disinvested during the building boom were now designated "hazardous" for investment. Below is part of a 1939 residential security map for the Detroit area.

(detroitography.com)

(detroitography.com)Money kept on being steered away from maintaining and replacing older inner city buildings, and toward new construction farther from the center of town. The map below shows the location of new home construction in 1938.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)Unsurprisingly, people moved out of disinvested parts of Detroit. And it started long before the city's actual population peak in 1955. The Detroit Bureau of Government Research found that, between 1930 and 1940:

In the older sections of Detroit and the down-river communities, some areas have lost as much as 11.4% of their population... The loss or stagnation is no longer confined 'within the boulevard,' but extends roughly to the area bounded by Livernois, McNichols, and Conners Avenues plus the south-west area. Surrounding these declining areas are sections which gained population by as much as 50% during the decade. For the most part these areas were annexed to Detroit during the 1920's. Beyond these areas, the suburban areas ... had population gains in excess of 50% — ranging up to 500%.

(Citizens Research Council of Michigan)

The 1920s building boom had ushered in to Detroit a new kind of "growth"—one in which a fresh supply of farms and forests on the periphery of the metropolis must be constantly hacked up into subdivisions, while older parts of the city are continually discarded. An editorial in the July 1931 issue of House & Garden magazine told readers, "The industry of building never can be brought back to health until people learn to junk obsolete houses," in the same manner that old radios and automobiles are "junked."

Couldn't a developer have purchased neglected inner-city housing and simply build anew? Paradoxically, even though these buildings were occupied by poorer residents, the land itself was very expensive. One reason for the high property value is that, having grown according to the traditional development pattern, the land remained very productive for its owners—although that productivity was being misused by slumlords to extract wealth from disadvantaged families who had little choice in where to live. The land was so expensive that it was inconceivable that it could be purchased by any entity other than the US government, if part of a slum clearance program.

William Bunge, Direction of Money Transfers in Metropolitan Detroit. (1971)

(Cornell University Library)

Detroit's most disinvested inner-city neighborhoods were predominately occupied by Black people, immigrants, and poor people. Couldn't they have simply found places to live on the other side of the Boulevard, or even farther out in the suburbs? Well, not always, because...

#7: Suburbia was largely intended to exclude Black people, immigrants, and poor people.

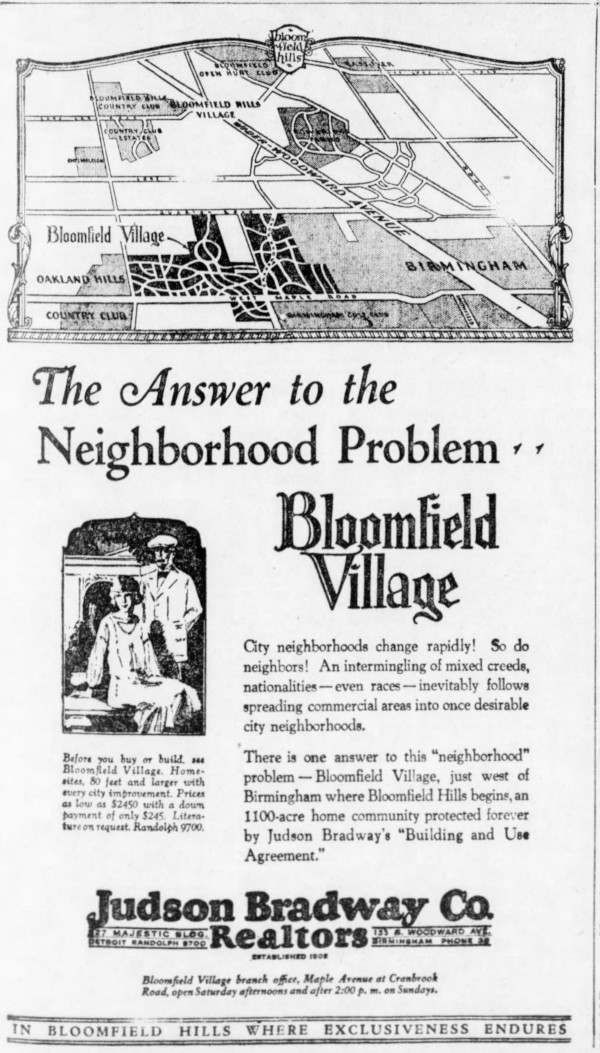

The Bloomfield Village subdivision in Bloomfield Township promised to be the "one answer" to the "problem" of "intermingling of mixed creeds, nationalities — even races."

