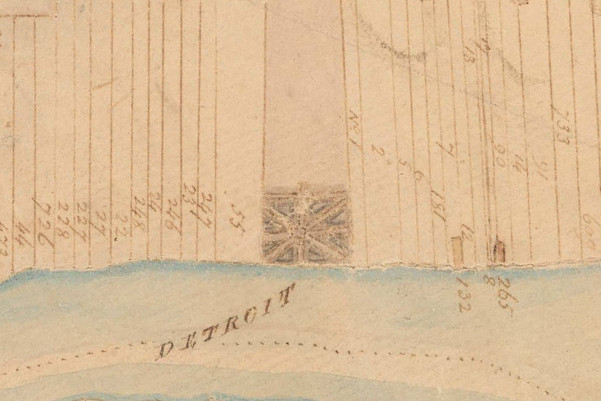

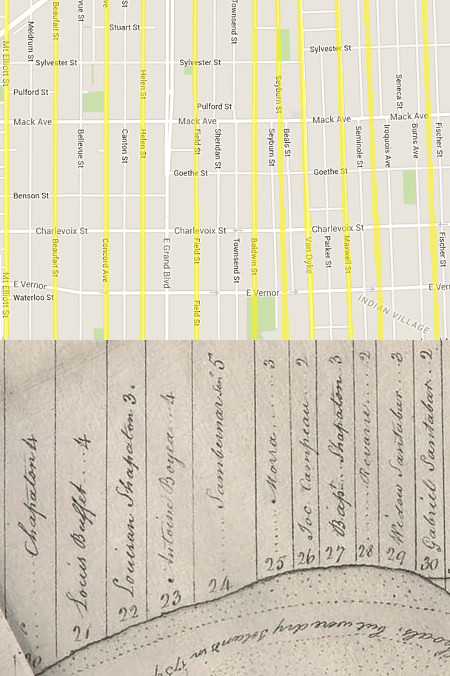

Detail from Aaron Greeley's Map of Private Claims on

Lake St. Clair, the Detroit River and Lake Erie, 1810.

Image sourtesy Seeking Michigan. (Source.)

A distinguishing feature of early Detroit and other French settlements in North America is the way farmland was divided into long, narrow strips commonly referred to as ribbon farms. In Metropolitan Detroit, these farms were established on both sides of the Detroit, Rouge, and Clinton Rivers, as well as on Conner's Creek and the shores of Lake St. Clair. They are found elsewhere in Michigan, in Monroe, Saint Clair, Cheboygan, Mackinac and Chippewa Counties.

Dividing riverfront and lakeshore land in this way had two important advantages. First, it provided access to the water, the primary mode of transportation, to the maximum number of families. Second, it placed each farmhouse at a minimum distance from one another and from the fort at the center of the settlement. Visitors to early Detroit noted that the continuous row of houses along the river created the impression that the settlement was larger than it really was.

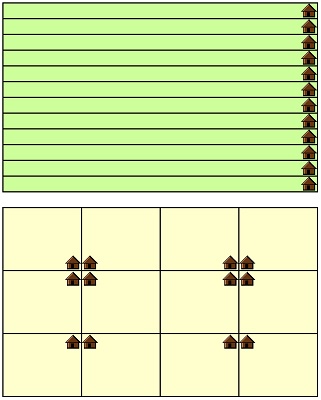

Twelve farms of equal area, each containing one house,

divided into ribbon farms (top) and into a simple grid (bottom).

A typical farm in early Detroit contained a house close to the water, and a road between the house and the shore. Orchards of pear, apple and cherry trees were characteristic of the old French farms, grown either in front of or behind the farmhouse. "Almost every farmer had from one to half a dozen" pear trees, wrote historian Silas Farmer. Bela Hubbard in the 1880s described old pear trees that had reached up to eighty feet in height.

This house was built ca. 1835 at the foot of the Labrosse Farm, roughly between

Seventh and Eighth Streets in Detroit. To the right are old French pear trees.

