In this series on the City of Detroit border, we are breaking the city limits down into segments and uncovering the history behind them individually. The previous post covered the border from Windmill Point to Mack Avenue, 233 feet east of the center of Alter Road. Continuing from where we left off, the border runs down the center of Mack, 1.3 miles east to the center of Cadieux Road. This line is also the north border of the City of Grosse Pointe Park.

The short answer as to why the border is here is because the city annexed land from Grosse Pointe Township in 1917. The territory added to the city that year is represented by the light green shape circled below in this image of Detroit annexations until 1926:

(Detroitography)

(Detroitography)The events leading up to this annexation are related to a now-defunct village—long since absorbed into the city—represented by the small yellow rectangle labeled "1918," also found inside the red circle in the map above. This is where our story begins.

The Village of Saint Clair Heights

Detroit Free Press, Oct. 2, 1892. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, Oct. 2, 1892. (freep.newspapers.com)Detroit was blossoming as a city of industry in the late 19th century. As a result of its growth and success, the city physically expanded in 1891, moving its eastern border from about where Townsend Street is today to just west of Bewick Street. The extension of city services that followed presented an opportunity for Detroit's real estate investors, who knew there was a market for low-tax suburban homes with city conveniences.

George M. Hendrie, owner of the Detroit Street Railway Company, had purchased much of the former Bresler farm, located in Grosse Pointe Township immediately outside of the newly extended Detroit city limits. In May 1891, he subdivided part of the farm between Mack and Jefferson avenues, and named the development Saint Clair Heights. By the end of 1891, Hendrie had sold his Detroit Street Railway Company to the Detroit Citizens' Street Railway Company, which would extend their newly electrified service to the city limits—and thereby to his suburban land holdings—in a little more than a year. Hendrie, along with other real estate investors, formed the Saint Clair Heights Syndicate in 1892, and then personally sold to the corporation 154 acres of the Bresler farm, lying between Mack and Harper. The Syndicate, represented by trustee Eugene H. Sloman, subdivided this land in April 1893, also naming it Saint Clair Heights. This subdivision formed the nucleus of the future village which would go by the same name.

Advertisement from the May 28, 1893 edition of the Detroit Free Press. (freep.newspapers.com)

Advertisement from the May 28, 1893 edition of the Detroit Free Press. (freep.newspapers.com)Saint Clair Heights was in fact a streetcar suburb, accessible by Detroit Citizens' Railway Company cars on Mack and Gratiot avenues. Knowing that the development was utterly dependent upon this service, Sloman gained the company's assurance that fares to the city limits would be capped at five cents. He also convinced the Detroit Water Works to extend service to the development, and the syndicate paid to lay the first water mains.

Eugene Hugo Sloman (Hathi Trust)

Traditionally, real estate dealers simply divided vacant land into city lots and sell them, whether to speculators, investors, or builders. The Syndicate, however, had a more novel approach. Helping to create the illusion that moving to a subdivision in a corn field at the edge of town was a good idea, the Syndicate built 100 houses, designed by Detroit architects George D. Mason and Zachariah Rice, throughout the rural subdivision. A newspaper reporter, visiting the construction in May 1893, remarked, "Every statement that has appeared in print sinks into insignificance when compared with the actual work already done and now taking place on this wonderful subdivision. We say wonderful because the changes which are taking place seem to have been accomplished by the work of magic." ("At St. Clair Heights." Detroit Free Press, May 28, 1893) The homes were given away "free" by drawing names of the owners of the 734 lots which sold by August, at $300-$350 each. An additional 42 houses were contracted for the following spring.

A model home, pictured in the May 21, 1893 edition of the Detroit Free Press. (freep.newspapers.com)

A model home, pictured in the May 21, 1893 edition of the Detroit Free Press. (freep.newspapers.com) According to Benjamin Gravel of the Historical Detroit Area Architecture Facebook group, this is one of the model homes designed by Mason & Rice.

According to Benjamin Gravel of the Historical Detroit Area Architecture Facebook group, this is one of the model homes designed by Mason & Rice. An early Saint Clair Heights home, on Montclair Street.

An early Saint Clair Heights home, on Montclair Street.Who needs taxes?

Ten years after the first houses were built, the development's shine was probably beginning to dull. Sewers and sidewalks were incomplete, there was minimal law enforcement, and the townships simply did not offer services like fire protection or street paving. In order to raise the taxes necessary for basic services, Saint Clair Heights had to incorporate as a village. In October 1903, the Michigan legislature approved the incorporation of an area centered on the original subdivision, covering about one square mile. About 400 people called Saint Clair Heights their home.