Detroit Free Press, Jan. 13, 1929. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit's industrial growth in the early 20th century was dependent upon a large supply of human labor. Polish immigrants came by the thousands, with their population in Detroit growing from 50,000 in 1900 to 110,000 by the First World War. After the US government restricted immigration, the pressing demand for industrial labor was met by Black refugees fleeing the American south in the Great Migration. Detroit's Black population grew from 5,700 in 1910 to 120,000 by 1930. Although European immigrants could integrate fairly easily in the city, Black Detroiters were generally confined to older and disinvested neighborhoods.

After 60 years without any major instances of racial violence, multiple mob attacks on Black families moving into white neighborhoods broke out during the spring and summer of 1925, the peak of Detroit's building boom. White crowds harrassed Aldine and Fleta Mathis after they moved into a lower flat at 5913 Northfield Street on the city's west side. Fleta Mathis discharged a firearm from inside her home after a brick was thrown through her window on April 15, and she was arrested and charged with "careless use of firearms." On June 23, Dr. Alexander Turner was driven away from his new home at 4755 Spokane Avenue by a mob of 5,000 white people, who vandalized the house, threw out the furniture, and smashed the windows of his automobile as he fled. When Vollington and Agnes Bristol attempted to move into a rental property they owned at 7810 American Street on July 7, several hundred armed white demonstrators gathered in front of the home, firing shots into the air. Police were forced to guard the house for several successive nights. John W. Fletcher moved into 9428 Stoepel Street with his wife and two sons on July 10. As a mob of 4,000 white people hurled objects at the house, breaking every single window in it, Fletcher fired a rifle from a second story window, hitting the thigh of a white youth, who recovered. The Fletchers moved out one day later. The home of Dr. Ossian and Gladys Sweet, 2905 Garland Avenue, was similarly attacked on September 9, one day after the family moved in. As a mob of 800 pelted the home with rocks and bottles, Dr. Sweet opened fire from the second floor, hitting and killing a man on the porch of a nearby house. Dr. Sweet and other members of the household were charged with murder, but acquitted.

Mayor John W. Smith blamed the Ku Klux Klan for inciting the mob attacks, but he also urged that Black people should stay in their own neighborhoods:

"I deprecate most strongly the moving of Negroes or other persons into districts in which they know their presence may cause riot or bloodshed.... It does not always do for any man to demand, to its fullest, the right which the law gives him. Sometimes by doing so he works irremdiable harm to himself and his fellows."

—John W. Smith, Mayor of Detroit

("Smith Blames Klan Politics For Race Rows." DFP, Sep. 13, 1925.)

Simple mob violence was not going to be enough to keep neighborhoods segregated, especially when Black Detroiters proved that they were willing to defend their homes. A far more subtle approach developed by realtors was the use of race occupancy restrictions. In the same way that a deed could contain restrictions against certain unapproved buildings being constructed on a lot, it became increasingly common in the 1920s for deeds to restrict occupancy of the land to whites only. In September 1925, just days after the attack on Dr. Sweet's home on Garland Street, the realty firm McGiverin & Haldeman discovered that they had unknowingly sold a restricted lot in the suburb of Huntington Woods to Eugene Moy, a man of Chinese heritage. "When Moy's identity was discovered," the Free Press reported, "the realty concern feared trouble of the same nature which has taken place when Negroes moved into white neighborhoods." Their lawyer took the matter to Oakland County Circuit Court, where Judge Glenn Gillespie issued a permanent injunction preventing Moy from "building on the lot or disposing of it to anyone but a Caucasian." ("Writ Granted To Bar Chinese." DFP, Sep. 11, 1925.)

A 1928 advertisement for Judson Bradway Co., realtors.

Detroit Free Press, Feb. 11, 1928. (freep.newspapers.com)

In 1926, white owners of a two-family flat sued a Black couple, William and FaLena Starks, because they had built a house next door to them and allegedly threatened to move in if they couldn't sell it at a $10,000 profit. Judge Leland W. Carr of the Wayne County Circuit Court barred the Starks from occupying the home at 4114 Lakewood Boulevard because the subdivision restrictions stated that "property shall not be sold nor leased to persons whose ownership would be injurious to the locality." ("Court Upholds Color Barrier." DFP, Jun. 13, 1926.) Although the law couldn't prevent non-whites from owning restricted property, it was willing and able to prevent them from occupying it.