Image courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. (Source.)

The main cereal crops grown in the early days were Indian corn, wheat, and oats. Farmers also kept vegetable gardens, raised livestock, and even grew grapes for wine making. Cattle grazed on the farmers' land or on the public land north of the fort. The ribbon farms extended into the dense hardwood forest that surrounded the settlement, but these rear portions of the lots were not cultivated.

Most farms were two or three French arpents wide (1 arpent = 191.831 feet), but some measured five arpents across or more. All farms on the Detroit River were forty arpents deep--about one and a half miles long. The borders between individual farms were marked by ditches.

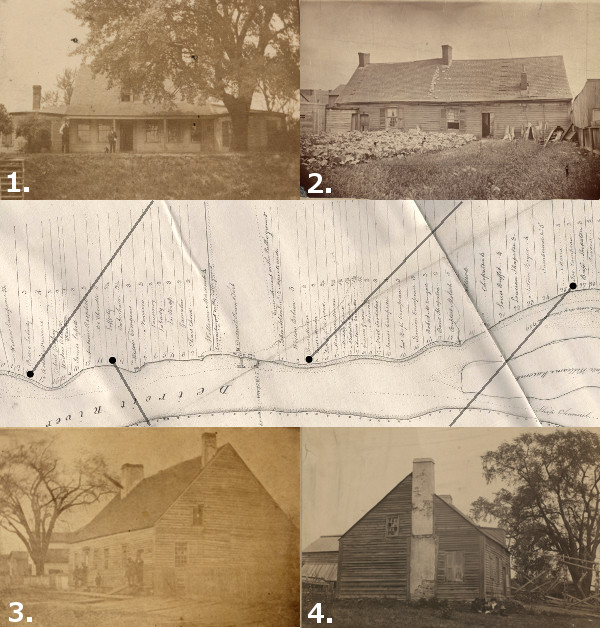

Houses from Detroit's old "ribbon farms."

1. The Labadie House. Built circa 1780, demolished 1910. (Source.)

2. The Moran House. Built circa 1734, demolished 1886. (Source.)

3. The Lafferty House. Built in 1747, burned or demolished 1861. (Source.)

4. The Hamtramck House. Built 1802, demolished 1898. (Source.)

Images courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

Map: Detail from McNiff’s 1796 Plan of the Settlements at Detroit.

Image courtesy Detroit Historical Society. (Source.)

Early Grants

When Antoine de La Mothe Cadillac founded Fort Pontchartrain in 1701, the French Canadian settlers were dependent on trade with Native Americans and supplies from Quebec for food. Although some crops were grown on the public grounds, no farms were granted to white settlers for several years. Cadillac had not yet been authorized to make such concessions, and there was little available land close to the fort, which was flanked on the east and west by Miami and Huron villages, and an Ottawa village farther upstream.

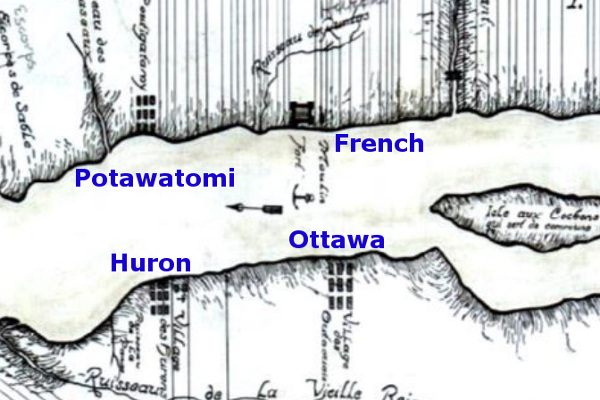

Settlements along the Detroit River, circa 1702.

From south to north: Huron, French, Loups, and Ottawa.

Miamis soon joined the Loups and lived together in the same village.

Image courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

(Source.)