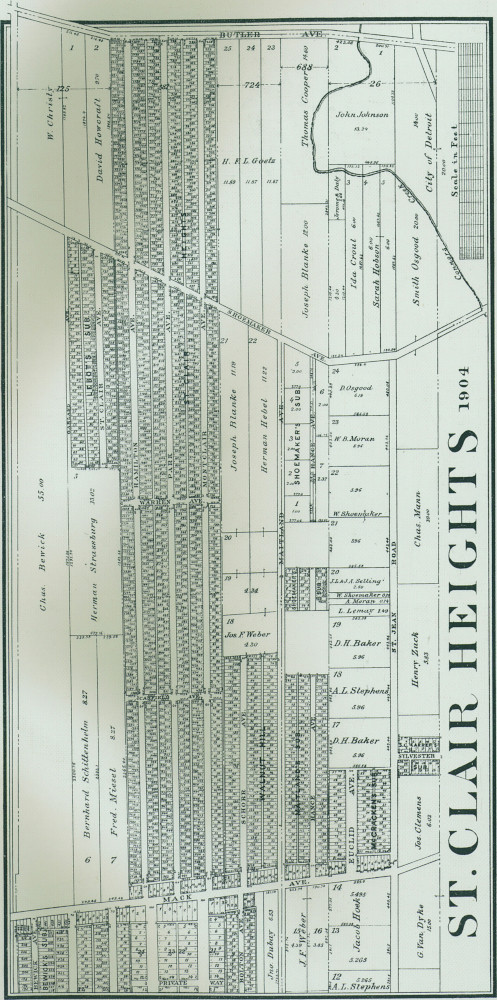

This map of St. Clair Heights appears in a 1904 Wayne County real estate atlas.

(University of Michigan)

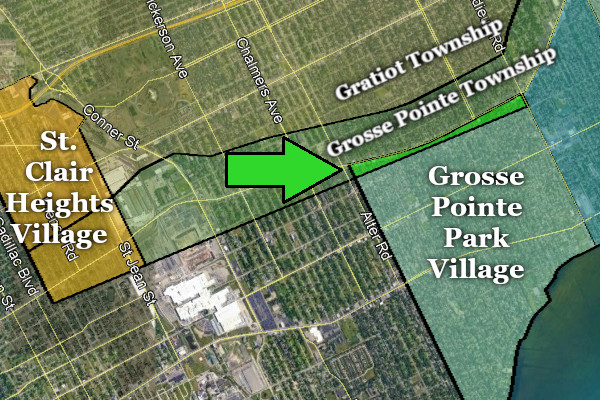

Incidentally, when Saint Clair Heights was incorporated, it straddled the border between Grosse Pointe and Gratiot townships, which were once a single unit. The Michigan legislature divided them on May 16, 1895 with the passage of Act 412 of 1895, declaring that the boundary between them is a line drawn ten rods (1,650 feet) north and west of the center line of Mack Avenue. By the time Saint Clair Heights was incorporated in 1904, the villages of Grosse Pointe, Grosse Pointe Farms, and Fairview had already been established in Grosse Pointe Township. The image below shows where those borders would be today.

The Suburban Experiment

Saint Clair Heights baseball team circa 1914, perhaps at Mack Park. (Ebay)

Saint Clair Heights baseball team circa 1914, perhaps at Mack Park. (Ebay)Saint Clair Heights was eager to invest in civic improvements, and there were plenty to be made. Village voters approved $37,000 in bonds for water main and sewer construction in late 1904, and a year later their sewers were connected to Detroit's system. Public safety was lacking, and street lights were still years away. As late as 1905, homes had to be lit with oil lamps because the entire village was still without electricity ("Suburban siftings." Detroit Free Press, Oct. 19, 1905), and gas mains were not laid until 1914 ("Gas franchise given in St. Clair Heights." Detroit Free Press, Oct. 3, 1914). The very first electric street lights were installed in June 1907.

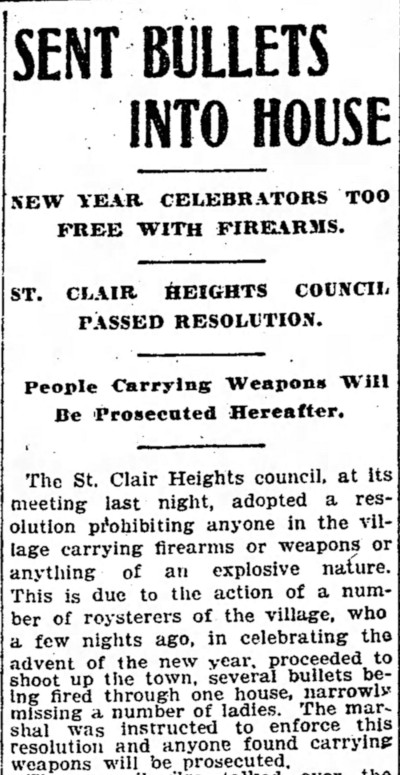

Detroit Free Press, Jun. 23, 1905. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, Jan. 7, 1905. (freep.newspapers.com)