Detail from a 1928 ad for a Windsor subdivision marketed by Detroit's Allan S. McNeil & Co.

Detroit Free Press, Jun. 24, 1928. (freep.newspapers.com)

The real estate industry used race occupancy restrictions to draw white buyers out of the inner city. Detroit's Hannan Real Estate Exchange published a sales manual entitled The Hannan Bible in 1928. In a chapter entitled "Overcoming Sales Resistance," the following example objection and answer are given on page 81:

I can buy property cheaper three miles further in.

Answer. Sure! But look at it! Look at the neighborhood and surrounding tendencies. Are the restrictions such as will safeguard your investment? Or do you just not care who or what your neighbors may be?

Race occupancy restrictions became a popular means of legally enforcible racial segregation both in the suburbs outside of Detroit as well as the newer subdivisions inside the city limits. However, such restrictions weren't always explicitly advertised, but usually only hinted at or couched in soft language. The advertisement for Detroit's Rosedale Park subdivision below warns that residents are restricted to "the type of substantial American citizen that make good neighbors."

Detroit Free Press, July 27, 1924. (freep.newspapers.com)

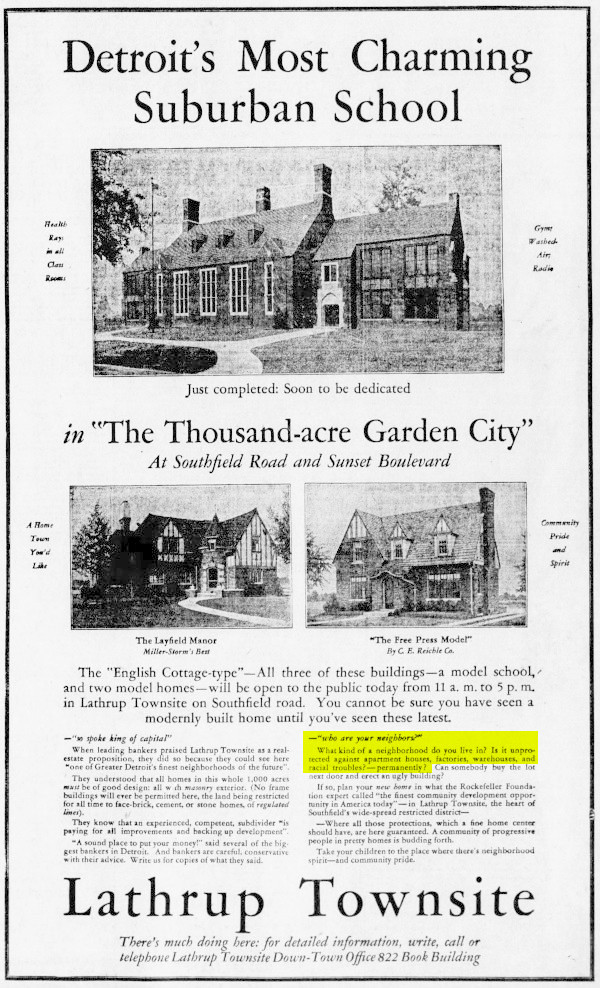

Detroit Free Press, July 27, 1924. (freep.newspapers.com)According to the Lathrup Village Historical Society, property sales in the suburban community were originally restricted to "the North Mediterranean Branch of the Caucasian race." A 1928 advertisement asks, "What kind of a neighborhood do you live in? Is it unprotected against apartment houses, factories, warehouses, and racial troubles? — permanently?"

Detroit Free Press, May 27, 1928. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, May 27, 1928. (freep.newspapers.com)Aside from excluding non-Caucasians, restrictive deed covenants were also used to bar people of lower economic classes by writing minimum construction costs, building sizes, and construction materials into the restrictions. Limiting construction to single-family houses was in itself a barrier to people who relied on a variety of more economical housing options once common in traditionally developed cities.

Dealers in high-class properties took pains to assure buyers of the exclusive nature of their developments. College Park—the group of subdivisions surrounding the University of Detroit—promised to "attract families of the highest type," ensuring "absolute security as to the type of neighbors" found there.