Peace among the First Nations gathered at Detroit was tenuous, and the locations of villages shifted after major conflicts. In just a few years, the Miami had moved to Ohio, and the Ottawa relocated across the Detroit River. By 1707, Cadillac had the authority to grant land concessions, and the first farms allotted were east of the fort, on the land left vacant by the Miami and Ottawa.

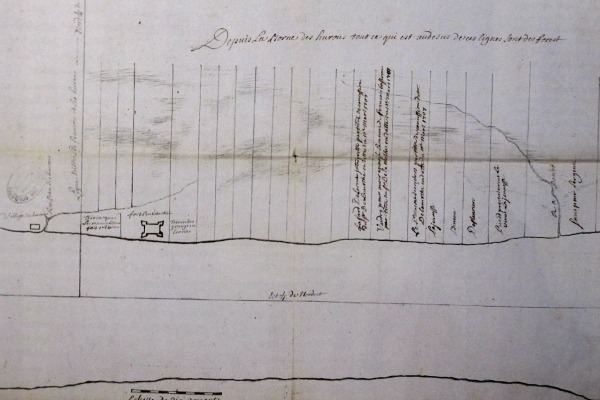

Plan of Detroit in 1731 by Henri-Louis Deschamps de Boishébert,

probably the earliest depiction of Detroit's ribbon farms.

Image courtesy Wayne State University Press. (Source.)

Researchers have identified the recipients of thirty-one farm grants (PDF) made by Cadillac between 1707-1710. These "grants" came laden with multiple obligations and restrictions. Each owner was required to:

- Pay Cadillac annual dues of five livres

- Pay an annual fee of ten livres for the right to trade

- Refrain from hunting hares, rabbits, partridges or pheasants (other hunting was allowed)

- Grind all grain at Cadillac's mill and pay the associated fees

- Begin improvements on land within three months

- Obtain Cadillac's permission to sell land, and Cadillac had first right to buy

- Provide timber for the stockade or shipbuilding if requested

- Not work as blacksmith, cutler, armorer or brewer without a permit

- Not sell liquor to Native Americans

- Plant a maypole before the door of Cadillac's home each spring (!)

Cadillac was forced to leave Detroit in 1711, having been "promoted" to the office of Governor of Louisiana. Few if any grants were made for twenty years while the colony languished.

French Growth and British Occupation

King Louis XV, eager to see Detroit become self sufficient, pressured its commandants to continue leasing farmland in the 1720s and 1730s. In the relative peace that came with the end of the bloody Fox Wars (1712-1733), additional land grants were made between 1734 and 1736. Farmers began to build houses on their land around this time.

A dispute between the Huron and Ottawa in 1738 led to the Hurons' abandonment of their village west of the fort. The French divided the former Huron settlement into more ribbon farms in the 1740s, expanding the colony downstream until it met the border of the land owned by the Potawatomi, whose village was located at what is now Riverside Park, near the Ambassador Bridge. The Hurons were eventually enticed to return to Detroit, settling across the river from their former village.

Detroit in 1749. (Source.)

France redoubled its efforts to expand the colony in 1749, promising new settlers not just land, but tools, animals and seed. Twenty French Canadian families arrived that year, establishing ribbon farms downstream from the fort on what is now the Canadian shore.

Following the takeover of Detroit by the British in 1760 and Pontiac's unsuccessful siege of the fort three years later, the remaining First Nations at Detroit began to sell and abandon their land. Whites who purchased this land divided it into the same ribbon pattern as the generations before them. It was during this period that Belle Isle was purchased from the Chippewa and Ottawa nations, and Grosse Ile from the Potawatomi. Ribbon farms spread both north along the western shore of Lake St. Clair and up the Clinton River, and south along the Detroit River to Lake Erie, moving inland along the Rouge River and the River Raisin.