The village government struggled to serve its population, which had climbed to 1,252 by the time of the 1910 US Census. In 1911, when voters were asked to approve an additional $20,000 in bonds, the Detroit Free Press noted: "Although the village has been to great expense and has made many improvements in the last few years, the growth in population has been very large and the improvements have not kept pace with the influx of people." ("May bond for $20,000." Detroit Free Press, Sep. 8, 1911.) Investments in public safety were also needed. When the village fire department failed to put out a fire without assistance from Detroit, the Free Press reported, "St. Clair Heights is poorly equipped to fight fires, having only a hand engine and a feeble chemical [engine]... The one hydrant available was on Mack avenue, nearly 1,000 feet away, and street car traffic was tied up by the hose across the track." ("St. Clair Heights flats are burned." Dec. 11, 1912)

Detail from a 1905 topographic map of Grosse Pointe Township.

Detail from a 1905 topographic map of Grosse Pointe Township.(USGS Historical Topographical Map Explorer)

Sidewalks and crosswalks were sufficiently completed by 1913 that the local postmaster allowed door-to-door delivery of mail in the village for the first time. Mack Avenue, as well as all north-south streets, were fully paved by the end of 1914 (although the work was briefly suspended when it was discovered that the highway fund was somehow overdrawn). The few primitive electric arc lamps on Mack Avenue were replaced by a more modern street lighting system, switched on with some fanfare at 8pm on October 10, 1914. Additional bonds were approved, and the construction of sewers, streets and schools continued. A census of the village in November 1915 showed a 500% increase in just five years, to 6,853 people.

The William E. Hutchinson School, constructed in 1917 for the Village of Saint Clair Heights.

The William E. Hutchinson School, constructed in 1917 for the Village of Saint Clair Heights.From all outward appearances, Saint Clair Heights appeared to be a success story. At least, as long as its population didn't stop growing and the construction crews didn't stop building. But in reality, the village was an early example of our notoriously unsustainable American suburban development pattern. Saint Clair Heights was after all an experimental marketing scheme, not an actually prosperous village, which it was trying to emulate. In order for it to continue to exist, it had to "grow" by annexing more land and attracting new developments, so that tax revenue could maintain infrastructure in the older part of town that the municipality never had the means to support in the first place. City planners call this the Growth Ponzi Scheme.

Room to "Grow"

This 1904 map has been colorized to show political boundaries in 1916.

This 1904 map has been colorized to show political boundaries in 1916.(University of Michigan)

The process for changing municipal boundaries changed since the time that the Michigan legislature annexed most of Fairview to Detroit. The 1908 state constitution empowered voters in cities and villages to "pass all laws and ordinances relating to ... municipal concerns," including the alteration of borders. The following year, the state enacted the Home Rule Village Act (Public Act 278 of 1909) and the Home Rule City Act (Public Act 279 of 1909), which prescribed annexation processes which cut the legislature out of the process completely.

(Hathi Trust)

Under the new law, the annexation process began with collecting signatures from voters in the municipality that is taking on land, as well as within the township from which the land was being annexed, with certain prescribed minimums. Petitions were to be delivered to the county board of supervisors, who would inform the county clerk to place an annexation proposal before voters the next general election.

Petitions to annex the parts of Gratiot and Grosse Pointe townships—between the eastern edge of Saint Clair Heights and Alter Road—were circulated as early as May 1914. ("St. Clair Heights may annex some territory." Detroit Free Press, May 27, 1914.) It's not certain whether it was the same petition drive or a separate one, but it wasn't until 1916 that enough signatures were collected that the petitions were brought before the Wayne County Board of Supervisors, who authorized the annexation proposal for the 1916 spring election. If it passed, village taxes could be levied upon the industrial district growing up along Mack Avenue in Grosse Pointe Township, including the Lozier Motor Company plant, as well as the site where construction had just begun on a 222,000 square foot facility for the Michigan Stamping Company.

The Lozier Motor Co. built this office and factory in Grosse Pointe Township, about 250 yards east of the Saint Clair Heights village limits, in 1910. Six years later the property was sold to the Motor Products Corp.

The Lozier Motor Co. built this office and factory in Grosse Pointe Township, about 250 yards east of the Saint Clair Heights village limits, in 1910. Six years later the property was sold to the Motor Products Corp.(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

St. Clair Heights lies just west of the Michigan Stamping Company factory on Mack Ave., circa 1920.

St. Clair Heights lies just west of the Michigan Stamping Company factory on Mack Ave., circa 1920.(Detroit Historical Society)

The clerks for Gratiot and Grosse Pointe townships ensured that the annexation proposal appeared on ballots for the May 24, 1916 election for both township and village voters. Some officials in Detroit were wary letting the village taking on more territory. "City Engineer [Robert] McCormick, of Detroit, discourages the annexation plan, declaring that the sewer facilities at the east end of the city are insufficient to drain the extra territory." ("Suburban villages active with elections." Detroit Free Press, May 24, 1916.)