Detroit Free Press, Apr. 27, 1924. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, Apr. 27, 1924. (freep.newspapers.com)Real estate advertisements can tell us a lot about what homebuyers were looking for at the time when the suburban sprawl movement was enjoying its first boom. One of those revealed preferences is made plain by the below advertisement for Livonia's Coventry Gardens subdivision, which assures homebuyers that "the value of your home will never be impaired...by the occupation of any store or dwelling house by persons not of the Caucasian race."

Detroit Free Press, Aug. 2, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, Aug. 2, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)Prominent newspaper advertisements were rarely this explicit, while listings found in the classified section tended to be more direct about restrictions. One 1920 classified ad for Troy's Summit Park subdivision, for example, explicitly states that "no foreigners or negroes" live in the neighborhood. When the prominent west-side realtor, Frischkorn Real Estate Co., was giving away a model home at 11473 Lucerne Street, Redford Township, no restrictions were mentioned in the graphic ads. However, notices of the contest in the classified ads stated that only members of the Caucasian race were eligible to enter.

Left: Detroit Free Press, Jun. 3, 1928. (freep.newspapers.com)

Right: Detroit Free Press, Jun. 24, 1928. (freep.newspapers.com)

When developments targeting working-class homebuyers couldn't promise the same exclusivity as wealthier subdivisions, they sometimes appealed to simple nativist and racial pride with phrases like "English-speaking" and "American neighborhood." Brightmoor—a community established in Redford Township and annexed to Detroit in 1926—was one such development. A 1924 advertisement assures the public that Brightmoor is home to "100% WHITE AMERICAN PEOPLE: English speaking... neighbors with children of the kind you want your children to play with."

Detail from a 1924 advertisement for Detroit's Brightmoor community.

Detail from a 1924 advertisement for Detroit's Brightmoor community.Detroit Free Press, Mar. 30, 1924. (freep.newspapers.com)

Royal Oak's Starr Acres subdivision beckoned homebuyers with the assurance that "more than 75 white American families" had already moved in. Clifford H. Harrison, real estate dealer and president of the Ferndale Board of Commerce, advertised that "good white American neighbors" occupied his community.

Left: Detroit Free Press, Apr. 11, 1926. (freep.newspapers.com)

Left: Detroit Free Press, Apr. 11, 1926. (freep.newspapers.com)Right: Detroit Free Press, Jun. 22, 1924. (freep.newspapers.com)

Incidentally, the office building Harrison constructed for his real estate business in 1922 is still standing at 22822 Woodward Avenue. Today it is a tasting room for the Traverse City Whiskey Company, attached to Como's Restaurant.

Left: (Hathi Trust)

Right: (Google Street View)

Another real estate office still standing a little further down Woodward was that of the Roth Land Company at 18706 Woodward Avenue. The office was made out of two of their model houses, and today is home to the Psychadelic Healing Shack. A version of this model home appears in the ad below, which notes that the company's houses are "Restricted to White Americans Only." The building on Woodward appears to be a mirror image of the version shown in the ad.

Detroit Free Press, Apr. 5, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, Apr. 5, 1925. (freep.newspapers.com)The State of Michigan's 1939 report on subdivisions in metropolitan Detroit discusses restrictions, including race occupany restrictions. The report closely examined the restrictions of record in four townships and found the following percentages of their subdivisions to contain racial restrictions: Dearborn, 66%; Nankin, 32%; Redford, 73%; and Taylor, 63%. Rather than denouncing restrictions, the report complains that "an almost complete lack of coordination between restricted and unrestricted subdivisions" has led to an "effective strangulation of high-class and highly restricted subdivisions by changes in surrounding areas." It warned that restrictions would lose their effectiveness without "some form of official control."

When the Home Owners' Loan Corporation created residential security maps to help determine where loans should and should not be approved, occupancy by non-white persons was officially considered to be hazardous. The Federal Housing Administration's 1938 Underwriting Manual stated:

Areas surrounding a location are investigated to determine whether incompatible racial and social groups are present, for the purpose of making a prediction regarding the probability of the location being invaded by such groups. If a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes. A change in social or racial occupany generally contributes to instability and a decline in values.

The image below shows the distribution of Detroit's Black population in 1940 superimposed over the city's 1939 residential security map.

(detroitography.com)

(detroitography.com)Racial occupancy covenants were ultimately struck down by the US Supreme Court in the 1948 decision, Shelley v. Kraemer, and the Fair Housing Act was intended to outlaw discriminatory lending practices.