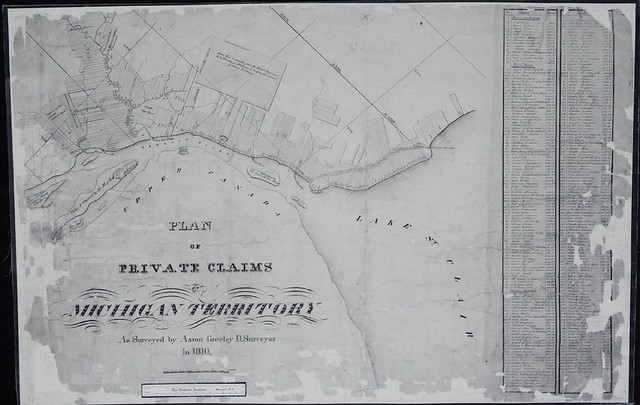

The Private Claims

Click here for a larger version of this image.

What happens to private property when a brand new government takes over a 100 year old settlement with poor record keeping? That was the situation the United States government found itself in when Colonel J. F. Hamtramck took command of Detroit on July 11, 1796. Congress directed the creation of a Detroit land office in 1804 in part to register land claims, but there was only enough documentation to support eight titles.

The process was greatly simplified when Congress passed a law on March 3, 1807 ensuring that residents who had "settled, occupied and improved" land in the Detroit district "prior to and on the first day of July, 1796" would have their claim "granted, and such occupant or occupants shall be confirmed in the title to the same." In other words, if you had a house and/or farm on a parcel of land before July 1, 1796, the U.S. Government would recognize your ownership and issue you a deed. (No Native Americans could file claims because the 1795 Treaty of Greenville extinguished all Indian title to land within six miles of the Detroit River and the west end of Lake Erie.)

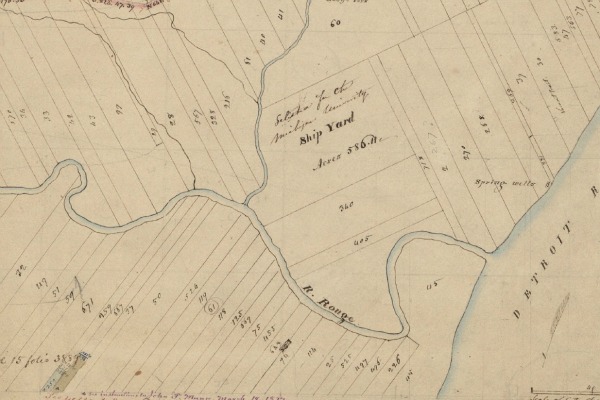

Ribbon farms along the Rouge and Detroit Rivers in 1817.

Image courtesy Bureau of Land Management. (Source.)

Residents filed their applications at the Detroit land office and brought forth witnesses--usually neighbors--who corroborated their claims. Petitions were numbered in the order in which they were received, and the land was surveyed at the government's expense. When an application was approved, the property owner received a land patent. These were originally issued by the Treasury Department, then later by the General Land Office and signed by the President of the United States (at least until the 1830s). The application number was then designated as that parcel's Private Claim Number. Every ribbon farm has a Private Claim Number.

For example, the very first application processed by the Detroit land office was that of Elijah Brush, who happened to claim ownership of the first ribbon farm east of the fort. Upon approval, the Brush Farm was designated "Private Claim No. 1," and Mr. Brush was issued a land patent by the United States Treasury Department.

Private Claims on the Clinton River in what is now Harrison Township.

The numbers designate each parcel's Private Claim Number.

Detail from Aaron Greeley's Map of Private Claims on

Lake St. Clair, the Detroit River and Lake Erie, 1810.

Image sourtesy Seeking Michigan. (Source.)

Although the original French grants only extended inland by 40 arpents (about one and a half miles), a modern map of the Private Claims in Detroit shows them being twice that length. The reason for this is that the farmers on the U.S. side of the Detroit River petitioned Congress in 1807, pleading for extensions to their claims. They argued that these forested back lots were their only source of wood for fuel and for the construction of fences and buildings. Congress passed a law in 1812 allowing these landowners to claim a full 80 arpents in depth, as long as the land behind their original 40 arpents was unoccupied and unclaimed. The Private Claims recognized today extend almost three miles inland, but the French Canadian farmers of eighteenth century Detroit never occupied lots of this size.