Grosse Pointe Park Annexation Proposals

Meanwhile, in the Village of Grosse Pointe Park, voters were deciding whether to annex another part of Grosse Pointe Township. This annexation would in fact form part of the Detroit city border along Mack Avenue that we know today. According to the Detroit Times of April 13, 1916, "Grosse Pointe Park wants to take in a 500-foot strip on the south side of Mack ave., to prevent residents there from tapping the village water main without permission." The proposal passed.

Proposed annexation to Grosse Pointe Park Village, May 24, 1916.

Proposed annexation to Grosse Pointe Park Village, May 24, 1916.Before, the village's north border was the same as that of Fairview.

Petitioners acted quickly, placing a second annexation proposal before Grosse Pointe Park voters before the year was out. This time the village sought to double its size by taking on two square miles from Gratiot and Grosse Pointe townships. Election notices describe the bounds of the proposed addition being: the center line of Mack Avenue, a line 233 feet east of the center of Alter Road, the north line of Harper Avenue, and the center line of Cadieux Avenue.

Proposed annexation to Grosse Pointe Park Village, November 7, 1916.

Proposed annexation to Grosse Pointe Park Village, November 7, 1916.The measure failed to pass at the fall election of November 7, 1916. The Detroit Free Press reported: "The Grosse Pointe Park village proposal to annex small strips [sic] of territory in Grosse Pointe and Gratiot townships, was defeated in both townships and the village, very few votes being cast because of lack of interest." ("Voters adopt 4 annexation plans; 3 lose." Nov. 11, 1916)

St. Clair Heights Annexation...Passes?

Saint Clair Heights voters overwhelmingly approved of the new addition to their village at the May 24, 1916 election, as did most voters in Grosse Pointe Township. However, within the lightly populated annexation area, only nine votes were cast, and all were against the proposition. In Gratiot Township, outside of the annexation area, 31 votes were cast, and 30 were opposed. This led to some confusion, having to do with the differences between the annexation laws for cities and villages. When a city annexed land, the law said that ballots within the city, the annexation area, and the remaider of the township from which the land was being taken had to be kept separate, and that a majority of all three was required to pass. But the village annexation didn't make this distinction. Could the village annex territory where not a single voter approved of the change?

Michigan's Secretary of State, Coleman C. Vaughan, sought the opinion of Michigan Attorney General Grant Fellows on the matter. Fellows pointed out that the letter of the law only calls for a simple majority of all votes from the village and both townships combined in order to pass. Whether or not the process was different for cities was inconsequential. Therefore, the annexation carried.

"Not so fast."

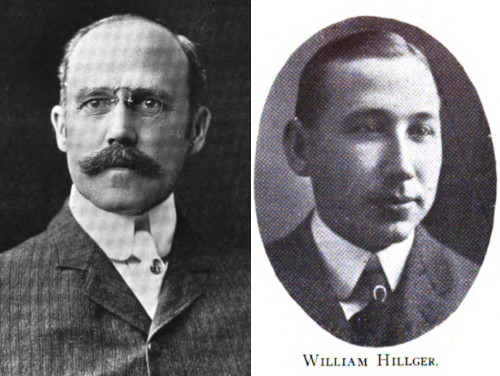

Left: Daniel J. Campau (Hathi Trust)

Right:William Hillger (Hathi Trust)

Detroit experienced an extremely steep growth in population in the 1910s as workers from around the world flocked to its factories. The city's real estate men made fortunes off of the unprecedented demand for new housing, and they weren't going to just sit there and watch while a village took over land that would sell for much more if it instead fell within the city limits and received city services.

Two prominent Detroit real estate dealers, Daniel J. Campau and William Hillger, sued to stop the annexation from proceeding. Campau owned hundreds of acres in and around the annexation area. Joining them were George Pfent, the Gratiot Township supervisor; and Stephen Corby, who also owned land within the affected territory. Judge Alfred J. Murphy issued a writ of certiorari ordering the secretary of state, the Wayne County clerk, and the clerks of the two townships to produce their records in court on February 3, 1917.

The real estate men didn't stop there. Hillger at that point was already circulating petitions in Detroit, Gratiot and Grosse Pointe calling for an annexation of about eight square miles from the townships to the city, including all of the territory Saint Clair Heights was attempting to take in and more. Hillger's petition drive ultimately netted about 50,000 signatures.

William Hillger's 1917 proposed annexations to Detroit.

William Hillger's 1917 proposed annexations to Detroit.Hillger knew the area intimately well. He was born in Grosse Pointe Township in 1869, on a farm where his German immigrant parents had settled in the 1850s. He was elected to the Detroit Common Council in 1900, representing the city's seventeenth ward for ten consecutive years. In that time he fought to reform streetcar service and played an active role in the annexation of Fairview, his home territory. He founded the William Hillger Real Estate Company in 1904 and eventually became one of the most successful realtors in the city, having sold out multiple subdivisions in Fairview, Grosse Pointe, and throughout the east side.