Racism, classism, and xenophobia were more than mere anomalies occurring at the dawn of suburban sprawl. The ability to move away from "undesirable" populations and to bar them from following you was one of the intended features of the suburban living arrangement. The demand for racial and class segregation was common enough among homebuyers and realtors that they were included in advertisements, written into deed covenants, and enforced by multiple levels of government.

Closing Thoughts

When confronted with the drawbacks of suburbia, some people feel compelled to call for a revolution in the way we inhabit the land. Should we abandon the evil suburbs—or completely rebuild them as walkable communities? Should Detroit de-annex some of its territory, or consolidate with even more cities? Shouldn't we finally be able to plan and build Utopia because of our science and technology? Well, let us not forget the one lesson that the suburban experiment has taught us, if nothing else: dramatic changes come with dramatic, unforeseen consequences. We will never alleviate suburban problems with suburban planning and building.

The other reason I can't call the suburbs evil is because in 2015 I moved into a single-family home built on an acre in Farmington Hills:

Not pictured: Detroit, Urbanism.

Not pictured: Detroit, Urbanism.Like most worldly endeavors, the suburban experiment was a mixture of good and evil. Building a city of detached homes was supposed to be a scientific way of ensuring that everybody had access to fresh air, sunlight, greenery, privacy, and the economic security of homeownership. Myself and others have benefitted from this living arrangement. I believe that our task now is solving the many unintended consequences and new challenges of our development pattern—land waste, automobile dependency, "missing middle" housing, racial segregation, etc. We will improve our communities, but the solutions won't come from big developers or government programs. I believe these improvements will come from us, the citizens of our communities, through more traditional development methods. As you think about the ways you would like to see your neighborhood change for the better, I would like to leave you with this video about the power of incremental change from Strong Towns.

Wow, outstanding blog. I grew up in the Warwick subdivision built over a filled in gully by McNichols and Lahser.

ReplyDeletePaul - This is first rate scholarship. It totally upends any previous claims that Detroit's population demise was after WWII and the result of neighborhood development outside city limits. I'll be thinking about this for a good long time. Many thanks.

ReplyDeleteThanks for this great research

ReplyDeleteVery good details as usual Paul.

ReplyDeleteI have followed your blog for years. This might be one of your best articles. Kudos!

ReplyDeleteWow, never quite new how blatantly discriminatory housing ads were; they really hit you right over the head in the 20's, huh?

ReplyDeleteI had an slightly related question to ask of you. Do you happen to have the election results of the failed 1958 annexation of the south part of Dearborn Township? I was reading a newspaper article on the attempt to annex the northern part of the township, but it only mentions election results for that failed annexation. The local historical museum wasn't able to find the results for the south township annexation attempt.

Another question: What were the original boundaries of the city when it first incorporated in 1806 and then again in 1815?

DeleteThe 1806 law is kind of vague, basically saying that everything surveyed in the separate law instituting the Woodward Plan was part of the city. That would make its limits west of Randolph, east of Cass, and south of Adams. Honestly I'm not sure about the 1815 borders. One day I do want to go back and start a series on all annexations from the beginning!

DeleteThank you for this fascinating article. I think it's your best one yet. I had no idea that the suburban sprawl initiating urban decay had already begun in the 1920's. It appears that our large urban centers were doomed from the moment the Highland Park Ford Plant began cranking out the Model T's.

ReplyDeleteIt is an informative post. Interested in investing in Pre-foreclosures in United States? RealEstateCake is the best property platform for getting the exclusive real estate deals online in entire United States.

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing this helpful post. Discover the best Home for Sale in Alabama deals online in Alabama, United States with the Residential Alabama.

ReplyDeletePaul, I stumbled on your blog over the weekend and I'm completely amazed at the research you've done. I'm an urban planner who's originally from Detroit (now in the Chicago area) with a blog of my own. It started in 2012 with a post I called Reasons Behind Detroit's Decline (https://cornersideyard.blogspot.com/2012/02/reasons-behind-detroits-decline.html) that I later developed into a series (https://cornersideyard.blogspot.com/2015/01/the-reasons-behind-detroits-decline_6.html). If you look at my stuff you'll see we took different research approaches but came up with very similar conclusions. I'd love to talk directly with you and share notes! I followed your Detroit Urbanism Twitter; if you follow back we can DM each other and share emails. Hope to hear from you!

ReplyDeleteThis log is incredible. Amazing work!

ReplyDeleteThank you for your work on documenting Detroit's history. I learned so much from your report here. Spectacular work.

ReplyDelete