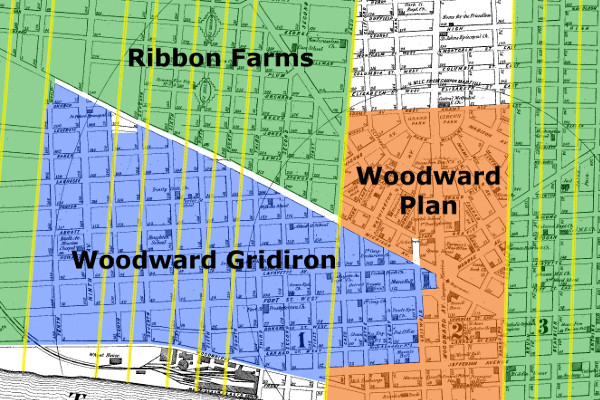

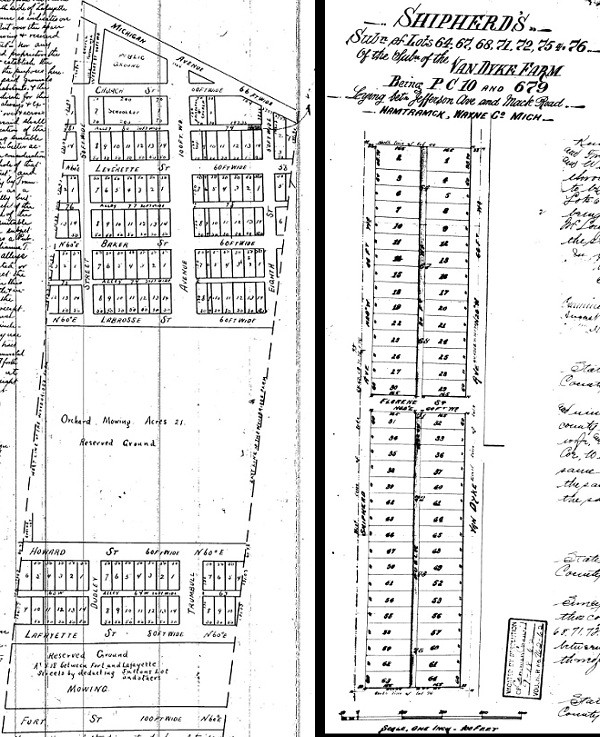

Subdivisions

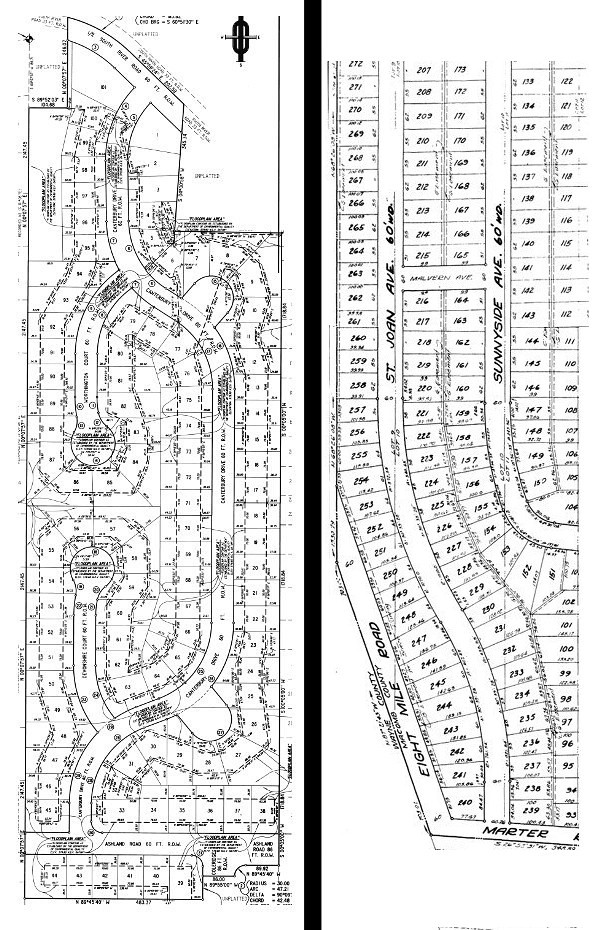

Detroit enjoyed a rapid expansion following the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, enticing the owners of the ribbon farms to turn their land over to urbanization. Former fields, orchards and meadows were subdivided into building lots, streets and alleys. Augustus Woodward's famous street plan was abandoned before any of the ribbon farms were incorporated into the city. A simpler plan of rectangular city blocks aligned with Woodward and Jefferson Avenues was followed for a time on the city's near west side, and portions of some ribbon farms were subdivided in accordance with it. This gridiron pattern disregarded the boundaries of the ribbon farms, resulting in a multitude of fractional lots. This system was also dropped, and farms were then subdivided on an individual basis. From then on, the boundaries of streets and building lots would conform to the outlines and positions of the old French land claims.

Ribbon farms dictated the orientation of most of Detroit's streets within three

miles of the river. Borders of the farms are highlighted in yellow. The base map

is from 1872, long before urban renewal destroyed the street grid. (Source).

A farm owner who wanted to subdivide their land was required to submit to the county a plat indicating the outlines and dimensions of lots, streets and alleys. When approved, streets and alleys became public property, and the proprietor was the owner of the individual lots, which could be sold as they saw fit. Farmers near Detroit tended to subdivide their land in sections rather than all at once.

Left: Subdivision plat of part of the Woodbridge Farm in Corktown, 1858. Blocks are aligned with the "Woodward Gridiron" rather than the farm's borders. The area between Howard and Labrosse Streets was still an orchard and not yet divided into lots. (Source.)

Right: Subdivision plat of part of the Van Dyke Farm in West Village, 1890, in line with the farm's borders. Florene Street has since been renamed St. Paul Street. (Source.)