Detroit Times, July 26, 1909. (Library of Congress)

Excerpt from a full-page advertisement for the the Sherrard Subdivision, southwest of Mack and Alter.

Excerpt from a full-page advertisement for the the Sherrard Subdivision, southwest of Mack and Alter.Detroit Times, June 19, 1915. (Library of Congress)

Hillger's company was the listing agent for this subdivision, which lay within his

Hillger's company was the listing agent for this subdivision, which lay within hisproposed annexation area. Today it is part of the East English Village neighborhood.

Detroit Times, Oct. 30, 1916. (Library of Congress)

Case is Heard

After the various clerks had turned over the annexation documents to Wayne County Circuit Court, Judge Murphy set a hearing for February 13, before visiting circuit Judge Nelson Sharpe. The county board of supervisors had scheduled a meeting later that month to discuss various business, including annexation proposals, and all parties were apparently eager to resolve the court case before that meeting. Following the February 13 hearing, the Detroit Free Press reported:

That the annexation of territory of Gratiot and Grosse Pointe townships to St. Clair Heights is being opposed by a small group of Detroit men, who are plotting the territory for commercial purposes, was the contention of Attorney J. H. Pound in Judge Sharpe's court Wednesday. The case was taken under advisement by the judge. (...)

Attorneys Orla B. Taylor and William Van Dyke attacked the constitutionality of the state law which permits a majority vote of the whole district affected for affirmation. They declared the "home rule" law makes provision for a majority affirmation in the territory to be annexed as well as in the annexing territories.

("Says real estate men halt merger." Detroit Free Press, Feb. 15, 1917)

In addition to attacking the constitutionality of the Home Rule Village Act, plaintiffs "assert(ed) that there are several other reasons why the annexation was invalid, one of which was the fact that women were not allowed to vote." ("Validity of annexation is question for court." Detroit Free Press, Jan. 27, 1917) This reason was probably disingenuous, since there were few instances in which women in Michigan were allowed to vote at the time anyway (e.g., school board elections). Ultimately, every argument offered by the plaintiffs were ignored except one: the Home Rule Village Act required that annexation election notices be published four times before the vote, but in this case only three notices were published. In his judgment of February 16, 1917, Judge Sharpe annulled the Saint Clair Heights annexation.

The Wayne County Board of Supervisors reportedly considered placing the Saint Clair Heights annexation proposal on the ballot a second time at their February 19 meeting. ("Will reconsider St. Clair addition." Detroit Free Press, Feb. 18, 1917.) Ultimately, however, Hillger's annexation proposals were accepted without opposition, and the board instructed the county clerk to put the initiative before voters at the following election on April 2. ("Vote is called on annexation." Detroit Times, Feb. 20, 1917.)

The 1917 Spring Election

Detroit Free Press, March 23, 1917. (freep.newspapers.com)

Detroit Free Press, March 23, 1917. (freep.newspapers.com)Hillger and Campau weren't taking any chances. They published not just four, but five election notices, each bearing the name of their attorney, William Van Dyke, and containing every necessary detail that voters needed to know. Gratiot Township electors living outside of Saint Clair Heights were instructed to vote at "the Grove Gun Club Shooting house on Gratiot Avenue near Grotto Road." It would be hard for anyone seeing these notices in any Detroit newspaper at the time to miss the multiple articles about the city's unprecedented growth, stories regarding the impending housing crisis, advertisements for subdivision lots among the farms on Detroit's periphery, and frequent editorials calling on the city to expand.

PIPER FAVORS ANNEXATION

Thinks District On East Side Will Be Made Part of City By Big Vote

Detroit Times, Mar. 31, 1917

Walter C. Piper, a member of the annexation committee which represents property owners in a district on the east side bounded by Grosse Pointe village, the Seven-Mile-rd, and Hamtramck, says that there is every indication that the vote on annexation of this territory to the city will carry by an overwhelming majority.

"To gain the benefit of the big sewer and boulevard extension plans this section must be annexed," says Mr. Piper. "The proposed appropriation of $8,000,000 for the sewer extension work was made with the idea of giving this section these improvements, and if it is not annexed the improvements will be diverted to other sections of Detroit.

"I do not own any property in this district but I am heartily in favor of annexation wherever feasible, and I believe that this territory should be made part of the city."

Mr. Piper confidently believes that Detroit will extend its limits to the county line [Eight Mile Road] on the east some day.

Although the article doesn't mention it, Piper was president of the National Association of Real Estate Boards and the Detroit Real Estate Board.

Detroit Times, February 5, 1917. (Library of Congress)

Detroit Times, February 5, 1917. (Library of Congress)Turnout was unusually light at the spring election. "The wild mixture of April showers, snow-sleet storms that were practically continuous during the day, put a decided damper on the voting throughout the city," according to the Detroit Free Press. "Members of the election commission said the election was the most uneventful one in the city's history." ("Half of votes cast in storm." Apr. 3, 1917)

Despite low voter participation, the report of the Wayne County Board of Canvassers was not complete until April 18. It showed that Detroit voters favored the Gratiot Township annexation by 40,972 to 8,268, and the Grosse Pointe Township annexation by 38,728 to 7,817. In Gratiot Township, voters supported annexation by 136 to 71 within the affected area, and 196 to 64 in the rest of the township. Grosse Pointe Township favored the proposal by 96 to 19 within the annexation area, and 388 to 271 outside. ("Canvass shows annexations win." Detroit Free Press, Apr. 19, 1917.) The board of canvassers filed their certificate of the election results and the annexation proceedings in the office of the Secretary of State on April 23, 1917, thereby finalizing the annexation and legally incorporating the territory as part of the City of Detroit as of that date.

Description of area annexed to Detroit from Grosse Pointe Twp., appearing in a pre-election notice. Highlighted portion is now part of the city's border.

Description of area annexed to Detroit from Grosse Pointe Twp., appearing in a pre-election notice. Highlighted portion is now part of the city's border.Detroit Free Press, Mar. 23, 1917. (freep.newspapers.com)

With the sudden changes brought about by annexation, government officials were sometimes unprepared for the resulting legal quandries involving school districts, city services, and law enforcement. On April 21, 1917, Detroit police officers raided the Belgian Club, located in an old city-owned tuberculosis sanitarium at Harper Avenue and Connors Creek Road. They "arrested 28 men, and confiscated 35 gamecocks, 50 cases of beer, a cash register, $5.95, a pair of scales, a cloth used to cover a faro table and several pairs of spurs." ("Cockfighting in pest house." Detroit Free Press, Apr. 23, 1917) However, when the men appeared in the court of Justice Albert F. Sellers, he dismissed the charges because the raid occurred two days before the annexation proceedings were filed with the Secretary of State, and therefore the territory was legally part of Gratiot Township at the time of the raid. ("Lack of jurisdiction saves 'cockfighters'." Detroit Free Press, Apr. 26, 1917.) The city's prosecuting attorney faced a similar connundrum when he attempted to file charges against five saloonkeepers in the newly annexed territory who kept their doors open on Sunday, April 21, which would have been in violation of the city's liquor laws, had the saloons been within the city limits on that day. ("'Booze' violations puzzle Jasnowski." Detroit Free Press, Apr. 27, 1917.)

The End of a Village

Following Hillger's successful annexation campaign, Saint Clair Heights found itself surrounded by Detroit on all sides, just as Hamtramck and Highland Park are today. Cut off from the rest of Gratiot and Grosse Pointe townships, far from being financially independent, and without room to "grow," the village ultimately accepted the inevitability of annexation. The idea had in fact been discussed for more than a decade. A petition to join Detroit was circulated in the village as early as 1907, and the state legislature even considered annexing Saint Clair Heights to Detroit at the same time that most of Fairview was added to the city. In a 1913 sermon, Reverend Harold E. Goodenow, the young minister of Saint Clair Heights Methodist Church, told his congregation in a 1913 sermon: "What this suburb needs is annexation... We are really part of the city now, and might as well have its benefits. We need better police and fire protection, better lighting, mail deliveries to our homes, paved streets and a drainage system and all these good things and many more will come with annexation. We have everything to gain and nothing to lose." ("Local siftings." Detroit Free Press, Apr. 21, 1913.)

A Saint Clair Heights home today.

A Saint Clair Heights home today.

In late 1917, several village authorities came under investigation for corruption involving the purchase of a site for an incineration plant. Indictments followed in January 1918. When the village held a mass meeting in February to discuss annexation, the village attorney was hooted when he tried to speak against the idea. Every village official under investigation was voted out in the spring election of March 11, 1918, and replaced by candidates who pledged to pursue annexation to Detroit. The village's new attorney, Anthony Maiullo, circulated petitions in support of the merger, which had received a enough signatures by June to call for the ballot measure.

On August 27, 1918, voters in every affected municipality approved of the annexation by wide margins: Detroit, 50,800-8,366; Graiot Township (outside the village), 26-10; Grosse Pointe Township, 205-122; and Saint Clair Heights, 598-166. Annexation proceedings were filed with the county clerk and the Secretary of State on October 1, 1918, and the Village of Saint Clair Heights ceased to be. Upon annexation, village property became city property, including the brand-new village fire hall, which was converted by the city into a recreation center..