Private Claims in the suburbs were subdivided well into the 20th century, as the following two examples show.

Left: River Bend Subdivision No. 1 (1999), part of Private Claim No. 207 in Harrison Township. (Source.)Disparity among the widths of Detroit's ribbon farms created a lack of uniformity in the city's street grid. The French grants normally ranged anywhere from two to five arpents wide, resulting in irregular city blocks when developed. The image below shows an example on Detroit's east side. The lower half is from a 1796 map, indicating the widths of farms in arpents above each owners' name. The upper half is a modern map of the adjacent area. Ribbon farm borders are highlighted in yellow.

Right: Edward Rose Subdivision (1952), part of Private Claim No. 656 in St. Clair Shores. (Source.)

Old map: Detail from McNiff’s 1796 Plan of the Settlements at Detroit.

Image courtesy Detroit Historical Society. (Source.)

As with Native American trails, the French ribbon farms have imprinted the landscape in ways that survive long after their makers have left. The history they have made here is still very much alive and with us today.

Click and hold the white divider in the images below and slide left and right to compare old maps with satellite views and to see how ribbon farms influenced urbanization and suburban sprawl in Metro Detroit.

Private Claims in what is now Grosse Pointe Woods and Grosse Pointe Shores.

Old map: detail from J. Fletcher's 1817 survey of township I south range XII east.

The rear border of Private Claims No. 317 & 318, ribbon farms on the Rouge

River, create this anomaly on the Detroit-Dearborn border, shown here in red.

Old map: detail from J. Fletcher's 1817 survey of township II south range X east.

Ribbon farms in what is now St. Clair Shores.

Old map: detail from an 1875 atlas of Macomb County. (Source.)

The City of Harper Woods lies on the extensions of ribbon farms on Lake St. Clair.

Old map: detail from an 1876 atlas of Wayne County. (Source.)