On the Sunday following the election, 3,500 ex-villagers marched in an annexation victory parade (which ended up doubling as a Liberty bond drive), complete with the Liberty marching band, and women in native Belgian costume bringing up the rear. There were speeches in what is now called Brewer Park, songs by the sixty-member Girls' Liberty chorus, and the raising of a huge silk American flag gifted to Detroit's newest neighborhood, on a flagpole just installed on Mack Avenue. The village happily assimilated to the city, and the city was still prosperous enough to easily absorb a struggling village.

Why was Saint Clair Heights not able to make it as an independent municipality? Throughout most of history, villages and cities grew slowly over the course of time, with many individuals making small investments. It used to take multiple generations, weathering multiple economic booms and busts, for communities to amass enough wealth to build substantial homes and complex infrastructure. Then came along the suburban development pattern, in which entire neighborhoods would be built to a finished state. Why wait generations when you can just construct all of the buildings, sewers, etc. right now? We are so used to this way of thinking that it's easy to forget how new it is, and even how revolutionary it must have seemed when Eugene Sloman envisioned building a village from scratch in the fields of Grosse Pointe Township in 1893. The suburban development pattern would be copied countless times hence as Detroit annexed and developed more than one hundred square miles of rural land between 1906 and 1926.

Facing east down Mack Avenue, 0.4 miles east of Saint Clair Heights, in 1910.

Facing east down Mack Avenue, 0.4 miles east of Saint Clair Heights, in 1910.This land would be annexed to Detroit seven years after this photo was taken.

(Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library)

Facing west down Mack Avenue from Saint Jean Street, 1932.

Facing west down Mack Avenue from Saint Jean Street, 1932.(Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University)

The Suburban Experiment, Again

The real estate companies subdivided one farm after another through the newly annexed strip of Grosse Pointe Township as the seemingly endless demand for building sites pushed development eastward. Detroit made substantial investments in this area in the early 1920s, having rebuilt Conner's Creek as a sewer, obtained the land for what is now Chandler Park, and paved stretches of Harper and Warren avenues. But there was an even more pressing need for homebuyers, according to realtor Arthur J. Scully, quoted in a 1923 story in the Detroit Free Press:

"There are between 1,500 and 1,800 families in this section without street car service and hundreds of lot owners are deferring building until provision for transportation is made. Several public meetings have been held with the street railway commission and the common council and construction of the Warren avenue line has been assured.... With better roads, new schools, adequate sewer system, a beautiful park and, most important, sufficient street car service the eastern section of Detroit should find its way to a place among the leaders in the program of expansion and progress."

("Eastern section of Detroit shows new development." Detroit Free Press, May 13, 1923.)

(freep.newspapers.com)

(freep.newspapers.com)Contractors could hardly build enough beautifully crafted brick homes in the ensuing building boom. Entire neighborhoods were practically built to a finished state, along with all of the infrastructure that they required. Nothing could possibly go wrong.

When the stock market crashed in October 1929, a gigantic real estate bubble burst along with it. New home construction collapsed by 95 percent as financing disappeared. In just three years, homes would lose 35% of their value, and up to half of US mortgages would end up in default. Nobody could buy, sell, or build. The real estate market's perpetual money-making machine was broken.

William Hillger suffered a nervous breakdown in 1931 and had reportedly received treatment at a sanitarium. Tragically, on Saturday, May 28, 1932, Hillger died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound at the age of 64, in his company's office at 11621 East Jefferson Avenue. Only a storm water retention pond exists on that spot today. Hillger Avenue, which used to run through Fairview and Saint Clair Heights, has been almost completely obliterated by industry. A dead-end, weed-strewn stub is all that remains.

Hillger Street, Detroit. (Google Street View)

Hillger Street, Detroit. (Google Street View)The legacy which Hillger has left us are the attractive bungalows and tree-lined streets found throughout the neighborhoods he developed, such as Detroit's Jefferson-Chalmers neighborhood. Along the border which Hillger helped define is a neighborhood once known as East Warren, where thousands of sturdy homes inspired by English architecture sprang up in the Roaring Twenties. In 1990, the section east of Outer Drive renamed itself East English Village. Four years later, the community west of Outer Drive adopted the name Morningside. However we may fault the best laid plans of real estate developers of nearly a century ago, they did at least provide a medium for Detroit architects, masons, and other artisans whose love of beauty for its own sake is self evident.

A home in East English Village, Detroit.

A home in East English Village, Detroit.(Wikipedia)

Post Script - Scenes Along the Border

As seen in the previous post, the photo above shows the legal northwest corner of the City of Grosse Pointe Park, lying in the center of Mack Avenue. The Hillger annexation line runs east down the center of Mack from this point to the center of Cadieux Road. The border doesn't bisect any property or create any other anomalies.

Lost River Tiki, 15421 Mack Avenue, Detroit.

Lost River Tiki, 15421 Mack Avenue, Detroit. All Star Books (now closed), on Mack Avenue near Bishop Street, Detroit.

All Star Books (now closed), on Mack Avenue near Bishop Street, Detroit. The Detroit side of the border, Mack Avenue at Three Mile Drive.

The Detroit side of the border, Mack Avenue at Three Mile Drive.Below is a photo of Grayton Street, facing south from Mack Avenue. Grosse Pointe Park closed Grayton and Somerset streets at the Detroit border in 1984. ("Dead end: The Park turns around old idea." Detroit Free Press, Dec. 13, 1984)

To explore the political boundaries discussed in this post in more detail, click here to download Borders2.kmz and open the file in Google Earth.

Great Work once again!

ReplyDeleteWowie! What a great post. Things get a little confusing/mixed up after St. Clair Height's attempt to annex in Grosse Pointe and Gratiot Townships fails, though:

ReplyDelete"The Wayne County Board of Supervisors reportedly considered placing the Saint Clair Heights annexation proposal on the ballot a second time at their February 19 meeting."

Is this line talking about Detroit's attempt to annex the area the village was trying to annex (and then some)? Or is this talking about the Board wanting to put St. Clair Height's annexation of the township land back before voters?

We know that by April 23, 1917 the village's attempt to annex land officially died. But when did Detroit's annexation attempts of land in the townships outside the village start? It seems like it was shortly before the village's attempt died, but I'm not sure.

Also, coming back to this, I wonder what the reasoning was behind "ten rods (1,650 feet) north and west of the center line of Mack Avenue"? I imagine this was mainly to keep the road entirely with Grosse Pointe Township. But I wonder what ten rods equalled back then for them to have chosen that number, like, what was the typical lot size they were thinking about and what kind of development were they thinking about that they pushed the boundary back from the road 10 rods?

DeleteThanks! Yes, I did have a tough time trying to explain the order of events. Let me try to re-explain the contents of the sentence you quoted. The board of supervisors were planning a meeting for February 19, and before that meeting happened they were willing to put St. Clair Heights' proposed annexation on the ballot again, since the only reason why the court rejected it was because only three election notices were published instead of four. Since the petitions and other documents were still okay, they were reportedly thinking about having that question appear on the next ballot. However, Hillger's petitions to annex all of that land an more were also ready, and the board of supervisors were aware of his petition. From reading every news story I could find about this, I get the sense that the board basically had to choose between the two. The SCH annexation being nullified in court didn't necessarily preclude it from going back on the ballot and giving the clerks another chance to print the right number of notices.

ReplyDeleteHonestly, I think that sentence is worded strangely because I cite it with a news story that has the word "reconsider" in the headline, and I was trying to not use that word in the sentence haha...

To answer your last question (when did Detroit's annexation attempts of land in the townships outside the village start), the real estate men had started the petition process at least by February 1917, although it may have started earlier, but that's the first I saw it mentioned in a news story. Whether it was intentional or just destiny, Hillger and Campau's actions were perfectly timed to knock out SCH's annexation attempt and butt in with their own. I hope this makes more sense!

Paul, I went back and read it again, and this all makes complete sense.

DeleteBoy, what I wouldn't give to have been at that February 19 meeting of the Board of Supervisors and hear why they didn't take back up St. Clair Heights' annexation attempt along with the opposing Detroit annexation proposal. I'd not be surprised there was all kinds of backroom deals had that day (or probably before that) to muscle St. Clair Heights' proposal out the way. I'd also be interested in why St. Clair Heights didn't sue the board of supervisors for not placing their second attempt on the ballot.

BTW, went and looked up the Home Rule Villages act to see what it now says about annexation (http://legislature.mi.gov/doc.aspx?mcl-78-5), and the funny thing is that it was amended to add that every affected community in the district for annexation each had to give a majority vote for it to pass, just like the law for cities. Makes me wonder if this case spurred that amendment? It looks like the first time it was amended was in 1919, which is really close to this case.

I’m following the suggestions as mentioned in your blog found this blog which is related to my interest. The way you covered the knowledge about the subject and

ReplyDeletewas worth to read, it undoubtedly cleared my vision and thoughts towards 3 BHK flat in kolar road

Your writing skills and the way you portrayed the examples are very impressive. The knowledge about Best Builders In Bhopal

is well covered. Thank you for putting this highly informative article on the internet which is clearing the vision about who is making an impact in the real estate sector by building such amazing townships and 6 bhk duplex in hoshangabad road

Great work. Do you know where the municipal building or buildings were located prior to annexation?

ReplyDeleteCarlton, got interested in this myself and went online to review some old Free Presses. It's strange, but there isn't really much mention over the village hall, except to say that a new one was built in 1912, or at least planned then and completed the following year. Anyway, it was at Lemay and Canfield, but which corner I'm unsure of it. Upon annexation to Detroit in 1918, and old article mentions that the village hall was going to be turned into a community center for a larged planned park. Today there is a planned park near this intersection called Brewer.

Delete