Your work is outstanding and makes history come alive. This is a project that I have worked on searching for ancestors and where they lived. The depth of your research supports every detail that you write about regarding the farms. The method of displaying the information visually offers much to help understand how important the French Ribbon Farms are to Michigan. The early French settlers had to adjust to change as they lived under different political regimens...and this research on your blog provides a tribute to how the French shaped the environment of Detroit today. They are not ghosts of the past, their efforts with creating a place to inhabit as people, live today as reminders within the street names and gridwork of the river region. Thank you for writing about this subject RMIller ( descendant of Joseph Beaubien)

ReplyDeleteWhat a great post! I really enjoyed the history, and the juxtaposing of the old maps with the new ones was very cool! The ribbon farms in Detroit have always interested me, and this was most informative.

ReplyDeleteTerrific research on our ribbon farms and the relation to current streets. This was never so clearly illustrated as you just provided!

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing your knowledge. I learned a lot reading and viewing the images. I too likes all the maps especially the slick ones that you slide over. ( descendent of Jacques Campau )

ReplyDeleteThis is Fascinating! Always wondered about the extent of the Ribbon Farms. Sad that those four Eighteenth Century homes were taken down. Not everything is salvageable but nothing from that era remans1

ReplyDeleteSo interesting! Thank you for doing this. My grandmother's family were the Salters and it is very cool seeing their farm plot in the maps of early Harper Woods.

ReplyDeleteThis is just extraordinary! It's like history that has come to life.

ReplyDeleteDescendants of marsac ribbon farm

ReplyDeleteWOOHH!!! Amazing blog. Thank you for this interesting information provided. I'm looking for some more stuff.

ReplyDeleteWalnut Farmlands Sale

My family moved into an old Victorian farm house built in the mid 1800's. At addressed at 1086 McKinstry St, at the Western edge ot the 'Hubbard Farms Dustrict'. Purchased from the estate of the last member of the original family living. Full of the accumulation of furnishings, household goods and memories of their generations in the home. A time capsule from the early days of Detroits and it's 'Ribbon Farms'.

ReplyDeleteThank you for this article

I felt very happy while reading this site. This was really very informative site for me. I really liked it. This was really a cordial post. Thanks a lot!

ReplyDeleteFarmlands for Sale Turkey

Farmlands Investment Turkey

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteHELLO. I SEE THAT YOU ARE WELL ORIENTED IN THE HISTORY OF FRENCH DETROIT, SO I WOULD BE GRATEFUL IF YOU ANSWER A FEW QUESTIONS.

ReplyDeleteDURING THE SPEECH IN FORT DUQUESNE IN 1757, PONTIAC ASSUMED FROM THE STROGING OF M. APPROXIMATELY, NICHOLAS ORONTONY DIDN'T HAVE ONE HAND, YOU MAY KNOW IN WHICH CIRCUMSTANCES I LOST. WHEN DID HE LOSE HER AND WHICH HAND WAS IT?

Supposedly, PONTIAC, AT THE HEAD OF THE FRENCH AND THE INDIAN NEIGHBORHOOD, PASSED MIKINAC (ZOLWIA) FROM DETROIT IN 1746. HOW DO YOU THINK HOW MUCH WAS TRUTH IN THIS? WHEN I SETTLING UNDER DETROIT DID MIKINAC LIVE IN THE SAME VILLAGE AS THE KINOUSAKI WATER AND PONTIAC HAVE A SEPARATE CAMP?

WHO WAS THE DETROIT COMMANDANT IN 1748-50?

Supposedly, Pontiac lived on the outskirts of his village, and other sources say that he lived on one of the nearby islands, how was it really?

WAS PONTIAC AN OFFICER OF THE FRENCH ARMY?

IF YES, WHAT KIND HAS THERE AND WHEN WAS IT?

DO YOU KNOW BY THE NAME OF ONE LEADER OR WARRIOR OF A POTTAWATOM WHO WORLD IN THE BATTLE OF MONONGAHEL?